Steve Platt

Light in dark places

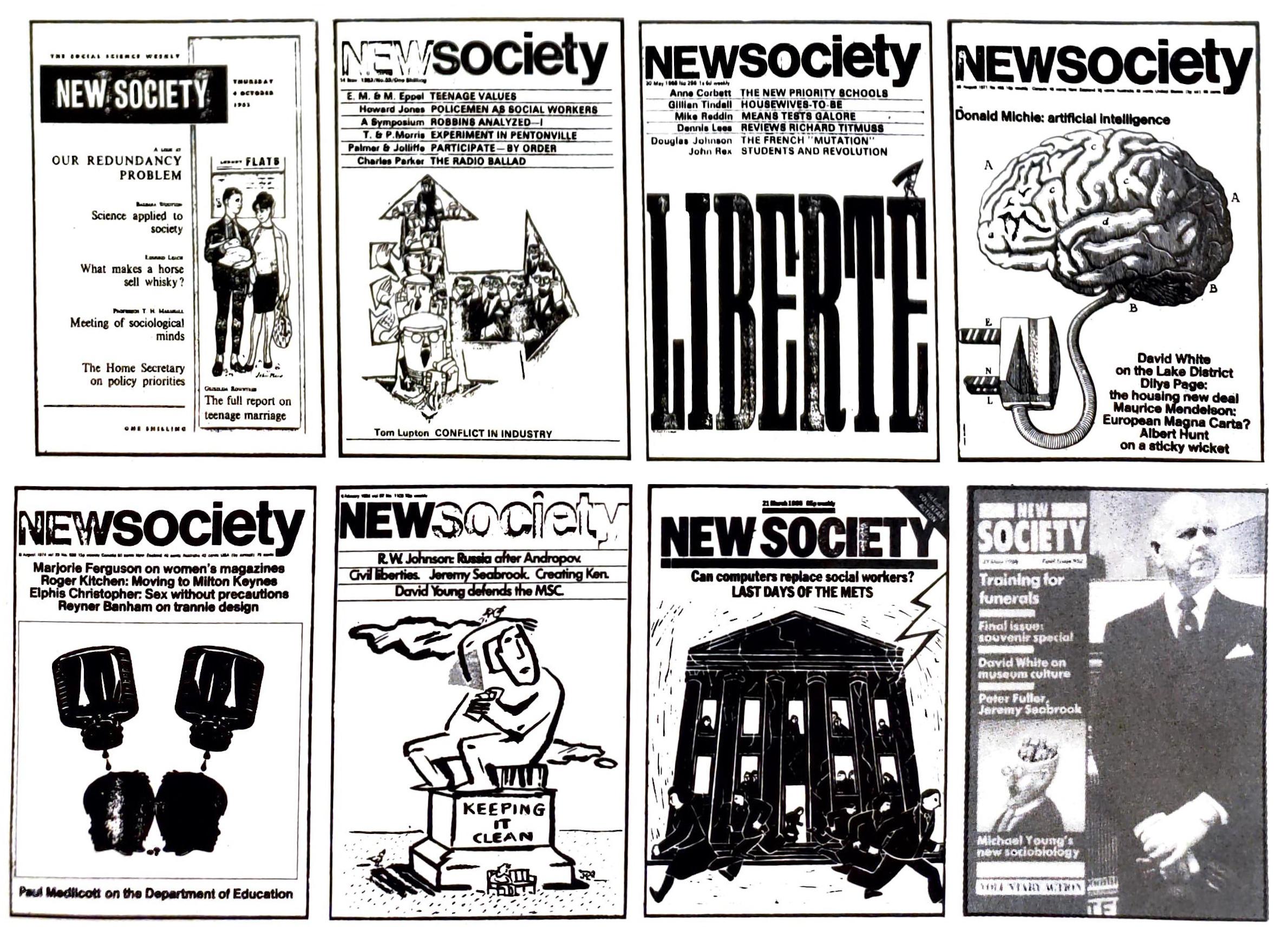

Macmillan had just sacked half his cabinet and the Beatles had just played Love Me Do when the first issue of ‘New Society’ appeared. Here its final editor traces the life and times of a magazine.

