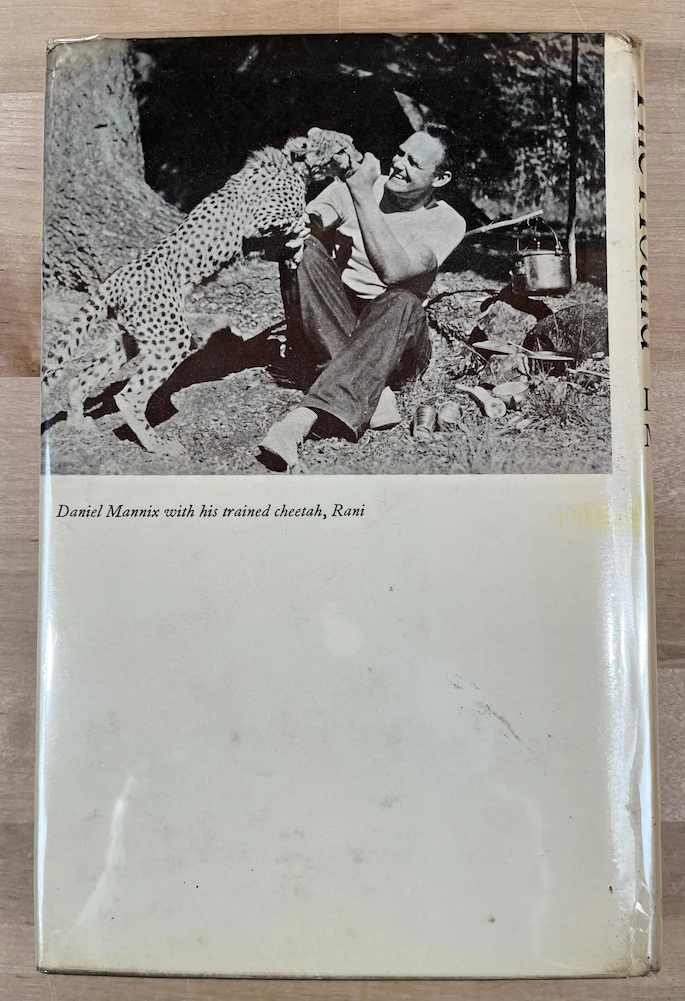

Daniel P. Mannix

The Fox and the Hound

Winner Dutton Animal Book Award 1967

3. The First Hunt - Shooting at a Crossing

4. The Second Hunt - Jug Hunting

7. Fifth Hunt - Formal Hunting

8. Sixth Hunt - The Still Hunt

[Front Matter]

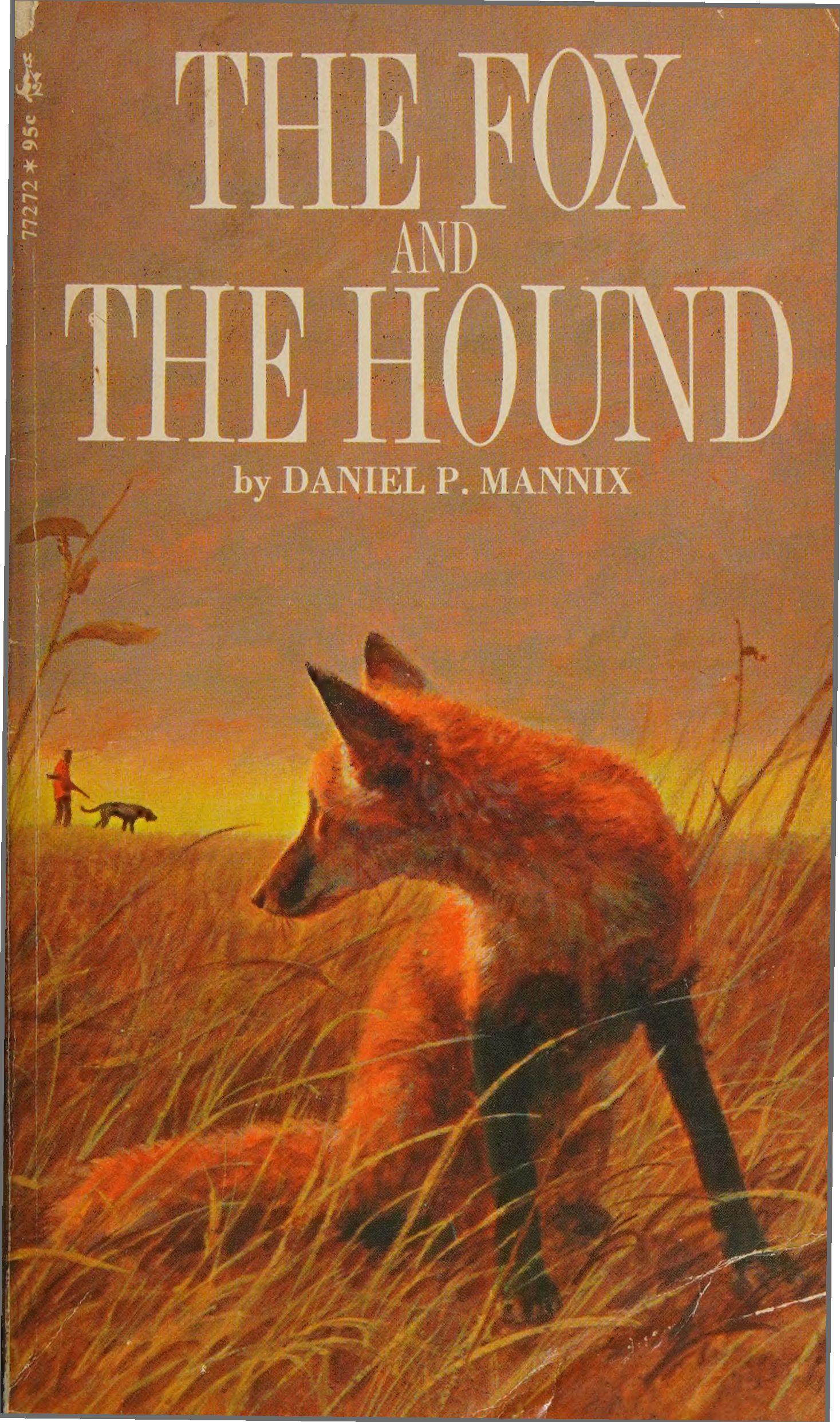

Covers

A CLASSIC DUEL OF NATURE

engages two highly skilled antagonists, each one born and bred to his dangerous calling:

The Fox—welcoming risks, roaming his own range, delighting in his freedom.

The Hound—living for the hunt, devoting his instinct and ingenuity to the service of his master, who longs to bring the red fox to bay.

Packed with incident, suspense, and superb nature writing, The Fox and the Hound is an extraordinary, authentic portrait of animal life. It is the 1967 winner of the Dutton Animal Book Award.

“A masterpiece, it is tops in the field of animal books....” —Omaha World-Her aid

Published by

Pocket Books

Printed In U.S.A.

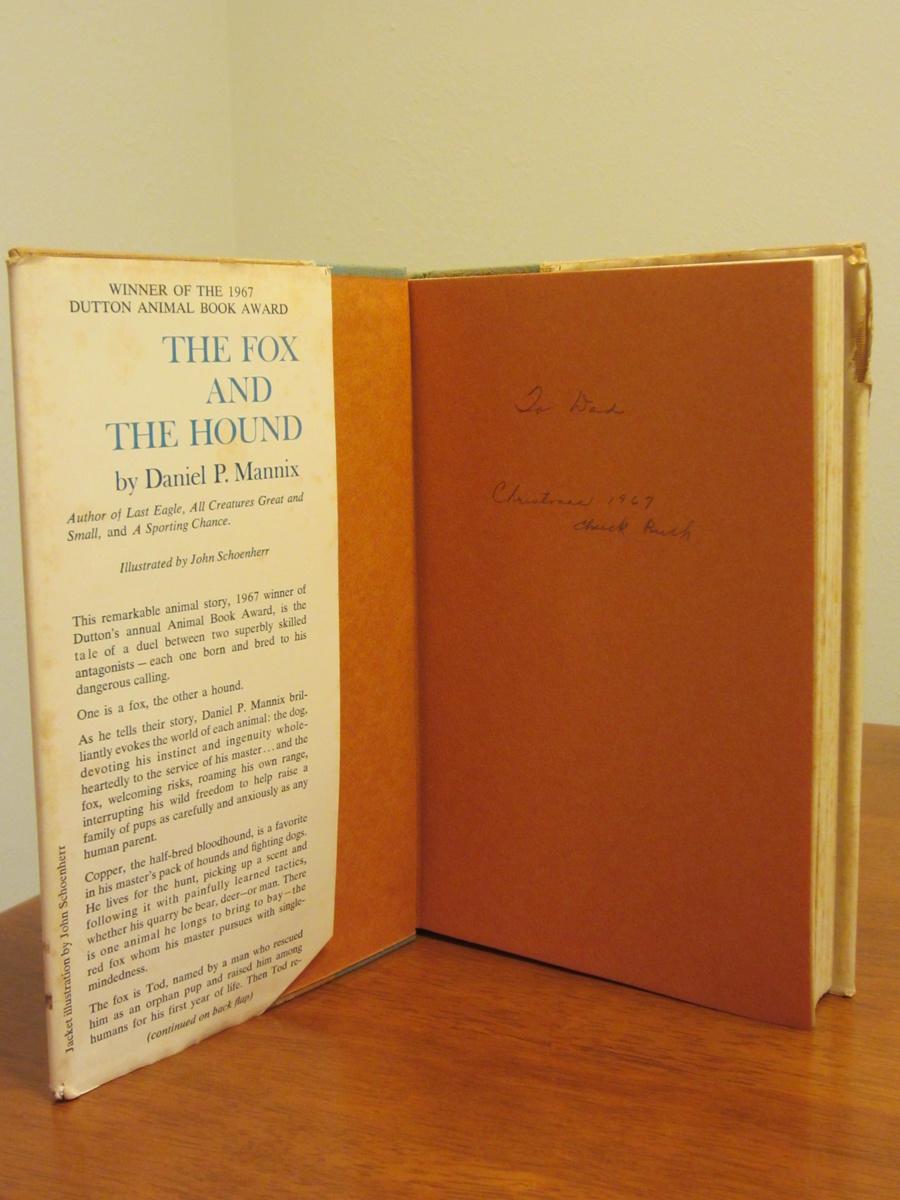

Cover Flaps

WINNER OF THE 1967

DUTTON ANIMAL BOOK AWARD

THE FOX

AND

THE HOUND

by Daniel P. Mannix

Author of Last Eagle, All Creatures Great and Small, and A Sporting Chance.

