A raider's life

Can you handle chickens? Yes, said Pat, and became one of the Animal Liberation Front’s raiders. It was exhilarating, but the police got closer and closer

It was a shock to see him standing there, shotgun in hand. It was a greater shock when he started shooting at us. I knew that I had to be somewhere else pretty damn quick, even if it meant scaling a wall that would । have been impossibly high if we weren’t being shot at.

For a moment I questioned what I was doing in someone else’s farmyard at three o’clock in the morning, equipped to cause criminal damage. But not for long. I have always taken things to the limit and there hasn’t been much in my life that can equal the exhilaration I felt while ALFing. I disposed of the black clothes and boltcutters—which we did on every raid—and got the hell out of the area.

This raid came early in the five years that I spent in the Animal Liberation Front. The process which led me to join ALF began when, as a 12 year old, I witnessed a calf collapse on to its knees in terror as it was led to slaughter at the local abattoir. I ran home in tears. Around four years later I saw a poster of a monkey with electrodes hanging out of its head. I found out who’d put it up and he asked me to join the local hunt saboteurs. I began sabotaging hunts and got into pretty small-scale stuff like gluing fur-shop locks.

Then, of course, there was the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection demonstration at Porton Down (the government chemical warfare establishment), where I discovered that ordinary people can exercise considerable power.

The demo began peacefully, but on this occasion we were no longer prepared to march ten miles just to stand outside and sing. Punks started pulling at the perimeter fences, which gave way surprisingly easily. The police on the other side ran—this was going to be our day! We tore through about six layered fences as the demonstration developed its own momentum. At the final fence, I knew this was as far as we were going to go. It wasn’t just the infrared beam on my heart from a government sniper’s rifle; it would have been mad to expose ourselves to germ and chemical warfare, which, for us, unlike animals, is not a daily reality.

So I was ready to join when I was approached on a sab by the ALF. Their first question was, “Can you handle chickens?”—because, I learnt, many people have a phobia about birds and feathers. Battery chickens are especially disgusting: slimey to the touch, with sores and scarcely any feathers. Several new recruits were tested on my first raid; most of them went to pieces. Its purpose was publicity and we were accompanied by a journalist from the Sunday Mirror. (The newspapers were sympathetic to animal liberation then. They were later frightened off by the economic damage we did.)

As with my later raids, I was as nervous as hell as we drove to the farm, but once we got there it was quite surreal. I just

did what I had to do and wasn’t nervous again until we were making our getaway. The battery farm was ramshackle. I will always remember the disgusting stench and a plank of wood nailed across the opening hatches of the chicken cages. These chickens were permanently incarcerated. But there were holes in the top of the cages to allow farm-hands to remove the dead.

