Don Trent Jacobs

Primal Awareness (Preview)

True Story of Survival, Transformation and Awakening with the Raramuri Shamans of Mexico

Front Matter

Title Page

Primal Awareness

Don Trent Jacobs

Inner Traditions

Rochester, Vermont

Dedication

To Mary Balogna, who never knew the wondrous influence of her words on me; to William Dunmore of England, who taught me that humanity’s only shortcoming is the inability of its members to express their full, positive potentiality; to Jack London, whose failures were more inspirational for me than his fame; to Jack London’s daughter, Becky, who showed me the beauty of humility and the tranquillity’ of grace; to all of my family for their never ending loyalty and love; to the ancient and living ooru’ames, especially Augustin, who helped me come to know the way to harmonious living; and to all the primal souls of the world who, in spite of great pressures to do so, refuse to sever their connection with the invisible realm that complements our life on Earth.

Acknowledgments

WHEN THE RARAMURISIMARONES OF MEXICO, the most traditonal non-Christian Native Americans in Copper Canyon, offer thanks for the many gifts of life, they acknowledge the synchronistic partnerships responsible for their joy and fulfillment. In the same way, I offer thanks to the following people who have in some way contributed to the creation of this book:

My wife, Beatrice, who believed deeply in this project, and was supportive of my taking the risks of Copper Canyon; her editorial and emotional support have been invaluable.

Jon Graham of Inner Traditions, who saw the truth and utility of the CAT-FAWN Connection. Rowan Jacobsen of Inner Traditions for his fine editing and honest criticism.

My colleagues at Boise State University for their willingness to stand behind my indigenous approach to curriculum development, especially Roger Stewart, Lamont Lyons, Roberto Barruth, Sandy Elliot, Cliff Green, Ellen Batt, and Molly O'Shea. And to Greg Cajete of New- Mexico State University for his assistance.

Lucy- Stern; Brian and Norma Ellison; Bob and Marcia Willhite; Steve and Kathleen Wilson; Bill and Karen Sherrerd; Lorry- Roberts; Dan Millman; Sam and Jan Keen; Barge Levi; Wade, Margarette, and Phil Brackenbury; Larry- and Patti Lalumondiere; Randy and Deirdre Rand; Bill and Darlene Salidan; and Helmut and Katherine Relinger—all friends and neighbors whose own journeys toward a higher consciousness have in many w-ays inspired my own.

Lorri Roberts, Milt and Liz Van Zant, Pat and Shannon Kuleto, Marty and Salvador Giblas, Suzanne and Richard Langford, Randy' and Dierdre Rand, Howard and Springer Teich, Karen and Leo Bourke, Pam Morris, Brian and Norma Ellison, Molly' O’Shea, and Joan and Jack Garnett, who understood my Copper Canyon mission, supporting it with love and dollars. Edwin Bustillos and Randy Gingrich, whose courage and determination to save the Raramuri Indians of Mexico and their land is a model for us all, and without whom I would not have made contact with Raramuri simarones of the Sierra Madre wdio, in spite of their experience with outsiders as destroyers, accepted me into their lives with open hearts.

Dave Carr, who joined me on the first expedition into Copper Canyon in 1983 and felt the magical energies of the Raramuri world.

Howard Teich for his enthusiasm for and dedication to the solar-lunar metaphor and his continuing collaboration with me for more than a decade.

My daughter, Jessica, and her husband, Paul, for reminding me that the future is worth creating today.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge the reader of this book, who picked it up for all the right reasons and who will ultimately be responsible for applying its message.

Note

I have had wolves and horses in my life and in my dreams for as long as I can remember. According to Oglala Lakota beliefs, if Wolf is in one’s dreams it is a call to adventure and to exploration of the world so that newly found and newly understood information can be reported back. Wolf tells a person to be a teacher for Mother Earth, so that all two-leggeds can reach out to a higher consciousness and expand on the great truths Nature has to reveal. If Horse is in one’s dreams, this is an encouragement that the powerful spirit forces, which have not forgotten the Natural Way, will be there to help if called upon.

Augustin Ramos, a respected Raramuri shaman, once asked me, “If the Rardmuri die, along with the animals and the trees, do the white people think that they will go on living?” I was silent. He then said that there were many stories about the world coming to an end in the near future, but that if we all remember how to think well, it will not happen. He told me I might be able to help people remember this if I listened carefully each day to the winds that come from the West and to those that come from the East.

I do not think Augustin knew the Oglala Lakota’s belief that the East wind is represented in the sacred hoop by the Wolf and the West wind by the Horse.

I do not believe, however, that this is just a coincidence.

Preface

The study ... [of indigenous people]... does not reveal a Utopian State in Nature; nor does it make us aware of a perfect society hidden deep in forests. It helps us construct a theoretical model of society which will help us to disentangle what in the present nature of Man is original, and what is artificial.

Jean-Jacques Rouseau, Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality

There are things we can share with the white man. There are things he can show us. We can have this exchange only if the white man leaves us to learn from ourselves, from the Earth and from the spirits, as we have always done.

Otherwise, we will die with our philosophy and white people will starve as they continue to exchange the animals and the trees for things that are manmade.

Augustin Ramos

THIS BOOK WAS BORN IN THE BLACK, liquid darkness of an ancient river cave. During a kayaking expedition in 1983, an underwater tunnel in the center of Mexico’s Rio Urique swallowed me along with most of the raging river that brought me to it. As I entered what I thought would be my watery tomb, I suddenly relaxed into a consciousness that filled me with peace and clarity. When I finally emerged into the light of day, something awakened in me a primal awareness that apparently had been coddled to sleep by my so-called civilized perceptions.

For fourteen years, this awakening led me through a variety of adventures and explorations that eventually added reason to the intuitive insights I gleaned that day on the river, insights that changed my life forever. These illuminations came mostly from experiences with wild horses, trauma victims, Raramuri Indians, especially a one-hundred-year-old Raramuri shaman named Augustin Ramos, and academic research. Each served to help unfold a model of how- the human mind innately responds to life’s major influences, how- it can instinctively judge the merit of these influences, and how our awareness of this process ultimately determines whether or not we are able to live in accord with life’s universal harmony.

The formula I offer to describe this natural w-ay to harmonious living is a simplification. I say this as a warning, for oversimplification and dogma are the twin enemies of creative thought. A model, however, is only problematic if we use it as a substitute for the world of experience rather than as a guide to it. I hope that an awareness of what I refer to as the CAT-FAWN connection will throw us back into ourselves and our inborn connection with all things, preventing our destructive behavior and putting us back on course quickly if we stray too far from an enlightened path.

The concepts represented by the CAT-FAWN connection offer western minds a paradigm for understanding subjective experience, rather than for measuring objective reality. They symbolize the associations that have patterned the thinking styles of many indigenous people, especially Native Americans. I refer not so much to the conclusions of such thinking with which many of us are familiar but to their source. We already know that many primal cultures think differently about life’s interconnections than we generally do. We have not realized, however, that there is a primordial awareness behind such thinking that is a natural heritage for us all.

Whoever has maintained this awareness throughout history, regardless of skin color or religious faith, has managed to do a better job of preventing disharmonious relationships from dominating life and its structures. As a group, primal people have had more success with such management because, for them, harmony is mandatory in all spheres of life as a condition of Nature itself. Native American philosopher Jamake Highwater believes that harmony is “the resonance of a kind of sanity that predates psychology.”[1] Primal people therefore offer a living model for rediscovering our own innate primal awareness. With this awareness, the wonderful and diverse thinking styles represented within “western” and “primal” cultures can collaboratively produce complementary, holistic philosophies that may lead to health and vitality for Earth and its inhabitants.

This book is divided into two parts. The first part tells the true story of how I came to know of the CAT-FAWN connection through my newfound abilities to talk heart-to-heart with wild horses, trauma victims, troubled teenagers, and Raramuri shamans. The second part presents this mnemonic in detail and explores how and why it represents the process by which we all learn how to live, for better or worse.

The last quotation at the beginning of each chapter is from Augustin Ramos, the shaman with whom I lived in Copper Canyon. I have done my best to accurately translate his statements, but I have paraphrased on occasion where English words fail to capture his meaning.

Royalties from this book go to the Sierra Madre Alliance on behalf of the Raramuri simarones, North America’s most primal Native Americans, and their vanishing wilderness.