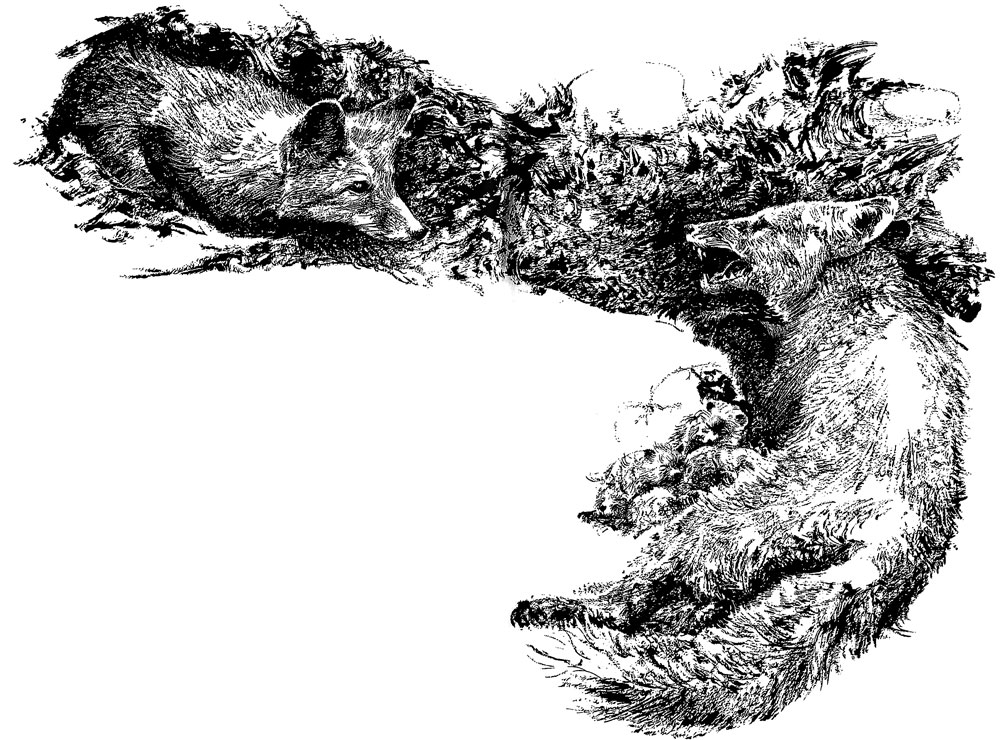

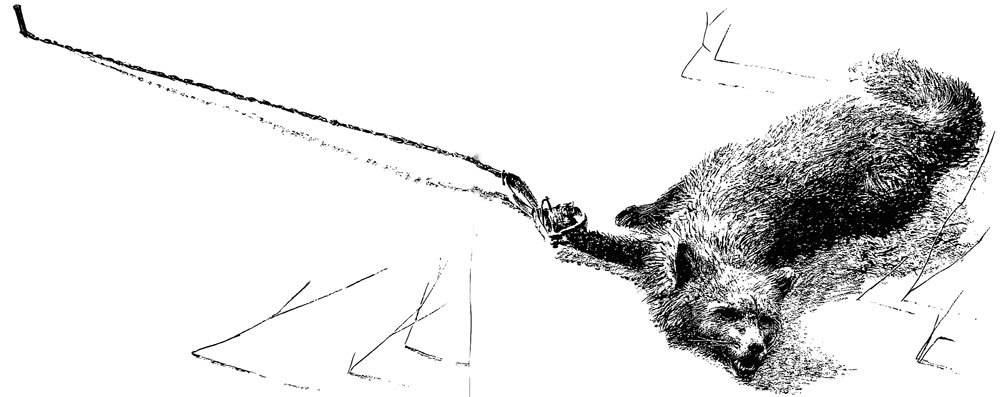

Illustrated by John Schoenherr

This remarkable animal story, 1967 winner of Dutton's annual Animal Book Award, is the tale of a duel between two superbly skilled antagonists — each one born and bred to his dangerous calling.

One is a fox, the other a hound.

As he tells their story, Daniel P. Mannix brilliantly evokes the world of each animal: the dog, devoting his instinct and ingenuity wholeheartedly to the service of his master... and the fox, welcoming risks, roaming his own range, interrupting his wild freedom to help raise a family of pups as carefully and anxiously as any human parent.

Copper, the half-bred bloodhound, is a favorite in his master’s pack of hounds and fighting dogs. He lives for the hunt, picking up a scent and following it with painfully learned tactics, whether his quarry be bear, deer—or man. There is one animal he longs to bring to bay —the red fox whom his master pursues with single- mindedness.

The fox is Tod, named by a man who rescued him as an orphan pup and raised him among humans for his first year of life. Then Tod re-

(continued on back flap)

Jacket illustration by John Schoenherr

(continued from front flap)

turned to the wild. You share the excitement of Tod's strong young life, the thrills of his hunting and mating—discover how he acquires dozens of quick-witted strategies to outwit his constant pursuers. In chapters filled with action and little-known hunting and nature lore, you follow the life-and-death contest of the fox and the hound from their first breathtaking hunt through many memorable encounters to the last hunt of all, with its intensely dramatic ending.

Packed with incident, with suspense, and with superb nature writing. The Fox and the Hound is an extraordinary, authentic portrait of animal life that might well become a classic.

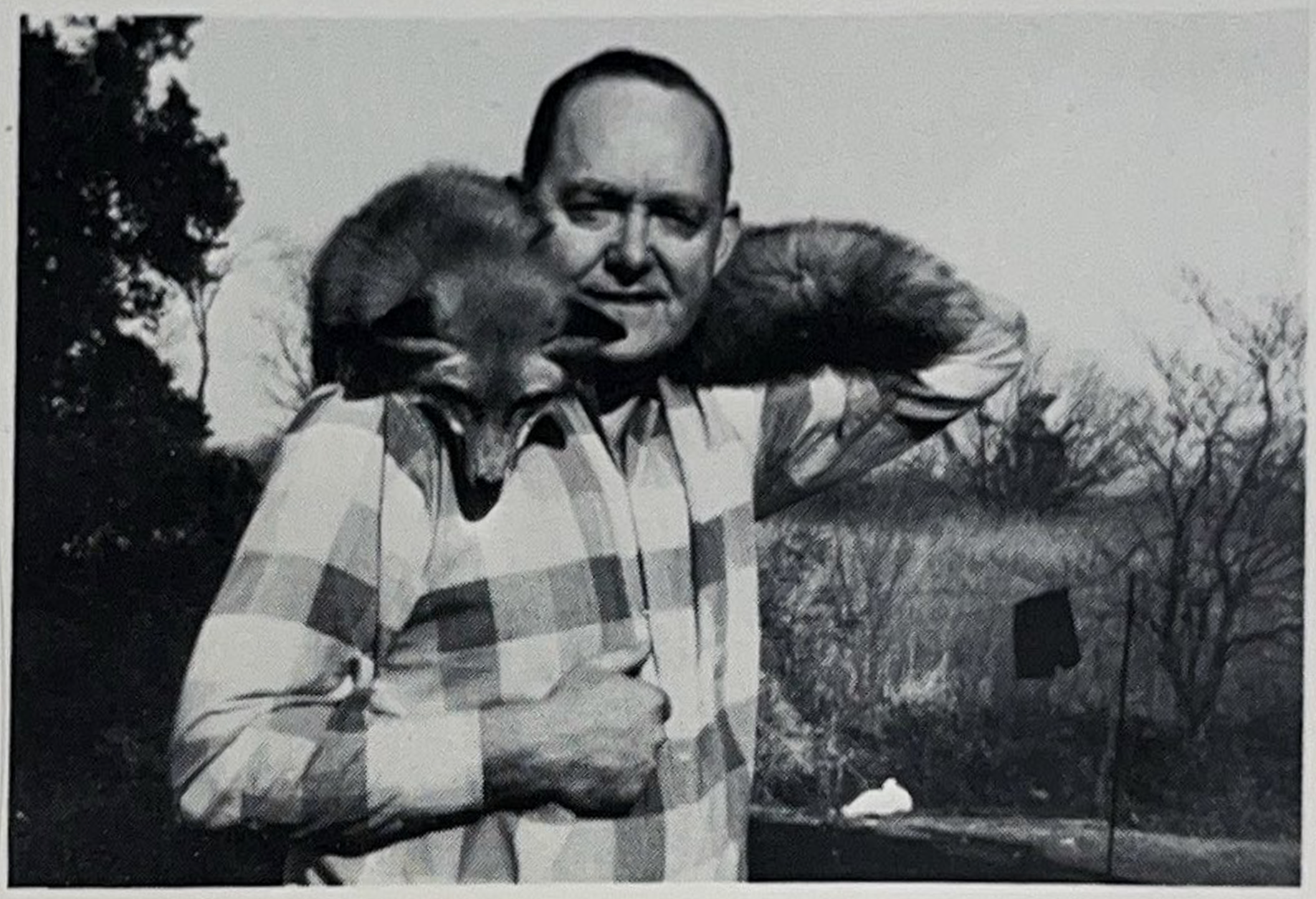

Daniel P. Mannix is one of America’s most knowledgeable and popular authors of animal and nature stories; his books include Last Eagle, and, most recently, A Sporting Chance. Mr. Mannix began collecting animals at the age of five, and he wrote his first book about them while in high school. He lives at Sunnyhill Farm, in Malvern, Pennsylvania, with his wife, two children, and a large collection of animals and birds. His intensive study of the habits and abilities of foxes includes keeping a pair who know him so well that he can turn them loose and watch them hunt, fight, mate and in general live as wild foxes do.

E. P. Dutton & Company Inc.

201 PARK Avenue NEW YORK, N.Y. 10003

[Praise for book]

“A lively and engrossing animal book ...a really exciting story.”

—Associated Press

“This is the 1967 winner of the Dutton Animal Book Award and the worthiest winner since Sterling North’s well-remembered Rascal. If you have any feeling for wildlife, you’ll enjoy this book.”

—Saturday Review Syndicate

“No one who has the slightest interest in animals should miss reading The Fox and the Hound”

—Cleveland Plain Dealer

“A story of a hunt told in a way it seldom is, completely from the viewpoint of the animals.... The hunt goes on, in spurts of activity and by various means, through the long lifetime of the two.... It is wonderful how Mannix has entered so completely into the animals’ way of looking at life.”

