Margo Note

Monster-Making

Narrative/Metanarrative in the Representation of Aileen Wuornos

America’s First Female Serial Killer?

Aileen Wuornos’s Life and Crimes

Wuornos’s Representation as White Trash

Wuornos’s Representation as a Prostitute

Wuornos’s Representation as a Lesbian

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank:

Lyde Sizer, my thesis advisor, who pushed me to work and think harder

Priscilla Murolo, my second reader, who reminded me of the importance of structure

Tara James and my thesis workshop peers Gamp, Katarina Parker, and Artie Philie for editing and advising Bill Florio for support

Lisa Dugan, author of Sapphic Slashers: Sex, Violence, and American Modernity, a work that inspired my further study of history and killer women

[Epigraph]

The story of women who kill is the story of women.

—Ann Jones, Women Who Kill[1]

Preface

Aileen “Lee” Carol Wuornos, forty-six, died of a lethal injection at Florida State Prison on October 9, 2002. She was the fifty-second person executed since Florida’s reinstatement of the death penalty and the third female execution in the state’s history.[2][3]

Eight hundred and five prisoners have been put to death in the United States since 1976, more than half since 1997? In response to the increase in state killings, the American public has grown less interested in death penalty cases. As a result, news coverage of executions has become inconspicuous. Wuornos’s execution, however, offered the media the opportunity to recount her final hours for an eager audience. The public was informed that she declined her last meal and spent the night reading the Bible, listening to the radio, and meeting with documentary filmmaker Nick Broomfield and with her lifelong friend Dawn Botkins.[4] Botkins told correspondents, “She was looking forward to being home with God and getting off this Earth. She prayed that the guys she killed are saved.... She was more than willing to go. It was what she wanted.”[5]

Florida Governor Jeb Bush signed her death warrant on October 2, 2002, after psychiatrists found Wuornos competent for execution. Her death was timely—a month before Bush’s gubernatorial re-election bid—and controversial as well: four months prior, the Supreme Court ruled that only juries should decide whether to sentence inmates to death.[6][7] In Florida, judges make the decision after a recommendation from the trial jury. However, the Supreme Court’s ruling did not prevent Wuornos’s execution because she confessed more than ten years before, volunteered for execution, and fired her appeal lawyers.

Her cryptic final statement was, “I’d just like to say I’m sailing with the Rock and I’ll be back like Independence Day with Jesus, June 6, like the movie, big mother ship and all. I’ll be back.”[8] After an injection of potassium chloride, Wuornos took sporadic shallow breaths, and her skin slowly turned ashen. She was pronounced dead at 9:47 a.m.

Terri Griffith, a daughter of one of the victims, told reporters, “She got an easy death. A little too easy.... I think she should have suffered a little bit more. Use the electric chair. Let her legs kick and smoke come out of her ears.”[9]

Introduction

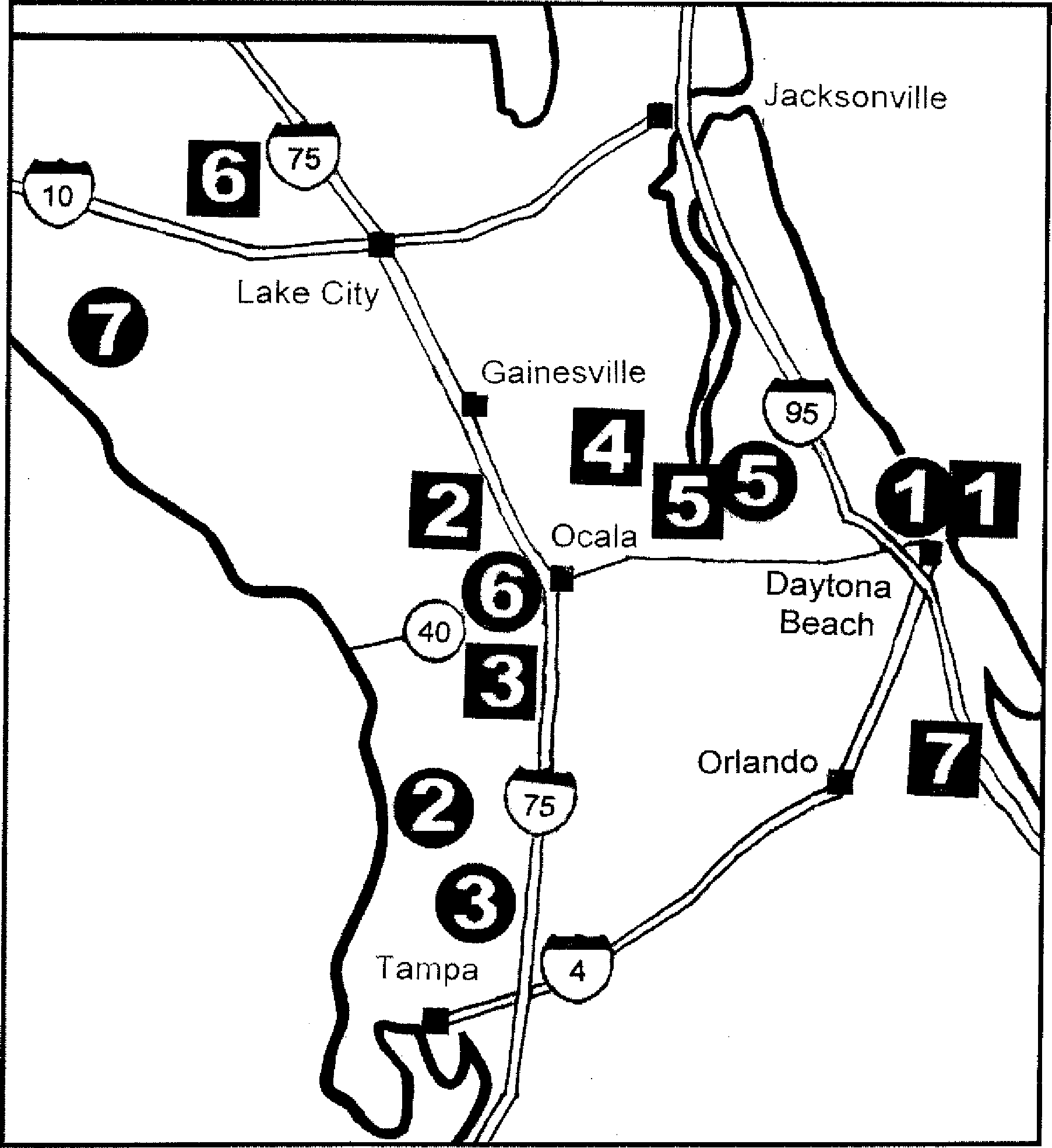

On July 4, 1990, a car careened off State Road 315 near Orange Springs, Florida, and smashed into a fence. Rhonda Bailey, who witnessed the accident from her front porch with her husband and cousin, said that two women exited the vehicle: one, a redhead, the other, a blonde whose arm was bleeding from the broken windshield. The blonde ripped the license plate from the front bumper and tossed it into the nearby woods. Upon noticing Bailey watching her, the blonde woman warned her not to call the police. The two women then drove the car further down the road, abandoning it with a flat tire shortly afterwards. Later that day, Marion County sheriffs deputies discovered that the car belonged to Peter Siems, a sixty-five-year-old retired merchant seaman, who had not been seen since June 22. Siems left his home in Jupiter, Florida, to visit relatives in Arkansas and was reported missing when he did not reach his destination.

Witnesses to the accident described the women to a sketch artist, adding that the blonde might have a heart tattoo on one of her biceps.[10]

Detective John Wisnieski of the Jupiter Police Department wrote a report on the suspects’ appearances and distributed it to local newspapers and television stations.[11]

Two [white females] who appeared to be lesbians were seen exiting the vehicle and leaving southbound on foot. Suspect #1 [white female] 25-30 [years of age] 5’8’7130 [pounds] [blonde hair] [unknown eye color] wearing blue jeans with some type of chain hanging from front belt loop, [white] t-shirt with sleeves rolled up to shoulder. Subject #2 [white female] 20’s 5’4”-5’6’7very overweight and masculine looking w/ [dark red] hair, wearing gray shirt and red shorts....

This description raises several questions. How exactly did these women “appear to be lesbians”? The first suspect may have been perceived as a butch lesbian because she seemed to be wearing a chain wallet, typically worn by working-class men. The second suspect was “very overweight” and “masculine looking.” The latter description is vague: did her physicality (short hair, a cap, and excess weight) imply maleness to her viewers? Regardless, Wisnieski’s descriptors of the second woman indicate that she did not look like a conventional woman and suggest that these women were suspicious not only for driving a missing man’s vehicle, but also for seemingly subverting the feminine ideal.

The perpetrators were later revealed to be Aileen Wuornos and her partner Tyria Moore. In 1991, Wuornos confessed to killing seven men she met while working as a prostitute along Florida’s highways. Subsequently, the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI), followed by the police, the prosecution, and the media, dubbed her the first female serial killer in American history. The label was patently false—women have committed serial homicide in the past, in the United States and elsewhere—yet it was promoted with little question as to its veracity.

