Mary Warnock

To have or not to have

Abortion: The Whole Story

Mary Kenny

Quartet £9.95

Abortion Practice in Britain and the United States

Colin Francome

Allen & Unwin £7.95 paperback/£18 hardback

Abortion and Woman's Choice

Rosalind Polack Petchesky

Verso £8.95 paperback/£24.95 hardback

Mary Kenny is an experienced journalist, with an accomplished interview technique. She records, in this book, a number of interviews, both with those who have had abortions. and with theorists. She does not perhaps cover, as the blurb-writer claims, "every imaginable issue surrounding . . the subject of abortion"; it is not absolutely the whole story But it is a good read, and oddly soothing. She wanders amiably round the subject, what it's like to have an abortion; whether women choosing abortion are asked if they would consider having the baby and letting it be adopted (they mostly are not asked this); why people decide to have abortions; what various theorists think about it, and so on.

She is not at all unsympathetic, and, on the whole, seems content that women should make their own choices All she demands is that, faced with the decision of abortion, they should take their decision seriously. She realises that nothing will make abortion go away; cannot be abolished But she herself could never think it right! She fully recognises that her judgment is based on sentiment not reason. She does not defend the feeling, but only states that it is strong, and that she will not be moved from it by any argument.

Mary Kenny's book, though in some ways informative and full of moral conviction, is not scholarly or deeply analytic. The same might be said of Colin Francome's Abortion Practice But there is more of real interest in it since it is concerned, not with anecdotal findings, nor with the author's own attitudes, but with a comparison between the prevalence of abortion in Britain and the United States and an attempt to discover ways in which in both countries, abortions could become less frequent. A moral position is thus revealed. It is assumed that it would be better if there were fewer abortions, and it is probably true that most people would make the same assumption.

Francome’s statistics show that the average rate of abortion in the United States is more than twice that in Britain (though the abortions are usually earned out at an earlier stage of pregnancy) He is mainly concerned with teenage abortions, and in order to explain the higher American rate here, he has some illuminating observations on the behaviour of teenage groups in both countries. These are based on what the sociologists call “participant observation " Francome's younger brother was a member of an apparently characteristic group in Swindon; and he himself went to teach tn the United States for a year, and could thus find out about his pupils' goings-on. His work, therefore, has an immediacy and credibility often lacking in the work of academic sociologists

