Murray Healy

Gay Skins

Class, Masculinity and Queer Appropriation

Mapping epistemology: who knows?

2. Kids, Cults and Common Queers

Common queers: who are you calling gay?

3. Getting Harder: Skinheads and Homosexuals

‘I like violence, violence and, er, violence’

The masculinisation of gay culture

Fascist symbolism and recontextualisation

7. Real Men, Phallicism and Fascism

Liberté, égalité, homosexualité?

8. ‘The hardest possible image’

‘Oh my God, the skinheads are back’

‘With other gay skins, the sex was very masculine’

9. The Queer Appropriators: Simulated Skin Sex

Foreword to the new edition

One of the most rewarding consequences of Gay Skins being published nearly 20 years ago was seeing my book turn up on a Daily Mail hate list. The paper’s columnist Paul Johnson cited Gay Skins as a symptom of the moral decline of the British intelligentsia in an essay which purported to trace the nation’s descent into barbarism back to the staging of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger in 1956. Johnson argued that the play ‘introduced the era of downward mobility — the deliberate adoption of lower-class standards of behaviour’, and turned to the list of new books by ‘Cassell’s, once a highly respectable publisher of reference and the works of Sir Winston Churchill’, for proof that this era had reached a new low. Gay Skins was one of the titles in Cassell’s new catalogue, and he quoted from the blurb on the back of the book to illustrate his point. ‘Inarticulate, aggro-loving and hard as fuck’ — of course, the Mail printed ‘fuck’ as ‘*’**’ — ‘the mythical figure of the skinhead has embodied fears and fantasies about straight, white working-class masculinity for nearly 3 0 years.’ Appalled that Cassell would dare to celebrate this ‘connection between perverted sex and downward mobility’ (surely Winnie must be turning in his grave), Johnson concluded that in these sick times, ‘seducing a working-class yobbois the dream route of the downwardly mobile middle or upper-class homosexual into the social depths’. The consequence for the ruling classes abandoning their traditional standards in this manner was clear for all to see: ‘Teenage gang rapes, pensioners in their 80s battered to death for a few pence, housing estates terrorised by youth gangs or brutal families and New Age travellers devastating the countryside.’[1]

Aside from being bolstered by a few more stereotypes and end-of-civilisation scenarios, the Daily Mail’s list of folk devils and moral panics hasn’t changed much since then. But revisiting Gay Skins two decades later, I’m struck by how much the cultural landscape in Britain has shifted, or my experience of it at least. There are plenty of quaint, tell-tale phrases and assumptions littered through the text. ‘Illegal videos’, for example; younger readers might need pointing out that in the days before the internet, porn films came on clunky VHS tapes, and anything that showed people having sex was technically banned in the UK.

Reading the book again, I’m surprised by the extent to which homophobic violence was still a constant threat in the mid-1990s, something you had to consider every time you stepped outside. These days I live in south London and lead the kind of life you might expect someone who wrote a book like Gay Skins in his youth to be leading. And while homophobic attacks still happen, the prospect of getting beaten up isn’t something that’s constantly on my mind, or on the minds of any gay men or lesbians I know in my neighbourhood. Walking down the street, you can usually assume that most of the people you pass aren’t particularly homophobic — and even if they are, they won’t do much about it. At least, that’s the assumption I suppose I have the luxury of making. But, particularly in its earlier chapters, Gay Skins takes me back to a time when it was safest to operate on the assumption that all strangers were violently anti-gay until they demonstrated otherwise, and the urgency with which this is apparent in the text came as a shock. The very fact that one account of the ubiquity of the skinhead look in gay subculture identifies it as a strategy of passing speaks volumes.

Another belief central to the premise of Gay Skins that now seems curiously old-fashioned is that clothing could carry very specific ideological or political meanings. While I was writing Gay Skins, Ted Polhemus published his book Street Style, a comprehensive history of youth cults, teds, mods, skinheads, punks et al. Its final chapter heralded ‘The Supermarket of Style’, where individual elements of dress floated free from the contexts that had originally made them meaningful or desirable or cool, becoming available to cut and paste into any number of new assemblages. It was a novel approach to dressing at the time, but of course it’s the dominant mode now. When I wrote Gay Skins I was described on the back cover as a journalist, academic and costume designer’. I was at a sort of career crossroads back then. Gay Skins was one of my final adventures in academia, beginning life as my MA thesis. Soon after I went to work for the street-style magazine The Face and from there became a fashion journalist. There I witnessed the rise of the fashion stylist in the late 1990s to its current status as one of the chief architects of the promotional imagery that saturates British culture. From pop stars to prime ministers, pretty much every public figure employs a stylist now. And in the age of the stylist, the history of fashion has become one huge supermarket, to borrow Polhemus’s term, where the shoppers have limitless credit and the shelves never run dry. The once arcane clothes and codes favoured and created by working-class delinquents are now part of the visual language of luxury fashion houses. As I write, it is a year since Givenchy, a label whose menswear draws in large part on a well-informed awareness of youth street culture, offered a very accurate re-presentation of a black MA-1 flight jacket, that staple of the skinhead wardrobe, with a £1,000 price tag — albeit with the tartan lining of a jacket that we in the south of England once called the Harrington, which thanks to the internet we now refer to more accurately as the Baracuta G9, cut and pasted onto its insides. And next season, Saint Laurent’s menswear collection offers a fusion of rockabilly and glam rock designed by someone who evidently has an encyclopaedic knowledge of the history of both youth cults.

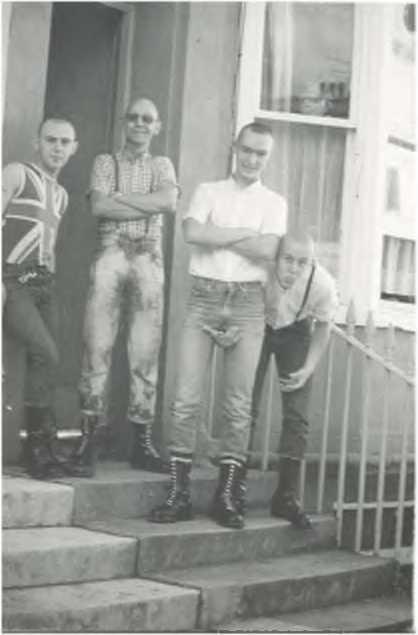

Twenty years ago, such mixing and matching would have looked like a case of profoundly misunderstanding your source material. Clothes were part of a code that allowed you access to and acceptance by a subculture: get the combination wrong and you were locked out. Wearing the wrong kind of bomber jacket, or the wrong colour of boot, simply advertised the fact that you didn’t know what you were doing — and knowledge was a key part of belonging. The clothing was part of a broader collection of elements — the genre of music you listened to, where you hung out, the way you danced, the words you used — where it was vital to get it right. Even then, it wasn’t enough simply to do your research (and that was hard enough, as there were no books to guide you, let alone any internet where the blogs of obsessive devotees might anatomise the subculture for you) and get it right. Every time you stepped out in those clothes, you offered yourself to be judged by other members of your cult as to whether you had earned the right to wear them, as to whether or not you qualified as a true skinhead, or punk, or whatever. Furthermore, you could expect to be punished by rival tribes, to which your appearance was an affront and a challenge.

Today, it’s hard to imagine that you routinely ran the risk of taking a beating for the way you looked, for the subcultural affiliations advertised by your clothes. For the most part, clothes are now interpreted solely in terms of aesthetics and economics — ie, whether they looks good and how much they cost. It still never ceases to amuse me how the meaning of ‘street style’ has changed so completely as a consequence. A ‘street style blogger’, for example, is someone with a camera and a website who posts pictures of rich kids wearing stupendously expensive high-end labels (bought from the same department stores their parents shop in) and of powerful fashion stylists with six-figure salaries, snapped outside fashion shows. Going by this definition, the ‘street’ in question is Bond Street, and about as far as you can get from a thug in a carefully coded uniform picked up from workwear shops and military suppliers. These days, clear and potent ideological and political meanings only appear to be ascribed to clothing when it is perceived to belong to a religious tradition. But then, they didn’t call them youth cults for nothing.