The Wisnieski report is just one example of the media’s contribution to Wuornos’s master narrative as America’s first female serial killer. Public narratives form within discourse and are assembled from oral and printed material, radio, television, film, and music. By reporting, the media makes a complicated series of events comprehensible, and its authors and audiences subsequently both create and interpret the narrative’s meaning.[12][13] In other words, the discourse about Wuornos formed a narrative, which told the story, and a metanarrative, which explained the story, simultaneously, What emerged from this narrative was the understanding that Wuornos’s representational labels (white trash, lesbian, prostitute) were overemphasized to detract from the social circumstances that produced a serial killer like her. In examining the narrative, the “truth” of the events leading up to Wuornos’s murders is less important as the discourse of these events; Wuornos the subject becomes more central to the narrative than Wuornos the person. Her representation may be examined to discover her larger cultural meaning during her particular time and place in history.

Raised in a media saturated culture, Wuornos was keenly aware of her representation. In a 1991 Orlando Sentinel article, she asserted, “The media has discredited me so much, making me look like a creep. I’m not a man-hater..,. I am a decent person.”[14] Similarly, while waiving her right to be present for sentencing in her later trials, Wuornos addressed her speech:

to the public, to all the people of the world, and to the news personnel...that have stated defamations and mendacious lies...to vile my character, make me look like a monster and deranged or something like a Jeffrey Dahmer, which I’m not.[15]

To a woman interested in producing a movie about her life, Wuornos simply pleaded, “Please don’t make me a monster.”[16][17] With these statements, Wuornos attempted to defend and humanize herself by employing the media, the same means that had disparaged her.

The narratives about Wuornos revealed the instability of social identity and the anxiety it causes, as illustrated in the discourse explaining how she was both a prostitute and a lesbian. Prostitutes service the intimate needs of their customers, and lesbians do not have sex with men, yet Wuornos engaged in romantic, emotional, and sexual relationships with both sexes. While she lived with Tyria Moore, to whom she referred as her wife, she serviced male customers as a prostitute. Her sexuality could not be clearly denoted and became a source of tension in her narrative.

At the same time, Wuornos’s class identity affected her representation. She was marked as “white trash,” a term that marginalizes poor whites whose behaviors, appearances, or lifestyles do not conform to dominant white culture. Her white trash status was viewed as a motivation behind her crimes, as the media cited her mental state and sexuality as evidence of guilt, as well as alleging that her propensity for violence was inherited.

Another way Wuornos threatened social identity was in her choice of victims: white, heterosexual, working- and middle-class men. As a supposedly white trash, lesbian prostitute, she would be the more likely victim; the men’s profiles were a closer fit to those of serial killers than her’s. In the discourse surrounding her crimes, the media tried to explain how this reversal of roles could have happened. For example, narratives about Wuornos stated that she was not a respectable woman because she was white trash. Similarly, she was not a moral woman because she was a prostitute. As a lesbian, she was not even a real woman. The combined descriptors of white trash, prostitute, and lesbian compounded the threat posed by Wuornos. Through her representation, Wuornos was essentially convicted twice: once for the crimes she committed and again for the threat she posed to the dominant culture.

Making Monsters

If someone had wanted to learn more about serial homicide as Wuornos’s execution loomed, they may have discovered these texts in the criminology section of their local library, among other books with equally salient titles:

The Killers Among Us: An Examination of Serial Murder and its Investigation^ Overkill: Mass Murder and Serial Killing Exposed[18][19]

Serial Killers: The Growing Menace[20]

Serial Murder: An Elusive Phenomenon[21]

Centered on the exploits of individuals such as Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, Henry Lee Lucas, and Richard Ramirez, these books horrified and disgusted their readers, at the same time striking a chord within humanity’s fascination with its own potential for darkness. Their titles alone framed multiple murder as a “growing” and “elusive” trend, one that must be controlled before it further damages the social order.

The books reflected the moral panic about serial killers that occurred as Wuornos met the public eye. A moral panic is the process by which the media and certain political, cultural, and bureaucratic groups mobilize public opinion to turn a minor social phenomenon into a major issue that furthers the groups’ agendas.[22] Historian Philip Jenkins, in Using Murder: The Social Construction of Serial Homicide, contends that the Justice Department, by virtue of its power and access to the media, created a moral panic about serial murder in the 1980s and 1990s. Most notably, the FBI, a division of the department, announced in the early 1980s that serial killers might be responsible for up to five thousand murders a year in the United States, which would account for a quarter of all annual homicides.[23] However, it was later shown that this extraordinarily high estimate was based upon a willful misreading of the statistics.[24] Robert Ressler, a retired behaviorist and criminologist with the FBI, even admitted to intentional misrepresentation in his career memoir. “In feeding the frenzy,” wrote Ressler, “we were just using an old tactic in Washington, playing up the problem as a way of getting Congress and the higher-ups in the executive branch to pay attention to it.”[25] Jenkins notes that the department created a serial killer epidemic to re-establish its diminished credibility, gain national jurisdiction over crimes, and garner more federal assistance in tracking, arresting, and convicting serialists.[26]

This is a partial explanation, because media campaigns succeed in creating panic only if the public accepts its threatening claims. Jenkins indicates two periods, 1983- 1985 and 1991-1992, when the serial homicide moral panic peaked with the help of diverse ideological causes.[27] To conservatives, the serial killer represented cultural decadence and collapsing morality. At the other end of the spectrum, advocacy groups for women, minorities, homosexuals, and children promoted their own agendas by citing homicides in which members of their respective groups were victims.

Regardless of political orientation, each faction referred to serial killers as “monsters.” By definition, a monster is an imaginary creature that inspires horror or disgust. The word signifies abnormality, deviance, and excessiveness, and it originates from the Latin monstrare meaning “to point to” and monre meaning “to warn.” In the context of a moral panic, monsters serve as cultural warnings and point to societal problems. Scholar Edward J. Ingebretsen’s At Stake: Monsters and the Rhetoric of Fear in Public Culture maps a formula for creating and destroying society’s monsters: the monster is identified; the monster is analyzed; and the monster is exorcised.[28][29] In this process, monsters show society by inversion what normal is, or should be. Jenkins agrees, arguing that serial killers “provide a means for society to project its worst nightmares and fantasies, images that in other eras or other regions might well be fastened onto supernatural or imaginary folk-devils.”[30] Society casts its anxieties about class, gender, race, and sexual orientation onto Wuornos’s representation. The monster narrative was constructed to allow society to distance itself from the supposedly unnatural Wuornos and from the historical and cultural context of her crimes.

Relevant Events of 1991 -1992

Wuornos’s arrest coincided with what Jenkins indicates as the second period of the serial killer moral panic, 1991-1992. During these years, interest in Wuornos’s case was maintained by trial coverage on the cable television network Court TV and by features on the news (Dateline NBC), tabloid programs (A Current Affair, Inside Edition), and talk shows (The Montel Williams Show').[31] CBS broadcast the made-for-TV movie Overkill: the Aileen Wuornos Story in November 1992, and Nick Broomfield’s independent documentary Aileen Wuornos: the Selling of a Serial Killer was released later that same year. In addition, several other events exacerbated the panic and made Wuornos’s case particularly attractive to the media.

The FBI reported that 1991 marked an alarming increase in American murder rates.[32] As the homicide rate doubled from the mid-1960s to the late 1970s, it peaked in 1980 at 10.2 victims per 100,000 citizens, or 23,040 murders, and subsequently decreased. It rose to its zenith in 1991 of 10.5 per 100,000, or 24,700 murders. The rate held until 1994, when it declined to 5.5 per 100,000, or 15,517 murders, by 2000. Additionally, statistics indicated a trend of increasing violence perpetrated by women and an overall narrowing of the gap between female and male violence.[33]

Furthermore, 1991 was marked by grisly crimes that received considerable press. Danny Rolling, who mutilated five college students at the University of Florida at Gainesville, was still at large.[34][35] On July 23, police discovered body parts in the apartment of Milwaukee resident Jeffrey Dahmer, who later confessed to murdering seventeen men and boys. Claims of necrophilia and cannibalism further sensationalized the story. Months later, on October 16, George Hennard killed twenty-two people and wounded twenty-three in a Texas cafeteria during the worst mass murder in American history.[36]

Motivated by these events, the Senate passed Bill 266, an anti-crime omnibus that threatened state autonomy in criminal prosecutions and sentencing. It included limits on federal court reviews of prisoner appeals, the addition of nearly fifty felonies punished by the death penalty, and broader standards on the admissibility of evidence seized by the police.

These measures also reinforced the power of the police, who were under scrutiny at the time. In 1992, four Los Angeles policemen were acquitted for charges connected to the Rodney King beating, a verdict that inspired widespread rioting. That same year, law-enforcement organizations threatened to boycott Time Warner after one of its record labels released rapper Ice T’s song “Cop Killer,” whose lyrics blatantly advocated violence towards the police.

Similarly, issues of gender and sexual orientation pervaded the public discourse, such as the Tailhook scandal, the Anita Hill hearings, battles for gay rights, and attacks against abortion facilities.[37] The success of the 1991 film Thelma and Louise, the story of two women’s retaliation against abusive men, may have inadvertently fueled Wuornos’s publicity as well; one Vanity Fair article referred to Wuornos’s case as “a dark version of Thelma and Louise.”[38]

America’s First Female Serial Killer?