Twenty years ago, almost to the day, the first issue of a new magazine hit the streets. Black Dwarf, an anarcho-Trotskyitc fortnightly claiming continuity with an early 19th century predecessor of the same name (“Established 1817. Volume 13, Number 1,” proclaimed the 1968 version’s masthead), was both to report and symbolise the new radical politics of that turbulent time.

NEW SOCIETY, then five years young and at the beginning of Paul Barker’s epic 18-year tutelage as editor, was also reporting on the events that have since passed into folklore (and Channel 4 documentaries). From Columbia to Prague, from Hornsey to Belgrade, the magazine noted on 20 June 1968, the world—or at least that part of it populated by students bom in the postwar baby boom—was in turmoil. “Much of the time, in most of these places, the students have been blatantly right,” opined Paul Barker’s leader in the 20 June issue. “Students are studying how to think—or, at least, that’s the idea. It’s no good complaining when that is precisely what they decide to do.”

Thinking—studying and analysing society, often in unexpected or unpredictable ways—was what new society was all about. Paul Barker may have considered that the students of ’68 were “blatantly right,” but that certainly wasn’t the end of the story. While others of that era became lost in revolutionary romanticism (a subject to which new society later devoted a special series), his magazine provided a wider, more considered, and balanced, analysis.

Thus, for example, Diana Spearman, for twelve years a worker in the Conservative Party’s research department, was twice given space to analyse the 110,000 letters received by Enoch Powell following his “rivers of blood” speech about immigration in April 1968. All but 2,030 of the letters approved of what Powell had to say—as clear an indication of the true spirit of ’68 as anything which Black Dwarf was to go on to publish.

Thus too, at the height of the ’68 radical fever, a young Dennis Potter was encouraged to write about the “armchair revolution” that underlay the launch of Black Dwarf. Noting the front page slogan of Black Dwarfs first issue—“we shall fight, we--WILL WIN, PARIS, LONDON, ROME, BERLIN”--Potter commented: “If the list had been compiled out of, say, Oldham and Cardiff and Rochdale and Glasgow, the contents might have had more scalpel-like relevance and the muscularity of a more genuine urgency.” But no, he continued: “The familiar, tired old phrases pile up like cobblestones, except that you cannot even throw them.” Black Dwarf, said Potter contemptuously, was “full of totally humourless attacks on prosperous respectable men by other prosperous if determinedly unrespectable men.”

I wasn’t old enough to read Potter’s demolition job on some of the myths of ’68 at the time. But discovering it 20 years later, when the 1968 retrospectives are flying thick and fast, it seems as perceptive and prescient a piece of writing as is ever likely to have come out of that period. It epitomises what, for me, was new society at its best: a magazine which encouraged good writers to say what they wanted, free from pressures to conform to some predetermined political or editorial line, and which could cast new—at the time often heretical lights on important issues.

NEW SOCIETY was never afraid of upsetting its own constituency—or even its own writers—in pursuit of this end. Recently, for instance, by printing Peter Fuller’s assault on John Berger—and then John Berger’s reply, Mike Dibb’s riposte and finally Peter Fuller s return to the discussion in this issue—the magazine has managed to infuriate almost every section of the old “Arts in Society” loyalists, as well as each of the principals in the unfolding debate. On other subjects, Geoffrey “Tailgunner” Parkinson and, in her day, Julie Burchill, have been permitted to offend significant minorities among the readership—leading to a boycott of new society and its journalists by some black probation officers in the former case, and to a threatened picket of the new society offices outraged gays in the latter.

Less recently, in 1975, a now long-forgotten article by Enoch Powell (on nationalisation) prompted a row’ and threatened walkout by some of the magazine’s leading contributors. And, in 1971, the publication of an article on race and intelligence by Hans Eysenck led to a staff rebellion and a letter to The Times in which the magazine’s journalists dissociated themselves from the editor’s decision to publish.

Controversy also crept into the books pages. E.P. Thompson’s assault on Claire Tomalin’s The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft in 1974 divided readers and reviewers alike into two opposing camps. Angela Carter’s withering review of The Women’s Room by Marilyn French (“Room with a loo,” 20 April 1978) offended many feminist friends. (“This novel is of no literary merit, combining windy rhetoric ... with the thumping mundane,” Carter wrote. “Feminism minus class analysis equals cul de sac. Which is what we have here.”) And, in 1977, Ruth Glass did the whole of urban sociology a favour at a time when the French obscurantist Manuel Castells was still highly regarded by dismissing his book The Urban Question: a marxist approach as “cryptic, hideous verbiage ... a slovenly, fatty, pretentious concoction.”