1. Introduction

‘I hope you don’t mind me asking, but just why are you interested in gay skinheads?’ It’s a fair question that a number of skinheads, who have found themselves looking down the wrong end of my microphone, have felt the need to ask me. They were understandably wary of this nosey stranger with a list of questions, a tape recorder and an appearance about as far removed from ‘skinhead’ as possible. I must have looked suspiciously like an outsider sniffing round their subculture in order to debunk it. Given the political debates that have raged over the presence of skinheads in gay subculture for at least the past fifteen years, it would not have been the first time.

Initially I wasn’t interested in skinheads at all. The work that was to become Gay Skins began when I was attending an MA programme at Sussex university entitled Sexual Dissidence and Cultural Change in the early 1990s, and was inspired by a college tutor’s challenge to disprove an assumption that was fairly commonplace in academia at the time: that homosexual identity was something few working-class men in Britain had access to before 1970 and the advent of the ‘Liberation’ era. Challenging this was difficult: quests through reading lists revealed a conspicuous absence of material on working-class gay men. I was disappointed, but not surprised. The ruling classes write history — or the authorised accounts, at least — and that goes for the history of sexual dissidence too. For very obvious reasons, homosexual cultures needed to remain inconspicuous until at least the partial décriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967, and work on recovering those unwritten histories was just beginning. But sourcing first-person accounts wasn’t an option for me at the time, not least because I knew hardly any gay men over the age of 25. My only recourse then was academic speculation.

I found hope in The Leather Boys, a novel published in 19 61 about two men in a biker gang who have a sexual relationship. This led me to investigate the possibility that delinquent working-class youth cultures might have allowed space for queers not only to have sex but to form an identity that incorporated a consciousness of both their class and their queerness. Parading their non-conformity through style, and consequently creating new forms of masculinity, pretty much every male working-class youth culture in the postwar period held queer potential, from Teds to ravers. The one exception was the skinhead, almost a cartoon caricature of conservative masculinity, and an identity that had become closely associated with far-right politics in the 1980s. All the more curious then that by the early 1990s the skinhead look has become so prevalent on the gay scene in Britain. It’s this apparent paradox that lies at the heart of my interest in gay skinheads.

I’m not interested in skinheads for the reasons you might think. You’re not the only one: a lot of gay men suspect this explanation is disingenuous. They think they know the real motive. A common reaction to my work has been, ‘So you’re writing a book on gay skinheads? Bet you’re enjoying the research? Nudge, nudge, wink, wink, say no more. And that’s the trouble: so much more needs to be said. But it never is, because within gay subculture, that gay men should find the image of a skinhead a turn-on is so fundamental that it goes without saying. The assumption is never questioned: and when I have questioned it, I’ve been told that ‘it’s simply common sense that a gay man should fancy a real man’. And already, within that commonplace, throwaway refusal to explain masquerading as an explanation, there are all sorts of loaded, contentious terms that need unravelling.

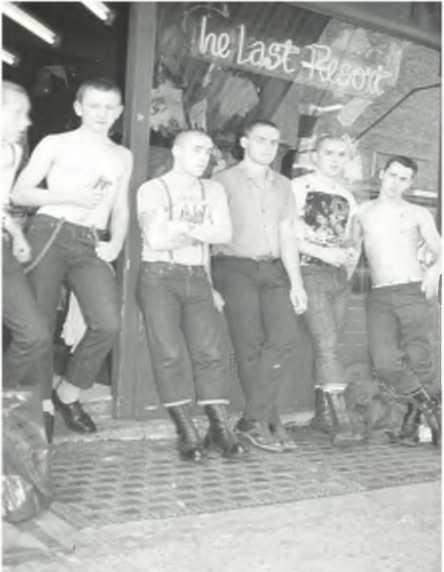

Because he is so sexy (or so I’m told), the skinhead has become without doubt a homosexual phenomenon. Skinhead identities have become increasingly popular among gay men since the mid-1980s. At the time of writing — summer 1995 — there are five venues in London alone that cater specifically for gay men who identify as skinheads: The Anvil, the London Apprentice, the Coleherne, the Block and the sole exclusively skinhead club. Silks ’95. There are established gay skinhead networks in other cities too, most notably Birmingham and Manchester. But London boasts the oldest, most diverse gay skinhead scene — not surprising, considering that it also has the biggest gay scene anyway and is where the skinhead first emerged. In addition, there are national gay skinhead social organizations, Skin4Skin and the Gay Skinhead Group. In its personal ads, the weekly gay listings magazine Boyz has included a column specifically for skinheads, ‘Boots and Braces’, since its launch in 1991. Furthermore, skinhead imagery extends its influence well beyond the distinct minority of gay men who would describe themselves as skinheads: sexual fantasies about skins feature prominently in porn mags, illegal videos and ads for sex chat lines.

In addition to those who proclaim themselves to be skinheads, there are many more wearing the same gear who don’t. Scene wisdom holds that dressing like a skinhead will dramatically increase your chances of finding sex, and certainly anecdotal evidence suggests there’s some truth in this. While I was writing this book, a thirty-year-old colleague of mine shaved off his peroxide buzz-cut and shed his favoured designer clubwear in favour of a Ben Sherman short-sleeved shirt, braces, bleach-splattered jeans and ox-blood DM boots to guarantee him entry to a men-only club that was holding a skin night. An Essex boy, he hardened his accent and perfected the stance. When he recounted his night out to me the following day, he acknowledged this performance as drag; but he had looked the part. ‘They were queuing up in that back room!’ he exclaimed in disbelief; it wasn’t as if he hadn’t been notoriously popular in such environments beforehand. ‘And the harder I acted, the stroppier I got, the more they loved it!’ Such were the benefits of being a skin that, although he disliked the look from a stylistic point of view, he kept the shaved head so he could slip into his skin drag whenever he felt the need.

And then there’s the third constituency of gay men who dress like skinheads: the ones who don’t even realise it. About the same time my colleague was first discovering the joys of sex in skin clubs, I ran into an old friend I hadn’t seen for nearly five years; he was now twenty-five and a social worker. Whereas he had once favoured the anti-style aesthetics of the student-activist, he now had a shaved head and was wearing a bottle-green Fred Perry, red braces, rolled Levis, black DM boots and a green MA-1 flying jacket. When I asked him whether I could interview him for this book as a skinhead, he protested, ‘But I’m not a skinhead. I dress like this because I’m a gay man. It’s sexy and it turns queens on!’

But what is it about a cropped scalp, rolled-up jeans, a flying jacket, and Doc Marten boots (to take one incarnation of the skinhead uniform) that encompasses an unquestionably sexually desirable masculinity for so many men? And here again as an outsider, as one who has never felt this attraction, I am well placed to ask this question.

Why do so many gay men, consciously and unconsciously, look like skinheads? This particular youth subculture seems to have informed the development of gay male presentational codes more than any other. Just go into any gay bar and tick off the elements from a skin wardrobe; the common urban gay uniform has consisted of Doc Martens, Levi’s jeans, T-shirt, polo shirt or short-sleeved gingham shirt, bomber jacket and cropped hair since the mid-1980s. It’s hardly contentious to suggest that this uniform is derived from skinhead culture. So widespread are these elements in British urban gay networks that they have ceased to signify skinhead, sending out the message ‘I am gay’ instead. So it isn’t always easy to maintain a distinction between gay skinhead and broader significations of gay identity at a purely stylistic level.

Tracing the history of the circulation of skinhead codes on the gay scene is therefore particularly difficult, but presumably there was a time when the sight of skinheads on the scene was so uncommon as to be conspicuous. When did gay men start using elements of a teen subculture of the late 1960s? Did they hijack a look after it went out of fashion? Or, given that the first wave of skinheads comprised a walking assemblage of macho signifiers that gay men had already come to fetishise, were gay men partly responsible for the creation of the look in the first place? In fact, were there gay skinheads right from the start?

Straight expectations

At the start of this project, the ubiquity of skinhead codes in gay subculture rendered them unremarkable — indeed, they barely read as ‘skinhead’ any more. But I can remember being shocked the first time I happened across a gay skinhead, or at least a gay man who looked like one. It was in my early teens, on Channel 4 where I discovered the dancer Michael Clark. He had a poofy job, a bit of a poofy voice, but he could behave like a bit of a lad and dressed, at various times, like a punk and a skinhead. I was amazed. Straights might actually be scared of him!