Part 1: Adventures and Explorations

Into the Heart

The passage through the magical threshold is a transit into a sphere of rebirth. The hero, instead of conquering or conciliating the power of the threshold, is swallowed into the unknown, and would appear to have died.

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces

There are places that have great power, like the entrance of a cave or the edge of a canyon. If you are there and you concentrate, you might learn to do many things you could not do before.

Augustin Ramos

MY JOURNEY TOWARD PRIMAL AWARENESS began on a cold, rainy day in February 1983. Dave Carr and I were working a twenty-four-hour shift as firefighters in a two-man engine company located atop Mount Tamalpais in Marin County, California. Emergency calls at our station were relatively few, and other firefighters often referred to it as the retirement valla with a view. A quiet assignment suited Dave and me, however. We were not anxious for someone to get hurt or for a house to burn down just so we could have some “action.” Besides, we got most of our excitement from white-water kayaking.

Four months had passed since we were on a river, and it would be three months longer before the spring runoffs were safe enough to kayak. This contributed to a craving for adventure that was at an all-time high for me, a craving I was never able to satisfy completely. When I got out of the Marine Corps in the early seventies, I tried to sail a small sloop from San Francisco to the Caribbean, but seasickness caused me to quit this otherwise exciting endeavor too soon. I then rode on horseback across the Pacific Crest trail, but unexpected snow put an early end to this effort as well. Now marriage and a full-time job seemed to preclude plans for exploits of such proportions.

On this particularly dreary February day, however, I felt desperate for such a wild undertaking. My marriage was on the rocks, and my job with the fire department was becoming intolerable. Of course, I was the common denominator in both problems, but I was too unaware to recognize this. Instead, I put the cause entirety outside of myself. For example, I blamed my wife for becoming too materialistic and sedentary, not realizing that my extreme and uncompromising expectations were partialty responsible for whatever truth there may have been in the allegation.

My fire service problems related to a book I had written exposing the fact that the lack of physical fitness among firefighters was the primary reason the profession was statistically the most hazardous occupation in the United States. Many of my peers thought I was implying they were unfit for their jobs. In fact, they were correct, and I was dispassionate with my criticisms and overly aggressive with my expectations. There was right and wTong, I thought, and I presumed to know- which was which, seeing no middle ground in my reasoned conclusions. This self-righteous attitude and my vehement defense of “the one logical truth” led me into many battles. I fell into a “me versus them” mentality and had a difficult time knowing whom I could trust. My hot temper and the militaristic impulses I picked up from Marine Corps training during the Vietnam catastrophe did not help matters. Nor did the frustration that seemed to come from the ways that these impulses contradicted my cynicism and antiwar sentiments.

The solution to my problems, I pretended to believe, w-as escape to some place remote and wild—even dangerous. But where? I no longer had a sailboat, so the ocean was not an option. The weather was too miserable for horse trekking, and I did not have enough funds for an exotic destination. On this particular stormy evening, Dave was repairing his bicycle in the fire station living room, and I was looking through Wild. Rivers of North America by Michael Jenkinson. Jenkinson recounted an unsuccessful attempt to paddle down the Rio Urique, which runs through the remote Copper Canyon area of central Mexico. He quit the trip because the water level was too low and the rocky- portages were ripping his party’s boats to shreds. Jenkinson recommended March as the best time to try the river, and here we were approaching March and already having more rainfall than had occurred during the year of Jenkinson’s expedition.[2]

In spite of its isolation, Copper Canyon was relatively close and inexpensive to reach. We owned inflatable kayaks that could be carried down into the canyon, and we each had accumulated more than a month’s worth of vacation. I had also heard about the amazing cardiovascular endurance of the Tarahumara Indians who lived in this region. The Tarahumara, who call themselves the Raramuri, commonly ran one-hundred mile races in the steep canyons with relative ease. In addition to my research interests in fitness, I was an endurance runner myself. The combination of an early season kayak trip and a chance to observe the Indian runners seemed perfect. I could not hide my enthusiasm as I told Dave about the idea. Anxious to begin the kayaking season with such an adventure, he agreed to join me.[3]

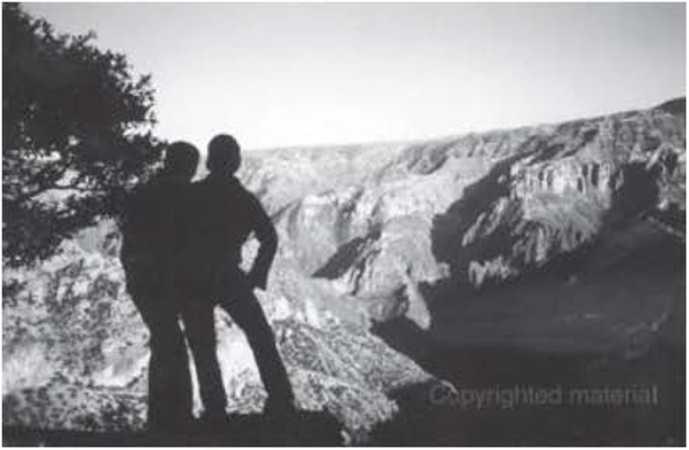

After making preparations, Dave and I took a plane to El Paso, a bus to Chihuahua, and then a train to El Divisidero, where a single hotel overlooked Copper Canyon at a place four times wider and two thousand feet deeper than the Grand Canyon. When I first looked at the maze of immense chasms, I wondered if we were being foolhardy and turned to Dave with raised eyebrows. He answered with a shrug of his shoulders. After a serious moment of reflection, we both laughed.

“Let’s find us a guide,” I suggested.

“I don’t think we could find the river otherwise,” Dave replied with a note of seriousness back in his voice.

Early the next morning Raramuri women arrived with wooden dolls, design work, drums, violins, and baskets woven from bear grass and pine needles. From caves and cabins hidden in the recesses of the great canyon, they had walked for many miles to sell these items to the tourists on the train. Luis, the native guide whom the hotel manager located for us, also arrived. He was about five feet tall, perhaps in his midtwenties. With his straw hat, red bandanna, western shirt, blue jeans, and belt, he looked to be a dark-skinned cowboy from Arizona. Not until we noticed his calloused brown feet, splayed out over the traditional Mexican sandals made from leather and automobile tires, did he seem “native.” We exchanged greetings, designed a makeshift backpack so he could earn some of our load, and started down into the canyon.

Our first stop was apparently Luis’s home. It was a small shack, built of stacked rocks with a wood shingle roof that allowed for a large exposed attic space, partially filled with ears of blue, yellow, and red corn. The hut’s small opening was doorless and from inside emerged a woman and two young girls, all wearing full skirts and blouses of colorful cloth. Each wore a patterned scarf on her head. Luis leaned down as his wife spoke in whispers to him. The youngest child riveted her eyes on Dave and me while we waited politely about twenty feet away. Then they disappeared back into the darkness of their house.

We drank from a nearby spring, covered by slabs of rock to keep animals out of it, and continued down the gradual slopes of the ridge until the trail turned into an almost vertical pitch of rock outcroppings and loose stones. Luis stopped, took off his sandals, and proceeded downhill. In spite of the jagged rocks, he showed no sign of discomfort, nor did he grimace at the narrow nylon straps digging into his shoulders under the weight of his pack. Barefooted, he seemed to glide down the cliffs, while we stumbled treacherously in our expensive hiking boots, constantly adjusting our high-tech backpacks to ease the weight of our gear, boats, and paddles. Dave and I could not guess why Luis had taken off his sandals, and we exchanged glances of disbelief.

Luis spoke his native Raramuri language with a spattering of Spanish. His comments made sense to us only in the context of our surroundings. For example, if he said something while pointing to a spring, we assumed he meant, “Here is some water to drink.” Of course, he might have told us, “The water is poisonous,” but we felt content with our interpretations and replied enthusiastically with sign language. By the time we were halfway down the canyon that led to the river, Dave, Luis, and I seemed like old friends.

After stopping for a bite to eat, I gave Luis a small harmonica as a gift. He put it in his pocket without a response. Sharing or korima is such a natural part of Raramuri life it requires no special expression of emotion. When we were finished eating, Luis took us off the trail and over a rocky ledge, obviously going out of our way. In a short while, he pointed to a huge boulder covered with large patches of orange, green, and yellow- lichens. The boulder was surrounded by a variety of plant life, taller and denser than what w-as common to the area. Like a child telling a secret, Luis motioned for us to tap on the rock.