In the discourse written before or during her first trial, Wuornos is promoted as the first female serial killer in American history. Although the label sold many media accounts of Wuornos’s life and crimes to a titillated audience, it does not withstand scrutiny.

According to the definition developed by the FBI, a serial killer is a person who murders in “three or more separate events in three or more separate locations with an emotional cooling-off period between homicides.”[39] Wuornos fits this description, but an overview of criminology reveals that she is only one of many homicidal women. Depending on the criteria used, ten to seventeen percent of serial killers are female.[40] One encyclopedia profiles more than eighty female serial killers who acted alone or with female partners, several who killed ten to twenty victims[41] Prevailing theories during the moral panic profiled serial killers as white men in their thirties or forties who kill young women, often prostitutes, or other low-status individuals whose deaths attract little notice from the police.[42] Since this conceptual frame of killer and victim is repeated by the media, any serialist who differs from this construction is not considered a real serial killer, but an aberration like Wuornos.

When Wuornos was characterized falsely as the first female serial killer, the ordinal adjective implied that more would follow. Sergeant Robert Kelley of the Volusia County Sheriff’s Office, who was involved in Wuornos’s investigation, remarked, “Now women are just as capable of being predators,” implying that contemporary women are becoming empowered to kill[43] Similarly, a Psychology Today article about violent women, written shortly after Wuornos confessed, asked its readers, “Women are becoming more stereotypically male in their reasons for murdering.... Have they taken ‘women’s liberation’ one step too far—or are they just showing their natural killer instinct?”[44] By posing this query, the article assumes that a perceived increase in homicidal women is a result of a movement toward gender equality. It also implies that murder is a gendered act and that “liberated” women will act violently like men or their natural inclination to kill will surface. Both arguments are spurious, but the article’s question indicates that some criminal profilers believe men and women kill differently.

Criminologists of the serial killer moral panic, as well as the media, believed that women commit serial murder as black widows who kill their husbands, lovers, or family members in the home or angels of death who kill those in their care, such as patients in a hospital or nursing home. Women are believed to murder those whom they know by poison or suffocation. Men, on the other hand, are said to stalk and slaughter strangers, usually in a larger geographical radius than women, and more violently, by gun or knife.

By that logic, Wuornos’s crimes—fatally shooting strangers along Florida’s highways— were viewed as a masculine way of serial killing.

Even the language used to describe male and female serial killers is gendered. “Black widows” and “angels of death” are feminized and sexualized labels. The nicknames of male serial killers, on the other hand, are tremendously frightening, focusing on the violence itself. A few examples from the 1970s and 1980s include the Hillside Stranglers Kenneth Bianchi and Angelo Buono, the Sunset Strip Slayer Douglas Clark, and the Yorkshire Ripper Peter Sutcliffe.[45] In contrast, Wuornos was called the Damsel of Death and the Highway Hooker, which, in keeping with the other female titles, focus on her gender and sexuality.

True Crime Texts

As the moral panic escalated, the concept of the multiple murderer was adopted into popular culture. For example, in 1992, a line of serial killer trading cards sparked concern about their supposed appeal to children.[46] True crime literature and film saturated the market, such as Bret Easton Ellis’s bestseller American Psycho (1991) and Jonathan Demme’s award-winning film adaptation of Thomas Harris’s Silence of the Lambs (1992)[47] Simultaneously, homicide studies from the fields of criminology, sociology, and history proliferated. Often, as serial murder cases were reported in the news, the lines between fact and fiction blurred.

This obfuscation can be found in true crime books, which combine elements of journalism and detective fiction. Wuornos’s first trial occurred as the true crime genre became more popular than ever before.[48] In a four-year period beginning in 1990, over forty books on case studies and general accounts of serial murder appeared, as did at least twenty collections of briefer studies.[49] Three true crime books about Wuornos were published in 1992 alone: On a Killing Day, Dead Ends, and Damsel of Death.[50] The latter two titles were recently republished, with information about Wuornos’s execution, to capitalize on the 2004 Wuornos biopic Monster.

On a Killing Day, written by Dolores Kennedy with the assistance of Robert

Nolin, a reporter for the Daytona Beach News-Journal, focuses on Arlene Pralle, a woman who legally adopted Wuornos after her arrest?[51] Pralle was offered a share in the book’s profits in exchange for exclusive letters, pictures, and information about Wuornos.[52] Not surprisingly, the book portrays Pralle sympathetically, as someone who cares deeply for Wuornos.

Reuters reporter Michael Reynolds takes a different approach in Dead Ends by examining the forensic evidence and the police investigation. Reynolds even credits himself for breaking the case by having written an article theorizing a connection between the murders.[53]

A British journalist of several true crime books, Sue Russell weighs in with over 500 pages in Damsel of Death. Her research partner was Jackelyn Giroux, who was involved in the Wuornos movie Overkill', she later starred as Wuornos in Damsel of Death: The Aileen Wuornos Story, a film she wrote, directed, and produced.[54] In her book, Russell concentrates on Wuornos’s early home life, drawing conclusions from Giroux’s extensive interviews with Wuornos’s childhood acquaintances.

True crime books like these attempt to construct an orderly narrative out of a complex reality. For instance, the texts focus on the police investigation and court proceedings—processes, though efficient in print, are convoluted in real life. The books contain numerous portraits of law enforcement officials and lawyers standing before police stations and courthouses, illustrating a desire for the restoration of order upon Wuornos’s conviction.

Although the authors approach Wuornos’s narrative differently, they all take liberties in constructing the events that led to the murders. Kennedy and Nolin insert italicized pieces into Wuornos’s courtroom testimony about her first victim, which undercuts her claim that he attacked her first. Similarly, Reynolds and Russell construct passages in which Wuornos stalks and kills her victims, as in the following selection from Dead Ends'.

“No, motherfucker. You’re not going anywhere at all. Get down on your knees.”

He was still jabbering on, but she no longer cared what he said. It sounded like begging. She wanted that.... “Not much without your clothes, you old fuck. You know that?”

She considered the first shot, aimed, and fired. The white body jerked. She cocked the hammer on the clunky Double Nine with her thumb and fired another right behind the first. He was down on his hands. She stepped closer, centered the five-and-a-half inch barrel on the base of his skull. Cocked and fired. His head jumped. She could hear him make these noises, little grunts and moans. One more. She stood over him, lowered the pistol, sighted on the protruding disks of his spine. Cocked. Steady. And fired. His knees gave way immediately and he slumped to his left. She watched him fold slowly into a fetal curl. He made no more noises. She saw something glisten in the dirt to his right. She reached down and picked up a row of teeth, holding them gingerly between her finger and thumb. She had to laugh.[55]

In this highly dramatized scene, Wuornos is portrayed as a monster who taunts her victim and coldly murders him execution-style. Her last action—laughing at the teeth that she plucked from the dirt—is purely speculative and excessively gruesome.

Aileen Wuornos’s Life and Crimes

The texts also construct a relatively similar account of Wuornos’s life, focusing on her abusive upbringing and her criminal history, as the following section illustrates. Aileen Wuornos was bom on February 29, 1956 in Rochester, Michigan, to teenaged parents Dale Pittman and Diane Wuornos, who separated before her birth. Diane, overwhelmed by raising Aileen and her older brother Keith as a single mother, gave custody of them to her parents, Lauri and Britta Wuornos, in Troy, Michigan, in 1960. Diane lost touch with her children and began a new life in Texas, briefly meeting them again when they were teenagers. Pittman, the birth father Aileen never met, killed himself in prison in 1969 while serving time for child molestation and murder,

Wuornos became sexually active early in her childhood. She engaged in incest with her brother and her grandfather. At twelve, Wuornos was shocked to discover that Lauri and Britta were not her parents, but her grandparents. Around the same time, she began offering sexual favors to the neighborhood boys in exchange for money and drugs. Wuornos became pregnant at fourteen after she was raped by a family friend. She was sent to an unwed mothers’ home in Detroit, where she gave her infant son up for adoption.

Soon afterwards, her grandmother Britta died, and while her death was blamed on liver failure from alcoholism, Wuornos’s mother, Diane, suspected Lauri of Britta’s murder. After her death, Wuornos and her brother were kicked out of their house by their grandfather. Wuornos soon dropped out of school and supported herself by prostitution, first in her home state of Michigan, then in Colorado, and later in Florida. During her first year as a runaway prostitute, she was beaten and raped at least six times by as many men.[56]

Wuornos’s young adulthood was equally chaotic. During her twenties, her grandfather killed himself, and her brother died of throat cancer, leaving her a substantial insurance payment that she quickly spent. She tried to kill herself during this period; her most serious attempt, shooting herself in the abdomen, hospitalized her for two weeks. At twenty-two, she married elderly Lewis Fell, but they were divorced a month later after they accused each other of physical abuse.

Under a string of aliases, Wuornos was arrested numerous times in the 1970s and 1980s for offenses including drunkenly firing a ,22-caliber gun from a car in Colorado, throwing a cue ball at a bartender’s head in Michigan, and attempting armed robbery at a Florida convenience store, for which she served fourteen months in prison. While in Florida, she was arrested for check forgery and auto theft, suspected in the theft of a pistol and ammunition, and accused of demanding money from a friend at gunpoint. Although she worked as a highway prostitute for most of her life, she was never arrested for this crime.