—Publisher's Weekly

Other books

A Sporting Chance

Last Eagle

All Creatures Great and Small

Memoirs of a Sword Swallower

Those About to Die

WITH MALCOLM COWLEY

Black Cargoes

WITH JOHN A. HUNTER

Tales of the African Frontier

WITH PETER RYHINER

Wildest Game

FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

The Outcasts

Winner Dutton Animal Book Award 1967

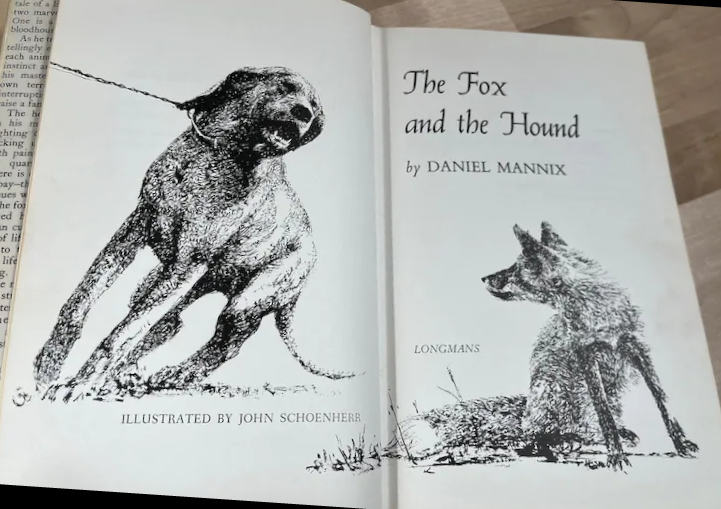

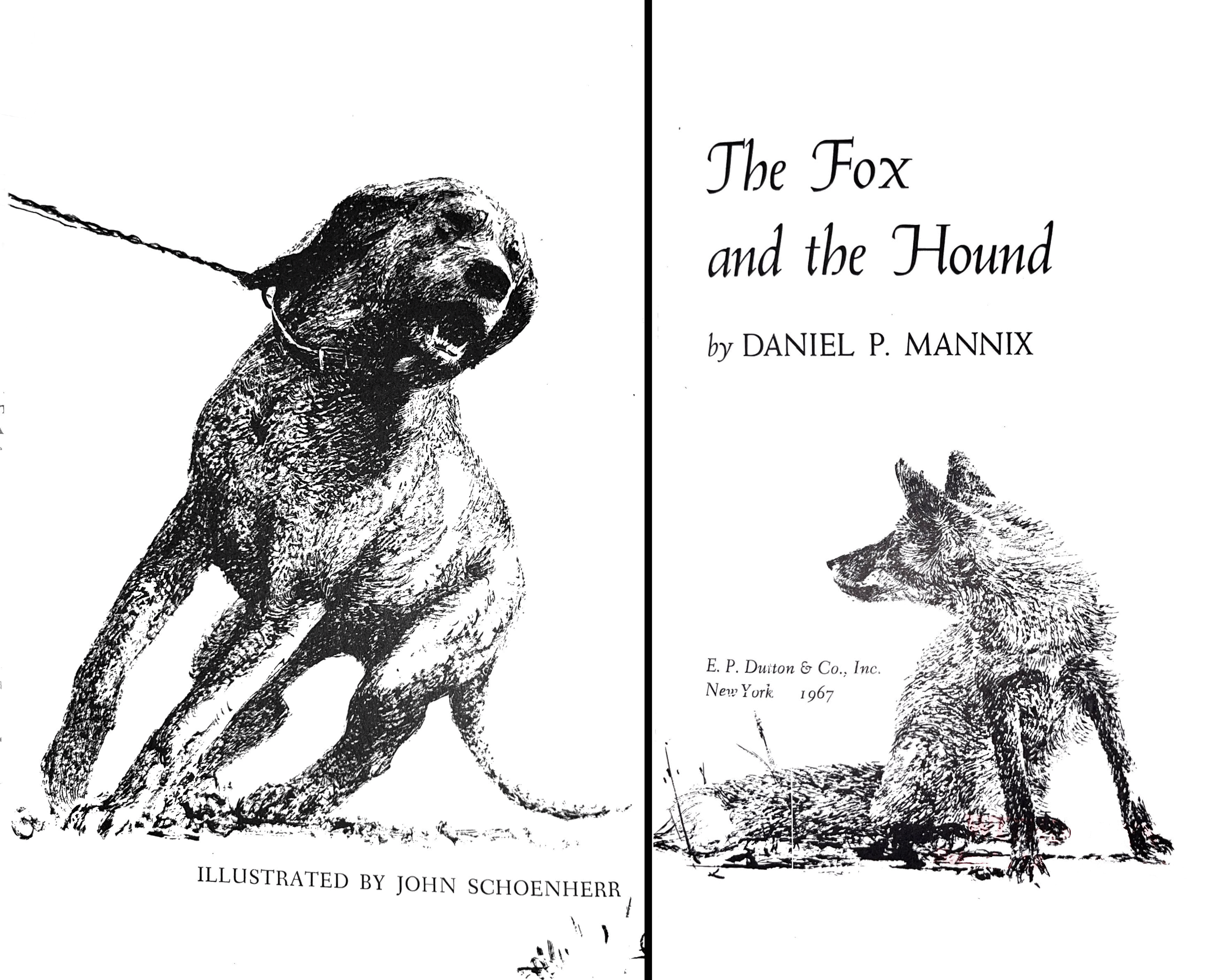

[Title Page]

Illustrated by John Schoenherr

The Fox

and the Hound

by DANIEL P. MANNIX

PUBLISHED BY POCKET BOOKS NEW YORK

First Edition Copyright

First Edition

Copyright © 1967 by Daniel P. Mannix

All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast.

Published simultaneously in the United States by E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., New York, and in Canada by

Clarke, Irwin & Company Limited, Toronto and Vancouver

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 67-20531 Lithographed by The Murray Printing Company

Pocket Books Copyright

E. P. Dutton edition published September, 1967

Pocket Book edition published March, 1971

This Pocket Book edition includes every word contained in the original, higher-priced edition. It is printed from brand-new plates made from completely reset, clear, easy-to-read type. Pocket Book editions are published by Pocket Books, division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., 630 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10020. Trademarks registered in the United States and other countries.

Standard Book Number: 671-77272-3

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 67-20531.

Copyright. ©, 1967, by Daniel P. Mannix. This Pocket Rook edition is published by arrangement with E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc.

Printed In the U.S.A.

[Dedication]

To Jule, my dear wife, in memory of the many times the Tods kept her awake at night fighting or lovemaking

[Contents]

1. The Hound 1

2. The Fox 20

3. The First Hunt—Shooting at a Crossing 43

4. The Second Hunt—Jug Hunting 61

5. Third Hunt—Gassing 86

6. Fourth Hunt—Trapping 106

7. Fifth Hunt—Formal Hunting 127

8. Sixth Hunt—The Still Hunt 143

9. Seventh Hunt—Coursing with Greyhounds 166

10. The Last Hunt 183

Author's Note 195

[Half-title page]

The Fox

and the Hound

1. The Hound

The big half-bred bloodhound lay in his barrel kennel and dreamed he was deer hunting. Of all the quarry he had ever trailed, deer was the hound's favorite, although it was usually strictly forbidden. He had been whipped, beaten with a club, and even hit in the flanks by bird shot for this crime; yet once, after an interminable journey to a faraway place, he had been allowed to track a deer. Now he smelled again that warm, rich odor as he toiled after the quarry. Again he heard the rapid toot - toot - toot of his master's horn blowing the "Gone away," and the notes made him yelp with excitement. He was not running now, but flying over the ground, and the scent was growing stronger, The quarry must be almost in sight. The hound kicked convulsively in his barrel and whined with eagerness.

He was vaguely aware of a distant noise so remote he was barely conscious of it. Yet the noise grew louder and more irritating. It was a shrill Yip-yurr! repeated over and over. The hound tried to banish it from his thoughts and concentrate on the glory of the chase, but the yapping forced itself on him. Gradually the splendor of the hunt began to fade, driven away by that infuriating, sharp yipping. With the noise came penetrating odor that obliterated the glory of the thrilling deer scent. With a cry that was half bark, half growl, the hound came awake. He lay for an instant unsure of what was going on. Then he smelled the pungent scent of fox, and fox very close. At the same moment, the taunting yipping came again.

With a roar of fury, the hound burst from his barrel into the false light of early dawn. There, only a few yards away, a fox was sitting grinning at him. So crazed with rage he could not think, the hound Rung himself at the intruder. The fox did not move. As his jaws were about to close over the stinking red interloper, the hound was flung on his side and lay groveling on the hard-packed earth. He had come to the end of his chain and been jerked backward.

By now every hound in the pack, as well as the fierce mongrel catch dogs, had been awakened and were raging at the ends of their chains. The fox cocked his triangular head to grin at them, knowing he was safe. Then he turned to the hound and barked again in the same teasing way. The taunt set the hound completely out of his head with madness. He flung himself the full length of the chain, rolled on the ground, tore at the metal links, and screamed with frustration while the fox still sat scoffing at him. The fox clearly knew to a foot the length of the chain - no difficult feat, for the fan-shaped strip of padded earth around each kennel showed the boundaries beyond which the captive dog could not go - and was enjoying himself immensely. He had stopped barking, as he could not have been heard above the tumult, and sat gloating over the chaos he was causing.

The headlights of a car swept the hill slope, illuminating briefly the coat of the fox so that it glowed as if with an internal light. Instantly the fox dropped his gloating, confident air. The grin vanished; he crouched down and turned to look at the lane leading to the isolated cabin below him. The lights of a second car glided over him, making the fox crouch even lower. Then as the clamor of the dogs increased in volume and frustration, the fox skulked away, beginning to run as soon as he was clear of the light, and vanished into the scrub-oak thickets.

The hound was the first to stop his frustrated screaming. In spite of the noise of the pack, he recognized the distinctive sound of his Master's car. A few moments later, he was able to identify the second vehicle. It belonged to men who came occasionally to his Master's home, and their presence always meant that his services would be in demand. He could identify half a dozen cars by their sound, although he could not recognize them by sight. When this particular car came, he was always called on to track a man. The hound didn't like tracking men especially - the scent was always poor, and there was no killing at the end of the trail. Although not bloodthirsty like the catch dogs, he did enjoy those last exciting moments of the chase, the anticipated crack of the rifle, and smelling the dead quarry. Still, anything that got him off the tiresome chain was a relief. So he stood hopefully, his tail wagging with doubtful eagerness, as there was still a chance his services might not be required.

He saw the cars stop and men get out. He thought one was his Master; but at that distance he could not be sure. for he was shortsighted. The men went into the cabin and then came out again, starting up the kill. The pack began to bark now, partly in warning and partly in expectation. As the men came closer, the hound could see that the figure in front was his Master. He recognized him by his manner of walking rather than by his appearance. He began to wiggle with excitement.

The Master came up to him and the hound saw that he was putting on a heavy leather belt and carried the long leash that meant man-tracking. He was to go and the rest would be left behind. Frantic with pride and delight, he groveled on the ground, turning his head sideways to expose the jugular vein as a sign of utter abjection to ingratiate himself further with his Master, whom he recognized as a stronger animal. The Master patted him and spoke his name, "Copper," together with other words the hound could not understand but which, from the tone, were gentle. Encouraged, the hound sprang up and, putting his forepaws on the Master's chest, tried to lick his face as he would the face of another dog who had showed friendliness. He was good-naturedly repulsed. The snap of his kennel chain was released and the tracking leash fastened to his collar.