Dave and I both rapped our knuckles softly on the rock. Although it looked like a rock and felt like a rock, it did not sound like one. Knocking on it caused a sound that in our estimation could only have been created by a large, hollow-, metal container. When we expressed our confusion to Luis, he shrugged his shoulders. We were not sure if this meant he had no answer to explain the phenomenon or if he did not know how- to describe it to people who could not speak his language. Not until fourteen years later, during my return to the canyon, would I learn the secret behind rocks such as this one—a secret the Raramuri believe is sacred.

After nearly ten hours of intense hiking, we arrived at the river. It was flowing at about twelve hundred cubic feet per second, a relatively safe flow for our remote situation. Luis watched with intense curiosity as we inflated our yellow kayaks. He obviously could not imagine anyone purposely entering the churning rapids. Luis blew nervously into the harmonica and watched us without interruption until we were ready to launch. We offered the traditional farewell, a gentle touching of one’s first three fingers to the other’s, and said, “Aripiche-ba,” Raramuri for “until we meet again.” Dave and I slid the boats into the water less than fifty feet above the first rapids. After successfully negotiating the first drop, I looked back to see Luis heading up the canyon.

For the remainder of the day, we rejoiced in the thrills of the rapids and in the beauty of the canyon. During flat stretches of water, however, I had the eerie feeling we were being watched. I felt the blood of my Cherokee heritage surge with the awareness that primal people were observing us. That night, as we camped under a canopy of stars, I dreamed that I was one of the Indians watching two white men paddling the river.

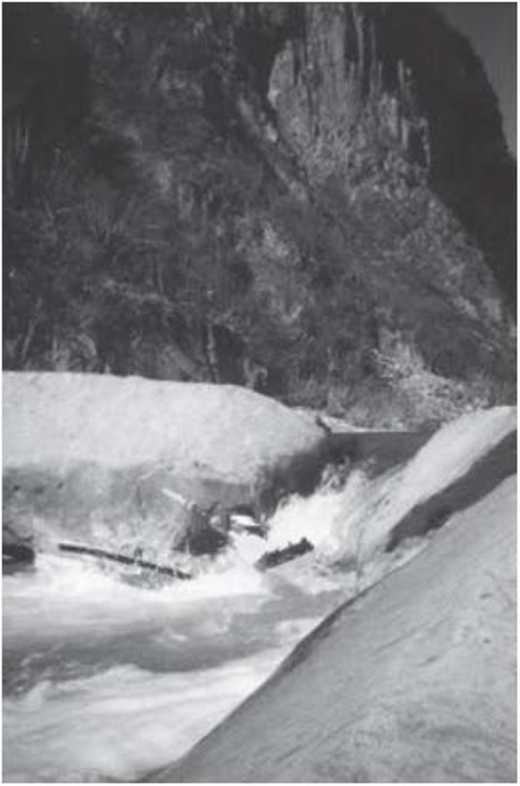

The next morning we pushed off from shore as soon as the sun made its way into the canyon. We were elated that the river was high enough to paddle, yet slow enough to navigate safely, allowing us enough time to scout each potentially dangerous drop. We did have to portage over rocks a few- times, and during one difficult climb over a maze of rocks, I yelled to Dave over the roar of the rapids that it would be perfect if only we had another foot of water. Within minutes clouds began to form. In an hour rain rapidly turned the sparkling clear water into a maelstrom of brown and white frothy energy. Increasingly, waterfalls cascaded down both sides of the canyon from creeks and crevices, giving a new perspective to the upthrust tilting of the rocks and the great volcanic sheets of vertical frozen lava. The raging river now- confirmed Jenkinson’s description. He had written in his journal, “In high water, the Urique may be the most violent river in America. During the rainy season, some Urique rapids seem like science fiction.”[4]

We stopped to put on rain gear. Within minutes the rock we had hauled our boats on was submerged. The increasing flow of the river and the difficulty of the rapids was beginning to exceed our skills. Searching for a place to safely exit the rising water, we rode the white waves into a narrow, mysterious canyon. Before us granite walls soared straight up on either side of the twisting river. Gray mist rose to meet the falling rain and glistened in the broken rays of the sun. Gigantic black, red, and white boulders stretched from one sheer wall to the other. The rocks were so crowded that the river all but disappeared through a labyrinth of cracks and deep tunnels. Jenkinson’s party had painstakingly portaged their boats around this section and wrote of this area, “There is no way anyone will ever run this rockfall in any level of water.”[5]

Jenkinson’s words proved true. It was my turn to lead, and Dave waited behind until I could reconnoiter. Too cold and anxious to follow our normal procedure of climbing a rock to scout what was ahead, I instead dropped into what appeared to be a quiet pool above the next set of rapids. As soon as I reached the pool, I realized that it merely feigned tranquillity. The whole river was backed up, patiently waiting to empty itself into a drain no more than two feet wide at the base of a huge boulder!

I desperately paddled upstream but kept getting pulled closer and closer to the hole that was swallowing sticks and leaves like a hungry beast. Fatigue soon overtook me, and my boat slammed into the hole, lodging halfway in, up to where the boat was too wide to enter. Perhaps it is not my time to go, I thought. I turned around and placed my hands on the huge rock wall in front of me, trying to balance myself amid the turbulent waves passing under and over the boat. While holding on to the rock wall for several minutes, I searched for ways to escape what I thought would be certain death in the hole.

Strangely, in spite of the chilling rain, the rock warmed my hands. Suddenly, a mysterious calm overcame me. A heightened sense of awareness propelled me into a multidimensional universe. Fear itself became a vibratory sensation that brought forth colors of perception words cannot describe. Confidence filled me. I continued searching for a way to survive, but something was telling me that what was about to happen was important and that I should not fear it.

These feelings pulsed through me like a current of electricity being emitted from the rock. Then I looked up and saw a chance for survival. A piece of driftwood from a previous flood was lodged in a hole in the rock several feet above my head. If I could reach it, I could climb to safety. As I stood to grab the log, however, a violent wave suddenly flipped my boat, and I disappeared into the cold, wet darkness of the hole.

When I went under, there was no doubt in my mind that I would drown, but instinctively I held my breath. The remarkable feeling of calm and peace came over me again. My entire life passed before me in a series of snapshots. With each one, I sent out loving thoughts to the characters and experiences they depicted. I embraced my family and friends. I prayed for Dave’s survival and safe return home. Although my eyes were closed, I sensed a radiant white glow of energy swirling about me. For a moment I thought I heard voices echoing an indescribable musical pattern of harmonies and rhythms. Then, just as I was out of air and about to drink the river into my lungs, the tunnel spit me out into the hazy daylight.

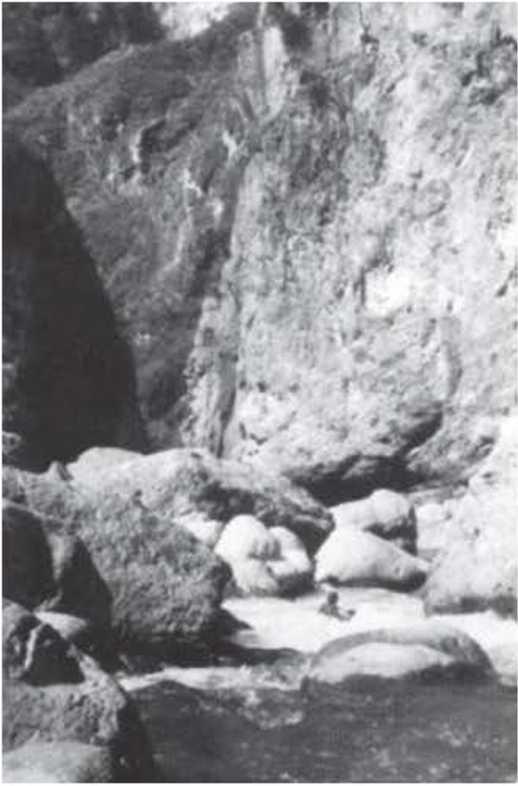

Knowing I had come out on the other side of the rock boulder, I scrambled to grab hold of a jagged rock and pulled my-self out of the rising water to avoid being swept downstream. Somehow negotiating the sheer canyon wall, Dave had managed to drag his boat along the river’s edge until he reached the other side of the large rock wall through which the tunnel ran. Without speaking, we climbed to the top of the great boulder. Dave lowered me down so I could reach my boat, which was still stuck at the entrance of the hole. I punctured each pontoon with a pocketknife and Dave pulled me back up to the safety of the ledge. We waited. Finally, the boat and its secured contents passed through the tunnel as I had. Still not saying a word, we patched it, blew it up, and forged downstream in search of a safe haven. Fortunately, around the next bend we came upon a large cave that was cut into a steep, grassy wall to the right of the river. We were more than thankful, for the river was now running at least six thousand cubic feet per second, and it was doubtful we would have survived the next set of rapids.