Of course, it was a naive reaction. But just as naive was my later assumption that, by 19 92, everyone had become familiar with the existence of gay skinheads. In stark contrast to those who were aufait with gay male subculture, uninitiated heterosexuals have been puzzled by my project: ‘Gay skinheads? Gay? Skinheads? Are there such things?’ They assume that the skinhead and the gay man are unrelated species. If the existence of gay skinheads is beyond question for gay men, it’s still out of the question for the subculturally uninitiated.

Consider Peter Tory’s review of Skin Complex, a TV documentary about gay skinheads shown on Channel 4’s lesbian and gay series Out in July 1992:

JUST OUT TO SHOCK

Channel 4’s programme, Out, the series for and about homosexuals, cannot often be recommended viewing for those of a nervous disposition. This week’s offering would certainly have frightened old ladies. And pretty boys too, no doubt.

The question was asked: have gay men gone too far in their quest for the ultimate macho sex image? The answer from those who are not of the inclination must be yes.

Gay men, according to Out, now favour the skinhead look. They parade about, virtually cropped and with rings in their lobes, looking as though they would like to tear the noses and ears off old-age pensioners.

The majority, surely, find aggressively overt gay men offensive. And the majority, of course, find skinheads equally so. Put the two together and you have a real fright.

We can only hope that gay men one day revert to wearing suits and ordinary hair-cuts like the rest of us. Then Channel 4 can follow its programme, Out, with another one — perhaps — called In Again.

This columnist for the Daily Express has had a frightful shock. Gay skinheads shouldn’t exist, but they do. They shouldn’t exist because the common understanding of masculinity to which he subscribes posits ‘the skinhead’ as the very opposite of ‘the gay man’. Press coverage of what started out as just another teen subculture in the late 1960s has created a social mythology around skinheads to which a conservative notion of authentic masculinity — working class, socially fixed, physical, brutish and violent — have become attached. In contrast, ‘gay man’ is predominantly viewed in mainstream culture as unnatural/ effeminate, middle class, socially mobile, cerebral or cultured and physically weak. The two are placed at opposite ends of the political spectrum also, skinheads associated with an affinity for the politics of the far right (a consequence of the way fascist groups set out to recruit them in the early 1980s) and gay men with the left (again, an understandable assumption given the left’s championing of gay rights). Restricted by such reductive definitions, the categories ‘gay man’ and ‘skinhead’ define themselves against one another. They operate as polar opposites — both reminders of what men shouldn’t be. They demarcate the unacceptable opposite extremes of masculinity (for this reviewer, both are ‘equally offensive’) and thus stabilise the area of accepted masculinity in the space between them. That the two poles might actually converge in a single identity disrupts the dominant expectations of male behaviour. Hence ‘put the two together and you have a real fright’: the knowledge that gay skinheads not only might exist but are in fact common short-circuits accepted beliefs about what constitutes ‘real’ masculinity.

Of course, Tory doesn’t want to have to think about skins, queens or the idea that masculinity might not be in any sense real anyway, so the assump-tions mapped out in the accepted territory between ‘gay’ and ‘skinhead’ are never explicitly stated. It goes without saying, and these assumptions need to be left unsaid. To reiterate the ‘common sense’ assumptions about masculinity would be dangerous, because the fact that the gay skin does exist despite them risks exposing their inadequacy.

So instead the reviewer redeploys old, familiar stereotypes: skinheads are scary creatures that tear the noses and ears off old-age pensioners, and gay men are effeminate ‘pretty boys’. But even these are undermined: where once he could assume that there could be only one kind of poof, one kind of skin, he has to acknowledge that there might be poofy skins and hard queers. This unfamiliar form of homosexuality revealed in the gay skin, one which is ‘aggressively overt’, leads Tory to seek solace in a more reassuringly familiar model: homosexuality safely contained in the bourgeois politeness of the suit, where it becomes invisible (‘in again’).

The gay skinhead then embodies a troubling contradiction that threatens to undermine masculinity. This is because masculinity exists within the fragile interplay between the homosexual and what Eve Sedgwick has termed the homosocial: the consolidation of masculinity through the grouping of men together, the unity of gender sameness in opposition to the absent, abject other of woman. Male homosociality is expected in certain environments (the football terrace, the snooker hall) and rituals (stag nights) and enforced in institutions (the military forces, sport). Many gay men’s unhappy experience of games at school, which in many educational establishments is now the only occasion in which the sexes are separated, may lead them to suspect that their purpose has nothing to do with physical fitness or teamwork, and everything to do with reminding you that you are a man, teaching you what is expected of you as a man, and testing how you meet those requirements by placing you in competition with other men. It is instruction in homosociality and it is a Good Thing, unlike homosexuality, against which it has to maintain its difference. Much cultural effort is devoted to concretising the distinction between the two, which is why so much anger and embarrassment accompany debates about gays in the military, rumours about gay football players, and so on. The discovery of the homosexual within homosocial institutions threatens to sexualise the whole environment as individuals are eyed with mistrust — everyone is potentially queered, and being a man’s man might arouse more than mere suspicion. Hence the masculine rituals of urinal etiquette: always look straight ahead, keep words to a minimum, don’t talk to strangers, and keep your movements as macho as possible. Knowledge (and indeed experience) of cottaging is common enough for men’s toilets to be a queered space, and the potential for homosexuality to rear its ugly head in this homosocial environment is disavowed by shows of manly hostility.

As if femininity were a symptom of homosexuality; and this is precisely the problem. Ostensibly homosexuality functions as the inverse of homosociality, so the two can never be present at the same time. This is predicated on the invert model of male homosexuality — female souls in male bodies manifest in feminine behaviour — so when gay men appear within the hypermasculine environment of the homosocial, gender expectations are troubled. When a safely homosocial icon such as the skinhead — masculine, gang-based, all lads together — is revealed as a gay subcultural identity, homosexuality and homosociality become dangerously entangled. This is hardly a surprise for those gay men who for decades have moved in cultural environments where homosociality is strictly enforced in order to articulate their homosexual identity — in other words, queens cruising in men-only clubs. For some straight men, such as the Daily Express’ TV reviewer, the realisation that homosociality might be something sought out by homosexuals is a ‘real fright’. The proximity and congruency of homosexuality and homosociality becomes horrifically apparent: queers want to be with ‘real men’, and queers even look like ‘real men’ these days, so being a ‘real man’ is no longer a defence against accusations of queerness...

The confusions in Tory’s review reveal the knock-on effect that the dissolution of homosocial/homosexual has on private/ public. Sexuality is supposed to be a private matter, and Tory claims he wants homosexuals to go ‘in again’ — to confine them to the closet, because what two men do in private is not his concern; privacy affords this privilege. He proposes that individuals in the public space wear a uniform, a suit. This would deny homosexuals a social identity by erasing markers of homosexuality in public, and deny the difference of their private lives, so he never has to think about it; they will all look like heterosexuals. But he has identified skinheads as straight, so gay skins can hardly be accused of publicly marking their difference: by his logic, gay men have actually satisfied his demand of going ‘in again’ by becoming skinheads. And yet he damns them for being ‘aggressively overt gay men’. In fact, despite what he says, what Tory really seems to want is to confine gay men to the closet of the less troubling effeminate model — ‘pretty boys’. Closets don’t so much hide the homo-’Sexual as pronounce the homosexual’s confinement. It’s the unexpected ease with which homosexuals slip from the private and colonise the public space (the skinhead is a street identity) that alarms him. In short, the gay skinhead has made nonsense of ‘common sense’ (heteronormative) understandings of masculinity.

Unidentifiable bodies

The same confusions at work in the review of Skin Complex were evident in a news item in the Sun newspaper nearly twenty years earlier. On 12 May 1973, under the headline ‘THE MYSTERY MAN IN LEATHER’, the tabloid reported a suspected gangland murder after a body was washed ashore in Rotherhithe:

The strange life of Wolfgang von Jurgen was as full of mystery as his death.

Police had him on their files as Michael St John, small-time London crook. And when his hand-cuffed body was washed up on the Thames shore they treated the case as gang-land murder.

But his death came as a shock to neighbours in Stratford, East London, who knew him as a young TV actor and drag artist.

...Von Jurgen was the name he used on stage — and he told his landlady, in his ‘posh, educated voice’, that he was German.

But he was really born in Stoke Newington, North London.

And in his secret life of petty crime he used at least two further aliases: Bernard Cogan and Anthony Cohen.