In 1986, Wuornos, age thirty, met twenty-four-year-old Tyria Moore at the Zodiac, a Daytona Beach gay bar. Moore had recently relocated to the area from Ohio after receiving an insurance settlement from an automobile accident. In 1987, police detained the women for questioning, on suspicion that they had assaulted a man with a beer bottle, and in 1988, a landlord accused the pair of vandalizing their apartment.

Moore occasionally worked as a motel maid and allowed Wuornos to support her while they lived in a series of trailers and motel rooms in Daytona Beach.

In a yearlong period, Wuornos killed seven customers with a .22 caliber revolver.[57] The first victim, Richard Mallory, was found on December 13, 1989. The lifeless body of David Spears was discovered on June 1, followed five days later by that of Charles Carskaddon. Peter Siems was last seen in early June. Eugene Burress’s body was located in August, and September marked the discovery of Dick Humphreys’s remains. The corpse of the last victim, Walter Antonio, was unearthed in November.

Initially, the police were slow to link the murders because they occurred in five different counties.[58] The cases had similarities, though: the victims were middle-aged or older, traveled alone, and were killed by multiple shots chiefly to the torso. They were found covered in debris in secluded areas with their cars abandoned elsewhere and wiped to remove prints.[59] Some of the men were found fully or partially nude near condom wrappers, which suggested that they had sex before their deaths. This possibility was not mentioned in news reports until Wuornos’s arrest; the men’s clothes could have been removed to delay identification, and the police wanted to save the victims’ families needless embarrassment.[60]

Although some personal property was missing, a robbery motive was discounted because money was left at the scene. Investigators theorized that the murderer faked car trouble or started conversations with the men at rest stops to create opportunities for the killings.[61] A local criminologist even suggested that a female impersonator might have committed the homicides, because he did not believe that they were characteristic of women.[62]

In November 1990, the similarities in the cases caused the police to release the sketches of the women involved in the accident with Siems’s car. The couple was identified as Wuornos and Moore, and the police began searching for them. Officers checked area pawnshops and discovered that Wuornos, under an alias, pawned items from two of her victims and left the requisite thumbprint on the receipt, which matched a print on a victim’s car.[63] Sensing that she and Wuornos would soon be located, Moore fled to her parents’ house in Ohio at Thanksgiving, briefly returning to Florida to gather her belongings. During the Christmas holidays, Wuornos was tracked by investigators and arrested on January 9, 1991, at the Last Resort, a Daytona Beach bar. The next day, detectives traced Moore to her sister’s home in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and returned her to Florida to assist the investigation.

Moore was not granted immunity, nor did she plea-bargain; she was simply never charged with any crime. She entered into a partnership with investigators to profit from selling Wuornos’s story to as many as fifteen interested film companies.[64] During a series of taped conversations, Moore convinced Wuornos to admit to the crimes. On January 16, Wuornos confessed to killing everyone except Peter Siems, whose body was never located. Wuornos absolved Moore of any knowledge of or assistance in the homicides, and Moore turned state’s evidence against her former lover. They never spoke together again.

In her confession and during her 1992 trial for her first victim, Richard Mallory, Wuornos claimed that she killed the men because they raped, beat, or attempted to harm her. Although her subsequent victims did not have histories of sexual assault, Mallory did: he served ten years in prison for the attempted rape of a Maryland woman. This information was never entered into evidence by either side, because the prosecution revealed it immediately before the trial and the defense was instructed not to pursue it.[65] In a television interview after the trial, prosecutor John Tanner admitted carelessness in investigating Mallory’s past and wondered if the new evidence would overturn the case.[66] Tanner need not worry: the court did not accept Wuornos’s self-defense plea, and she was convicted of first-degree murder and given the death penalty. In the years that followed, she pled guilty to the remaining homicides and received five additional death sentences.

Arlene Pralle, a forty-four-year-old born-again Christian who ran a horse ranch near Ocala, Florida, befriended Wuornos after reading about her in the newspaper. During Wuornos’s trials, Pralle became Wuornos’s advocate, speaking with her daily and claiming her innocence on television and radio talk shows. Concerned that others might question her motive for assisting Wuornos, Pralle stated, “People are going to try to make it into a ‘sexual perversion,’ but it’s not like that at all. It’s a soul binding. We’re like Jonathan and David in the Bible."[67] On November 22, 1991, Pralle and her husband legally adopted Wuornos. As Wuornos’s guardian, Pralle could visit Wuornos more often, as well as profit from selling the rights of Wuornos’s story.[68] Growing suspicious of Pralle’s intentions, Wuornos ceased contact with the woman after a few years. In 2000, Pralle removed herself from the media spotlight by moving to the Bahamas[69]

For the next ten years on Florida’s death row, Wuornos attempted to expedite her execution by issuing damning statements in the courts. For instance, she yelled at a judge, “All I want to do is go back to prison, wait for the chair, and get the hell off this planet that’s full of evil and your corruption in these courtrooms!”[70] She abandoned her self-defense plea, first stating that she murdered the men to rob them, and then claiming that she simply killed them in cold blood. In a letter to a judge requesting that he drop her appeals, Wuornos warned, “I’m one who seriously hates human life and would kill again.” Monstrous statements like this hastened Wuornos’s death.[71]

Wuornos’s Representation as White Trash

Wuornos’s murders have been explained in part by labeling her white trash, a term that marginalizes economically disadvantaged whites who do not conform to the dominant middle class white culture. “Poor white trash” dates back to the early nineteenth century when slaves used it in reference to white servants; the southern white elite quickly appropriated the label.[72] The term’s ideology developed in nineteenthcentury eugenic studies and continued in popular depictions of white trash in the early 1990s when Wuornos received national exposure. Her representation shows how her white trash status was linked to criminality through an inherited propensity for violence, a presumed deranged mental state, and a perverse sexuality.

White Trash Ideology

Several works have attempted to portray the social history of poor, working-class whites.[73] Systematic and fair studies have rarely been conducted on the subject of the indigent white population because historians, like many people, stigmatize the poor and project onto them the qualities that the term “white trash” conveys. “White trash” invokes stereotypes of impoverished whites as simple-minded, shiftless, and inbred, prone to promiscuity, incest, and aggression, as well as a host of other social ills. Although this group seems more prevalent in the South and rural areas, white trash can be found everywhere in America: even in urban, northern, and predominately minority cities like Detroit.[74] Creating a more sympathetic history, though, would not diminish the purpose of labeling white Others. The term serves as a boundary to separate whites who defy white, middle-class norms in America. Just as whiteness is maintained by excluding members of other ethnic and racial groups, white trash denotes the site where whiteness and poverty meet.[75]

The causes of the perceived degeneracy of certain whites were examined in family studies produced between 1877 and 1926 by the U.S. Eugenics Records Office.[76] Claiming to demonstrate scientifically that large numbers of poor whites were genetic defectives, these studies traced the genealogies of incarcerated or institutionalized people to supposed faulty sources.[77] By solely focusing on genealogy, eugenic studies found biological reasons for deviancy, rather than economic or social explanations.[78] The accounts affected social policy and medical practice into the early twentieth century.[79] Conservatives used the findings to call for a minimization of aid for the destitute, while medical and psychiatric centers utilized them to institutionalize and sterilize poor whites.

Eugenics was discredited when the Nazis, adopting the same politics, followed them to their logical conclusion: genocide. In recent years, however, books like Richard Heimstein and Charles Murray’s The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (1994) have promoted Social Darwinism and biological determinism as an explanation for cultural and class differences and imply a need to end the welfare state.[80]

The deployment of the term “white trash” continued to function as a way to tie poverty to genetics, to mitigate poor people’s claims for social justice, and to solidify the middle and upper classes in a sense of cultural and intellectual superiority.

In the 1990s, American pop culture was saturated with images of white trash, albeit without portraying the harsh social, economic, or historical conditions that produce poverty. President Bill Clinton was considered white trash due to his Arkansas upbringing, his mother’s love of Elvis, and his sexual dalliances with “trashy” women. Americans followed white trash scandals involving ice skater Tonya Harding, husbandmutilator Lorena Bobbitt, and soured lovers Joey Buttafuoco and Amy Fisher. Sitcoms such as the highly-rated Roseanne, as well as Married with Children, Grace Under Fire, and Beavis and Butthead, found humor in white trash protagonists, and talk shows like Jerry Springer brought real-life white trash into American homes.[81]

During this time, white trash was reconfigured into an even more violent caricature than before. A New York magazine piece titled “White Hot Trash!”, one of many articles on America’s fascination with white trash, linked it to serial murder: “True trash is unsocialized and violent.... An even more damaged trash response than being [a Hell’s Angel] is serial killings.”[82] Although poor, working-class whites often were portrayed as criminally minded, homicide, especially multiple murder, was now considered white trash behavior.