For three days Dave and I waited for the rains to subside. The cave sparkled with swirls of quartz under the glow of occasional rays of sun streaking through an opening high above us. Each evening the flooding river forced us to climb higher and higher in the cave. When we reached the highest ledge, we looked down. It seemed we were trapped by the water filling the entry.

On the third evening, the rain ended and the river stopped rising, but still trapped, we could not leave our perch. Early the next morning, before the sun’s rays pierced the darkness of the cave, I was awakened by a subtle awareness that we were not alone. I felt a presence looming in the dark recesses behind us. My eyes opened wide and my breath stopped as a large feline creature, barely visible in the luminescent light, walked heavily alongside my sleeping bag. The movements of the animal’s feet tugged gently on my bag. After passing me, it walked past Dave and disappeared around a corner at the end of the ledge. I knew Dave was awake also. I felt his breathless silence.

Whispering I asked, “Did you see what I saw?” Dave did not reply but reached slowly for his flashlight, scanning the walls with the dimming beam. We began to laugh hysterically.

“No one’s going to believe this,” Dave said.

“What else can happen?” I wondered out loud. Our abdominal muscles ached from laughing. We then fell sound asleep, as though the entire event had been a dream.

The next morning revealed the opening that led out of the cave. We examined the rock ledge for tracks but were not skillful enough to know whether the slight indentations in the leaves and twigs meant anything. They were wide enough, however, to support our assumption that our cave-mate was a mountain lion. We would learn later that the cat was probably an onza, a rare subspecies of mountain lion known to roam this part of the Sierra, and one of eighty-five endangered or threatened species surviving in the Sierra Madre Occidental.

Our meeting with the creature quickly faded from our thoughts as the reality of our predicament sank in. We were low on food. Although the river was flat and brown, debris raced past the now submerged cave entrance, revealing the strength of the current. Realizing how deep we were in the remote barranca, and not knowing how many more canyons were between us and the train track somewhere above, I thought returning to the river was our only option. I was sure that we would starve or get lost if we tried to climb out.

Dave knew rivers better than I did and disagreed. He told me the river was flat in front of the cave because the rocks were covered, but reminded me that the river had risen nearly twenty-five feet. Dave supposed that downstream the boulders would be as large as others we had encountered and this, he contended, would create large rapids and “keeper holes” that would trap and circulate us indefinitely. I countered with the obvious dangers of becoming lost in the wilderness.

“Let’s walk downstream. I’ll show you,” Dave said as he patiently ignored my references to starvation in the mountains.

After an hour or so of strenuous side-hill hiking and climbing, we came to a sharp turn in the river. There, two hundred feet below us, lay Copper Canyon’s version of Niagara Falls. I conceded that we should try to hike out of the canyon, without my usual reluctance to admit I was wrong.

We inched our way through the jungle of the lower canyon until w-e stumbled on the ancient ruins of an Indian hut. Huge roots, six to twelve inches in diameter, were growing through the stacked rock walls. Trails led from the rock foundation in several directions, and the one we chose brought us to an impasse. We stopped abruptly at a black and gray granite cliff that plunged dramatically down a thousand feet into a ravine. We had traveled half the day, and now we would have to return to the ruins. Backtracking in contemplative silence, I wished someone could show us the way to the railroad line.

By now Dave and I knew we would need a guide if we were to find our way out of the canyon. Strangely, in spite of our remoteness, I felt sure we would find one. Just before nightfall, my hunch came true. Two young Raramuris appeared from nowhere. One was carrying a dead fawn whose only sign of injury was its bleeding hooves, which had somehow been worn down to raw tissue. (I later learned that it was common for Raramuri to run deer to death over the steep canyon terrain.)

Our eager friendliness and our need for help seemed to assuage their initial suspicions. Making sounds like a train, we expressed our desire to reach the tracks at the top of the barrancas. The young men pointed upward as if they understood and motioned for us to follow them. In a short while the one with the deer stopped and spoke a few words to his friend. He then left us, and the other young man beckoned us to follow him. Before continuing, I reached into my backpack, pulled out a white sweater, and gave it to the young man in gratitude. Without changing his expression, he led the way.

For the remainder of our arduous ascent, the young man, perhaps in his twenties and now wearing my sweater, appeared each morning at our campsite to point out our route. Often he stayed ahead of us, using his ax to mark trail. He brought us through villages and cornfields on plateaus that seemed like islands amid the sea of steep cliffs and false summits. The people in the villages were not surprised to see us but remained distant. The women were especially cautious, and they seemed to vanish as soon as we appeared. I had read that Raramuri women believed that “aliens” came into the deep canyon to lasso and rape them, but I did not know at the time that the belief was both historic and prophetic.

Our young guide stayed with us until he thought we could continue without him, then he left for wherever he had come from. We had been on a fairly obvious trail for several hours when we came to a large creek that was too deep to cross without swimming. It was late afternoon and the nights were getting colder. The thought of wet sleeping bags and possible hypothermia crept into my mind.

"There must be a way across,” I pondered. Suddenly an old man appeared on the other side, carrying a small sack and wearing the traditional Raramuri loin cloth. He set his bag down and, using a long stick to probe for an underwater bridge, crossed the creek with a joyful smile on his face. He walked over to me and said, “Quira-ba,” Raramuri for “hello,” with an outstretched hand showing three fingers. I returned the greeting, and he grasped my hand and led me to the crossing. Using the pole to keep us on the stone bridge, he took me across the river and then returned for Dave.

After the crossing, he opened his bag and offered us each a withered apple. We knew- this man must have walked a long way for these apples, so we took only a small one each, even though we were hungry enough to eat all of them on the spot. Remembering the red dress material we carried with us for just such an encounter, I quickly opened my- bag and gave him the cloth. He smiled, took the gift, and continued on his way. As he left, I sat and watched him until he disappeared out of sight.

“What are you looking at?” Dave asked me. “Let’s go.”

I shook my head slowly. “I was just watching the old man,” I replied. “Can you believe him giving us his food? Did you feel his, I don’t know-, his ... presence?”

Dave smiled and changed the subject. “Now that we’re here near fresh water, what do you say we bathe?”

Without answering, I stripped and rummaged around in my bag for my biodegradable soap. I walked into the cold water, but before I could lather up Dave stopped me, arguing that using the soap in the stream would pollute it for the natives below. “But it’s biodegradable,” I protested. Dave held his ground. Reluctantly, I washed away from the stream, rinsing with water from my canteen.

At first, I resented Dave’s position, pouting for a while as we continued hiking. Then, suddenly I smiled. Of course, Dave was right. Biodegradable or not, someone downstream would be drinking my dirty suds if I had followed my selfish desire. The thought of the old man came back into my mind, and I apologized to Dave. An apology was somewhat out of character for me, but now it felt as natural and easy as the water flowing downstream. A renewed instinct about the value of Dave’s view made letting go of my own position an easy matter.

Earlier in the day the old man responded to our ridiculous train noise by pointing toward distant gray cliffs. Dodging cactus and the needle-sharp spikes of maguey, the plant from which tequila is made, we stayed on what we thought was a trail only to once again come to a dead end. We had barely begun to worry when our Raramuri friend appeared again and motioned for us to come with him. We followed him until, just before nightfall, we reached a small hut in the middle of a large, flat area perhaps five acres in size and surrounded by the distant mountains. He indicated that we should sleep in the hut, pointed toward the clear sky, gestured that it would be cold, and then left us.