The report goes on to describe the suspected murder victim as leading a ‘bedsitter life’. According to his landlord, ‘He lived on his own and we did not see many of his friends. We never saw him with any girlfriends.’ The landlord’s wife added, ‘His two close friends were Terry and Mark, who took part in the drag act with him.’ Are these pieces of ‘evidence’ provided to suggest that the man in question was a homosexual?

The report goes on: ‘Recently, Wolfgang started wearing expensive leather clothes. The red-painted walls of his flat were covered in pictures of film stars, including Steve McQueen in motorcycle gear.’ This might appear conclusive evidence to the modern-day reader. But although by 1973 leather had acquired kinky connotations in the mainstream, were these details intended, and could they be guaranteed, to signify queerness to straight readers of the Sun? The photo accompanying the piece showed the mystery man baring his muscular torso, sporting cropped hair with long sideburns, and braces dangling off his jeans: a skinhead. His appearance, along with his wardrobe of leather, gang-land connections and bachelor lifestyle, would seem to have marked him out as conventionally masculine in a way that contradicted the homosexual hints provided by his biographical details: otherwise, why would a neighbour have felt the need to insist, ‘He was a cheeky, jovial character — certainly not a Hell’s Angel’?

In fact, as I discovered in the course of writing this book, Wolf, as he was known to other gay skinheads, was a well-known face on the emerging macho/fetish scene of the late 1960s and early 1970s. But such knowledge was not available to straight (and indeed many gay) readers at the time. So while these details add up to an identity that appears coherent and familiar to many of us in the 1990s, they remained conflicting and contradictory for the Sun reporter. Unable to be reconciled within one being, they constitute a schizophrenic nonsense: just as he has an excess of names, so he has an excess of inconsistent character attributes. If he’s jovial then he can’t be a Hell’s Angel; if he’s a drag queen, he can’t be straight; if he’s a hardened criminal, he can’t be gay; and if he’s any of these things, he cannot be — and, conspicuously, is not — described as a skinhead, even though that’s exactly what his picture announces him to be.

The essentialist discourse of the centred individual still dominates common understandings of identity: individuals are required to be com-prehensible as consistent personalities, their biographies neat, linear narratives. Wolf’s frustration of this requirement as a gay skinhead meant that he could not be conceived as a ‘real’ person. Hence the report’s curiosity and confusion: the mystery was not so much who as what he was. So even when the unidentified body washed ashore on the south bank of the Thames was positively identified as Wolf’s, as a gay skinhead he continued to remain an unidentifiable body. Under the excess of names and identities, irreconcilable within the parameters of heteronormative organization, the ‘Man in Leather’ remained a ‘mystery’: ‘So just who WAS the man whose body, after at least a week in the water, was pulled ashore at Rotherhithe?’

In Bodies That Matter, Judith Butler analyses the way in which bodies become real, achieve materiality, through their sexing: ‘Sex is one of the norms... that qualifies the body for life within cultural intelligibility.’[2] Through this she exposes the false dichotomy of nature/nurture which has dominated debates on gender and identity for the past four decades — ‘Are men born or made?’, ‘Is femininity innate or learned?’, ‘Is there a gay gene?’ Gender is neither an essence expressed through the body, nor a cultural construct written upon the ungendered site of the body — the body seems to be always/already gendered because it is only intelligible, it comes to be a body, through its gendering: ‘The body signified as prior to signification is an effect of signification’ (p. 30). In the Sun’s account of his life (or lives), the man who was Wolf fails to materialise.

For most of the twentieth century, homosexuality has been understood according to the invert model, which feminises male homosexuals. To put it crudely: men cannot really be sexually attracted to men, so homosexual men must exist as women in some respect. Confined to the open closet of the effeminate model, the homosexual is conspicuous; any movement beyond this therefore renders the homosexual invisible, as his homosexuality is culturally unintelligible. The masculinising discourse of the gay skinhead is not one of the norms by which homosexuality can be understood by straight society.

Butler describes how the exclusionary matrix of heterosexual imperative creates ‘unlivable’ and ‘uninhabitable’ zones of social life against which the subject constitutes itself, and she concludes that it may be precisely through practices which underscore disidentification with those regulatory norms by which sexual difference is materialized that both feminist and queer politics are mobilized. Such collective disidentifications can facilitate a reconceptualization of which bodies matter and which bodies are yet to emerge as critical matters of concern.

This is precisely the kind of collective disidentification that I believe the gay skinhead represents. The heterosexual imperative is a regulatory norm that preserves the cross-gendered nature of sexual desire by holding that gay men love men because internally they are inherently feminine. Skinheads emerged in the East End of London at the very time when gay politics on both sides of the Atlantic was mobilising various disidentifications with this invert model; for gay men in England, the skinhead represented the most potent representation of ‘authentic’ masculinity available. What the gay skinhead is then is a mystery man: an unidentifiable, culturally unintelligible body identity precisely because masculinity as it was understood should have ruled out its emergence. So ‘gay skinhead’ must be left unarticulated (and Wolf is labelled neither ‘gay’ nor ‘skinhead’ even though both possibilities are presented as likely in the Sun report) or willed away (as Tory does in his Express column: gay skinheads should go Tn Again’; at least ‘pretty boys’ uphold the heteronormative matrix) because the very term demands a reconceptualisation of bodies that matter. Tory’s distaste in his column is due to the fact that his (common) understanding of homosexuality should preclude the existence of gay skins. But not only do they exist, they have alerted himto their existence; they have become intelligible — they matter. Nineteen years divide the two newspaper reports. What is remarkable is that it took so long for the gay skin to materialise in the straight press.

Mapping epistemology: who knows?

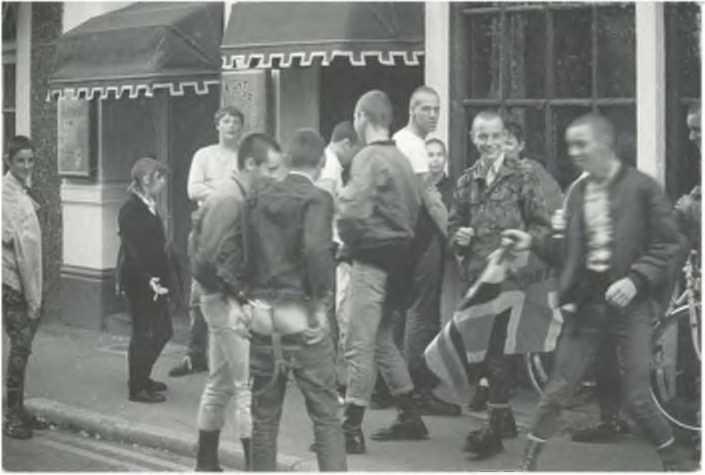

In 1986, the Guardian newspaper ran a TV advertising campaign in which, identifying itself in opposition to the strong rightwing agenda informing the editorial policy of other British newspapers, it sold itself on the grounds of its objectivity. It sought to demonstrate its broader perspective with a commercial that, filmed in black and white, showed a skinhead running down a street of Victorian terraced housing towards a man in a hat, suit and overcoat. Coded as a businessman, the expectation that he will be assaulted is reinforced by his raising of his briefcase as a protection against the oncoming skinhead. A final sequence, filmed from a different angle, sees the skinhead pulling the businessman out of the way of bricks falling from a building site. ‘It’s only when you get the whole picture you can fully understand what’s going on,’ assures the voiceover. It ends with the caption ‘The Guardian: the Whole Picture’. Aha, appearances aren’t always what they seem; you thought that skinhead was a villain when in fact he’s saving someone’s life.

The advert exploits the skinhead’s unambiguous significance. The monolithic status of the skinhead is such that it can be assumed he will be read in only one way, allowing the advert to counter this sensationally with an unexpected action. The shock, or indeed plausibility, of this revelation depends on the subject position of those watching the ad, of course. But even the ad’s makers are unaware of the full extent of the skinhead’s polyvalency. While a Telegraph reader might snort indignantly at the implausibility of a skinhead do-gooder, and a Guardian reader feel a warm glow at seeing prejudices being questioned, some queen, who maybe reads the Sun, might absentmindedly catch the ad and think he’s just spotted his boyfriend on the telly.

This Guardian commercial hadn’t anticipated the number of ways in which a skinhead might be read. By the mid-1980s, elements of skinhead dress were already so ubiquitous on the gay scene that they were ceasing to signify ‘skinhead’ and starting to signify ’gay’ instead. But such knowledge is restricted. One’s social position dictates the breadth of the ways of reading ‘skinhead’. Even now, a decade on, gay skinheads are still invisible as gay men to many straight people.