The nineties also saw a string of feature films that portrayed white trash serial killers: Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1990), Kalifornia (1993), and Natural Born Killers (1994). In these movies, the motivation for the sadistic slaughter, whether explicit or implied, was the murderers’ white trash status. Natural Born Killers, for instance, takes its title from a monologue in which the protagonist explains his reason for killing: “I came from violence; it’s in my blood. My dad had it. His dad had it. It’s fate.... I guess I’m just a natural bom killer.”[83] This film, as well as the others, presupposes that white trash is not merely a cultural situation, but an inherited attribute. Even more distressing is the notion that an inclination to multiple murder is inborn in those labeled white trash.

White Trash Representation

At the time when white trash was coupled with serial murder, Wuornos’s story exploded into the news. Her background interested the media, particularly her biological father, Leo Pittman, whom she never met. Reporters sought information about him, rather than about Wuornos’s biological mother or her maternal grandparents who raised her, because he had a violent criminal record and they did not.

The media emphasized that, like Wuornos, Leo Pittman, and his sisters were abandoned by their natural parents and raised by their grandparents. During his childhood, Pittman was reportedly a chronic truant, a poor student, and a discipline problem as Wuornos had been. After his brief marriage to Wuornos’s mother, Pittman served probation for breaking and entering and three years in prison for car theft. In 1962, he kidnapped, raped, and sodomized a seven-year-old girl. After his arrest, he was considered a suspect in the assault and murder of several girls, although he was never charged with these crimes. Diagnosed as schizophrenic, Pittman hung himself at thirty- three, a few years into his sentence of life imprisonment.

Sue Russell’s Damsel of Death cites Pittman’s tendency to keep guns in his car as “[a]nother foreshadowing of Aileen’s behavior.”[84] The book also asserts that Wuornos’s homicidal nature was inborn:

[Pittman’s] potent contribution to...his daughter was an inherited predisposition towards criminal behavior. Studies have shown that the biological legacy of criminality is even more powerful than the environmental in determining the outcome of the child. Even if that child is removed from the parent soon after birth (or, in Aileen’s case, before it) and raised in a different environment, the odds are that they will be a chip off the old block.[85]

Russell does not cite the reports she references, but she assumes that these undoubtedly controversial studies, if they exist at all, are common knowledge. Although Leo Pittman was a violent criminal, there is no evidence, beyond the author’s imagination, that Wuornos inherited his behavior. Instead, just as the eugenic studies traced their subjects back to their faulty source, the media wanted to discover the genetic cause for Wuornos’s violent behavior.

Wuornos was also deemed mentally defective. Psychologists described her as primitive, childlike, and perceiving the world as “having evil spirits, ghosts, things that are beyond...control.”[86] Her IQ, rated low dull normal, was considered borderline retarded.[87] Although the structure of her brain was apparently without defect, it functioned improperly “like sand in a gas tank,” as one psychologist phrased it.[88] Nick Broomfield, in his 1992 documentary Aileen Wuornos: the Selling of a Serial Killer, claimed that Wuornos’s monstrous brain would be preserved for study after her execution.[89] No evidence exists of this happening, and Broomfield does not disclose the source of such bizarre information.

Wuornos’s white trash status was also cited when she was diagnosed with both borderline and antisocial personality disorders. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a reference guide to all recognized psychiatric problems, defines borderline personality disorder as “a pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects, and marked impulsivity beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts.” Likewise, antisocial personality disorder is defined as “a pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others occurring since age 15 years.”[90] These definitions are vague enough that a great many people qualify as having such personality disorders. Furthermore, disorders are not biologically proven, nor do they have a definite pathology or cause. Instead, a diagnosis J is made when certain ambiguous criteria of unacceptable behavior are met—behavior which is socially and historically defined—making mental illness a social construct.

Wuornos, therefore, was diagnosed with personality disorders because her violent acts were unacceptable. Proponents of the diagnoses of mental illness cited her courtroom outbursts as confirmation of her aggressive tendencies. When Wuornos was found guilty of the first-degree murder of Richard Mallory, her initial shock turned to fury. As jury members left the courtroom, she shouted, “Sonsabitches! I was raped! I hope you get raped! Scumbags of America!”[91] Later, during the trial for the murders of Dick Humphreys, Troy Burress, and David Spears, Wuornos yelled at Assistant State Attorney Ric Ridgeway, “I’ll be in heaven why y’all be rotting in hell.... May your wife and kids get raped.. .right in the ass!”[92] Led out of the out of the room, she continued, “I know I was raped, and you ain’t nothing but a bunch of scum. Putting someone who was raped to death? Fucking motherfucker!” and made an obscene gesture to the judge. These verbal assaults, repeated ad nauseam in print and video, were attributed to her personality disorders and deemed characteristic of her crass, white trash nature.

Accounts of Wuornos’s crimes also position her in locations established as decidedly low-class. For example, in Aileen Wuornos: the Selling of a Serial Killer, director Broomfield visited the Last Resort, the biker bar where Wuornos was arrested. In the discourse surrounding Wuornos’s crimes, she was often described as a regular patron, one who hustled pool and customers and listened to Randy Travis’s “Diggin’ Up Bones” on the jukebox. When interviewed by Broomfield, Cannonball the bartender explained that Wuornos was an infrequent customer. Broomfield returned the next day to film the Human Bomb, an acquaintance of Wuornos who lights explosives underneath himself for entertainment. Broomfield panned the crowd of menacing bikers, recorded the explosion, yet failed to interview the Human Bomb. The extensive footage at the Last Resort established Wuornos in a white trash context.

Broomfield also narrated the details of the case over images of desolate highways and dilapidated trailers, the visual equivalent of the seediness he described. He filmed the bleak Fairview Motel in Daytona Beach, where Wuornos lived with Tyria Moore before her arrest, focusing on the late model trucks in the dirt parking lot. This shot established Wuornos’s transient lifestyle, as well as her deviation from middle-class domesticity.

Wuornos’s sexuality was marked white trash because it deviated from respectable gender and sex norms. Wuornos called Moore her wife, which suggests that they were a butch/femme couple. Butch/femme, as feminist commentators like Dorothy Allison have noted, is often associated with working-class lesbians and is sometimes stigmatized by middle-class lesbian feminists as a retrograde form of sexuality.[93] Additionally, Wuornos was viewed as a promiscuous woman, supporting herself through prostitution for most of her life. She worked on the street, rather than ostensibly higher-class establishments like a brothel or an escort agency. Her customers were working- and middle-class men who had better jobs and higher status than she did and the material comfort and stability that she lacked.

When the dominant culture labels a person like Wuornos as white trash, it deliberately marks the boundary between that person and respectable, white, middle-class society, thereby lessening the threat posed to traditional mores. More important, the preoccupation with Wuornos’s allegedly inherited violence and mental illness is practically an endorsement of the outmoded concept of eugenics. If Wuornos was genetically predisposed to serial killing because she was white trash, the responsibility of the crimes rested solely on her. Thus, Wuornos remained an aberration, rather than a symptom of greater social ills that could produce others like her. In this view, the question of whether Wuornos may have acted in self-defense lost its relevance since she would have killed anyway—murder was in her genes. Just as the use of the term “white trash” has mitigated the claims of poor people for sympathy throughout American history, labeling Wuornos as white trash removed all culpability other than her own, rendering her irrefutably guilty in the eyes of many.

Wuornos’s Representation as a Prostitute

In the closing arguments of Wuornos’s first trial, prosecutor John Tanner declared, “[Wuornos] is not a victim because she is a prostitute. She has chosen to be a prostitute.”[94] This statement characterized the attitude of the media and the public at large towards Wuornos’s occupation, when, in her narrative, she was depicted as a predatory prostitute who stalked the highways. In the discourse about Wuornos, little acknowledgement was granted to her limited employment opportunities, the law that favored the rights of customers over prostitutes, or the danger she faced on a daily basis. Instead, her motivation for murder was blamed on her livelihood: some believed that she killed because her career was failing, others thought she found perverse pleasure in slaying her sex partners. Either way, the narrative stressed the “unnaturalness” of the more likely victim, the prostitute, killing her customers. In doing so, according to the discourse, Wuornos revealed her monstrous disposition.

Wuornos’s Work Conditions

Throughout her life, Wuornos worked intermittingly as a waitress, cashier, maid, and pool hustler. At one point, she planned to start a carpet cleaning business with an exlover, but the woman stole the equipment.[95] Wuornos explored alternatives to prostitution, but her limited education and funds prevented her from pursuing them, as she explained in her confession:

I tried to be a police officer but they wanted like three thousand dollars, and I didn’t have my GED. I tried to be a corrections officer but didn’t have a car, couldn’t get into the military because I couldn’t pass the tests...the only thing I could do was be a prostitute.[96]

Prostitution was not so much of a “choice” for Wuornos as Tanner claims, but one in a narrow range of occupations available to her.