We spread our sleeping bags on the dirt floor of the cabin and fell quickly asleep, wondering why we were not sleeping under the stars. Several hours later I awoke itching painfully, realizing that our floor was a foot thick accumulation of sheep dung infested with fleas of some sort. For some reason, they selected me for their meal. “The hell with this,” I said aloud as I rose to go outside. Now awake enough to realize it was snowing heavily, I returned to my pallet and tried to cover myself against the attacking fleas. The pain was intense, and it seemed my whole body had been bitten. Then I thought of the old man again and relaxed into the discomfort, resolving not to be bothered by it. My pain and itching disappeared with this resolution, as though my mind had some increased power over my body, and I fell asleep peacefully.

In the morning six inches of snow covered the ground. We ate some granola and waited hopefully for our guide as we puzzled about wdiich direction to take from here. Before long the old man arrived and led us to a passage through an arroyo, then smiled at us and left again. As he walked away, I thought about the many miles he must be walking each day back and forth from his home to the various places where we were lost and wondered how he knew’ when we needed him. Although I w-as grateful, I was no longer amazed at his kindness. I w-as also beginning to feel a strong affinity with him. As we parted, for what I thought would be the last time, I started to call after him, but I stopped myself when I realized I did not know what I would say. Before I realized I hadn’t even asked his name, he was out of sight. I turned and headed up the hill, not knowing that one day, fourteen years later, we would meet again in a most mysterious manner.

That night we arrived, not at the train depot, but at a snow-covered mission. We nearly cried with disappointment when a padre told us the train station of San Rafael was thirty kilometers further. Exhausted, we sat on our packs and looked around. Although we had stubbornly carried our boats the entire way, we were now ready to abandon them rather than earn them another twenty plus miles. Fortunately, we found a man with a small horse whom we were able to hire to pack our gear and lead us to San Rafael.

The elderly mestizo tied our packs securely to a wooden saddle and then led us and the horse at a ten-minute-mile pace through snowy pines. Six hours later he brought us down a steep hill into the small town of San Rafael. I noted that he hid his large hunting knife in a bush outside of town, and we later learned that the Raramuri were not allowed to carry knives in San Rafael. Indians, knives, and alcohol were apparently a deadly combination, even for the tough Mexicans who lived here.

As soon as we arrived in the small town, we paid our guide and he disappeared. Almost immediately a group of five or six Mexicans gathered around us. One man excitedly took me by the arm and urged me to follow him. The others escorted Dave away in the opposite direction. After everything we went through, now we were going to be murdered, I thought.

The man led me to a small house, invited me inside, and told me to wait while he searched desperately for something in another room. In a few moments, he returned and showed me a small book written in Spanish. It was titled Rio Urique and the cover photo illustrated two small, round rubber rafts. Apparently this man knew the meaning of the boats strapped to our backpacks. He opened the book and pointed to a photo of a young man in one of the rafts, then pointed to himself. He had been in the first expedition that tried to navigate the Rio Urique, several years before the Jenkinson expedition.

Dave had been socializing with his new friends in the local saloon. By the time I joined him, a dozen bottles of beer and numerous shots of tequila had obviously been consumed. Enjoying the comradeship for as long as we could, we finally asked about a place to sleep. We were told there were no hotels, but an abandoned jail cell was available for a very small price. Laughing ourselves to sleep on two cots and surrounded by iron bars, Dave and I slept like the dead. The next morning we caught the train to Los Mochis where we recuperated for several days before returning home. We still had our boats.

We resumed our lives as professional firefighters. Dave had been reluctant to discuss my near death experience and remained so, although once he shared with me the foreboding feeling he felt when we first entered the canyon. I did not understand his silence but respected it. As for myself, things were not as they had been before I left. I had changed. I found myself to be more forgiving and more patient; reflection replaced reaction more often than before. My hard logic more readily made room for intuitive considerations, something I had seldom given much notice. I no longer thought of truth as something definite and unyielding but as something woven into both sides of an issue. These changes were not miraculous, and I often fell back into my old ways, but a new energy and a new direction took hold of me.

My outside pursuits and interests were also different. I began an intensive study of spontaneous hypnosis and began communicating differently with patients while on duty as a firefighter and emergency medical technician (EMT). I was able to speak to another part of their psyches, and through my directives, people were taking amazing control of their autonomic nervous systems. They were coming out of shock, stopping their bleeding, and controlling their blood pressure in response to my suggestions. Using the phenomenon on myself, I underwent deep abdominal surgery without anesthesia and participated in one of the first firewalking clinics in the country. During the next decade I continued discovering and using my new abilities. Although our relationship had improved significantly, my wife and I still had irreconcilable differences of opinion regarding lifestyles, so we peacefully divorced.

Shortly after my divorce, I met Beatrice, a free-spirited artist who loved to ride horses, and we spent much time riding through the redwoods in the Point Reyes wilderness. I felt more sensitive to my surroundings and started waiting articles about environmental issues, trying to avoid polemical rhetoric in the process. I even discovered I could “talk” with wild horses, a phenomenon that would have a significant influence on my life in itself and to which I have devoted the next chapter.

In addition to my new interests, attitudes, and communication skills, it seemed as if I could tune in to invisible realities and “read” energy from things I could not see. For example, once on a lonely drive from California to Idaho I was thinking of Wolf, a dear companion who was always at my side. He was half wolf and we used to dog-sled race together. Since his death I had missed him terribly and on this particular stretch of isolated road, somewhere in the middle of Nevada, I said to myself, I would love it if a small wolf puppy like Wolf appeared on the road. No sooner I had finished thinking this, than before me I saw such a creature. She was in the middle of the freeway and seemed to be lost. I pulled over, backed up, and called to her. Without hesitating, she ran to me, jumped in the back seat, and went to sleep. I inquired at the nearest humane society- and at the few ranches in the vicinity to see if anyone knew the animal, but no one had ever seen her before, so I brought her home. To this day she remains my companion and is similar to my original Wolf in many ways.

How I first came to live off the grid in the wilderness is another example. I wanted to live in a place with privacy and wilderness akin to that in Copper Canyon. I did not want to stray far from Marin County-, but where would I find wilderness less than an hour north of San Francisco? About to give up and move out of state, something told me to call an old friend I had not spoken to for several years.

“Hello, John. How are you? I quit the fire sen-ice and I’m leaving the state. I haven’t talked to you in ages and wanted to say good-bye.”

“Why are you leaving California?” he asked me.

After hearing my explanation, he said, “Hey, I’ll tell you what. I just bought four hundred beautiful acres—full of forests and lakes—right in the heart of Sonoma County. I need someone like you to help me develop it into a horse ranch. Why don’t you meet me there this afternoon and have a look before you commit to Washington?” The rest, as they say, is history. For years Bea and I lived on the land like Indians, leaving only after it became a sophisticated Arabian facility with paved roads and lights.

Of course, if these things happened just once in a while, I might have considered them coincidences. But they happened so frequently that they no longer surprised me. When I learned that equestrian endurance racing was going to be an Olympic sport, I did not have a suitable horse to train, but something told me that the entertainer Wayne Newton would furnish me with one. All I knew- about Wayne was that he owned expensive Arabians and that he was part Cherokee. I wrote him a letter, sharing with him my ow-n Cherokee heritage and describing my need for an endurance prospect. The next week his secretary- invited me to Los Vegas to choose the horse we wanted.

I also entered into a unique relationship with Becky London that defied convention. Becky, a gracious lady in her late seventies, was the surviving daughter of author Jack London. I had met her once before and knew she lived nearby. Acting on a compulsion that I did not comprehend, I looked her up in Glen Ellen, California, and invited her to go sailing with Bea and me. Becky had never been sailing before because her parents' divorce decree prohibited her father from taking his two daughters on such excursions, but she had nonetheless read the many stories her father wrote about sailing. In spite of a windy day on the San Francisco Bay, she w-as thrilled as the small sloop bounced and tilted in the waves. With the boat heeled over at an acute angle that would have frightened many first-timers, she recited the descriptions of rough weather sailing that her father had written in The Sea Wolf and in Tales of the Oyster Pirates.

During the years prior to her death, Becky joined us for many other such occasions. One day several weeks after our first sail together, Bea and I visited Becky in her small apartment in Glen Ellen. Spontaneously, I went into a trance and started saying things about Becky’s childhood that she said had never been recorded by London’s biographers! She was certain that no one but herself and her father could have known the anecdotes I related. On another occasion when Becky and I w-ere talking in her home and Bea was videotaping us, Becky- confessed that she believed that I was the “reincarnation of Daddy.” I did not subscribe fully to the usual definitions of reincarnation but felt I somehow connected with the earthbound energies of Jack London wiiile I was living in Alameda, an area he often frequented. Perhaps my desire to look up Becky and do with her the many things Jack had not been able to do was prompted by this energy.