Copper at once started for the cars. He did not throw his full weight on the leash until he heard the click of the snap on the other end of the lead being fitted into the eye socket on the belt. Then he pulled on the leash with all his strength, hurrying the Master toward the cars. There was a young Trigg hound named Chief, an excellent tracker and brave fighter who was the Master's favorite. Copper hated Chief with a hatred surpassing the hatred of a jealous woman. He was mortally afraid the Master might take the Trigg too and wanted to get him away from the other dogs as quickly as possible.

When they reached the cars, Copper hesitated. Sometimes the Master took him in one car and sometimes in the other. The Master spoke to the two men whom Copper recognized primarily by the smell of their leather leggings. He had gone out with them several times before. The Master unclipped the lead, opened the door of his car, and ordered the hound to get in. Copper sprang in promptly, jumping up to his special seat on a rack behind the driver, and lay down, thumping the boards enthusiastically with his tail. There was an apprehensive quality to the thumping, as he still was not absolutely sure that the Master might not go back after that accursed Chief. But the Master climbed in and started the car. As soon as it moved, Copper relaxed and stopped his tail wagging. No doubt now, he was safe.

When they reached the paved highway, the second car passed them. A flashing light appeared on its top and it gave off a moaning wail. Both cars speeded up. Copper would have loved to have been able to lean out the window of the car, drinking in the wind, especially as the car accelerated. The rush of air through his open mouth into his lungs gave him an intoxicating sensation. As this was forbidden, he had to be content with the current of air that came in through the open window. Lying quietly, he sucked it in through his broad wet nostrils. The motion of the car soothed him, and he dozed.

He was awakened by the car turning off the smooth highway and jolting over a dirt track. It was broad daylight. Copper yawned and stretched as well as he could in his cramped quarters. The other car was still ahead of them, throwing up dust that made the hound sneeze. He put one paw over his nose as a shield.

The cars stopped and there was a sound of voices. Copper stood up, tired and cramped by the journey and eager to be let out. The Master opened the door and allowed him to jump down and relieve himself against some bushes. There were a number of men here, all talking, and Copper ran around investigating the new smells and pausing to eat a little saw grass, for the ride had made him slightly nauseated.

Copper heard his Master's angry voice and glanced up, apprehensive that he had done something wrong, but the Master was speaking to one of the men who had come from a cabin with something in his hand. The Master snatched the object and came toward Copper. He held it out and the hound realized it was a scent guide, an object that would give him the scent of the man he was to track.

The object was cloth, and Copper smelled it carefully. There were several human scents, including that of the man who had just handled it and of course the Master's scent. This last didn't bother the hound; he naturally recognized and eliminated that particular odor, but he had no way of telling which of the other scents was the important one.

The Master put the tracking leash on his collar and Copper prepared for work. When he heard the familiar click as the leash was snapped to the belt, he started off. All the men began to follow them, but to Copper's relief the Master shouted and all but one dropped back. He was one of the leather-smelling men, and followed a few feet behind.

The Master took Copper on a long swing around the cabin. The hound worked slowly, sorting out the different scents that came to him. Animal scents, such as rabbit and squirrel, he ignored. Occasionally he crossed patches of wild mustard or mint that gave off an odor that tended to mask other scents. In such cases he skirted the patches to be able to work on uncontaminated ground. Twice he crossed clearings where the hot sun had burned off most of the scent. He worked these carefully to make sure of not missing a faint trail.

At last he hit a clear man track. Copper stopped instantly, sniffing long and loudly. Then he went back to the Master for the scent guide. The Master held it out and Copper sniffed the guide. Yes, one of the odors, and by far the strongest, was the same as that of the track. Without any more hesitation Copper went back to the trail and started out.

It was damp and cool under the trees and the scent held well. Copper forged ahead, at times dragging the Master after him, for the man could not pass under low-hanging boughs as easily as the hound. A few times the hound lost the scent, but by pressing on he was able to pick it up within a few yards. Occasionally, though, the quarry had turned off at an angle at places where the scent had sunk into dry ground or been blown away by a wind. Here Copper was at a loss. The Master had to take him back to the last sure place and start him over. By working slowly and systematically from one wisp of scent to the next, the hound was able to unravel the line. In one especially bad spot he had to dig to find the scent where it had soaked into the ground an inch or so below the surface. In another, the scent had been blown completely away, but Copper found a suggestion of it lodged under the edge of a fallen tree.

They came out on a dirt road. The quarry had sat down to rest - the scent was quite strong - and smoked. But here the trail ended. Copper circled the spot to make sure. Then he lifted one leg and urinated as a sign that the quarry had vanished. As a young hound he had followed trails with so much enthusiasm that he had never had time to relieve himself until the scent ended. Then he had wet. The Master had come to recognize what he meant, so now the act of wetting was a code sign between them.

The Master called to the leather-smelling man who came up. They talked while Copper lay down and rested. It had been a long pull, and he was tired and thirsty.

Finally the Master came over to him. He poured water from a canteen onto the rim of his hat, and Copper drank eagerly. Then the Master washed out his nose and massaged his feet. Finally he shook the leash and said, "Go on, boy. Go find 'em."

Copper looked up reproachfully. He had already indicated that the trail stopped here. Yet the Master was insistent. With an almost audible sigh, the hound rose and checked again. Yes, the scent definitely stopped here. Copper tried to think what to do.

Although there was no scent of the quarry, there was the scent of an automobile, Copper could easily smell the odor of the rubber tires, gasoline, and oil as well as the individualistic metal odor of a machine. As he had to track something, and there was nothing else to track, he began tracking the car.

Following the car was fairly simple, although the hot road hurt his pads. Copper soon found that enough of the scent had blown off the road and clung to the grass along the edge for him to follow it there. The grass was still partly damp and its many blades offered a perfect trap for the scent particles. Even better, the sun was making the scent rise so it floated a few inches above the ground and the hound did not have to drop his head.

After a time he came on the man scent again by the side of the road. It was quite clear, although not fresh. It led into the woods, and Copper started after it eagerly, jerking on the leash. The Master pulled him up and he and the leather-smelling man bent down to look at something. Copper hurried over. They had found a white object that smelled heavily of tobacco but had so little of the man scent that Copper turned away in disgust to get back to the trail. The Master seemed delighted, and from the way he encouraged him, Copper strained forward happily.

Working along the side of a hill, they came on a mass of sharp-edged rocks lying in the full glare of the sun. Here Copper could not find a trace of the trail. He worked up and down the slope, dragging the Master after him, trying desperately to own the line. He did not give his urinating signal, for he knew that here the man had not simply disappeared - the scent had not abruptly ended, but petered out on the hot, bare rocks. It must be here somewhere if he could only find it.

The Master pulled him off the rocks and for the first time since starting out, unsnapped the leash from his collar as a signal he was to stop tracking. Copper lay down thankfully, licking his bleeding pads, for the rocks were sharp. He was still unhappy over the lost line and prepared to try again after a rest.

The men left him and walked slowly across the rocks. They seemed to find something. Painful as it was, Copper limped over to them and hopefully stuck his nose in the place where the Master was pointing. He was ordered back. He continued to sniff, but there was nothing there, and after a second curt command he returned to the soft earth.

The men climbed the rockslide, stopping frequently, while Copper watched them in agony. He could not understand how they could smell the line when he could not. At the top of the slope, the Master called him. To avoid the rocks, Copper loped around the slide and joined the men. The tracking leash was snapped into his collar, and the Master repeated, "Go on, boy. Go find 'em."

Copper cast around and, sure enough, there was the scent again. How the Master had found it he could not imagine, nor did he try. Human beings had strange powers no dog could understand. Trained never to give tongue while following a man, he could not suppress an eager whine. Then they were off again, the big hound pulling on the leash until the Master cursed him, but Copper was too excited at hitting the line again to pay any attention.

The scent was gradually growing stronger now. It was not too old. As Copper was forging ahead, he was abruptly pulled up short. The men were looking upward. Copper glanced up but could see nothing. The men talked in low voices, and then the Master ordered him on again.

The scent was good now. The eager hound forced his way through laurel tangle and greenbrier so thick the men could hardly follow. They reached a gully in the woods, and Copper smelled water at the bottom. He started down; but the scent was very bad indeed, for there was no circulation of air in the shielded gully to lift the scent above the ground, and Copper was forced to keep his nose almost in direct contact with the earth.

He had raised his head to blow dust from his nose, when suddenly he stopped dead. Ignoring the trail, the hound care- fully tested the air. Yes, there it was. The man close - so close the hound could air-scent him. At the same instant, the hound knew the quarry was dead, The heavy, sweet-sick smell of death was strong. There was also blood.

Paying no attention to the trail now, the hound plunged down the steep bank, the men sliding after him on their buttocks. At the bottom of the gully ran a clear stream. Thirsty as he was, the hound did not stop to drink. He splashed through the water and up the opposite bank, the men cupping up quick handfuls of water as they followed. As they climbed, a frenzied rustling came from the bushes ahead. Half a dozen black shapes flushed, and beat their way upward on huge, sooty black wings, leaving a carrion reek as they rose. Copper ignored them. He strained forward, took one strong sniff, and then sat down. The quarry was here.

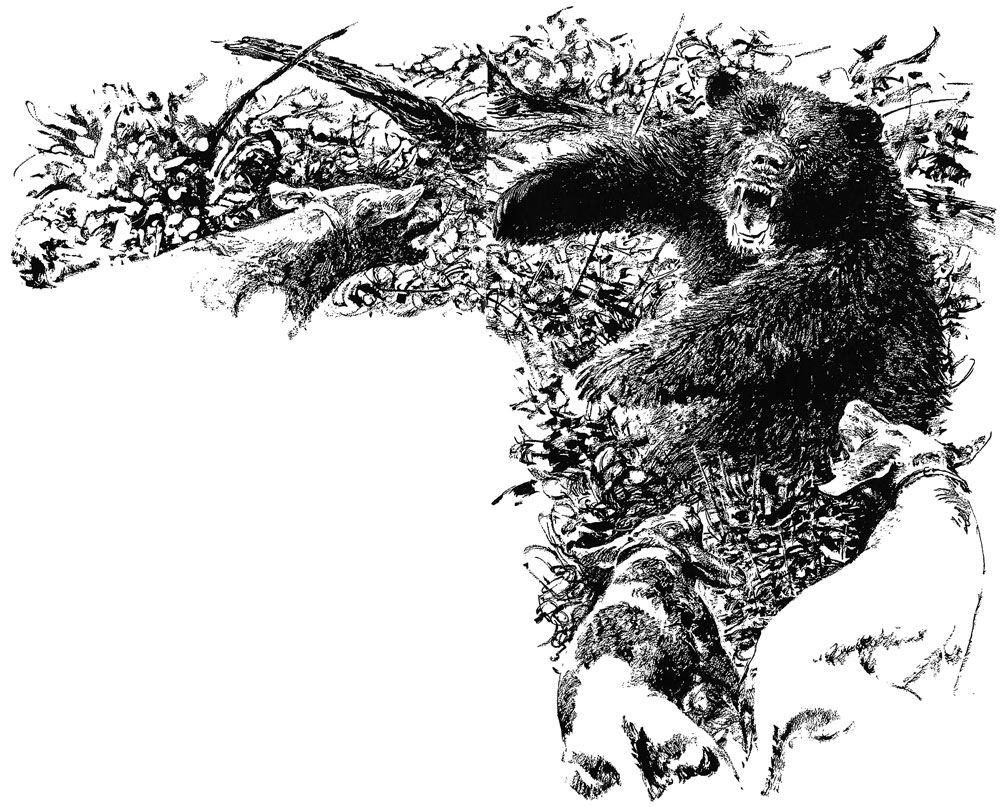

The Master unsnapped the leash and the men moved forward toward the body. A droning mass of blowflies rose above the corpse for a moment, then settled back Copper smelled the blood, smelled the birds, and identified the body as the quarry he had been following. Then he smelled something else that made him bound to his feet: a savage, feral scent that made the black hairs of his neck stand up and sent shivers of fear and excitement through his body. Bear!