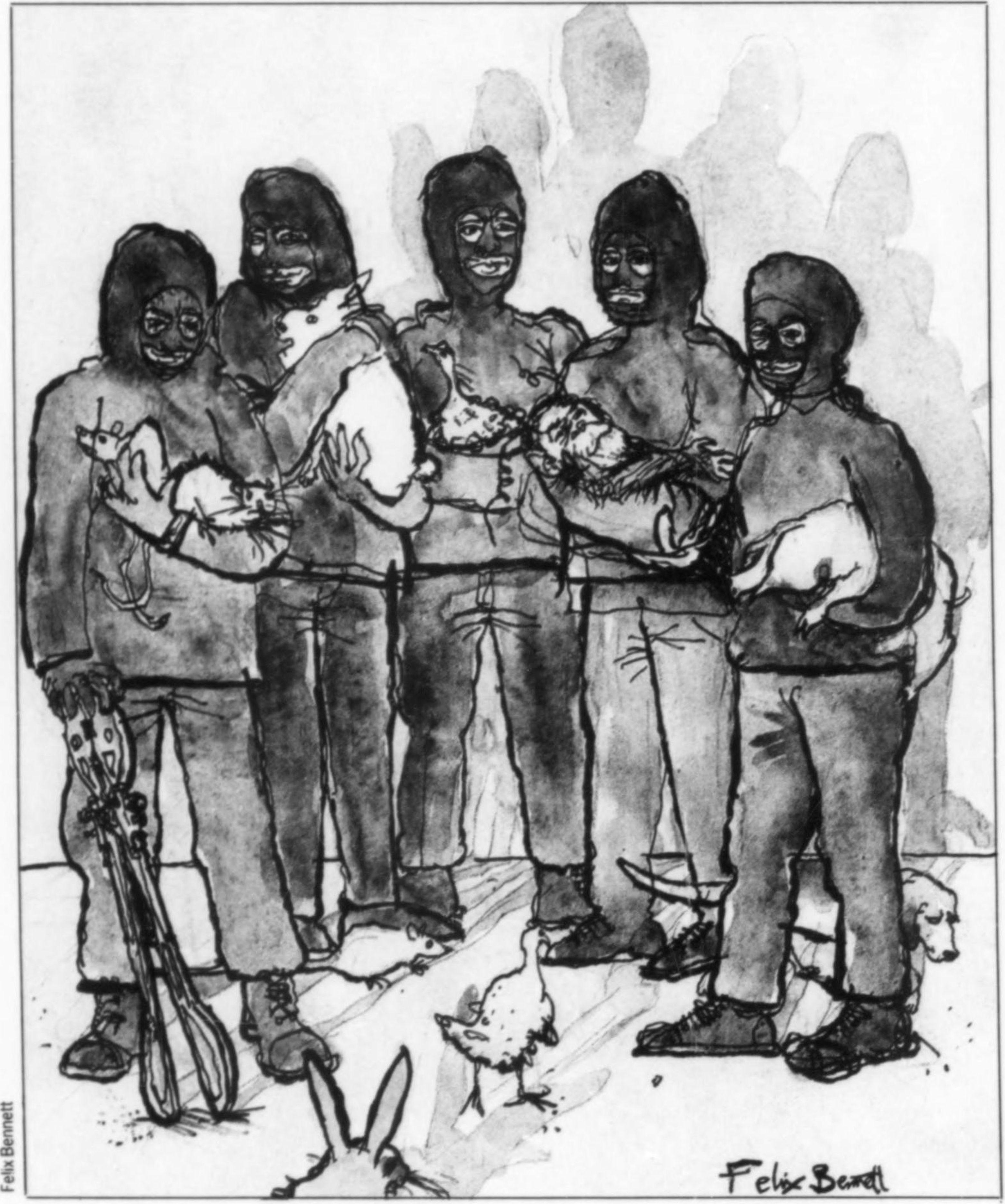

We liberated about 30 chickens on this raid. The only real danger came when we were asked to pose for photographs in the forecourt of the nearest service station, wearing balaclavas and holding the chickens and boltcutters under our arms. After which we left to relocate the liberated chickens on a free-range farm. I didn’t like running unnecessary risks and decided to form my own ceil.

Another publicity raid that I went on came when a highly toxic section of Porton Down was transferred to the densely populated area of Colindale in north London. The authorities claimed that security was adequate and the local people had nothing to fear. Yet in 15 minutes we had cut through the perimeter fence, sprayed “ALF has been here” on an outside wall, and left without being noticed. The disturbing thing was that, before we left, we pushed at a window that began to give way, which meant that anyone could have entered the place and perhaps spilled a canister that could have wiped out the population of London. The authorities denied that we had penetrated their plant. That is general policy on ALF raids. The police always advise people to deny that anything has happened, presumably to starve the ALF of the “oxygen of publicity”.

It was problems with publicity that led me to the conclusion that the best way of fighting for animal rights was through economic damage and putting the bastards out of business. I’ve always been a perfectionist and really enjoy a job well done. I remember one raid on a battery farm that gave me immense pleasure. The farm had been cleared of chickens while a new electronic feeding mechanism was being installed. We chopped up the wiring and cut huge holes in the cages.