I believed that these unusual experiences and my new feelings were associated with my Rio Urique adventure, but I could not explain how or why. Then several incidents happened in succession and offered some possible answers. The first was a visit with Lucy Stern, a student of ancient cultures, a longtime friend of Bea’s, and a woman gifted with clairvoyant insight.

One night I showed Lucy my slide show of the Rio Urique trip. After the presentation, Lucy- told me that she had lived with the Raramuri in Mexico for several months in 1966. A shaman, or ooru’ame, had taken her to a sacred cave and Lucy remembered walking through a thick mat of bat dung, which the Raramuri used to process lime. They crawled through a hole into a dark chamber. Lucy and the ooru’ame sat in the darkness, and the shaman told her about the ancient ways of Raramuri culture. The information he shared with her gave me goose bumps. According to the shaman, thousands of years ago individuals marked for the shaman path were tested in the deepest part of a narrow canyon through which a river ran. Candidates were brought to this narrow gorge where the walls stretched up vertically into the sky and giant boulders blocked the river's clear passage. Through one of the largest of these boulders existed a maze of tunnels. These tunnels were created over millennia when the main channel became blocked by driftwood. Water then worked its way out through other fissures and cracks. Before any of the new routes became large, the wood rotted and the main exit was once again clear. The result of this natural process of evolution was many dead-end caverns and a tunnel about two feet in diameter that passed through a giant boulder.

The shaman initiate would be pushed into the river just above the entry- to this underwater drainage during moderate to high water flows. According to the story, once in the tunnel, a struggling man or woman would be carried toward an exit too narrow for a body to fit through. The water would pin him or her against the end of this fissure until he or she drowned. One who did not struggle, however, would be carried by the slightly stronger current that led through the main tunnel. If a person emerged alive from the passage, he or she passed the test.

It did not seem as though there could have been another place in the entire Sierra Madre that fit the description of the gorge, boulders, and underground passage besides the place of my “accident.” If I had gone through the same tunnel, though, what did it mean? I wondered day and night about how the event might have been responsible for my new perspectives and abilities.

Other information brought me closer to answering these questions, beginning with the day in 1991 when I noticed a stranger riding a horse around one of the lakes on the Sonoma property. He told me his name was Sam Keen and that he was my neighbor. I introduced myself and invited him to come riding on the property- any time. By this time I had become well-known for my work with wild horses, and Sam said he had heard of me and was excited to have a neighbor with whom he could ride. At the time I did not know he was a best-selling author of numerous books on philosophy, consciousness, and mythology.

The next week, Sam invited me to his home one evening to hear his colleague Howard Teich, a psychologist and mythologist, talk about solar-lunar mythologies of ancient cultures. The symbols of the sun and moon depicted in the artwork of many indigenous cultures struck a chord deep within me. “The union of the same is a prerequisite for the union of the opposite,” Howard exclaimed, while pointing to a slide showing a stone sculpture of twins found in the ruins of a Mayan excavation. One was holding the moon and the other the sun. Beatrice and I looked at one another and nodded, intuitively comprehending the meaning. Howard was delighted that we seemed to understand what he was trying to say.

Intrigued by Howard’s research and feeling that it was connected to my experiences, I invited him to a showing of my Rio Urique slide show the following month. I briefly explained my mysterious journey and the changes in my life that evolved afterward. Recommending that I keep track of my dreams for several weeks, Howard said he had another series of slides he wanted to show me, but first he wanted to learn something about my dreams.

Curious about his odd but sincere prescription, I began trying to remember my dreams. I did not normally remember dreams and had trouble doing so during the following weeks. I was about to give up on the idea when I noticed a passage about vision quests in a book my wife had given me, Vision by Tom Brown. After reading it, I decided a vision quest might be a way for me to remember my dreams. The next day, carrying only a canteen of water, I followed the guidelines he described in the book, locating a remote area with few distractions and stowing my clothes and canteen out of sight.[6]

Fourteen hours later, half asleep and half awake, I had the most vivid dream of my life. I dreamed that I was fishing in the lake. Standing on the dock, I pulled in a large bass. The bass was covered with mud, so I proceeded to wash it off. As the mud disappeared, the fish began changing into a beautiful, magical dark-skinned child, aglow with a halo of light. The child took me gently by the hand and pulled me back into the lake. The lake then became a tropical ocean, with beautiful fish and coral in abundance. The child took me to a variety of places where people with whom I needed to heal or improve a relationship were waiting. He left me with each person just long enough for me to affect a positive resolution, and then came back to take me to the next one. Some of those I visited were dead, and I eventually awakened from my dream with tears streaming down my face. I looked around to be sure where I was. Morning was just breaking through the trees, and I felt the chill of the air for the first time on my naked skin. I hiked back to my home and called Howard.

Listening carefully to the details of my dream, Howard told me that Carl Jung believed that dreams of a fish illustrate unconscious knowledge of the individuation process that attempts to unite the conscious and unconscious. “All of this is quite fascinating. I think it is important for you to see my slides now of the Navajo sand paintings. Can you come to my office tomorrow night?” Howard spoke professionally, but he could not hide his excitement. I felt sure he saw me as a case study demonstrating a living representation of archetypal myths. Since I was beginning to think the same thing, I hastily accepted the invitation.

Howard’s slide show- of sand paintings depicted the Navajo story- “Where the Two Come to the Father.” It was about twin heroes and their journey- to obtain the tools they- needed to save their community from the monsters that threatened it. One twin was named Monster Slayer. Known for his aggressive, goal-oriented, logical traits, Monster Slayer reminded me of my-self, especialty of how I had been prior to the Copper Cany-on adventure. Monster Slayer’s twin embodied more mysterious qualities; he was reflective, passive, intuitive, and hypnotic. These were the characteristics I had begun to express since my journey into Raramuri land. Then, with some suspense, Howard told me the name of the second twin. He was called Child Born of the Water. Memories of both my emergence from the watery womb of the Urique and my dream of the w-ater-child chilled me to the bone.

Such insights continued to bombard me. Soon after Howard’s presentation, Sam invited Bea and me to a special showing of a film about his friend and mentor, Joseph Campbell. I was intrigued with Campbell’s references to myths, and the next day I bought a copy of The Hero with a Thousand Faces, one of Campbell’s most famous works. I brought the book home, opened to page thirty, and read: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder. Fabulous forces are there encountered and a victory is won. The hero comes back from his mysterious adventure with the power to bestow- boons on his fellow man.”[7]

If such myths were representations of archetypal truths buried in the human psyche as Campbell claimed, it would seem natural that life experiences could express them. My emergence from the ritual boulder in the Rio Urique may have been the symbolic birth of my own repressed “twin.” I was also struck by Campbell’s claim that the purpose of the “hero’s” adventures was ultimately to “bestow boons on his fellow man.” Since my return from Mexico, I felt more strongly about wanting to help others than ever before. In fact, several weeks after Howard’s slide show about the Navajo twins, another vivid dream hinted at a way I could possibly make such a contribution.

I dreamed about the mountain lion who walked over my sleeping bag that night in the cave and the fawn I saw being carried by the young Raramuri when Dave and I first began our climb out of Copper Canyon. In the dream, the fawn came to life while still on the shoulders of the Indian and jumped onto the back of the mountain lion. The mountain lion twisted and bucked until it finally threw the fawn high into the air, where it hovered like an angel while the great cat watched intently, concentrating on every move the fawn would make. Then, the letters C, A, T, and F, A, W, and TV, flashed before me like neon signs.

Waking peacefully I reached for a pencil and scrap of paper and jotted down the initials, CAT and FAWN. I knew as I was writing the letters down that they signified something important. Intuitively, I believed that the symbology of the animals and their relationship to one another, as well as some idea represented by the letters, would explain the changes in my life. More importantly, I felt this concept was a key to the doors of understanding that could lead to harmonious relationships in a world disintegrating into disharmony. Perhaps it would be the “boon to my fellow man” that Campbell had mentioned.

I would not feel certain about the meaning of either the dream or the initials for years, although I experimented often with different possibilities. For example, I inserted Consciousness and Teaching, or Caring Attitude Today, and many other options for CAT. I tried writing Fellowship, Action, Wisdom, and Nurturing for FAWN. However, none of these words resonated in me as being what my dream had intended. Further experiences using my new insights would prove to be necessary before I could fully realize the intended message of the two animals that had visited. One group of such experiences involved another animal, the wild horse, as well as an equally spirited creature, the troubled teenager.