‘I don’t think the general public know about it at all at the moment,’ says one gay skin I interviewed in 1995. ‘I think they’re quite shocked to discover gay skinheads. My boyfriend’s very, very out, very bold, and if he feels affectionate, he’ll show it wherever we are. We were holding hands in Oxford Street today, in our usual skinhead gear, looking straight I suppose, and we got a few strange looks. We’ll actually sit on the bus holding hands and people are shocked. I still feel slightly conscious of it, but he doesn’t at all, he’s totally relaxed. Once these straight lads got up to get off, and the last one noticed, and he said to his mate, “You see them geezers on the back seat? They’re holding hands!” And they were quite shocked. We found that funny.’

The invisibility that skinhead clothes still seems to provide in the mainstream may be one of the factors that renders it attractive to gay men. Two gay skins interviewed on Skin Complex spoke of the protective cover their clothes provided. ‘The fashion skin is replacing the classic clone look and maybe the leather look as well’, observed one, for reasons of ‘security... if you walk out of a club looking like a skinhead, you’re not going to get anyone coming up to you and calling you a poof and a queer... the last thing in their thoughts is a gay, a poof.’ Another agreed: ‘A lot of it’s self-defence.’

This can be politically problematic, of course. Passing as straight frustrates the requirements of gay liberation that homosexuals be visibly identifiable. Any act which refuses to be so might be symptomatic of a desire not to be gay; self-oppressive, even. But even gay skins aren’t sure how (in)visible they are as gay men.

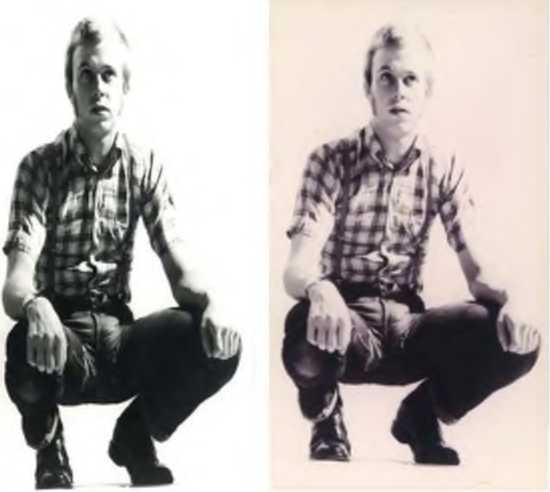

When I interviewed Chris Clive, who ran the Gay Skinhead Group until his death in 1995, he maintained that, while the image did provide some protection from queerbashing, this was a by-product, a secondary benefit, and not a primary motivation. But there was a hesitation in his words, an uncertainty predicated on time and place. ‘You walk down Old Street from the London Apprentice — maybe not late at night, because then people might know where you’ve been... well, certainly in any other town — and people won’t try and attack you.’ His correction was significant: the London Apprentice is a gay fetish club in East London, and he assumes there is enough knowledge in the local straight community for his skinhead appearance to be read as gay. Or at least, there might be. One question central to this entire project is, how do different people read ‘skinhead’, and in how many ways? This is still debatable among gay skinheads themselves. These communities of knowledge don’t map neatly on to ‘gay ghetto’ and ‘straight mainstream’. Age, geography, time, and wilful ignorance all play a part in determining who can read.

Chris went on to say.

If I saw a cropped-haired guy, a skinhead, in Guildford, for instance, I’d assume he was straight and a proper skin. If I saw him on the Tube or on the escalator and he kept looking round at me. I’d know he was gay. London’s a bit different because there’s more around. Straight people, a lot of them wouldn’t really know a gay person unless he started waving his arms about, so I think most straight people if they saw even a gay person with cropped hair and boots and things on, they’d probably assume he was an out and out violent skinhead. And the further north you go, the more people assume that you are a typical, violent skinhead, I suppose, a bovver boy.

He felt that in London, being recognised as gay through skinhead codes was a signal to other gay men, and straight passers-by too; but the generally liberal, cosmopolitan tone of central London meant that this did not make him a target of homophobic abuse.

The extent to which geography dictates people’s ability to decode ‘skinhead’ as ‘gay’ is illustrated by the experience of one Brighton-based skin:

It seems the hassle you get is sometimes anti-gay in nature. It’s not like London. This is a small provincial town. It has a mixture of London indifference, laissez-faire attitude, and small town mindless stupidity. On Friday nights round the Steine, you get gangs of straight lads waiting for people to hassle.

Straight people in his town, he believes, are likely to be both aware of gay skinheads and homophobic.

But the skinhead is not just any old straight signifier: in the popular imagination it has a long history of association with extreme masculinity and violence which, in the late 1970s, was exploited by far-right political groups. So there are further questions to ask about who can afford to read the skinhead as anything other than a threatening mode of hard masculinity that is significantly white. Given the skinhead’s association with violence against communities on the grounds of racial difference, who can afford to read the skinhead as anything other than a racist fascist? And given that there are still those who engage in homophobic violence who claim that identity, can white gay men be so ambivalent to the social and political meanings of skinhead imagery? Even those who might wish to argue that the skinhead’s reputation for fascist allegiances is undeserved would have to admit that the image is not entirely uncontroversial or unproblematic.

The variations in homosexual (in)visibility that gay skins today represent highlight the difficulties in recovering the histories of people who articulated some sense of same-sex attraction in the past. If a subculture as established as gay skinheads can still pass invisibly to most of the population today, how much more difficult it is to recover the histories of such unreadable figures. It is not simply a matter of whether identities have been suppressed or hidden by a homophobic establishment. Given the violence with which homosexuality has been policed, it was in some people’s interests to compose a self-presentational strategy that signalled to those with whom they shared an identity without alerting the attention of others. If these men didn’t want to attract the attention of the contemporary press and police, how much harder for the historian thirty years later.

Dangerous knowledge

The communities of knowledge demarcated by those who read skinheads as gay are tellingly self-contained. This may be because the challenge that the gay skinhead represents to traditional masculinity is too difficult to engage with for anyone who has some investment in those traditions. There may be another, related reason. It was Jean Baudrillard who posited the transmission of information as viral. Homosexual knowledge is perhaps contaminatory; it implicates the bearer: ‘It takes one to know one’. Much of the history of homosexuality has been written in double entendre, as much to protect the writer from accusations as to protect the reader from dangerous knowledge.

The sharp delineation of homosexual knowledge has been conspicuous since the inception of homosexuality (the term was coined in the mid-nineteenth century), and this may be for similar reasons of wilful disavowal. Double entendre has proved a vital means of communication for gay men, but it also provides straight commentators a latex glove with which they can handle such hazardous knowledge. In his consideration of the life of Oscar Wilde, Neil Bartlett refers to Charles Whibley’s review of The Picture of Dorian Gray for the Scots Observer in 18 90, which claimed the play was intended to be read by ‘outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph boys’. That is, queers: the phrase referred to a newspaper scandal about a post office clerk who seduced young messenger boys and recommended them to a Soho brothel where the clients included titled gentry. ‘This is hard to believe, because I thought that in 1890 we were invisible, that our invisibility was a fact,’ says Bartlett.[3] But Whibley ‘must have been sure that his readers remembered the headlines of four years earlier’. The very title of Bartlett’s book, Who Was That Man?, plays on the unintelligibility of the newly formed homosexual, which was yet to be successfully confined to the effeminate model — that would happen in the wake of the demonisation of Wilde in the years that followed his trial.

When the Marquess of Queensbury left his accusatory card for Oscar Wilde which precipitated the events that lead to the writer’s imprisonment, he signed it, ‘To Oscar Wilde, posing as a somdomite’. This misspelling is usually explained as a mistake provoked by Queensbury’s anger or ignorance. But did he in fact want to disavow his acquaintance with the word? The porter of the Albemarle club with whom the card was left ‘looked at the card, but did not understand the meaning of the words’.[4] Indeed the phrase was recorded as ‘Posing as a *****.’

Perhaps, then, it is in some people’s interests to overlook the idea that skinheads might be gay, even when their homosexuality is presented unambiguously.