On the way out I spotted a brand-new lorry. It was too good a target to be missed. As everyone but my driver left, I siphoned some petrol from the tank into a milk bottle. I then cut the air-brake cables and threw the lighted petrol into the cab. Blue flames from the ignited compressed oxygen danced around the cab. I stood mesmerised until I was blown backwards by the exploding lorry. I lay on the ground laughing, then ran like hell.

We were offered cigars on our return to the ALF offices after this raid. They’d been sent by a woman who supported the ALF with the message, “Give these to the lads after a raid.

Ours was an all-woman group and not one of us smoked cigars. The incident illustrates one of the misconceptions that people hold about the ALF—they assume that we’re all young blokes who steam carelessly into farms. But the majority of people I worked with were women, sometimes elderly.

Quite a few of us were professionals, like a doctor and nurse who came on a raid on a fur farm where we knew that there was a pregnant woman. We planned all our raids carefully and cased every farm or laboratory for at least a week in advance. We had, for example, electricians who took out security systems for us.

The raids on scientific laboratories were always distressing. It was rarely possible to liberate the animals; all we could do was to put them out of their misery. I remember a raid on a lab at Colchester University where I saw mice with lumps on their backs as large as their heads. They were writhing in agony. Some animal liberationists believe that we should never kill the animals—it’s playing God, they argue, but I had no qualms about injecting the mice with barbiturates.

In another lab I saw a sheep chained in a bath of sheep dip. Its eyes were caked together with the liquid and large flakes of skin were falling from its body. I met beagles which ran away from me because they assumed that all humans were going to harm them. I had to turn away from a monkey, beseeching me for help with its arms stretched out from its cage. How far would I get running down the high street with a monkey under my arm?

You just have to ignore the pain and persist with your purpose. It is necessary to establish what they are researching behind closed doors and to pass the information on to legal pressure groups which can then bring it into the public eye. You can do a lot of economic damage just by publicising what is going on. No cosmetic firm wants the publicity of having its products associated with blinding or abusing animals these days.

I chose to join the ALF as it was the cutting edge of the animal rights campaign. Any liberation movement needs to work across a broad spectrum, which covers both legal pressure-group activity and direct action. Without the ALF’s raids the movement would have grown stagnant. How many people would have been aware of the horrors concealed in battery farms, laboratories and other plants without the direct intervention of the ALF?

I finally left the ALF when I decided that I would be of more use working above ground than locked up in prison. As our raids became increasingly effective, the police got a lot better at dealing with us. Scotland Yard set up its own unit to deal with animal rights activists—they described us as “urban terrorists not connected with the IRA”. There was frequently a car outside my house on Saturday mornings. The police began to follow me around the London Underground. I played “spy games” with them, leaping through barriers, jumping on and off trains.

But it had its serious side too. The last raid I went on was planned in parks, and we took our security arrangements to the point of paranoia. Only proven people were chosen to take part. Yet when we did a last-minute reconnaissance on the day of the raid, the place was staked out. Luckily my partner and I were dressed as if we were on a date and the police assumed we were just a courting couple. They asked us to leave the area. I felt that my luck had been exhausted and if I didn’t get out then, I’d soon be living at Her Majesty’s pleasure.

But I was also influenced by the emergence of groups like the Animal Rights Militia, which regard people as legitimate targets. I still believe in direct action, but attacks on people are not only unproductive, but impossible to justify. I subscribe to the principle, widespread in the animals rights movement, that no human being or animal should be harmed on a raid. We always took enough people on raids, for example, to make sure we could restrain guards without hurting them.

The British people regard themselves as animal lovers, but every day in this society animals are abused and slaughtered. Glossy advertisements disguise and even glamorise what’s being done. This probably explains why they are always shocked when we confront them with battery chickens and mutilated foxes in shopping centres. The Animal Liberation Front has done much to make the public aware and has cost the exploiters dearly. For me personally it has shown what ordinary people like me can do, once we realise that we possess power and are ready to use it.