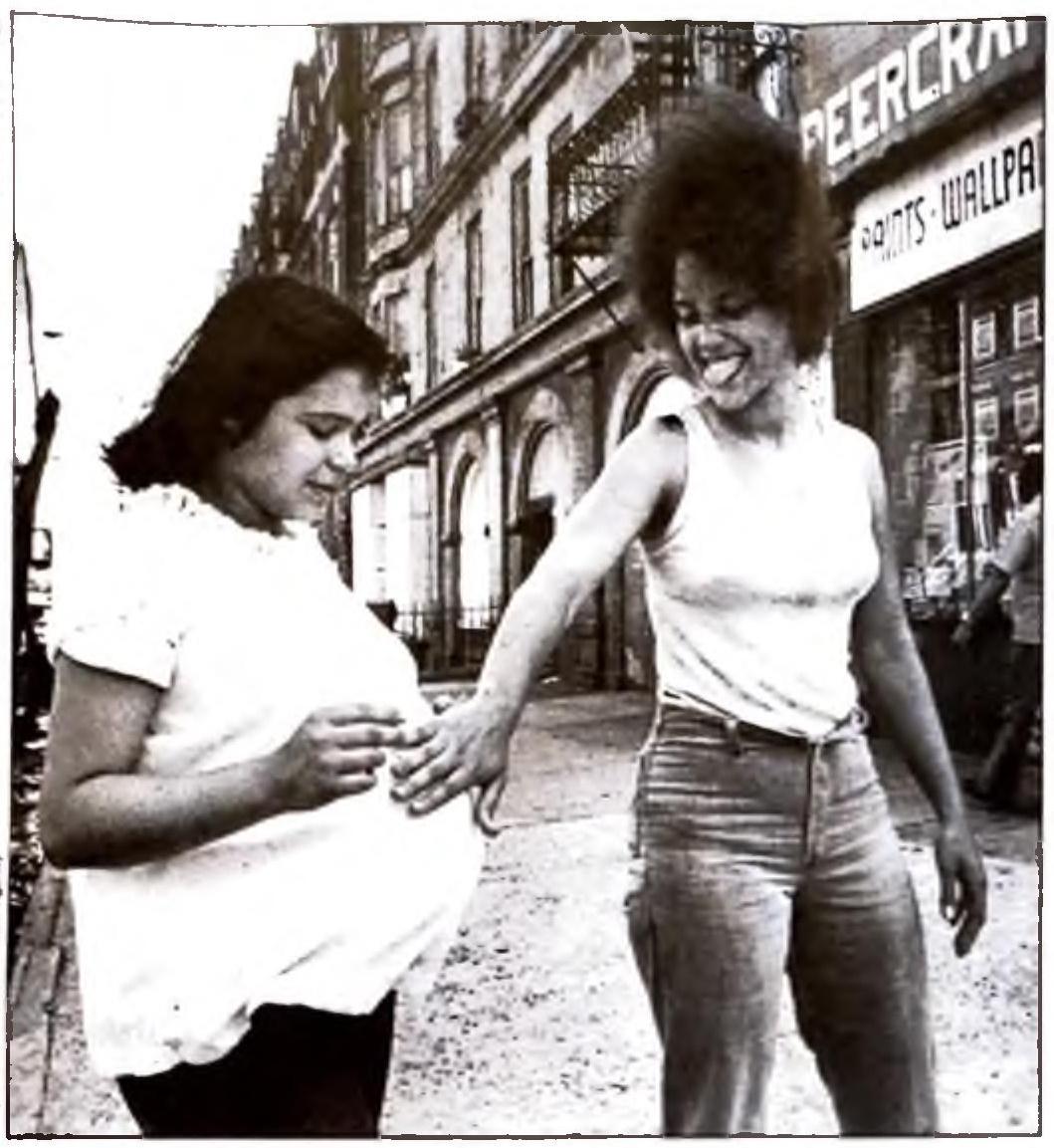

Briefly, he finds that American teenage boys are much more likely to be sexually active than their British counterparts because of a commitment to proving their maleness by forming sexual relationships. The whole culture of “dating” is based on this need. In Britain, though there is much sexual boasting among young males, on the whole their social life is based on the male peer-group or g»m? until they are much older. Even attendance at dances or discos is dominated by the [TEXT OBSCURED] group. Although boys meet girls at these ceremonies, it is quite rare for any real relationship to be established between the sexes.

This means that when sexual intercourse occur, whatever the girl may feel a it, it is very likely that for the boy it will relatively unromantic and experimental makes it unlikely that contraceptive precautions will be taken. It is still difficult for a to take precautions when she does not kn- whether, or when, she will be required t sexual purposes. The American style would make it more plausible for contraception be used, if only it were more readily a cheaply available in the United States.

Francome's solution to the problem of teenage pregnancies and abortion (though he admits that it will reduce, not eliminate abortions) is simple and convincing, more sex-education, and better birth control facilities. The aim is to induce through education greater sense of responsibility, not by preaching chastity, which may well be counter productive, but by early and prolonged discussion, and a far greater encouragement of men and boys to attend both control [TEXT OBSCURED]. Education could, and can, make a huge difference to the attitudes of both boys and girls to pre-marital sex. Francome's book ought to help to convince Members of Parliament that sex education is not a harmful and disruptive threat to The Family.

Rosalind Petchesky’s book was published two years ago in the United States. Its importance for British readers undoubtedly lies in the perceptive and daunting analysis it presents of the New Right, the pro-family politicians. The book is long and pretentious, The reader must struggle with a good deal of feminist-style jargon. There is also a strong identification of feminism with the radical left, the more understandable in the United Stales since state-funded contraception and abortion are regarded as goals only for dangerous socialists, They’re also goals for feminists. But even those who arc neither fully paid-up feminists nor politically far left should be alarmed by the Return to Victorian Values, or Family ideology.

Petchesky shows how the generally liberalised law regarding abortion has been accommodated by the hard “moral" right. Abortion is permitted, but only in a shame-ridden and infantilising way. She quotes a story called “Daddy, I’m sorry" published in Families magazine, where a pregnant teenager throws herself on the mercy of her stern father, is rushed out of town to have her abortion but is nonetheless morally “rescued" by her penitence within the bosom of the family. She returns, the innocent and good little girl, the fallen, but forgiven, Angel in the House. The relevance of such a presentation of Family power to the issues of the Gillick case is obvious.

But the main message of this book is unlikely to be widely accepted. The argument is that women will never get what they need as long as abortion is regarded as an evil; and choice of abortion as a choice between evils. (This, after all, is the meaning of Mary Kenny’s demand that women should see their choice as “serious.") Rosalind Petchesky holds that we shall not be truly free until we stop thinking about individual women facing moral dilemmas, and think instead of women as a group, and the availability to the group of free and non-guilt-ridden abortion.

The trouble is that not even the most ardent feminist can change the fact t la women get pregnant one by one, and that an unwanted or intolerable pregnancy is some thing a woman has to face for herself, an, , ultimately, on her own. That she should be helped; that she should not, as she often is, be made to feel guilty, does not entail that s e has no decision to make. Neither attempting, in the words of President Reagan, to stamp out abortion” by law, nor making it a straightforward service-provision, can alter nature of these facts.