Regardless of the men, Copper bounded forward and began feverishly to cast around. It was bear, all right. There was blood on his paws and he had been in a frenzy of rage; Copper could tell by the special quality of the scent. His conviction was confirmed when he hit a spot where the bear had urinated in his excitement. The urine was heavily charged with the odor only a furious animal emits.

As he was no longer tracking a man, Copper felt himself justified in giving tongue, and his deep bay rolled out, first in a long howl and then in short, gasping cries. Instantly the Master was by his side. Copper showed him where the line was; but the Master, instead of instantly winding the scent, went back and forth in an exasperating way until he found something to look at on the soft earth. The Master's inability to scent a perfectly clear line, as well as his tendency to stand for a long time staring at pointless marks on the ground, was his most irritating quality, and Copper had never grown entirely reconciled to it. The Master called over the leather-smelling man and they both looked at the ground and talked, while Copper went nearly mad with impatience. Finally the tracking leash was snapped on and he was told to go ahead.

It was no use. The bear had traveled much faster than the man and hadn't dragged his feet as the man had. Copper could only just own the line. After a short time, the Master pulled him off, and even Copper had to admit it was a wise decision. That bear was gone. By the time Copper could have puzzled out the faint trail, the bear would have been too far away to make the hunt worthwhile; besides, neither man had a gun. Copper knew that men always carried guns when they went bear hunting.

After a long, dull journey they returned to the cabin and the cars. While the men, as they always did, talked and talked interminably, Copper slept, licked the cuts on his paws, and slept again. He was intensely relieved when he was ordered back to the car and they started home.

For the next few days nothing happened. Copper, like the other dogs, was bored and restless. He amused himself by lying in front of his barrel and checking the various odors that the breeze brought him. He could just make out the cabin at the foot of the little rise where the kennels were, but beyond that the world fuzzied into a black-and-white haze, although he could barely distinguish a moving figure if it wasn't too far away. Everything looked black and white to Copper even though he could tell a considerable number of shades of gray by their comparative brightness. Copper did not depend much on his eyes, which he knew were unreliable and which had often caused him to make shameful errors. If the Master changed his clothes, Copper would often bark at him until the Master spoke so he could recognize the voice. This was very humiliating, but even while Copper was cringing in disgrace, he liked to get a good sniff in to make quite sure the figure standing over him was indeed the Master.

If his eyes were weak, his nose was quite another thing. Lying on the hill, Copper could tell fairly well what was going on in the world about him. At every moment dozens of distinct odors were pouring into his nostrils; the great majority of them the hound ignored as meaningless. Flowers, grass, trees, the other dogs, activities in the cabin - these meant nothing to him. A distant herd of deer passing through the woods, a stray dog, a human stranger, even a pheasant, goose, rabbit, or raccoon caused his nostrils to twitch as he took pains to separate the important scent from the mass of other odors. He could also tell when it was going to rain by the moisture in the wind, and distinguished between day and night by the different quality in the air almost as much as he did by eyesight.

A few mornings later, he was awakened by the ringing of the telephone in the cabin. It was still pitch black even though Copper could smell the dawn not too far away; it always began to cool slightly before dawn. The other dogs moved restlessly and mumbled annoyance at the insistent ringing, but Copper lay awake listening. When the phone rang at night it usually meant a job to do. Perhaps he would be called on again to the further humiliation of the Trigg,

The phone stopped ringing. Then lights went on in the cabin. Even the other dogs knew what that meant, and their chains rattled as they shook themselves and came out of their kennels to stretch, yawn, and relieve themselves. Copper smelled coffee, and was almost sure there was a job on. The Master never made that coffee smell this early unless he was going out.

The cabin door opened, emitting a flood of light, and the Master came out. The wind was blowing to the dogs and Copper could smell his leather hunting boots and the heavy jacket he wore when he started on jobs. Alas, there was no scent of the tracking belt that meant Copper alone was going. But there would be tracking.

The rest of the pack were beginning to leap at the ends of the chains and scream with excitement. The chorus varied from the hard chop of the two gray-and-white treeing Walkers to the deep, sonorous bay of the trail hounds. The Master shouted, "You, Chief! Strike! Ranger! Hold that noise!" The dogs sub- sided.

With the swift efficiency of long practice, the Master hitched 'up the dogs' trailer to his battered car while the pack watched anxiously. Then he came up the hill. The dogs groveled, barked, whined, and stood on their hind legs in an agony of anticipation while he made his choice. To Copper's inexpressible delight, he was selected. The Master also took Red, a young heavy-coated July hound, and Ranger, a buckskin Plott who was known as a fighter. Then he took that damned chief. Chief was a big hound weighing nearly as much as Copper. He was more catfooted than the bloodhound, faster and more belligerent. He was black-and-tan with a white-tipped tail. Because of his habit of skirting, he not infrequently hit by chance on the line that Copper was patiently working out, gave tongue, and took the pack away on it. This was one of the reasons the bloodhound hated him.

Lastly, the Master selected Buck, a long-legged Airedale, and Scrapper. Scrapper's ancestry was uncertain. He had some bull- dog, some Doberman, and perhaps a little Alsatian. The inclusion of these two catch dogs meant they were going after dangerous game. Like all the hounds, Copper feared and disliked the catch dogs. He had discovered from painful experience that the catch dogs when excited were more likely to attack the hounds than the quarry. The hounds were put together in the trailer, but the catch dogs were kept in separate compartments.

The white sun was rising in the grayish-black sky as they started. Copper didn't like riding in the trailer; it swayed too much and made him sick, so he lay down and tried to sleep, only growling a little when the other hounds fell across him in their excitement at going out on a job. The ride was not too long, and they made good time because the highway was almost deserted at this hour except for a few night-running trucks that gave off a stench of diesel oil as they passed. They reached a small town, and the car slowed down. A car was parked in the silent street, and the headlights were rapidly switched on and off as they approached it. Though Copper could see the car through the trailer's wire mesh, he could not identify it even after the Master pulled up alongside and stopped. He did know the man who got out - not immediately, but after he had talked to the Master for a few seconds Copper could smell him. This man always smelled of a special grease he used on his gun. There was no doubt about it now: they were going after some potentially dangerous animal. The grease-smelling man appeared only before such hunts.

The two men finished talking and, getting back in the cars, started off. Again Copper dozed. When he awoke, the cars were climbing up a steep grade. The air was fresher, colder, and thinner. Scenting conditions were so good that in spite of the stink of the exhaust Copper could smell pines and even some animal scents, especially deer. The cold air of the mountains made him feel better, and he stood up, swaying in rhythm with the motion of the car.

The cars pulled off on grass and stopped, while the Master came around to let them out. The captives went crazy with excitement, ricocheting off the sides of the van and throwing themselves against the door. The Master had to press the door in with the full weight of his body to get enough play to release the catch. The hounds poured out in an excited stream, and the Master waited while they relieved themselves and checked the new scents. Then he let out the catch dogs, one after another. There was a little trouble between the fighting dogs and the hounds, but the Master was watching closely and at the first growl he spoke so sharply that the dogs avoided each other,

Ahead of them rose a great cliff, painted dead black by the light of the white sun on it. Sheltered beneath the cliff stood a small farmhouse, flanked by a rambling apple orchard and a sheepfold. The air was supercharged with scents here. In addition to the smell of mice, squirrels, rabbits, and grouse on the grass, which interested him, Copper was also conscious of the odor of chickens, cattle, sheep, humans, a dog, and the aroma of food cooking. He also scented water, and hoped they could drink before starting out.

A man came from the house with a dog at his heels. Though the pack paid no attention to the man, they were all instantly fascinated by the dog. Copper could not see the dog plainly, but was quite sure he was a male, frightened, and fairly young. The man ordered him back to the house, and Copper with the rest of the pack went after him to investigate until the Master called them off.

The man took them to the sheepfold. The sheep were bleating, and Copper knew by their scent that they had been badly frightened during the night. They had urinated in their terror, and the pen smelled heavily of the urine charged with the special odor of fear that all animals quickly recognize. Although ordinarily the pack would have been indifferent to the flock, the fear smell made them prick up their hackles and move toward the fold stiff-legged. Even Copper, well broken to all domestic stock, felt a charge of gloating cruelty surge through him. (That odor meant the quarry would put up no resistance, but would lie writhing helplessly while Copper buried his teeth in the soft flesh and felt the ecstasy of the victim's death struggles through clenched jaws that odor maddened him almost like the scent of a bitch in heat. The Master ordered them off, and when the catch dogs seemed inclined to ignore him he took a stick to them.

The man who lived at the farm was pointing to the ground; the Master and the grease-smelling man bent over to examine it. Then the Master called Copper over. As the hound leaped forward, the others tried to follow but were ordered back, to Copper's great satisfaction. The instant he applied his trained nose to the spot where the Master was pointing, Copper burst into a long, sobbing cry. It was bear. It was the same bear he had scented beside the dead man. With his tail wagging frantically, he began to work out the line.

To his surprise, the Master called him off. The grease- smelling man went to the cars and came back with his rifle. Then they started toward the apple orchard, the hounds trotting over the soft gray grass under the dark leaves. By a twisted old tree stood a pile of crates, filled with apples. The heavy boxes had been scattered in all directions, and the round black fruit littered the ground. Copper sniffed at some of the apples. The smell told him nothing.

"Here, boy, here!" called the Master. Copper hurried over. Even before he reached the Master, he smelled the bear scent. Leaping forward, he began to cast about, his tail going madly as he tried to pin down the line. Red, Ranger, and Chief hurried up and also began to cast around. Ranger and Chief had the scent, but young Red was still trying to find out what the excitement was all about.