Wuornos’s work was cyclic: she labored three to four days in a row, returned home for a day or two, and then went out again.[97] By her account, she met up to fifty men a day and had sex with three to six of them.[98] When they completed the act, or if the men were not interested in her services, she was dropped off at the nearest exit and began again. Wuornos said, “I brought home about $300 every two weeks, but it wears you out, constantly talking to all those men, staying up.”[99] She charged $30 for fellatio, $35 for vaginal sex, $40 for both oral and vaginal sex, and $100 for an hour of sex.[100] Most of her customers wanted oral sex, which took the shortest amount of time to complete, but it also meant that she would have to service more customers to make as much money as her other acts.[101]

Wuornos stated in her courtroom testimony that she had sex with hundreds— perhaps thousands—of men and killed only seven of them because they gave her trouble.[102] Problematic customers could be physically or verbally abusive, refuse to compensate her, pay less than they agreed on, or demand services that she did not want to perform. In her confession, she recalled, “I thought to myself, why are you givin’ me such hell [because] I’m just tryin’ to make my money.”[103] In Fatal Women, a book about female aggression and sexuality, cultural theorist Lynda Hart points out that Wuornos did not believe that she was a serial killer, because it was common for customers to become violent and when they did, she had to defend herself.[104] During her first trial, Wuornos affirmed this view:

I’m supposed to die because I’m a prostitute? No, I don’t think so. I was out prostituting. And I was dealing with hundreds and hundreds of guys. You got a jerk that’s going to come along and try to rape me? I’m going to fight. I believe that everybody has a right to self-defend themselves.[105]

Evelina Giobbe, founder of a support group for ex-prostitutes, Women Hurt in Systems of Prostitution Engaged in Revolt (WHISPER), agrees, “Aileen’s fears [were] not unfounded. Close to 2,000 men a year used her in prostitution. So to say three to six a day, that seven of them may have sexually assaulted her fits with the stats....”[106] Given the sheer number of customers that Wuornos serviced in a year’s time, it is conceivable that seven of these men would use violence against her and that she felt obligated to defend herself.

Numerous studies have documented the frequent incidence of robbery, assault, rape, and murder against sex workers, indicating that street and highway prostitutes face the highest risk of violence.[107][108] Prostitutes usually work in their own neighborhoods, while customers who live elsewhere drive into these areas with greater ease and 108 discretion, and sex acts usually occur in the customer’s car that he controls.

Additionally, prostitutes without pimps, like Wuornos, cannot depend on the protection they could offer them.[109] Wuornos also increased her risk of abuse when she was forced to solicit more strangers when her trusted regulars left for Operation Desert Storm in the 1990s.[110]

Philippa Levine, a history professor at Florida State University, noted that rape against prostitutes was common, yet rarely prosecuted in a 1988 prostitution report for the Gender Bias Study Commission of Florida’s Supreme Court.[111][112] [113] Additionally, a 1991 study by Portland, Oregon’s Council for Prostitution Alternatives documented that 78% of fifty-five prostitutes reported being raped an average of thirty-three times annually by their customers; although twelve sexual assault charges were brought against the rapists, none were convicted. In Wuornos’s case, she claimed that she was raped four times during the year before her murders, in addition to the seven assaults attempted by her victims. Her accusations struck many people as implausible, because prostitutes are often viewed as willing to have sex with anyone and, therefore, cannot be raped. During a television interview, Wuornos said:

I don’t understand how nobody can understand how a prostitute can be raped. Because when a man rapes a woman, he assaults your whole body. He puts his [censored by network] down your throat, cramming it down your throat. He tears your hair out of your head. He beats your face in. He rips your [censored by network] wide open.[114]

In this statement, Wuornos counteracted the assumption that prostitutes deserve abuse and should passively presume the risk of rape in their occupation. Since Wuornos defended herself, she was unrepentant. During a Dateline NBC interview, for example, she said:

Here’s a message for the families: You owe me. Your husband raped me violently, [Richard] Mallory and [Charles] Carskaddon. And the other five tried, and I went through a heck of a fight to win. You owe me, not me owe you.”[115]

In another interview, when asked to apologize to the “innocent families,” Wuornos stated, “Those families aren’t innocent [because] those men aren’t innocent. I’m not giving in. Those men are not innocent.”[116] In these statements, Wuornos placed the blame for her actions not only on her victims and their families, but also on society, for allowing men like her customers to believe that they are entitled to have full access to women’s bodies.

In addition to dangerous work conditions, Wuornos had to contend with the law, specifically Florida Statute 796 (1988).[117] A reading of the statute illuminates the greater risks of arrest and harsher sentences prostitutes could receive compared to their customers.[118] The first six sections of the statute concern those who benefit from the prostitutes’ work, namely madams, escort business owners, and pimps. Of these statutes, the strongest penalty, a second-degree felony, is reserved for one who coerces another under the age of sixteen into prostitution. Coercion of someone older than sixteen, benefiting from the earnings of prostitution, or running a house of prostitution are each considered third-degree felonies. Philippa Levine states that the overall statute was gender-neutral, but its interpretation and implementation were biased.[119] For example, coercion and deriving support from the proceeds of prostitution are hard to prove and rely on the prostitute’s testimony. Usually, if the lesser charge of aiding and abetting in prostitution is pursued at all, it results in a misdemeanor conviction rather than a felony.[120][121] Additionally, section 796.08, “screening for sexually transmissible diseases; providing penalties,” seems to treat customers and prostitutes equally, but its implementation does not. Since they are convicted more often than customers are, prostitutes are tested more frequently as well, increasing the likelihood of being convicted of knowingly engaging in prostitution with a sexually transmitted disease.

Customers usually receive less jail time than prostitutes and can leave jail without being tested, due to a screening backlog. Although Wuornos was never arrested for prostitution, the statute illustrates how she labored in an environment that gave preference to the rights and privacy of customers over prostitutes.

Prostitute Representation

Wuornos’s monstrous narrative attributed her motivation to murder to her occupation. Some accounts have labeled her a sexual serial killer because she engaged in prostitution with her victims before the murders.[122] In Wuornos’s case, she and her victims either consensually engaged in sex or the men raped or attempted to rape her; Wuornos did not sexually assault her victims.

Similarly, Marion County Sheriff’s Sergeant Munster, who coordinated the investigations of several victims, blamed what he viewed as Wuornos’s faltering prostitution career for her desire to kill. Paraphrasing Munster’s sentiments, author Michael Reynolds writes:

Her prostitution career had clearly been on the skids. She’d made no effort at grooming when she went out, no makeup, no sexy dresses. She didn’t even own a dress. This dishwater blond with a beer gut had hit the highways in a pair of cutoffjeans, a Marine camo t-shirt, a ball cap and a pair of sneakers, toting a plastic bag loaded with a ten-inch nine-shot revolver.[123]

Wuornos, in reality, did not attract any less business than she normally did when she began killing her customers. Wuornos chose to dress in an inconspicuous style, rather than wear “sexy dresses,” since such costumes would be overly obvious to police and thus inappropriate for working on a busy highway. She also did not murder for money, although at one point she claimed otherwise in the hope that it would hasten her execution.

Criminology sources echo the robbery motive. Forensic psychiatrist John MacDonald’s book Rape: Controversial Issues lists Wuornos under the “Homicide and Rape: A Monstrous Crime” section, stating that “[I] like many male serial murderers, Aileen Wuornos used a con approach to persuade victims to go to an isolated place, then killed and robbed them.”[124] Similarly, criminologists Jack Levin and James Alan Fox place Wuornos under the category of “Women Killing for Profit and Protection,” claiming that her motive was greed.[125]

As the narrative attributed various motivations to Wuornos, the metanarrative demonstrated how a prostitute killing customers reverses the “natural” order of power in society. In a 1991 Dateline NBC interview with Wuornos, anchor Jane Pauley introduced the segment with these significant words: “This is a story of unnatural violence. The roles are reversed. Most serial killers kill prostitutes.”[126] These statements imply that killing prostitutes is natural. Hart writes, “whereas male serial killers are ‘naturally unnatural,’ as a woman, Wuornos has committed unnatural unnatural acts.”[127] In other words, male killers are considered more natural than female killers because the tendency towards violence is perceived to be inherently masculine. Wuornos becomes monstrous for two reasons: not only is she a woman who kills, but she is a prostitute who kills customers.

In her representation, Wuornos’s occupation as a sex worker was believed to be a motivation for her murders. Instead of viewing her work as a situation that put her at considerable risk and disadvantage to her customers—such as convicted rapist Richard Mallory—she was depicted as being a sadistic monster who slaughtered for money or sex. By portraying her this way, the narrative removed society’s culpability in producing a culture that ignores and implicitly allows prostitutes to be robbed, raped, and killed on a regular basis, yet condemns them for defending themselves.

Wuornos’s Representation as a Lesbian

“In our part of the state/the ‘lesbian’ label is just as damaging as ‘serial killer,’” noted Tricia Jenkins, Wuornos’s defense lawyer during her first trial.[128] Jenkins had a point: the most damaging aspect of Wuornos’s representation was the discourse about her homosexuality. Discussing Wuornos in a 1992 Advocate article, journalist Donald Suggs writes, “As the media coverage attests, the answer to this question [of whether Wuornos is a serial killer] has little to do with how many men the Florida prostitute may have killed and everything to do with how the crime is classified by gender, and in this case, sexual orientation.”[129] Writing for a gay audience, Suggs got to the heart of Wuornos’s media representation: in some minds, her sexuality merged with her criminality.[130][131] Since Wuornos’s narrative stated that she was not a “real” woman—that is feminine and heterosexual—her lesbianism not only demonized her, but also allowed her to commit serial murder.