In the context of these examples, it is difficult to accede to David Widgery’s assertion, in a 20th anniversary issue review of the new society anthology The Other Britain, that it was “telling that the only polemical piece of writing is directed against vegetarians, not exactly the main enemy.” Widgery complained that the “very sophistication” of new society’s observations “elides with a kind of political quietism where all ideologies are suspect, all larger passions fanatical and an ironic self-interest the most honourable (or at least most honest) political stance.” Of the new society tradition of social reportage, he wrote: “At its worst, the genre degenerates into a procession of closely observed nuances unencumbered by analysis or argument, an unfortunate cross between a college lecturer’s version of ’What I did on my holidays’ and the voyeuristic vision of the uk as a kind of sociological theme park.”

Paul Barker, who described new society’s social reportage idiom as “rational, humane, unsectarian, unsnobbish,” would have regarded the absence of polemic as a strength, not a weakness. What David Widgery called “uncommitted,” he would have said was objective or impartial. But the magazine’s reputation as a fence-sitter invited persistent criticism. David Lipsey, a former staff writer who took over the editorship from Paul Barker in 1986, tells of once writing three editorials in a row which ended with the conclusion: “Time alone will tell.” The tale sounds improbable, but that sense of a magazine without an editorial line was strong—and deliberately and proudly cultivated.

Writing in the tenth anniversary issue, in October 1972, Paul Barker put it like this: “new society has never given general support to any party; never tried to tell its readers how to vote. (A pointless exercise in any case: rather like trying to tell the Chancellor of the Exchequer, on budget eve, what to put in his budget.) No one, of course, can be totally objective. But one can try to find out what facts there are, and form as honest a conclusion as one can.”

Unashamedly rationalist, the magazine was established in the confident belief that the study of the social sciences would contribute greatly to the improvement of the human condition. “We believe that an enormous amount can be achieved through the honest search for facts and the disinterested application of the conclusions that the facts support; and that this can be just as much the aim of the journalist as it is of the social scientist,” said the editorial statement in the first issue. Ideas and theories were to be important, but: “We aim above all to link the study of society with practice ... The experience of the practitioner and the research of the academic are complementary, and our contributors will be drawn from both groups.”

This was an optimistic period for the social sciences—“those expansive times when people who’d only popped onto campus to fix the central heating ended up as Readers,” as Laurie Taylor was to put it in a new society article 20 years later. The first issue’s editorial statement confidently called for the creation of a “Human Sciences Research Council, comparable with the Medical Research Council and the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research,” to inform and influence social policy. Three years later, in 1965, when the Social Science Research Council was set up, its first chairman was Michael Young—the co-author of the then recently published Family and Kinship in East London, and the man who, over lunch with Timothy Raison, had first suggested the idea of new society.

Raison, now a Tory mp, was new society’s first editor. Formerly a staff writer on Picture Post where his father. Maxwell Raison, was the managing director—he left with his father in 1956 to set up New Scientist. The magazine was an immediate success, subsidising new society through its early lossmaking years, and then being sold, along with new society, to the International Publishing Corporation in 1966. new society went on to achieve a peak circulation of around 40,000 in the mid-seventies, at which time it regularly ran two dozen or more pages of classified advertising—a commercial success story which persuaded ipc and its rivals to set up the specialist publications which eventually undermined new society’s own advertising base.

The late sixties through to the mid-seventies were new society’s heyday, culminating in the famous affair of the leaked Cabinet minutes in June 1976. The publication of extracts from these minutes, which detailed the way in which the Labour government had decided indefinitely to postpone the introduction of the new child benefit scheme, splashed the name of new society across every newspaper in the land, led to a top level inquiry into how the leak had occurred, and ultimately forced the government to back down and introduce child benefits immediately after all.

Exciting though it was at the time—one former staff writer fondly recalls the frantic lavatory flushing and smell of burning paper in the ladies’ loos as potentially incriminating evidence about the source of the leak was burnt—this was not typical new society journalism. Nor is it the sort of thing for which new society will most be missed: there are other outlets for such journalistic scoops.