Then, then it came! Full, strong, and fresh. Copper knew he was on the line and smelled the tracks themselves; not scent blown out of them by the morning breeze. He went a few feet to make sure and then broke into his deep, bell-like bay. Instantly every dog in the pack - even the catch dogs - left whatever he was doing and ran to Copper. Ranger and Chief sniffed desperately and then simultaneously broke into the steady cry of hounds on a scent. Red had more trouble, and then he too gave tongue.

"Go get 'em, boys. Woo-whoop!" shouted the Master. The pack was streaming across the orchard now, swept along by the sound of their own music as much as by the scent that floated in front of them. Copper was following the trail itself, while Ranger and Chief, running on either side of him, were picking up the scent swirls, for the warmth of the rising sun was making the scent rise from the tracks, and a slight breeze distributed it. Red was following Copper to be quite sure of the line. The catch dogs were at the tail, only occasionally getting wisps of scent that made them yelp with eagerness.

The scent held well in the forest, and the pack pressed on, reassuring one another by their rhythmical baying that they were all still on the line. Where the woods were open, the scent lay breast-high and the hounds were able to follow it without dropping their heads - a great advantage. In the deeper woods where the sun had not as yet penetrated, the air was cold and the scent still lay on the ground. Here the hounds were forced to drop their heads, and this slowed them. At times the scent failed completely. At such times the pack stopped their baying and anxiously fanned out, each hound working on his own to find the line. Copper usually found it. He knew all the best places to check the hollow formed by two roots at the base of a tree, a clamp spot where the scent might cling, a protected hollow where the scent might have drifted and could not rise again. Often he was able to take it from bushes that had touched the bear's sides. The scent particles clung to the oily surface of the leaves, while it would not adhere to dead leaves on the ground or to the bare earth. When he was sure, he would speak and the rest would run over and cast out ahead of him. Occasionally one of the other hounds would strike something and speak to it doubtfully. Copper would hurry over to check the spot. The rest would wait until they heard his affirmative deep bay.

Once when the whole pack had been at fault for several minutes, Red, the young July hound, shouted eagerly. No one paid any attention to him, for Red had never opened on a line before. But the puppy kept pleading, until finally Copper went over to investigate, fully expecting to find nothing. Red indicated the spot and stood back anxiously while Copper applied his expert nose. To his surprise, there was the scent. A lesser hound would have gone on and opened on the line farther ahead, as though he had discovered it himself, but Copper would not stoop to such acts. He instantly opened on the line, confirming the pup's yelps. The Pack rushed over and soon were in full cry again. After that, whenever Red spoke on a lost line he was awarded the same respectful attention as the older hounds

Then they came to a blowdown where the wind had knocked down a stand of sharply scented hemlocks. The packs slithered over the trunks until they reached the other side. Here they checked. Somewhere in the blowdown they had lost the scent. Either the bear had turned sharply at right angles and come out at a different spot or the scent would not lie on the sun-baited ground on the far side of the blowdown.

The pack started casting - working out in ever-increasing circles, trying to pick up the trail again. They were still at it when the men caught up with them. The Master tried casting them himself , putting them on at various places where the bear might have come out of the blowdown, but although the hounds worked hard they could find nothing.

Copper left the rest and crawled back through the blowdown to the last spot where he could positively identify the scent. He gave tongue on the old track and then came slowly back toward the blowdown. There was still some dew under the forest timber that held the scent, but the fallen trees in the blowdown were exposed to the full rays of the sun. It was noticeably warmer here, and the heat gave Copper an idea. He stood up on his hind legs. Ah, there it was! Very faint, but detectable. The scent was floating just above his head when he reared up. As the hound could not walk on his hind legs, he would stand up to get the scent, drop back on all fours, take a few steps, stand up again, and so on. Each time he raised himself and caught the ghost of the scent, he would give a low cry. The cries came in a slow, well-spaced Bow . . . bow . . . bow, as he advanced. With nose still strained upward he started across the blowdown. His feet slipped and plunged in between the trunks, but he was higher now and his straining nose could barely touch the floating line. His cries slowed yet he kept on. When he reached the hard ground on the other side, he had to stand up again to reach the odor, but he kept on through the still questing pack.

Now the other hounds began to understand what he was doing. They also stood up on their hind legs to test the upper air, some straining up so far they fell over backward. Chief caught the scent and gave tongue. He followed Copper, and they worked their way into the pine forest. Then Ranger began to speak, and finally Red. Under the trees, the scent dropped to the ground again. Here the hounds were able to follow it easily, and burst into full cry.

They quickly outdistanced the men. Now the other hounds had moved into the lead, for the scent was good, and Copper, never a fast dog with his heavy, bloodhound build, was slower. Red was in front, going at such a rate that if the bear had turned off sharply he would be sure to overrun the line. Behind him came Ranger and then Chief. The catch dogs were in the rear, following the hounds for they could hardly own the line even now.

The scent was getting stronger. The bear was close. Copper dropped back more and more. His legs were stiff, his lungs burned, and in addition he had no desire to come up with an infuriated bear. He knew bears by experience. They were dangerous, and Copper was no fighter.

Suddenly Red began to scream with excitement, and at the same moment came the sound of smashing brush. Red had sighted the bear. Now Ranger and Chief stopped giving tongue and broke into the viewing cry. In spite of himself, Copper caught the excitement and put on an extra burst of speed. The catch dogs tore past him, Scrapper snarling and slashing at him

to make the hound get out of the way. Then through the hysterical yells came a deep-throated bellowing. The bear was turning at bay. He had a system of tunnels in the blackberry bushes, and when the pack tried to follow him he turned and charged. The dogs fell over each other trying to avoid him. Copper, mad with excitement, plunged on through the tangle that clung to him and tore at his ears.

Somewhere in the bushes a fight was raging. Hazel limbs were snapping like gunshots. Then Copper heard a yelp from Red as the young hound took a blow. Now the bear growled in pain. One of the catch dogs must have taken a hold. The screaming of the dogs rose in intensity, and Copper rushed on regardless of danger. He saw the red body of the July hound go sailing over the bushes. Copper was warned and slowed down. As he broke through the last cover, he saw the bear.

The great black animal had backed against a fallen tree so the dogs could not take him from behind. He stood there swinging his head back and forth, champing his jaws as the dogs rushed at him by turns. The whole place was filled with his powerful odor, but there was no scent of fear.

The catch dogs had taken up their places one on either side of him while the hounds ran around behind them. First Buck and then Scrapper would leap forward, and the bear would swing his head to face the adversary. Then the other dog would spring in, tear out a mouthful of fur, and jump back to avoid the bear's return blow. While he was spitting out the fur, the other dog would bound forward to pull out another mouthful from the bear's other side. They were making no real attempt to attack- only to hold him.

But how long could they hold him? Twice the bear made an effort to leave the tree and continue running. Once he started going, he could easily outrun the pack in this heavy cover. The dogs knew it and even the hounds rushed in to help the catch dogs snap at his sides and force him back. But if the bear really decided to break, they could not stop him.

The sound of the Master’s horn came. He was signaling the pack that help was on the way. At the call, the catch dogs moved into position. When both were ready, Buck gave a quick, sharp bark. Instantly, Scrapper rushed in, making a feint at the bear’s side that drew him out slightly from the protection of the tree. Buck promptly leapt in and grabbed the bear’s ear. Scrapper bounced forward, snapping and barking to keep the bear from turning on his friend, while Ranger and Chief tried to help distract the animal. Buck managed to fling his body over the bear’s neck, still hanging onto the ear.

The bear stood up on his hind legs, reaching behind him for the Airedale, As he did so there came the stunning crack of a rifle shot. The bear must have been hit, for an instant later came the acid scent of diarrhea as the bear emptied his bowels. The hounds screamed at the odor and flung themselves forward, tearing out mouthfuls of fur. Copper could no longer control himself and joined the attack,

Another shot cracked out. The bear seized Buck in both paws and flung him away into the bushes. Then he turned on the rest of the pack. Scrapper, leaping back to avoid a blow, collided with Ranger. Instantly he turned with insane fury on the Plott, and the two dogs rolled on the ground together, biting furiously and feeling for each other's throats. Copper saw the Master tearing through a mass of honeysuckle with a small gun in his hand. The grease-smelling man was there too, yelling something and waving his rifle. The bear was apparently completely absorbed with the dogs, yet suddenly he whirled and charged the Master.

The Master tried to jump back, but his foot caught in the honeysuckle and he fell. The bear was on top of him. The catch dogs were gone, and even at this terrible moment Copper could not bring himself to close with the bear. Then Chief charged in from behind. Closing his forefeet under him, he slid under the bear and seized the raging animal by the testicles. The bear's jaws had met in the Master's shoulder, but this pain was too terrible for the animal to take. He whirled around, but Chief still hung on, although he was lifted off his feet. The Master rose on his elbow and fired into the bear's side with his small handgun. The grease-smelling man also fired. The bear went down, blood pouring from his mouth - the thick, rich-smelling arterial blood that means death. The dogs poured over him, even Scrapper and Ranger forgetting their differences as the smell hit them. Straining in different directions, the pack stretched him out between them while the grease-smelling man fired shot after shot into the body.

When it was all over, Copper lay down with a delicious feeling of satisfied exhaustion. It was much the same feeling he had after having well served a bitch. He was drained of strength and strong emotion. A delightful lassitude filled him.

The Master rose and limped toward them, Copper rose to greet him, proudly wagging his tail in conscious self-esteem for having done a good job of trailing. The Master paid no attention to him. He went over to Chief and, taking the Trigg's head between his hands, spoke to him in the love talk that once he had used only to Copper. Watching them with savage jealousy, Copper knew that his day was done and that soon there would be a new leader of the pack.

2. The Fox

His first memory was that of hearing an eager scratching at the mouth of the den, followed by excited whines. The fox pup was not frightened; instead he was excited and curious, for the noises were not unlike fox noises and he knew of no reason to fear them. His mother reacted differently. In a moment she was on her feet, hissing and snarling, and although the pup had never heard these sounds before he instantly recognized them as danger signals. Then she gave off the terrible scent of fear, and even though this was a new scent to the pup he knew it meant the family was in dire peril.

His brothers and sisters were whimpering and wetting with terror, but the pup did neither. He kept his wits. He had always looked to his mother for guidance and now he gave a plaintive yip meaning "What do you want us to do?" At once his mother spun around and picked him up by the scruff of his neck. Even in her excitement she was careful not to let her canine teeth close over his slender vertebrae, and pushed her jaws far down until she could lift him with her molars. Then she ran down one of the long passageways of the den. This den was a huge affair that had been used by generations of foxes, and some of the passageways were fifty feet long. There were ten boltholes besides the main entrance, and it was toward one of these boltholes the vixen ran.

She stopped just short of the entrance. The ground trembled with the stamping of men's feet, and their voices came clearly through the hole. There were other dogs, yelping and barking, half mad with excitement. The vixen backed down the burrow and stood for a moment, tormented by indecision. Then she dropped the pup and ran back for another.