A shared mythology

Even within the fairly reductive definitions of ‘gay man’ and ‘skinhead’ in circulation in the mainstream, what both categories have in common is some interest and investment in the notion of an ‘authentic’ working-class masculinity. That requires a further qualification: the skinhead represents a mythology of specifically white, working-class masculinity. Which is of course not to say that everyone who has ever been a skinhead is white (or indeed working class, or male). Nor is it to suggest that all gay skinheads and their admirers are inherently, or subconsciously, racist. But the skinhead is a significantly racialised figure — more so than is the case with other working-class youth subcultures (such as Teds, even though in their day they appear to have been predominantly white and associated with racist violence) — largely, I suspect, because of the way far-right groups sought to adopt the image of the skinhead in the early 1980s, and continue to do so today in mainland Europe.

The existence of gay skins demands that we reconceptualise not only homosexuality but skinheads too — the way gay subculture has fetishised, utilised, rejected and appropriated the supposedly ‘natural’ masculinity embodied in the skinhead. My suspicion is that skinheads hold an erotic fascination for gay male subculture precisely because they represent and preserve all these conservative notions of masculinity; this may of course lead to some troubling, unwelcome conclusions.

Of course, the circulation of conservative masculine signifiers within gay subculture may actually serve to undermine the status of such a naturalised definition of masculinity. Certainly the gay skinhead holds a powerful potential to refute straight expectations about gay men (which, even today, site them as the descendants of a line of queens from Oscar Wilde via Quentin Crisp), and may problematise heterosexual masculinity’s claim to authentic status in the process.

What I hope I’ve just shown is that the terms ‘gay man’ and ‘skinhead’ share a contradefinitional dynamic. Between them they preserve a naturalised masculinity, which in turn precludes anyone from adopting both identities (and, as we saw in the case of Wolf, dematerialises anyone who dares to try). What I hope to find out in the course of Gay Skins is whether the gay skinheads who nevertheless managed to exist from the late 1960s onwards, and whose stories I have collected here, managed to short this closed circuit of masculinity.

2. Kids, Cults and Common Queers

English may not have a grammatical gender, but the common usage of phrases such as ‘male model’, ‘female doctor’, ‘male nurse’ and ‘lady driver’ shows that many nouns are implicitly gendered. The fact that gendering extends beyond sex to sexuality, and that, even today, the phrase ‘gay skinhead’ exists is symptomatic of the assumption that skinheads by definition must be straight.

The official skinhead histories — sociological papers trying to understand the phenomenon, the cultural activity of those participating in it, and press reports condemning it — are not very useful if you’re looking for gay skinheads. Not only were none of those authors looking for them; by definition, such a thing could not even exist. As for the gay skinheads who were enjoying themselves in the late 1960s despite their supposed non-existence, they weren’t going out of their way to draw attention to themselves.

To understand how and why the categories ‘gay man’ and ‘skinhead’ define against each other, it is necessary to examine the other binarisms implicit in this opposition: working class/middle class, masculine/effeminate, natural/unnatural, heterosexual/homosexual. These oppositions are arranged to generate the ‘truth’ that skinheads are working-class, violently aggressive, inarticulate, politically right-wing real men. Gay men, on the other hand, are middle-class, passive, creative, politically left-wing failed or false men. Yes, these are stereotypes; obviously there are articulate skinheads, gay Tories, antiracist skinheads, macho queens, gay skinheads and so on. But these are the expected, generalised qualities used to define social groups; it is through the creation and regulation of stereotypes that the dominant culture polices its subjects. I want to show how a particular notion of masculinity is made to seem natural, and how certain groups are excluded from this ‘natural’ masculinity, by highlighting the disruptive possibilities that these oppositions are supposed to preclude — the gay skinhead being a prime example.

According to this grid of assumptions, class divisions exclude gay men from skinhead subculture. The skinhead is a workingclass youth cult from the late 1960s whereas gay or homosexual identities were supposedly available only to the middle classes until the late 19 70s. In short, skinheads are expected to be rough and queens are expected to be a bit posh.

Common queers: who are you calling gay?

Axiomatic to lesbian and gay studies is the view that until the aftermath of the Gay Liberation Front, gay was a middleclass identity. As Joseph Bristow has observed, ‘It is impossible to come out as politically gay if there is not to begin with any culture in which we can identify ourselves.’[5] The argument runs that working-class men had no access to such a culture; their restricted social mobility in this period supposedly restricted them from the bourgeois realm of homosexual subcultures. Bemoaning the dearth of evidence with regard to working-class homosexuality, Jeffrey Weeks writes, ‘We may hypothesise that the spread of a homosexual consciousness was much less strong among working-class men than middle-class — for obvious family and social factors.’[6] This lack of material is presented then as proof of the non-existence of working-class homosexual subcultures.

The arguments that, until the 1970s, only middle-class men could identify as gay, can seem fairly convincing: the effete, posh Oscar Wilde, middle-class with aristocratic aspirations, has dominated homosexual identity in the twentieth century, making the homosexual identity which emerged in his wake particularly pertinent for other middle-class men; homosexual rights groups campaigning for political change and law reforms have been dominated by middle-class, university-educated homosexuals; professions which tolerated homosexuals — the theatre, the fine arts, fashion — were middle-class. Most of the inadequate existing material on homosexual identity in the first half of the twentieth century reveals that male homosexual identities only existed either as a part of the broader leisure industries for middle- and upper-class men by way of networks established through underground clubs in cities, or, to a lesser extent, as a political or intellectual identity within the cultural or academic elite. Both were extensions of upper-middle-class culture and carried its values, and both were inaccessible to most working-class men.

Also, the adoption of a homosexual identity for working-class men may have been precluded by material conditions. Changes in British society after the Second World War led to what has been referred to as a ‘privatisation’ of sexuality. The Wolfenden Report, commissioned by the British government to advise on law reform in the area of sexual conduct, was published in 19 5 7, declaring that the state should not ‘intervene in the private lives of citizens’[7] but instead concentrate on ‘the public realm’. It was radical in so far as it effected legal and political changes which put ‘private’ activity, including sex between men over the age of twenty-one, beyond the reach of the law. But this move privileged those who could afford private space — that is, the property-owning middle classes. As if to compensate for this liberalisation, the law reasserted its moral function by redoubling its efforts within its newly restricted domain of public space, and there was a sharp rise in the number of men arrested for cottaging in the years following the partial décriminalisation of male homosexuality. As such, men who could not move within the limited areas of society that tolerated homosexuals found their efforts to find sex with other men more hazardous.

Cultural analysis informed by Marxist criticism has identified these moves to create a ‘privatised’ sexuality in the post-war period as inherently bourgeois, dependent on notions of private property and the individual: ‘The structure of the middleclass environment... is based on the concept of property and private ownership, on individual differences of status, wealth and so on, whereas the structure of the working-class environment is based on the concept of community or collective identity, common lack of ownership, wealth, and so on.’[8] Illustrating how property ownership benefited middle-class homosexuals is the testament of Janine, a lesbian in 1960s’ Brighton:

If you were extremely middle-class and gay and you’d sorted yourself out and you had inherited money and you owned your own house, then you made a circle of friends and it was an extremely selfish life. You didn’t think as much as I do now that you needed to support gay causes, I mean they were things, on the whole, that happened to other people.[9]

The ‘privatization of sexuality’ made the adoption of homosexual identity by working-class people, and the formation of a collective identity, more difficult.

So homosexual identities were not available to working-class men until fairly recently: they got married, had children and generally conformed to dominant notions of masculinity. If they did engage in same-sex activity, it was discreet and did not involve questions or problems of identity.

Or so the argument runs. But try putting it to working-class men who were gay in the 1950s and 1960s, as I have in the course of writing this book, and the response you are likely to get is concise, unambivalent and in the negative. Their own biographies render the widely accepted general-ization that ‘gay’ is a middle-class identity a nonsense. Even if one accepts that access to homosexual subcultures was restricted for working-class men, the adoption of an identity is not solely dependent on access to a subculture. Few children grow up with access to gay subculture or to lesbians and gay men. Most people identify as gay, in their early teens, in isolation, before they have access to a scene or meet other homosexuals; indeed, it is this primary identification which motivates the subsequent formation of those links.