Wild Spirits

When the West wind brings the spirit of horse into your life it is to remind you that the Natural Way has not been lost.

Navajo philosopher in Equus, by Robert Vaura

You wonder why you feel good when you touch us, lean into us, ride us. It is because we connect you to the stars. We are here to serve as mirrors so that you can find your way back to that Source that serves for us all.

Linda Tellington Jones. An Introduction to the Telling ton-Jones Equine Awareness Method

The young people are like the four-legged ones. They sense a secret greatness in themselves that seeks expression. They know they are entwined with the wildness. It is our job not to interfere with their wisdom about this.

Augustin Ramos

IN MY EARLY CHILDHOOD, I saw no clear line between heroes and horses. Hopalong Cassidy and Topper were embroidered on my bedspreads. A portrait of Roy Rogers and Trigger hung on my wall. A plastic replica of the Lone Ranger’s horse, Silver, sat on my desk next to a lamp made out of a wooden stirrup. On Saturday mornings I watched Fury and My Friend Flicka on television, and I never doubted that their masters communicated v\dth them in some secret code, a code that was revealed to me after my experience on the Rio Urique!

Except for a small stint at a rodeo, I spent most of my life in the absence of real horses until I was introduced to endurance riding and ride-and-tie racing at the age of thirty-one, about six years prior to my trip to the Rio Urique. The former involves racing a horse over a one- hundred-mile course. The latter is an event where two people take turns riding a horse, one riding ahead while the other runs, until the horse is tied and an exchange is made. This leapfrogging continues until the entire team crosses the finish line, usually forty- miles from the start. Both events required horsemanship, but neither had resulted in my communicating with horses at any sort of mystical level. Soon after my return from Copper Canyon, however, I discovered an ability’ to talk to wild horses that was so remarkable it was eventually covered on national television and in almost every equestrian magazine in the country. I first discovered this phenomenon with a mustang named Corazon.

The Arabian breed dominated endurance riding and ride-and-tie racing, but a year before the Copper Canyon trip I brought home a mustang to do the job. I thought this animal’s natural toughness would be an advantage in my chosen equestrian sports. I suppose I also wanted to be different. Besides, the mustangs were losing ground on the open range to cattle interests, and I thought endurance racing might provide a use for those being rounded up for adoption.

The horse I brought home was twelve years old, although I was told he was only six. I purchased him from a man who had adopted the horse from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in Susanville, California. Warning me that my new charge was unruly, he assured me the horse could be trained. I paid meat-market rates, getting the big black animal for two hundred dollars. I named him Corazon because he seemed to have a great deal of heart, considering all he had gone through.

Corazon was indeed a handful. I could barely catch him, let alone mount him. In time, however, I figured out a way to do both. I took to throwing a long rope around his neck to catch him. Then, using a technique known as sidelining, I lifted his rear leg off the ground, forcing him to stand still until I was safely aboard. Once in the saddle I would untie the rope, let his leg down, and hold on for dear life.

Corazon remained a relatively unpredictable animal, and I planned to let him go after returning from Mexico. When I got back, however, my relationship with him took a new turn. Even though I had not seen Corazon in more than a month, the first time I walked out to catch him he did not run away, nor did I feel my usual anxiety- and frustration. I walked toward him and patiently called his name. To my delight, he stepped up to me and let me put the halter on him. Maintaining the rapport, I saddled him, climbed aboard, and had a pleasantly uneventful ride for the first time in our career together.

Prior to my Copper Canyon experience Corazon had not been very responsive to my aggressive training efforts, but I had managed to ride him in one major competition called the Tevis Cup, considered the toughest hundred-mile event in the country. Although he got away from me several times, kicking several competitors and their mounts before the seventeen- hour race was over, we finished in first place. Because no one could nail shoes on him, he also became the first and only horse in the history- of the event to complete the course barefooted.

After Mexico, Corazon and I rode the endurance circuit for the next year or so. Although he was not fast enough to win many races, we always placed in the top ten. Our mutual trust was such that one summer I campaigned him without a headstall, directing him only with mental commands. It seemed a crazy thing to do, but I was enjoying testing what seemed to be a telepathic link between the two of us. I was also haying fun with my fellow Arabian owmers, watching their reactions when this big-headed creature that looked like a draft horse outdistanced their mounts and did it without reins! By the end of summer, Corazon had become a mini-legend in the endurance w-orld, and our amazing bond grew- steadily.

One March night in 1984, exactly a year after my return from the Rio Urique expedition, this bond seemed mystical. It had been raining all week and this night was no exception. I heard something banging out back in the area of the horse corral but dismissed it as merely the stormy weather. I started to fall asleep again when suddenly my eyes opened wide. The noise had stopped but I felt something was wrong. I dressed, put on a rain poncho, and grabbed a flashlight. I walked through the pouring rain to the edge of the corral and scanned the area.

I saw Corazon standing under the shed roof, but something looked strange. Upon closer examination I saw that his head was protruding through a newly torn hole in the shed wall. Intermittently he would try to run forward as though he wished to pass through the wall entirely. I hurried back to the house and slipped on my rubber boots for the corral had turned into a lake of mud. When I returned Corazon was lunging violently against the wall. I managed to get a rope around his neck and with some effort succeeded in pulling his head out of the hole. Freed from his self-made trap, he plunged into the night, dragging me behind.

Near the shed was a large post for training purposes. It stood solid and strong in spite of the mud. I managed to catch several turns around it with the long lead rope as Corazon ran in mad circles around it. In a few- minutes the rope was too short for him to move. I shined the light in his fiendish eyes, and he stared straight through me. I felt his fear, however, as if we both shared the same horrible apprehension. I ran back into the house to call my friend and horse veterinarian, Myron Hinrichs.

Myron accepted my emergency call with his usual professional demeanor, and an hour later I met him by the road in front of my house. I loaned him a pair of tall mud boots and guided him to the post that held Corazon. The rain had stopped and a strange dawn appeared as we trudged our way through the mud. I explained what happened and Myron looked into the mustang’s eyes. It did not take long for him to determine that the animal’s brain was all but gone. He diagnosed the problem as Walla Walla Walking Disease and said Corazon had probably eaten a poisonous plant in the desolate range from wiiich he came. The disease had been slowly killing him for years. All this time his tremendous spirit and strength disguised a gradually deteriorating liver. There was no choice but to put him down.

It began to rain again as Myron filled a syringe with twenty cubic centimeters of tripelennamine. I started to cry and my tears mixed with the rain, washing the specks of mud from my face. Myron emptied the deadly fluid into Corazon. He assured me the dose was sufficient to kill an elephant and that Corazon w-ould feel no pain. The great animal’s body jerked briefly, then went limp. Myron took out his pocketknife, cut the rope that was holding the horse’s body awkwardly against the post, and Corazon fell lifelessly to the ground.

Myron’s first words expressed a practical concern regarding having a dead horse in my muddy corral in the middle of winter. The gate to the paved road was more than three hundred feet away, and it would be months before the terrain would dry sufficiently for a tallow truck to pick up the body. This realization sobered my sadness, and I pondered the predicament but could think of no immediate solution. I dropped to my knees in the mud, patted Corazon on

the shoulder and said quietly, “Old buddy, if only you could have made it to the road.”

Suddenly Corazon rose to his feet and charged through the muddy field as only a horse with his large hooves could do. He ran straight for the aluminum gate that opened onto the paved road. Without stopping, he crashed into the gate and then fell squarely on the pavement, never to move again.

To this day Myron swears that what Corazon did was impossible.

Corazon had lived most of his captive life in a constant state of fear, continually struggling against the things that frightened him—including me. When I returned from Copper Canyon, however, he looked to me for support during such times, as though my changed mind-set somehow inspired confidence in him. Rather than separating us, his fear offered us an opportunity to concentrate on a shared ability to cooperate on a nonverbal level that we could both access. Instead of letting his fear create a fear response in me, I used fear to stimulate intuitive insights, whereas before it seemed to block them.