The pup lay cowering as he listened to the sounds around him and smelled the new and terrifying odors that gradually seeped along the tunnel. He heard a dog forcing its way into the earth, and then heard it scream. The vixen had grabbed it by the nose and bitten through to the cartilage. He listened to the gurgling noise of combat as the half-strangled dog tried to tear himself free. Above, the men were shouting and stamping on the ground. Somewhere in the earth he heard a rumbling noise that at first he could not identify. Then he realized it was a second dog that had been put down another hole and was racing to his friend's help. He heard it reach the main den and yell with excitement when it saw the vixen. Then the whole earth reverberated with the screams of the vixen and the cries of the terriers.

The rumbling noise began again and went through the entire system of passageways. His mother was running through the earth with the dogs after her, trying to lead them away from the pups. Then came the most awful sounds he had ever heard: the death cries of his brothers and sisters. A third terrier had been sent down the main entrance, and found them.

His mother suddenly appeared beside him and dropped panting. They lay with their noses touching while the roar of the dogs tearing about through the passageways looking for them echoed through the earth. His mother rose and, writhing around in the narrow pipe, began to dig desperately at the roof. The earth fell in showers around her, gradually blocking up the tunnel. She lay down again, panting, and they listened to the whining of the frustrated terriers.

Coming down the burrow, and separated from them only by the thin earth barrier, they heard the footsteps of one of the terriers. The foxes lay motionless, not daring to breathe. They heard the dog come to the fallen earth and scratch at it. Neither fox moved a muscle. The fallen earth had not only blocked the tunnel; it had also cut off the scent, and the dog abandoned the task, backing slowly out of the passage because he was too big to turn. The foxes resumed breathing.

Above them still came the voices of the men and the drumming of their feet. Now their scent was leaking down to the foxes, and the pup, curious even in this crisis, lifted his head slightly to bring his nose into play. By lying perfectly still the foxes had largely cut off their scent, as the odor was spread by the heat of their bodies when moving; but the vixen's activity in collapsing the roof of the tunnel had filled the narrow pipe with her scent, and that still lingered. With the two animals crowded together in the pipe, the passage grew warm and, as the temperature increased, the scent began to rise out of the bolthole and catch in the tangle of honeysuckle that covered it.

The terriers had come out of the earth now, and the pup could tell by the slower breathing of his mother that she was no longer so frightened as she had been. Also, the fear scent was beginning to fall away. The men had tramped over the entrance of the bolthole several times without noticing it, and they would soon leave.

One of the terriers raced by overhead. As he scrambled over the honeysuckle tangle, the foxes heard him stop suddenly and begin to sniff. Again they stopped breathing.

The terrier was forcing his nose through the vines until his nostrils were in the bolthole itself. He sniffed louder and then broke into an eager yelping. Instantly they heard the other dogs racing to him. The vixen pushed the pup behind her with her nose and crawled up the pipe to meet them.

Now the men were there and the honeysuckle was ripped away, A terrier started down the hole, but he was too big to make it. A man pulled him out by the hind legs, and another, smaller dog was put in. This dog managed to worm his way in to where the pipe was larger. The foxes heard him coming. There was a narrow shelf along the side of the pipe, and the vixen crawled onto it. She let the little dog pass below her and then suddenly seized him across the loins with her long, pointed jaws. She clamped down with all her strength and had the satisfaction of hearing the backbone snap. The dog screamed in agony and lay writhing in the pipe, paralyzed.

Above them came the furious yelling of men and dogs. Now came a thump! thump! thump! The men were digging down to them. At once the vixen slipped off the shelf and, running to the wall of earth that blocked the passage, began digging desperately, but before she could break through another terrier had come down the pipe. He managed to wriggle over his mortally wounded comrade, and the vixen was forced to turn to face him. Wiser than his friend, the terrier made no attempt to attack. Instead he began the chop bark that meant "Here she is! I'm holding her at bay!"

The men recognized the cry and began digging in earnest. There was nothing the vixen could do now. When she tried to break through the wall, the terrier rushed at her, growling and snapping so that she was forced to turn. When she attacked him, he retreated up the pipe, meeting her attacks with open jaws. She could not get past him, and if she had there were the men and the other dogs waiting for her.

The top of the tunnel caved in, splattering dog and foxes with loose dirt. The men had broken through to the pipe. The vixen made one last frantic effort to escape, forgetting in her frenzy even her precious pup. She leaped toward the light and air. Quick as she was, the terrier was also quick. As the fox bounded out, he sprang forward and seized her. Dog and fox came out together.

The pup trembling in the now open pipe heard the horrible sounds of combat above him: the fierce snarls of the terriers just before they took their holds, the hissing screams of his mother as she fought hack, and the yells of the men. Then came the guttural sounds of worrying as the terriers made their kill.

The pup never moved. He knew his best chance of safety was to remain absolutely still. He lay in the pipe, a little ball of woolly fur, with only his eyes - just changing from baby blue to yellow - showing he was alive.

The dogs were still worrying his mother's corpse when one of the men gave a cry and, reaching down into the pipe, picked him up. The pup did not move until the man's hand actually closed over him and he knew concealment was no longer possible. Then he gave a sudden banshee-like screech and buried his little milk teeth in the man's thumb. The man started, and the pup felt himself grabbed by the neck so he could no longer bite. He instantly realized the situation, and promptly relaxed. There was no longer any use in struggling. pie dangled limply, watching his chance to make a bolt for it.

He was put in a bag and carried to a car. Throughout the long drive, the pup lay quietly, his mind almost a complete blank. Luckily for him, he was incapable of speculating about the

future, and so did not suffer the agonies of apprehension that a human would have endured. At last the drive ended, the car stopped, and he heard voices. The bag was lifted, and he was carried away from the car. Then it was opened, and he was gently shaken out on a floor.

The pup lay there looking up at the man bending over him. The man was talking, but the words and even the tone meant nothing to the pup. He was mainly conscious of odor: the terrifying smell of the man, the strange smell of the room, and the smell of a dog. There was a dog in the room not much bigger than himself who came over and sniffed at him. The pup snarled automatically, but he was not really frightened. The dog's tail was wagging; there was no scent of anger; and the dog's actions were sufficiently foxlike for the pup to recognize that the animal meant to be friendly.

The man spoke to the dog, who hastily retreated. Then the man tried to touch him. The pup twisted himself around to meet the extended hand with bared teeth, for the man had brought his hand down from above in an action recognized by both dogs and foxes as an aggressive movement. Another fox, attacking, would have come down from above in just such a movement to get the neck hold. The dog, on the other hand, had come in on the pup's own level. The man withdrew his hand and then extended it again, this time moving it along the floor. The pup still snarled, but after a few seconds allowed the hand to touch his neck.

The man began to rub him under the chin and scratch back of his ears. In spite of his fear, a delicious sense of well-being flooded through the pup. He lay in an almost hypnotic state while the hand massaged him, yet at the same time he was tensed to bound away at any sudden movement.

The pup tamed rapidly. He identified with the little dog far more readily than he did with the man, even though the man fed and cared for him. The fox pup and the dog spoke the same language. The language was not vocal, but was made up of signs and gestures, and to a certain degree of scent. The dog smelled more like a fox than did the human, and, more important, he behaved like a fox. When the dog first attempted to play, the pup was suspicious of his intentions. He instinctively swung sideways to the dog, feinting with his brush as a shield and striking at the dog with his flank to bowl him over. When he realized the dog was only playing, he abandoned these tactics. The play resembled fighting as the two animals rolled on the floor together, biting at each other and trying to get the other down, but the tactics the fox used were those he would have used in killing game - the loin grip and the neck hold. Both of these holds are effective in killing a rabbit or woodchuck, but in a fox fight the two opponents are so nearly the same size that it would be impossible for one to get either of these grips on the other except under extraordinary conditions. In using them on the dog, then, the fox was merely playing that the dog was quarry rather than an enemy.

The fox quickly learned his name - the humans called him "Tod" - but he would almost never come when called. He knew quite well he was being called, but he always wondered why they were calling him. Perhaps they had some sinister motive. If the calling became insistent, he would sneak quietly through the house, taking advantage of every chair and sofa until he could see the person calling. If the person had a toy, food, or was even lying on the floor patting the rug, he would joyfully bound in; but if the person had no obvious reason for wanting him, Tod would watch for several minutes and then softly steal away.

At first he had been given the run of the house, but now he was locked up at night in a bare room. Tod hated to be confined and deeply resented this treatment. He learned that after the supper dishes were washed, he would be locked up, so as soon as the dishes were put in the sink, he would quietly steal away. First he hid in the downstairs hallway, which, being dark and seldom used, seemed a good place, but he found that when both the man and his wife went looking for him, they could block both ends of the hall and he was sure to be caught. There were two upstairs hallways, and he tried both of them, one after the other. The same thing happened. He then tried hiding in a room, only to find that when the humans saw him they could shut the door and bottle him up. He tried all the rooms in succession, with the same result. Finally he learned to keep moving. Then it was almost impossible to trap him. As this trick had proved successful, he followed the same pattern rigidly from then on, always going along the same course because the first time he had followed that particular route he had escaped. Tod made no attempt to understand why a certain device succeeded or failed. If it failed he abandoned it, and if it succeeded he meticulously duplicated the same pattern in every detail over and over again.

As he grew bigger, the man did a number of curious acts that puzzled and somewhat annoyed Tod. He would throw some object on the floor, and the dog would bring it to him. Then he would throw it out for Tod. Tod understood what the man wanted him to do, and would pick up the object; but as there was no reason he could see to bring it to the man, he would carry it off. The man would catch him, put the object in his mouth, and close his jaws over it. Tod hated this performance, and fought it so furiously that the man gave up. Tod was willing enough to play, but he saw no reason why he should do something he did not want to do; and as he had no desire to please the man as did the dog, he would never retrieve.

On another occasion the man laid out a series of white metal bowls, each with a small piece of meat in it. Tod went down the line collecting the meat. One bowl had some wires running to it, the wires being attached to a small box that had a strong acid odor. Tod paid no attention to this arrangement, but when he touched the bowl he received a shock that made him jump. Tod carefully avoided that bowl in the future. The man tried placing it in different positions in relation to the others, but this made no difference to Tod, who could instantly recognize it. Finally the man removed the wires, and still Tod refused to go near the cursed thing. Months later, the man offered him food in the bowl, but Tod remembered it and shied away. No matter how the man washed the bowl and mixed it up with the others, Tod could tell it. Although all the bowls seemed identical, each had almost microscopic differences, and Tod with his keen sight could easily distinguish one from the others. Tod would never forget that particular bowl as long as he lived, and wires or no wires he would never go near it again. When the same experiment was tried on the dog, the little terrier got several shocks before he learned to associate that bowl with trouble, and a few months later he had forgotten about his experiences and ate from it as willingly as from the others. Tod needed only one lesson, and he never forgot.