Knowledge of homosexual identity is what is required, and certainly post-war working-class epistemology did not fail to include deviants. Partly as a backlash against moves towards legislative change in favour of homosexuals, sensationalist stories about queers slowly started to appear in working-class newspapers at this time. In 1952, the Sunday Pictorial ran a series of articles called ‘Evil Men’. It was about ‘pansies — mincing, effeminate young men who call themselves queers. But simple decent folk regard them as freaks and rarities.’[10] Censorship and taste meant that the issue could rarely be dealt with directly; disapproval had to be expressed, but in a way that did not educate those not already aware of it. However, according to the Sunday Pictorial feature, by 1952, ‘Most people know there are such things’, heralding a project of marginalising and stigmatising queers — which nevertheless provided a point of identification for men with deviant desires reading these reports.

This series of articles marked the end of what the paper’s former editor, Hugh Cudlipp, tellingly referred to as a ‘conspiracy of silence’ about the ‘spreading fungus’ of homosexuality.[11] Everyone knew about it, but nobody dared write about it. And a similarly conspicuous and loaded silence characterises our (lack of) knowledge about homosexual identities in this period.

One problem lies in defining the parameters of ‘gay’. The word was taken up by gay rights campaigners in the late 1960s to counteract the pejorative connotations of the alternative labels: its use formed part of a political project to build a positive sense of collective identity. These movements were dominated by middle-class, university-educated men; so if ‘gay’ refers specifically to such politicised subjects, then this does reduce the likelihood of working-class involvement. However, in actual practice the word ‘gay’ was used to refer to sexual (self-)identifications well beyond these narrow limits. The word’s homosexual appropriation derived from the nineteenth-century use of the word as a slang reference to prostitution. And although its revival by rights movements to some extent divided those people identifying as homosexual along generational grounds (some older homosexuals objected to the use of ‘gay’ on the grounds that it ‘tainted’ an ‘innocent’ word), it was taken up, even at the time, by people who had no direct involvement with those movements. In the late 1980s, the postmodern critique of lesbian and gay identity politics, which later became known as ‘queer’, alerted some lesbian and gay academics and activists to the historicist specificity of the word ‘gay’ and the folly of applying contemporary understandings to other periods of history. This too would seem to limit the definition. But I would question the motivation in such exercises of delimitation: even in the wake of queer, labelling is perceived to be a matter of aesthetics rather than historicist semantics for most lesbians and gay men. A feature in the gay listings magazine Boyz which asked gay men at the Men’s Ponds on Hampstead Heath how they liked to be termed evinced responses such as, ‘I hate the words nancy and pansy — they sound so waspish and antiquated’, ‘I do like the sound of the word wussie’, ‘I don’t like the word fag, it sounds American’, ‘I went off nancy because of Nancy Reagan’, ‘I hate the word homosexual — it sounds so medical’.[12] Given that queer set out to shake up the liberal lexicon of polite, acceptable, ‘politically correct’, terms, it is interesting that for one respondent the Q-word was a neologism he felt obliged to adopt: ‘I suppose if I’m being really PC I should say I don’t mind being called queer, though I’m still not used to that yet.’ The most popular word by far was ‘gay’.

But when considering and constructing ‘gay history’, the constituency denoted by ‘gay’ reverts to a more restricted definition, that of politically informed, middle-class homosexual men. Much sociological work on post-war homosexual identity has focused on this narrow definition of ‘gay’, and those who do not conspicuously conform to it are simply not going to register. And true, it was unlikely that you would come across many kids wearing GLF badges on council estates in the early 1970s. So working-class involvement is precluded literally by definition. Consider the tautology here: working-class men had no access to gay identity. Why? Because ‘gay’ is a middle-class identity. Why? Because working-class men had no access to gay identity... Whose interests does this exclusion serve?

Perhaps we should not be too surprised. The fact is that until fairly recently, most of the work being carried out on homosexual identity was within academia, itself a middle-class environment populated by a majority of people from middleclass backgrounds perhaps not best suited to understanding working-class cultures.

But it may be more than misunderstanding at play here; this lack of knowledge may be motivated by a desire to preserve certain fantasies about class — specifically, to leave undisturbed unspoken assumptions about the ‘natural’ straightness of workingclass men. There is much effort in sociological analyses to preserve the working classes as homo-free. For example, the rent boy, modern history’s one instance of a conspicuously visible working-class homo, is usually presented as a solution to a problem of economics, not sexuality: ‘There is a subculture involving young boys in the gay world, known as “chickens”. They can be heterosexual boys, using a market-place for prostitution.’[13] In The Naked Civil Servant, however, Quentin Crisp describes his involvement in a street culture of the 1950s, where working-class youths take to prostitution not so much for the money as for the access it provides to a homosexual identity and sex. We need to ask ourselves why the belief that rent boys are really straight is so persistent, even today. Could it be that working-class men embody a more authentic masculinity for many middle-class men, and the need to preserve that authentic masculinity as unqueerably straight has predisposed the analyses to the exclusion of working-class men? Middle-class gay men who have invested in fantasies about sex with ‘real’ men (as the posh queens themselves phrased it, ‘rough trade’) would have all the greater investment in maintaining this belief. Working-class lads have to be kept straight.

Or there may be a political explanation: one could go so far as to speculate that those gay academics themselves researching in this field may have had some investment in restricting and preserving gay as a political identity, leaving them little incentive to research into homosexual identities which did not contribute to obviously progressive or radical politics.

Queer, in debt to Foucault, popularised the notion that there are many ‘(homo)sexualities’, that the territory of sexual dissidence is ever-changing, and that we need to look beyond ‘homosexuality’ as it is positioned within today’s cultural organisation of sexuality, as the very concept of sexuality itself is a recent phenomenon. Certainly queer is a very useful tool with which to organise discoveries of sexual identities which do not fit the authorised categories of hetero/homosexual. But my suspicion is that there were many working-class men articulating an identity recognisable as being somewhere in the orbit of ‘gay’ (by today’s understandings of the word) in the post-war period.

I am not suggesting a conspiracy theory here, a conscious cover-up: I am questioning motivation rather than making accusations of deliberate exclusion. Given that categories create constituencies, lam not unsympathetic to the theory that ‘gay’ was a product of, and therefore made more sense to, liberal bourgeois discourses of the individual, identity, family and society. But although their material conditions differed from those of the middle classes, working-class people may have shared with them an imaginary relation to society, one mediated and maintained by culture; indeed, consensus politics would require any material differences to be negated by a shared imaginary relation — through culture, say, or religion — lest the perception of those differences provoke social unrest. Whose imaginary relation this was is hard to say, although obviously bourgeois ideology could assert itself all the more successfully in the changing lives of working-class people through various cultural sites (new housing, consumerism, TV scheduling). So even if ‘gay’ was a middle-class identity, to assume its availability was restricted to that class is surely naive. And to take this as read in the absence of any material to the contrary, and then to cite that absence as a reason not to bother discovering it, is suspect to say the least. That we know so little of pre-‘liberation’ workingclass homosexual identities is perhaps due not so much to an absence of such participants as the class identity of those doing the analysis.

Working-class homosexuals

In fact, what recent, more grass-roots-orientatedwork in recovering gay history shows is that working-class men and women both felt the need to, and in many cases could, articulate a homosexual identity. For example, the Ourstory Project’s book Daring Hearts and the documentary Storm in a Teacup (commissioned for Channel 4’s 1992 series of Out) show that in the south of England in the 1950s, pubs existed which catered for a more or less exclusively working-class gay clientele. Daring Hearts records the memories of lesbians and gay men in the Brighton of the 1950s and 1960s, where the scene was strictly structured on class lines because, as one participant recalls, ‘there were queers among the upper, the middle and the lower classes, but in those days a lot of queers were inclined to be a bit snobbish, they mixed with their own set’.[14] So the scene was complex enough to accommodate gay men of various social backgrounds; the Regency Club, for example, ‘was very much a working-class club’ defining itself in opposition to other more ‘gentlemanly’ venues. These men then identified themselves as gay within a workingclass culture. The working-class homosexual community remembered in Storm in a Teacup was based around the dock pubs of East London. Here the subculture was well established enough to have its own language, polari, a mutation of nineteenthcentury East End traders’ slang influenced by the language of local immigrant communities.