I thought often about what I had done differently with Corazon after the incident on the Rio Urique. Maybe, I thought, I learned to appreciate how much fear affected Corazon. My previous horses were not frightened of me, nor I of them, so dealing with fear in the presence of horses was a new consideration for me. I wondered if I merely became more sensitive to this emotion after facing my own fear in the underwater tunnel.

One evening while thinking about all of this, I suddenly stepped back twenty years in time as I remembered an occasion when I had been frightened by a horse. I recalled that there was a brief moment when the horse and I connected at a level similar to what I experienced with Corazon. It happened when I was thrown from a bucking horse in my first rodeo.

The notion to ride a bronco originated on a warm, humid Missouri evening in June while several friends and I were spending a typical Saturday night parked in my 1955 Chevrolet at the local Steak and Shake. We were eating hamburgers and waiting for someone to discover something else to do. All but one of us were juniors and members of the high school wrestling team. The exception was a tall, lanky boy named Leroy. He had recently moved to St. Louis from a small town in Texas where he competed in the rodeo. Leroy looked and talked like a cowboy, and his manner revealed a mild protest and timid frankness that won me to him instantly. I was surprised when he dared me to ride in a rodeo with him to prove that bronco riding was tougher than wrestling.

“No problem. Let’s bring dates,” I replied, exuding the same machismo that probably inspired Leroy’s challenge. My confidence, however, came mostly from not believing there was really a forthcoming rodeo nearby that we would be able to enter.

I was mistaken. The following weekend, a five-hour drive brought us to the outskirts of a small town and a large banner stating simply: “Rodeo Today.” When we pulled into the rodeo grounds, a dirt parking lot and some dilapidated wooden bleachers at least let me know I was not starting out in the big times. Our girlfriends broke out the sandwiches and soda while Leroy and I went to pay our entry fees for the bareback riding event. Borrowed cowboy boots, two sizes too large and stuffed with newspapers, along with a newly purchased straw cowboy hat helped me feel the part until I heard one of the competitors ask Leroy who the “greenhorn” was.

On the drive from St. Louis, Leroy had told a story about a huge seventeen-hand-tall horse with a glass eye. His name was Old Number Seven. The animal was “one of Tommy Steiner’s best bucking horses,” according to Leroy, and it had never been ridden for the eight seconds necessary to qualify for points. Old Number Seven was “mean as a bull” and Leroy assured me he was one bronco I would never want to meet. I did not plan on meeting this horse and, in fact, did not pay too much attention to the story about him. I finally managed to hold hands with the girl I was trying to impress with my rodeo adventure and was thinking more about this accomplishment than about some horse in Texas.

The horse a contestant would ride was determined by a number he pulled out of a hat. The luck of the draw had much to do with the outcome of a bucking competition. If you drew a good bucking horse, you were likely to get more points. When it was my turn, I pulled out a folded piece of paper and nonchalantly opened it. The number seven was scribbled over the middle of the crease in the paper. At first, the number made no sense. I assumed that each of the horses had been assigned a different number and that I would learn the horse’s name eventually. Waiting for Leroy’s turn to draw, I showed him my slip of paper and whispered jokingly, “Hey Leroy, is my horse related to your Old Number Seven?”

The look of genuine concern that showed on his face startled me so much I barely heard him say, “That is Old Number Seven.” I did not know if he was kidding me until a moment later when he drew his paper from the hat and handed it to me. “Whiskey” was written on it with no number. My heart rate, already elevated to precompetition status, immediately jumped four gears to the speed and pitch of a jackhammer.

At that point, the cowboy who earlier referred to me as “the greenhorn” handed me a withered green apple. “You’d better try to make friends with that one, son, before you get on his back. He’s in chute number three.”

It made sense to me at the time, so I took the apple and climbed to the top of the third pen where some men were trying to urge a giant bay horse forward a few steps so they could close the gate behind him. One of them carefully positioned himself so he could kick the horse in the rump with both boots while balancing on the rails. As he did so, Old Number Seven jumped forward, reared, then lowered his head down and slammed his rear hooves into the gate that was closing behind him. “Good thing he’s not shod,” someone remarked, “or he’d have put his legs right through.”

I told the man nearest me that I would be riding “the big guy.” I said it as matter-of-factly as my shaky voice would allow. Then I reached down into the chute to offer the apple to the animal in a sincere effort to make friends with him. “I wouldn’t get your hand in there if I were you,” the same man suggested. Below me the other cowboys, led by the one who had given me the apple, were laughing mercilessly. I realized I had been set up but imagined that every first-timer was so initiated. I dropped the apple to the ground and nervously put on a pair of spurs while Leroy placed the bareback rig on the horse for me.

When it was my turn, I heard someone with a megaphone say something about “chute three” and “a young man from the city” and “his first ride on one of the toughest horses around” and finally “Old Number Seven.” Standing on the rail boards on both sides of the chute with my crotch inches away from the brownish gray fur of the horse, I gripped the handle of the bucking rig tightly and eased myself onto Old Number Seven’s back. I felt the warmth of the explosive creature beneath me and realized I had never been so frightened. As soon as the gate opened, however, I entered into a state of concentration that brought me into complete harmony with the bucking beast.

The bronco jumped straight up into the air and literally spun his way out of the chute. As he bucked in place, I began “yehahing” and felt in synch with every move the animal made. In a few seconds, he stopped bucking and went into a flat run toward the opposite end of the arena. He was unbelievably fast, and I speculated what my fate would be when he reached the fence and bleachers on the other side. Suddenly, the horse’s front legs straightened and stopped dead in their tracks while his rear-end continued moving forward and upward.

I lurched forward until Old Number Seven’s good eye stared up at me, only inches away from mine. I gripped the rig with both hands, using all my strength to keep from flying over the horse’s head. Pulling myself down and back I managed to return to my seat. Then I heard the eight-second buzzer ring.

Not knowing that I had disqualified myself by holding on with both hands, I thought I had become the first person to ride Old Number Seven to the buzzer. The horse was bucking more easily now, with a rhythm that allowed me to focus on my perceived triumph. Unconcerned with how I was going to get back on the ground, I was already looking forward to the ride home in the backseat with my new girlfriend. Then, just as the pickup rider came alongside to release the bucking strap, Old Number Seven, knowing my mind was elsewhere, threw one hard buck and tossed me head over heels into the dirt.

Barely aware of pulled groin muscles and a strained back, I picked up my hat, slapped the dust off it (as I had seen cowboys do on TV), placed it on my head, and walked the proudest walk of my young life toward the stands. As I approached the small crowd, I realized that people were laughing at me. Where was the applause for being the first person to ride out the glasseyed legend? Leroy was pointing at me and laughing so hard that he nearly fell off the fence. What a sight I was to behold! My face and teeth were caked with dirt and manure. My straw hat, having been stomped on by the horse, was balanced precariously on my head. One oversized boot was turned out at a ninety-degree angle as I strutted unaware.

“What’s wrong with you guys?” I asked my friends angrily, oblivious to everything save the need to regain my hero’s image. Just then, Old Number Seven, still being chased by the amateur pick-up rider, ran past me and let go a side kick that caught me squarely in the behind. More to escape than from the impact, I dove to the ground. Lying there in the dust, I looked up at the horse as he ran past me. He turned his head back toward me and, for an eternal moment, we looked at one another. Suddenly, I was overwhelmed with a profound but undefinable realization. I began laughing loudly and genuinely. My friends, relieved I was not hurt, helped me to my feet and soon joined me in my unrestrained laughter. Besides sore muscles and throbbing buttocks, all I felt was love for life and everything in it. I sensed the horse had given me more than just a swift kick in the pants. I was not aware enough at the time to know it, but during that moment of concentration Old Number Seven had conveyed a message that I understood only at the deepest level of my consciousness.

In retrospect, I can’t be certain that Old Number Seven really spoke to me, and yet when we looked at one another something special occurred that transformed my fear into joy. As I reflected on the memory, I considered the possibility that my fear made me receptive to the animal’s telepathic communication in the same way Corazon’s fear made him receptive to mine. I was beginning to believe that the concept of fear was part of the CAT-FAWN mnemonic.

With this thought in mind, I continued gentling wild horses for myself and others, noticing that I could enter into a special dialogue with the animals when they were stressed. I suspected that their fear made them extremely receptive to my thoughts, but only if my thoughts were at the right “frequency.” If my concentration had a sufficient amount of empathy, trust, strength, confidence, love, and sense of “oneness,” I could enter into some common consciousness that the animal and I shared.