The man began to take Tod out for walks, at first keeping him on a long lead. Tod loved these walks, He was bored in the house, and there was so much to see and smell outside. After one walk, the man had only to approach the drawer where the lead was kept and Tod was bounding with delight, lying down to wiggle and whine with delighted anticipation, holding up his head so the lead could be snapped to his collar. Getting Tod back to the house was another proposition. As soon as he saw they were headed back, he would fight the lead, lie down, or brace himself with all four feet against the pull.

At last the man tried letting him run free. Now Tod was perfectly happy. He ran around checking new scents and enjoying the sights. He was fascinated by the farm animals, especially the sheep. They had a heavy odor that attracted Tod, and the first time he encountered the flock he ran eagerly toward them. The sheep scattered in all directions, with Tod bounding joyfully in pursuit. As they scattered more and more, Tod began to herd them, bringing the flock together. Delighted at his power over these stupid creatures, he drove them from one end of the pasture to the other, learning how to keep the Hock bunched up and how to change their course without having them separate. When the sheep grew too panicky, Tod would stand still until they had quieted down, often dropping his long nose between his forepaws, with his hindquarters elevated in the same attitude he used when playing with the man or dog. Sometimes he would crawl in among the sheep on his belly so slowly and quietly they would stand motionless watching him. He would worm his way through the Hock in this manner, proud of his ability to fool the animals. Then, springing up, he would split the flock and drive one half around the pasture and the rest go where they would. He was much too small to hurt the sheep, and had no evil designs on them. Yet he had a desire to herd and drive them that he could not explain.

Tod had a remarkable ability to differentiate between various sounds and to interpret even human tones of voice. Once the terrier jumped a rabbit that sprinted down a fence line toward a road where cars were moving. The dog sped after the rabbit; and Tod, although he had not seen the rabbit himself, ran after the terrier. As they neared the road, the man started shouting to them. Both animals heard him, but the dog, intent on the rabbit trail, refused to obey, and naturally Tod kept with his friend - he seldom came when called under any circumstances. When they were close to the road and the speeding traffic, the man' s voice took on a new tone. He yelled with fury. The dog continued to ignore him, but Tod stopped short, turned to look at the man in surprise, and then hurried back, fawning at the man's feet apologetically. He knew quite well from the tone that this was no ordinary command; the man was intensely serious.

When autumn came, Tod was delighted to find great new vistas opening. From the top of a hill he could see vast distances, unhampered by tall grass or leafy bushes. Walking was now a real pleasure, for Tod had trouble making his way through dense cover and always preferred open country. Everything had become open country, even the woods that he had hitherto avoided, for the underbrush was gone. He loved the dry leaves, and batted them around with his nimble forefeet, springing up to catch them in the air with snapping jaws or rolling over and over in them. It became harder and harder for the man to entice him back to the house, for being outside was too much fun. Food had no particular attraction for him; he was too well fed, and could quite easily go for forty-eight hours without eating. Also, he was growing bigger, stronger, and more self-confident. Sometimes the man could lure him back with a mechanical toy that always aroused Tod’s curiosity, but he spent several nights out, always turning up in the morning for his bowl of milk.

It began to grow colder. Tod did not mind the cold; in fact he rather enjoyed it, but in the early morning when the ground was coated with hoarfrost, it upset him not tn be able to smell. He ran around sniffing desperately, afraid that something had gone wrong either with him or with the world. He did not relax until the sun started a thaw and scenting conditions were better. Just to reassure himself, Tod would dart around the farm, snuffing at all the old, familiar spots. Then he had a real surprise. Trotting down to the pond for a drink, he found the surface covered with a thin, hard substance. Tod smelled it, patted at it with his paw, and then struck it repeated blows with his pile-hammer nose. The stuff cracked, and Tod got his drink.

One evening Tod refused to return to the house in spite of all the man's cajolements. The atmosphere was oppressive and pressed down on his eardrums. He did not like the smell of the air; it seemed thick, somewhat like the heavy, moisture-charged air before a rain, yet this was different. It was more dense and confining. Tod reacted strongly to anything new; it either fascinated or terrified him. This terrified him. He ran around whimpering until finally the man left him, Then Tod got lonely and went to the back door. He sniffed under it. He could smell the people and food inside, and hesitatingly lifted one paw to scratch; then thought better of it. He was too distraught to think clearly, and ended by running around the farm several times and finally curling up under the woodpile, Scenting was good, and this partly reassured him, as whatever the danger was, he could tell when it was coming by his nose. At last he went to sleep.

When he awakened, the world had turned white. Tod sat up astonished. He was a little frightened but mainly curious. He dabbed at the stuff with one paw and studied the curious way it crumbled. He poked at it with his long nose and was charmed when his nose plunged into the stuff. Now he was thoroughly excited. He bounded out into the snow, diving from one drift to another, knocking it about by quick sideways motions with his nose. When miniature snowballs formed and rolled down the drifts, Tod chased them, biting gaily and then trying to find out what had happened to the vanished spheres. He was still rollicking happily about when the man came out. Tod was so happy he allowed himself to be picked up without a struggle and carried inside for breakfast. As soon as he was through eating, he anxiously scratched at the door to be let out again. This time the man and dog went with him, and Tod had a magnificent time making a complete fool out of them both, for often he could run on the surface of the snow when his two companions floundered helplessly in the drifts. This was exactly Tod's idea of a joke, and he made the most of it.

As the winter continued, Tod grew increasingly restless. His testes began to swell and trouble him so that he sometimes twisted around to bite at them. He grew more and more irritable, snapping at the dog, and several times he bit the man severely when picked up. He stayed away more and more, returning to the farm mainly to pick up food at the garbage dump in the far pasture; but sometimes he still craved companionship, scratching and barking at the back door until he was let in. At such times he would run ardently from the man to the dog, doing everything to show how glad he was to be home. For a day or so he might stay at the farm, following the man everywhere he went, going contentedly to the once-hated room at night and being even tamer than the dog. Then the throbbing would start in his swollen testes again, and he would grow restless and irritable.

His coat, which had been lackluster and shabby, was thicker and so much more colorful that he seemed like a different animal. His back became a burnished red with golden tints. His chest and belly turned a creamy white, while his eartips and lower parts of his long legs were a rich black. His brush became enormous, until it was nearly half his own size, while a snowy tassle appeared on the tip. A slight but noticeable ruff appeared around his neck that stood out when he was excited. Because of the ruff, his ears seemed more prominent and his thin nose was accentuated. His face resembled an inverted triangle with the apex greatly extended. During the summer he might have been mistaken for a small yellow dog or even a large cat. Now he was unmistakably a fox.

Tod spent hours running aimlessly through the fields or along the edges of woods, looking for something, he knew not what. Occasionally he would catch a mouse and far less frequently a rabbit, half frozen and unable to put forth its best speed. He attacked his quarry with a fury bordering on hysteria, growling as he killed and then flinging it about in an orgy of ferocity. He seldom bothered to eat it, for in killing he was striving to find a relief for the mysterious urge that possessed him. The urge was partly satisfied by the wriggling and squealing of the prey and the taste of hot, salty blood, but within minutes the agonizing restlessness would return and Tod would race on and on, knowing that only by exhausting himself could he rest and sleep.

Occasionally the urge would temporarily disappear, and then Tod was rational again. He would return to the garbage dump to look for food, although he no longer scratched at the door. One winter evening he saw the man on his way to the barn, and Tod ran joyfully to greet him. For nearly an hour they played together as they had often played when he was a puppy - Tod rushing in to bite playfully at the man's outstretched hands, grab any objects thrown him, and dash around with it while the man chased him, and once while the man was kneeling, even jumping on his back and nipping his ear. But whenever the man tried to catch him, Tod ducked away. He did not want to be confined, and his wild life was making him increasingly distrustful of any human.

One night. while Tod was sleeping, thoroughly exhausted, under a blown-down pine, he was awakened by a distant scream. It was a shrill, eerie sound, charged with hatred and terror. Tod shuddered at the sound, and lay still. The cry came again and again, growing even more shrill and vindictive. Gradually Tod became interested. He was always interested, if frightened, of anything new, and he had never heard a noise like this. The, too, there was a quality of fear in the cry that lured him. Tod automatically reacted to the sight or sound of any living creature in distress. When the sheep had run, he had chased them furiously, desiring only to sink his teeth into the frightened animals, but when they had turned at bay Tod had promptly stopped. Once he had heard the scream of a rabbit and run eagerly to the spot, for the hopeless terror in the noise had set his blood pounding. When he found the rabbit in the grip of a great horned owl that clicked at him with its hooked beak and spread its great wings, Tod had hastily retreated. This cry was not. unlike the cry of the doomed rabbit, and might well mean some creature was in dire straits. If so, killing would be easy, and killing the helpless always appealed to Tod far more than killing the strong.

He rose and trotted toward the noise. It had stopped now, and Tod hesitated, one foot upraised, snuffing the wind. It was against him, so he made a long circle to get downwind. As he loped along, a scent struck him that brought him up sharply, It was such a scent as he had never known. It was alien, uncanny, alarming, and yet as he inhaled it the pressure in his testes began to mount until it was almost unbearable. Tod ran back and forth, whining, snapping at the air in an agony of pain and fear, yet the odor drew him forward as though pulled by an invisible wire.

Agonized with suspicion, awe-stricken, furious with himself, Tod still crept closer, taking advantage of every bit of cover. The painfully exciting scent was now heavy in the air. There was a little glade ahead, and by the light of the full moon Tod saw something dart from the shadow of a tree into the even deeper shadow of laurel thicket. He dropped and lay waiting for it to reappear. Suddenly the squall came again, so close it made Tod start. The creature had stopped by the laurel, and was crying. Tod lay listening and watching, tom by conflicting emotions.

A night breeze swept through the grove, making air currents eddy. The squalling stopped. Tod knew the creature was aware of his presence; he knew because he could no longer wind it, and when he could not wind something, then the actions of creatures like the dog and the sheep had shown they could wind him. Also, the abrupt stopping of the squalling told him that the creature knew he was there. He was tempted to run, but did not dare reveal his presence or turn his back.

The creature came out of the shadows and approached him. Tod watched it come with apprehension tinged with interest. It was somewhat smaller than he was, which partly restored his confidence, and its motions were not belligerent; Tod's fine eyesight could detect the slightest motion of belligerency even more readily than he could tell the difference between one feeding dish and another. He rose to meet it.

The creature stopped, cringed, and began to whine. Tod studied it critically, checking with both nose and eyes. It had two odors: one was the strange, overpowering scent that had drawn him to the glade, and the other was the creature's personal scent. Tod gradually realized this scent was akin to his own. He was increasingly more interested, and advanced.

Suddenly there was an interruption. Another animal bounded into the glade. This stranger was fully as big as Tod, even slightly larger. It stopped short on seeing him. The vixen ran back and forth between them, whining and cringing.