As Daffyd Jenkins, the manager of a gay club in a working-class area of south-east London, points out, the very history of the gay scene in Britain tends to contest the assumption that ‘gay’ is a middle-class identity:

Most of the established gay pubs have grown up in rough working-class areas. The East End, for all its macho-ness, the people there are far more accepting of everything. The London Apprentice is in the middle of an extremely rough area, but they don’t have bother. The Union Tavern was in a very rough area. The White Swan, too. Wherever you go — Swansea, Cardiff, Birmingham, Manchester — OK, the places nowadays tend to be in the city centres. But most of the gay scenes in cities started in the working-class areas. Plus a lot of the gangs that ruled, that even rule now, in the East End, have faggot connections. The Krays, the Richardsons — lots of them had gay connections. It’s not a problem. The average working-class man or woman has far more to worry about than who’s screwing who. They really don’t care.

His own experience as the manager of the Anvil contradicts the notion that working-class men are more hostile to homosexuality:

The police didn’t want us to open here, because it’s a very, rough, gang-ruled area. They said we’d be inviting trouble, but we’ve had absolutely no trouble. In fact, when the people across the road started objecting to our licence, it was the local people from the council estates at the back who wanted to start a petition in our favour.

He claims there was no difficulty in him identifying as homosexual growing up as a working-class man in the 1960s: ‘My father was a miner, my mum was a cleaner; just because I now own a business, I don’t consider myself any less working-class, as the Gay Tory Group found when they came round for a subscription the other week.’ As a gay working-class teenager he had no access to a local commercial gay scene; it was not until his twenty-first birthday that he visited his first gay venue, after finding a copy of Gay News on the train. But there was a social and sexual network where he lived which centred on public toilets:

When I was about thirteen, the headmaster gave us a talk about this cottage, telling us about how it was disgusting, how there were evil-people there, how we mustn’t go anywhere near there. So I thought, oh good, and I made a note of the address... I had a wild time. Out in Surrey, in Caterham, where I lived then, cottaging wasn’t a sexual thing. You used to go to the local cottage to meet your mates. It was the local nightlife.

Cottaging is generally not considered within the survey of ‘pre-liberation’ working-class gay identities because it does not necessarily require any recourse to a queer model for those involved; it is judged to be activity- rather than identity-based. Daffyd’s recollection here however suggests it was the basis of a social scene with regular participants who identified as homosexual. Other testaments from this period would support the ‘activity, not identity’ thesis, however. Dennis recalls in Daring Hearts that before the advent of the contraceptive pill, cottages were much more popular for men wanting nonprocreative sex: ‘They weren’t gay, these people, they were just randy and wanted serving.’[15] Daffyd himself concurs that not all participants were queer. He recalls one particular cottaging episode: T walked in there and there was this massive great skinhead. I had a wild time.’ He concedes that ‘He was straight; one fuck does not a faggot make.’ But his experience of cottaging was that it provided a focus for working-class men who not only identified as gay but did so vociferously. ‘If you were gay you had to be a screaming Mary, there was no two ways about it, you couldn’t be gay and macho. If you weren’t a screaming Mary, you weren’t a proper queen. The few that were around that were not overtly faggot were oddities in a way.’ We know that Wilde’s legacy, the effeminate stereotype, had become available as a model of homosexual identity to lower-class men by the 1950s. This model has not been forgotten by history, and cannot easily be silenced, precisely because it is so self-proclaiming and defiantly visible. Indeed, it readily leant itself to demonisation by the normalising processes of mainstream culture.

Many working-class men who desired same-sex sexual activity found that it did involve questions of identity, and damning press coverage, such as the ‘Evil Men’ article in the Sunday Pictorial, at least made it known that other such people existed. Access to a scene where they could meet others like themselves might have been restricted, but there was at least the potential for identifying with this model (it was real — it was in the newspaper), however difficult.

But for those men who did not accept that their homosexuality was at odds with the conventions of masculinity, the ‘screaming Mary’ option was not a satisfactory solution. One such gay man of the 1960s told me:

Looking back to the sixties, we’re talking of a time in which, when I was 15 in 1961, homosexuality was illegal; there was the whole threat of being thrown into prison. So there was no thought of being upfront gay in the street — apart from the Quentin Crisps of the world. But I couldn’t be like that. That sounds like a criticism, but it isn’t, I just wouldn’t dare do what he did — I don’t like being called names like that, for a start.

His lack of access to a commercial gay scene compounded the problems he faced around his identity:

I lived in a small working-class town, I didn’t know where gay men met, there were no gay publications, you had virtually no chance of finding a gay bar; the society was secret. So being young and gay was almost hopeless. No wonder people from that time became neurotic; you just felt helpless.

The alternative for those who had no access to the commercial scene, cottaging, proved equally fruitless:

I knew people my age at that time were getting jerked off in men’s toilets, but I hadn’t been. In fact, every attempt I made to try to be where I thought gay people might be, they weren’t. It was just appallingly difficult. So I ended up getting to 21 and I hadn’t had sex, I didn’t know what a gay bar was, not really accepting I was gay, not expressing anything, totally neurotic about sex. I didn’t know anything.

And yet this young working-class man could still identify as gay. Where he found solace was in youth subculture: first as a mod, then as a skinhead.

The Leather Boys

In 1963 The Leather Boys was published.[16] On the face of it, it appeared to be a teen schlock novel about the aggressive, violent, destructive, demonised youth culture of the day: leather-clad bikers. John Gross in the New Statesman dismissed it as a ‘potboiler about motor-bike gangs bashing one another to death’.[17] Significantly, Gross and his fellow reviewers failed to mention the romantic sexual relationship shared by the book’s two heroes, Reggie and Dick; it’s hard to know whether they found this aspect of the book unremarkable or simply hadn’t bothered reading it. This oversight was redressed twenty-four years later when the book was reissued by Gay Men’s Press in its Gay Modern Classics series, earning a review in Gay Times magazine (in its section devoted to leather culture, in fact).[18] Written by the journalist Gillian Freeman, The Leather Boys is perhaps best considered a ‘social problem’ novel about working-class identity, and, in particular, the difficulties experienced by working-class boys in identifying as gay. The fact that she should be able to site what amounts to a queer romance so easily within the most aggressively masculine environment of the day without it appearing nonsensically contradictory is significant. (Interestingly, Freeman originally wrote the novel under the name of Eliot George, inverting gender and queering literature in one fell swoop.) Given the supposed absence of working-class homosexual identities of this period, this seems conspicuous, and raises questions about the possibilities that teen culture allowed working-class men to articulate some idea of a homosexual identity.

Men having sex with men did not necessarily make them queer, and the existence of same-sex sexual activity which did not problematise sexual identity is acknowledged in The Leather Boys: some of Reggie’s biker friends openly have sex with ‘leather johnnies’ to make money, and Dick acknowledges that ‘men did do things with other men when they felt randy, everyone knew that. It didn’t mean they felt anything special, though.’ Similarly, Reggie thinks about how ‘blokes often had sex together if there were no girls around, in the army and things’.

But their knowledge of this circumstantial model of all-male sex only serves to illustrate how it does not apply to either of them: they experience homosexual desire specifically, emotionally and individually as part of their identity. Reggie considers sex with Dick as ‘deliberate and what he wanted’, and although he cannot identify as queer, he cannot dismiss the possibility either: ‘he thought, why should I feel like this over Dick, I’m not queer. But perhaps he was, if he felt as he did’ (p 70).

The young bikers do find access to gay subculture but feel alienated by it. Straying into a gay pub, Dick is chatted up by a man ‘in jeans and an open-necked shirt, his fingers covered with cheap rings... Dick could see powder on his face and a metal bracelet on his wrist. His open neck revealed a silver cross on a chain... nestled among the greying hairs on his chest. In contrast his hair was brilliantly blond’ (p 101). But Dick cannot identify with such a model:

He had never seen homosexuals like them before. He had never thought of his relationship with Reggie as being homosexual, he hadn’t labelled it or questioned it. It wasn’t like this. They would never be like these men. (p 162)

After declaring his love for Reg, Dick says, ‘It’s funny, isn’t it. I mean, we don’t want to put on lipstick or anything like that, do we?’ (p 71). He cannot identify with this camp homosexual identity (although ‘He had never seen homosexuals like them before’ does suggest other models were available: the ‘leather johnnies’?). He does, however, feel an urge towards a romantic declaration that we might recognise as coming out: ‘there had been times when he had wanted to blurt out, cry out, we loved each other. But he couldn’t. There was no one, no one, no one he could tell’ (p 126). But to come out as what and into what?