Lesbian Gender

The 1990s saw a resurgence of issues surrounding lesbian butch/femme identity in both the straight and gay worlds. In “Butch-Femme and the Politics of Identity,” 1 0 t historian Tracy Morgan outlines the butch/femme lesbian sex war of the 1990s. The butch, Morgan states, can be traced back to the advent of sexology when mannish women were labeled “inverts.” The femme lesbian, on the other hand, was defined by her relationship with a butch; the femme’s ability to pass as heterosexual denied her an identity of her own. Morgan, as well as Joan Nestle, a founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives and editor of The Persistent Desire: A Butch/Femme Reader (1992), comment on the resurgence of the butch-femme aesthetic in the 1990s, marked by work such as Stone Butch Blues, a novel about butch identity, and Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community about Buffalo’s butch/femme bar life.[132] Lesbian identity was discussed in the mainstream as well, when popular shows like Donahue focused on butch and femme lesbians.[133]

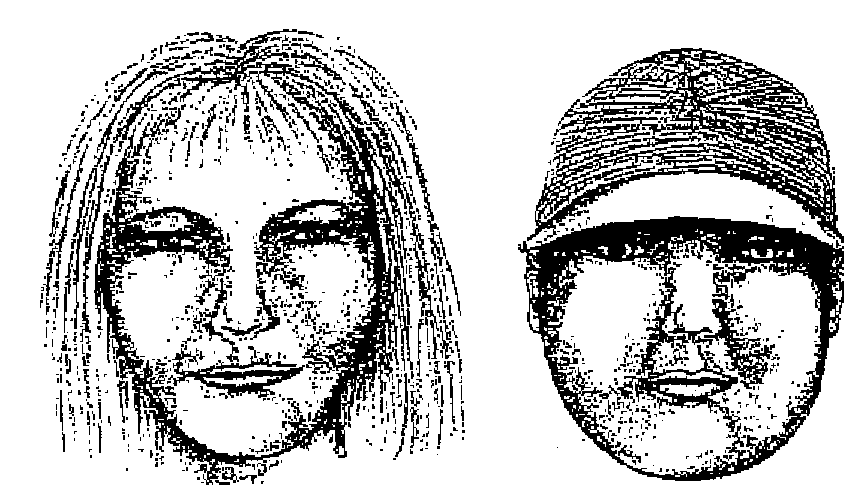

Within this context, constant tension arose from Wuornos’s dichotomous portrayal as a femme prostitute who lured men into illicit sexual relations and a butch serial killer who murdered them in cold blood.[134] These roles were never transposed— Wuornos was not depicted as a butch prostitute or a femme killer—because conventionality reasons that prostitutes are not masculine and killers are not feminine. Wuornos’s transition between butch and femme was evident when she was compared to girlfriend Tyria Moore. In Detective Wisnieski’s description of the suspects involved in the accident with Siems’s car, Moore was described as “masculine looking” due to her stockiness, the cap obscuring her short hair, and her heavy jaw in her sketch. Wuornos’s drawing was more feminine, featuring her long, blonde hair and high cheekbones that were more pronounced in her sketch than in real life. When the pictures are compared, Moore was marked, textually and visually, as the more masculine of the pair.

The dyad reversed after Wuornos confessed. Upon taking full responsibility for the murders, Wuornos found that public attention-—and masculinity—centered on her. Moore was described at this point as having had knowledge of, but not participating in, the killings, and her stable, supportive family and middle-class background were emphasized in contrast to Wuornos's tragic history. Similarly, emphasis was placed on Wuornos’s reference to Moore as her wife and that Wuornos supported her while they were together.

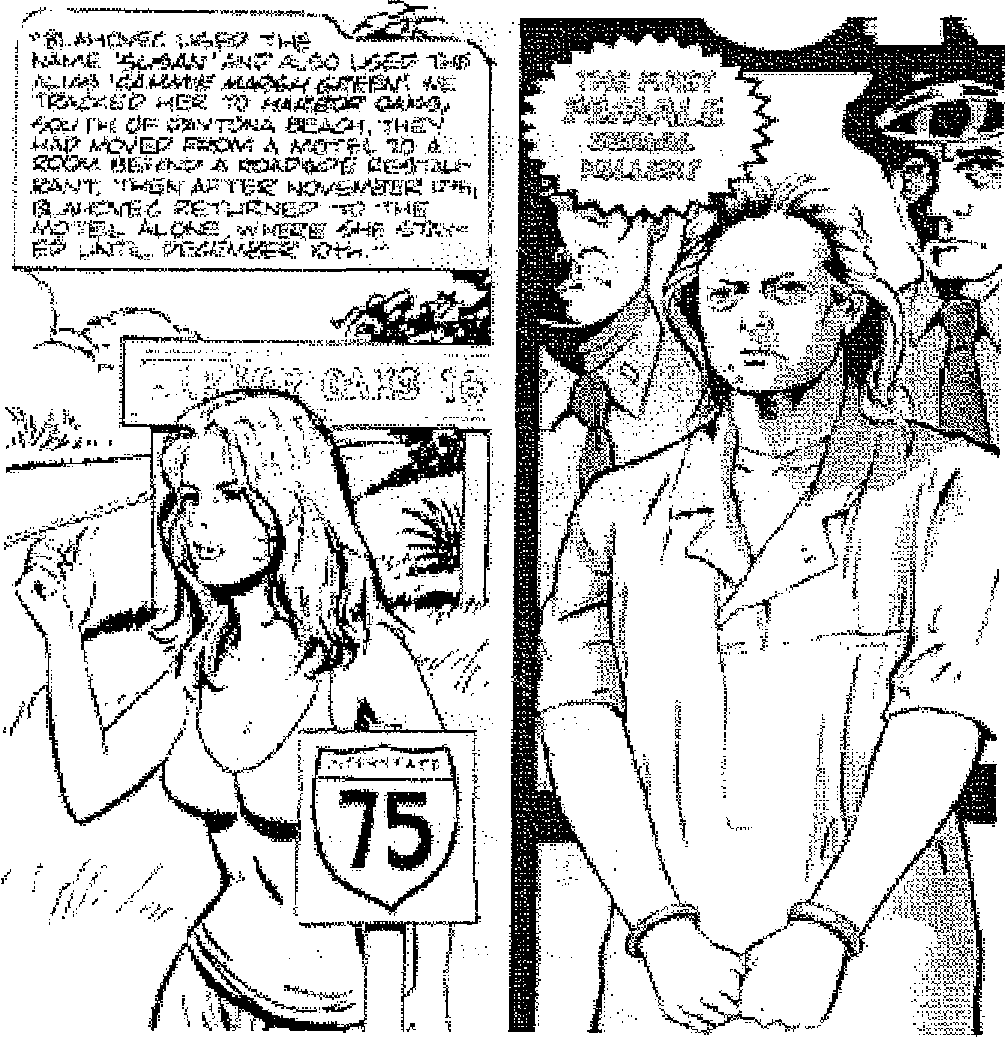

Wuornos’s transformation to a butch killer is apparent in “The Aileen Wuornos Story” in the comic True Crime, published to capitalize on the salacious details of her case.[135] In the account, two detectives discuss the investigation of a string of murders in Florida. Wuornos is introduced to the story while working on the side of the highway. She is depicted as a young, busty blonde in a low cut tank top, attractive but disheveled from a life of prostitution and hard drinking. When Wuornos is arrested, however, she becomes masculine. Even her name changes: instead of “Aileen,” she is referred to as “Lee,” a defeminized version of her name. On the cover of the comic book, Wuornos frowns, flanked by stem guards. She appears haggard and flat chested in a drab unisex prison jumpsuit, holding her shackled hands in fists as she glowers from the page. The phrase “the first female serial killer” is emblazoned above her head, with enlarged text emphasizing the word “female.” Here, Wuornos is unmistakably butch.

Although Wuornos was portrayed as masculine, some accounts explain that she murdered in a womanly manner, such as a 1991 article for the beauty magazine Glamour titled “The First Woman Serial Killer?” The piece focused on Wuornos’s lack of femininity and was written for young, single, heterosexual women, a group highly receptive to warnings about the dangers of appearing unfeminine. Even the title can be read two ways: does it debate her “first” or “woman” status? In the article, Sergeant Munster states that he assumed the killer was female because the victims were shot in the torso, rather than the head. According to Munster, “Women won’t shoot in the head. A man shoots in the head, a man punches in the face.”[136] Wuornos’s firing into the torso, as she did with a majority of her victims, was, according to author Susan Edmiston, a “remnant of femininity” in an otherwise masculine crime of serial killing.[137] Neither Munster nor the author explained how they concluded that the act of discharging into different areas of the body could be gendered, nor did they mention that Wuornos shot her last two victims in the head. In a similar vein, accounts of Wuornos’s crimes cited her use of a .22 caliber gun as womanly as well. In both instances, shooting in the torso and a smaller caliber murder weapon were thought to be feminine because, according to the narrative, a male serial killer would apparently choose a more direct mode of execution.