What will go with new society—and what New Statesman and Society can never wholly replace—is a unique interface between the practical, academic and journalistic worlds: between, in a sense, those who do, those who think about doing and those who write about it; between the worlds of action, ideas and reportage (including photography and illustration, for which new society has always provided an effective and innovative home). This is one reason why so many of new society’s best writers were not, first and foremost, journalists—and why so many staff writers who went on to make reputations for themselves as journalists were drawn not from other magazines or newspapers but from the world of I social affairs.

There cannot be many magazines that would have found a home for both Arthur Scargill (on the case for conflict) and Bernard Ingham (on energy saving); for Cedric Price and Colin Ward; for Ivan Illich and Angus Maude; for Peter Jenkins and Clive Jenkins. Nor which turned down Neil Kinnock (for being too brief) and Roy Hattersley (for missing his deadline).

At times the magazine’s commissioning strategy could degenerate into sheer quirkiness; and some of the pieces which it published, particularly in the early years, now seem simply bizarre. As Martyn Harris noted, in the 21st anniversary issue of 6 October 1983, the trouble with a retrospective exercise is that “it inevitably becomes a luxurious wallow in hindsight: a sort of orgy of superiority over the past.” Even so, we should be permitted, if not a wallow, at least a brief soak.

What are we to make, for instance, of the 1962 article by Colin Maclnnes—in the old “Out of the Way” slot—which he devotes entirely to an attack on telephones? “How is it possible we have put up for so long with an instrument that is inconceivably ugly, impractical and unhygienic?” he asks. Or how, in 1988, does one assess the piece “Beat and Gangs on Merseyside,” by Colin Fletcher--“an undergraduate reading sociology at Liverpool”--which was published in February 1964? “A first-hand history of two gangs tells how beat music invaded the adolescent gangs of LIverpool and changed them,” says the introduction. A kind of sociological West Side Story, the article tells how the author was a member of two “teenage” gangs--until, at the age of 16, he became the singer and bass-guitarist of a “rock group” (the self-conscious inverted commas were a feature of all such articles in the early years) and gave up street-fighting for a place on a sociology degree course.

Go boldly and courteously

There are, of course, the howlers that no one could have foreseen at the time. “The IRA seems to be a thing of the past,” says the editorial of 12 December 1968. And there are other nuances that we can now feel superior about too, particularly around issues of race and sex. To pick on Colin MacInnes again--he was such a good writer that his reputation can stand it--who would now write: “To meet coloured people for whatever motive can be so delightful an experience if the attitude be right ... All you need to do is go boldly and courteously up to one and say you’d like to make his or her acquaintance” (“How not to get thmped,” 27 June 1963.

In fact, NEW SOCIETY Was probably more forward looking, particularly on the subject of race, than most other publications (who today would call a magazine Black Dwarf?). Its most insensitive racial gaffe-a cover story entitled “How Young Asians See Us”-appeared in 1985. Yet for most of its history--from a November 1962 piece by Ray Gosling on young white racists to the recent publication of the monthly R ace in Society” supplement-it has been far more aware of the full range of ethnic groups that go to make up British society, and of the issues that concern them, than almost any other publication.

The decision to close NEW SOCIETY was taken hurriedly on flimsy financial evidence at the begin ning of February this year. Both of the current shareholders-the Joseph Rowntree Social Services Trust and the New Statesman Publishing Company--had already put considerable sums of money into the magazine since it was sold by IPC in 1984; they were a afraid that its continued publication would constitute a further drain on their limited resources.

In fact, after a slight dip in advertising revenue last autumn, the magazine has been trading at a small small profit; its circulation has continued to rise, and all prognoses were good. Outside buyers had expressed an interest in taking a shareholding; a staff buyout was another possibility.

Yet none of the alternatives to merger with the New Statesman were investigated. The decision to merge the two magazines was reached in secret without consultation. Only the two shareholders were involved; the editor, publisher, chairman of the board and all the independent directors--including Michael, now Lord, Young--were kept in the dark. As a magazine which was always committed to casting light in dark places, NEW SOCIETY deserved better than that.