Lesbian Representation

The discourse of Wuornos’s crimes blamed her sexuality as a motivation for murder. Cinema studies professor Christine Holmlund, writing about female serialist films, argues that “a murmured fear of lesbianism lurks beneath the general discomfort with violent women, and hides behind their portrayal as man-hating feminists or as men....” “Fear” is the key word in this quotation, as Paula Ettelbrick, legal director of the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, explains, “There is nothing more threatening than the thought of a woman who has already chosen not to have any men in her life-—a lesbian—unless it’s a lesbian killer.”[138][139] Numerous accounts label Wuornos as a “man hater,” a euphemism for lesbian. This projected dislike of males was utilized because blaming lesbianism outright would be homophobic and render the hypothesis subject to broader public scrutiny. Retired FBI agent Robert Ressler proposes that Wuornos killed because “there may be an intrinsic hatred of males here, as well as identification with male violence which helped push her across the line into what has been considered a ‘male’ crime.”[140] Forensic psychiatrist Kathy Morall finds an analogous rationale for her crimes:

You might not expect a woman of clear sexual identity to do this. I see her as a woman whose sexual identity is distorted. If this woman’s makeup is such that she takes pride in being masculine, her motivation would be a psychological challenge to the male—“I’m more masculine than you.”[141]

The use of the word “distorted” is particularly problematic: it points to the ambiguity of Wuornos’s sexual identity as a person who had a romantic relationship with a woman, yet had sex with multiple men. Her sexuality could not be narrowly delineated so it was considered threatening in her narrative.

Descriptions of Wuornos treated her lack of femininity as a symptom of her brutal nature. The Glamour article quotes Munster commenting that Wuornos was “dominant and aggressive... carry [ing] herself as a bigger individual than she is.... She was rough- and-tumble from childhood.”[142] He cites her removal of the license plate from Siems’s car with her hands, rather than a screwdriver, as proof of her strength.[143] A local convenience store clerk described Wuornos as aggressive in “the way she carried herself, the way she flexed her muscles. Whenever a nice-looking male customer would come in—I mean, I looked, Ty looked, but [Wuornos] didn’t look. Or if she did, she snarled.”[144] A Vanity Fair article about Wuornos noted that she drank Budweiser and smoked Marlboros, two stereotypically macho signifiers.[145] The media did not view Wuornos’s toughness as a protective measure for survival, stemming from her abusive childhood and her dangerous profession, but as a trait that made her a monstrous killer.

One may find it astonishing that, as recently as the 1990s, a woman’s supposed masculine behavior would be relevant to her crimes. The media’s focus on these details can be understood in the context of a larger backlash against women’s increasing freedom and an apprehension of a crumbling sexual order as examined in the 1991 national bestseller Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. In the book, journalist Susan Faludi criticizes both the media and the social sciences for promoting the theory that the equality women achieved in previous decades brought profound unhappiness to them in the 1980s and 1990s.[146] This anti-feminist sentiment was echoed in the Glamour article, which concluded with an expert’s foreboding warning: given “today’s more aggressive female, the numbers of female murderers will increase during the nineties.”[147] Statements such as this one showed how society projected its anxiety about gender equality onto the subject of Wuornos.

Conclusion

In the 1991-1992 media coverage of the case, Aileen Wuornos was condemned for being white trash, a prostitute, and a lesbian. Together, these traits made her an unsympathetic character in her narrative, even to those who might have championed her rights such as gay, sex worker, or anti-death penalty activists in the years leading up to her execution. Exploring the lack of advocate support in Wuornos’s case, psychologist Robert Butterworth states in a 2001 article for the British newspaper, The Guardian-.

Female killers will always see gender working in their favor if the public perceives them as feminine. We instinctively see women as gentle, maternal, incapable of violence and give female criminals the benefit of the doubt. But when they discard that femininity, and Wuornos did, they lose our built in reserve of sympathy.[148]

Based on Butterworth’s assertion, would Wuornos have been more sympathetic if she could have dismissed her representation and behaved in ways that were more feminine? A useful comparison is thirty-eight-year-old Karla Faye Tucker, who died of lethal injection in 1998, after serving almost fifteen years on Texas’s death row.[149] In 1984, Tucker and her boyfriend, Daniel Ryan Garrett, killed her ex-boyfriend and his girlfriend with a pickax as they slept. Both were given the death penalty, but Garrett died of natural causes in 1994.

Tucker was unrepentant during her trial, claiming that she climaxed each time she axed her victims. In prison, however, she became a bom again Christian and a model inmate. She was soft-spoken and feminine, with well-groomed hair, subtle makeup, and modest clothing. Due to these changes, Tucker won many secular and religious supporters when she began appealing her death sentence in 1992.

Henry Frederick, a court reporter at Wuornos’s case, compared Wuornos to the pious prisoner, “If she was acting like Karla Faye Tucker—sweet, contrite—the public might be more sensitive.... But Aileen Wuornos is no Karla Faye. She’s angry, she’s abrasive.... She’s a vile, sick woman.”[150] The amount of perceived femininity in each woman seemed to influence her public opinion.

A Monstrous Transformation

On the very day of Wuornos’s execution, advance publicity for Monster began.

The film billed itself as “an unlikely story between two misfits”: Aileen Wuornos, played by Charlize Theron, and Selby Wall, the fictional Tyria Moore, played by Christina Ricci.[151] Of the performance, movie critic Roger Ebert writes:

[Monster] refuses to objectify Wuornos and her crimes and refuses to exploit her story in the cynical manner of true crime sensationalism—insisting instead on seeing her as one of God’s creatures worthy of our attention. She has been so cruelly twisted by life that she seems incapable of goodness, and yet when she feels love for the first time she is inspired to try to be a better person.... There are no excuses for what she does, but there are reasons, and the purpose of the movie is to make them visible. If life had given her anything at all to work with, we would feel no sympathy. But life has beaten her beyond redemption.[152]

Wuornos, the subject or person, had seldom been portrayed with compassion in the mainstream media, let alone described as “one of God’s creatures worthy of our attention.” The execution of a media-created monster who embodied society’s anxieties about class, race, and gender was a social exorcism. It was only through her sacrifice that Wuornos gained some type of empathy in her narrative.

Monster opens with Wuornos contemplating suicide beneath a highway overpass, immediately creating sympathy for her. Down to her last five dollars, she heads to a bar where she meets young Selby Wall, who is unfazed by Wuornos’s work as a prostitute. After a series of dates, Wuornos convinces Wall to flee her family and embrace Wuornos’s transitory life. However, the added stress of supporting a girlfriend wears on Wuornos, who must solicit more strangers, some of which are violent. One customer rapes and tortures her, but she shoots him, hides his body, and steals his car. After the murder, which Wuornos initially conceals from Wall, Wuornos tries in vain to obtain legitimate work, but no employer will hire her. The film demonstrates how institutional realities circumscribed Wuornos’s life, making prostitution not a choice, but a way of survival for herself and her new girlfriend.

When Wuornos returns to prostitution, her motivation for killing becomes more unsubstantial as her victims become progressively more innocuous. The film at this point alternates between the homicides and the relationship between Wuornos and Wall. Although they share tender moments like skating together during a slow song at a roller rink, deepening troubles emerge between the pair. Monster posits that Wuornos killed to support Wall, who manipulated her lover into continued prostitution; romantic love becomes the motivation for murder.

Similarly, Monster makes love the reason why Wuornos confessed. After Wuornos is arrested, Wall collaborates with investigators and attempts to have Wuornos implicate herself in the murders during a taped telephone conversation. Wuornos realizes what is happening, and Monster climaxes as Wuornos tearfully absolves Wall of all guilt and takes sole responsibility for the murders.

The Monster narrative is controlled primarily by Charlize Theron. The actress produced the film and used it to elevate herself into greater stardom. Like Academy Award winners Hilary Swank in Boys Don’t Cry (1999) or Nicole Kidman in The Hours (2002), Theron shed her glamour to win the coveted Best Actress award, and Monster’s release, a month before the nominations, was timed to make Theron a contender.

The press on Theron’s performance frequently remarked on her cosmetic transformation into the Wuornos character, as illustrated by these photographs from the film’s website:[153]

An article for the fashion magazine Elle describes the transformation in terms that invoke poverty and decay:

At 27, the long-limbed, lush-lipped, cherubic-faced star has left Hollywood and landed in this derelict Orlando, Florida, neighborhood in a rundown house hear the railroad tracks. She’s gained a good 30 pounds and has let her expensively highlighted hair oxidize into a rusty brownish overgrown shag. Her hyacinth blue eyes have turned dark, cold. She could use a good dentist. Her face is bloated, double-chinned, and appears aged by too much sun, too many cigarettes, and too little sleep. The former camera magnet now knows what it’s like to be unrecognizable in the most painful sense of the word: When people see her coming, they don’t look twice, they look away.[154]

In this passage, the star is portrayed as sacrificing her health, youth, and beauty to assume the role of Wuornos. The film highlights the voluntary mutability of Charlize Theron in relation to Wuornos’s representation. Wuornos’s case not only shows the instability of social identity, but her identity is subject to social constructs projected onto her. On the other hand, Charlize Theron’s social mobility and self-empowerment lies in her ability to alter her representation at will: specifically, to depict herself as Wuornos and then revert to Hollywood glamour. Theron controls and improves her representation by using the subject of Wuornos in ways that Wuornos, herself, was unable.