Various Authors

Chartist International No. 2

Editorial Comment: The stagnation of Marxist theory

Socialist Unity: Labour and the Far Left

General Condition of Class Struggle

Is Socialist Unity the Road to Revolutionary Unity?

The Socialist Unity Conference

Socialist Unity — On Its Own Terms

Socialist Unity and the USEC Theses on Britain

The Problems With Socialist Unity

Lowest Common Denominator Politics

Trotskyism and Sexual Politics

The Anthropology of Evelyn Reed

Hunting and the Power of Women

Cannibalism Violence and Male ‘Nature’

Review: Socialist Register 1977 & Ireland

Democracy and the national question

Contents

Editorial Comment

Socialist Unity — Labour and the Far Left by Mike Davis

Trotskyism and Sexual Politics by Martin Cook

The Anthropology of Evelyn Reed by Chris Knight

Review: Socialist Register 1977 and Ireland by Peter Chalk

Letter from S.Bornstein

This issue of Chartist International was produced by an editorial collective consisting of

Don Flynn (Convenor)

Jim Ring

Geoff Bender

Al Crisp

Martin Cook

Frank Lee

All correspondence and articles for consideration for the next issue should be sent to

Editorial Collective

Chartist International

60 Loughborough Road

London SW9

England

CHARTIST INTERNATIONAL is published twice yearly by an editorial collective consisting of members and supporters of the Socialist Charter.

The Socialist Charter has members and supporters in the following areas

Brent (N.London)

Brighton

Crewe

Derby

Hackney (E.London)

Haringey & Islington (N.London)

Hull

Leeds

Nottingham

Oxford

Stockport

Stoke

South London

For further details of activities etc. contact

The National Secretary

Socialist Charter

60 Loughborough Road

London SW9

England

Typesetting by Bread & Roses (TU) 01–485 4432

Printing by Anyway Litho Ltd. (TU) 252 Brixton Road SW9

Editorial Comment: The stagnation of Marxist theory

In the editorial in the last issue of Chartist International we referred to a problem which is at the heart of all debate and discussion on the far left today: the failure of Marxist theory to keep pace with the real developments taking place in the world in the period since the Second World War. In that issue we commented, “the after effects of the longest boom in the history of capitalism, the countervailing and contradictory tendencies at work as the system moves into crisis and the effects of these developments on the maturing class consciousness, all these imperatively demand of Marxists not satisfied with the stale remains of 40 years of stagnation in the Marxist movement, an answer to the question, ‘Through what stage are we passing?’”.

No group on the revolutionary left today can maintain the view that there have not been substantially new developments in the world balance of forces and within bourgeois society itself which have placed demands on our movement for a thorough-going reappraisal of the conditions that prevail today. Whether it is judged that these new developments have taken place in the realm of the economy, in the superstructure of the state and civil society, or in the psychological character of individual human beings as a consequence of the authoritarian conditioning of capitalist society, the tasks of this reappraisal have been taken on by some sections of the left.

In Britain alone a whole range of non-sectarian journals and magazines have been produced which have been probing and analysing areas of social, economic and personal relations which have not been approached by orthodox Marxists for decades. Particularly important in this respect are journals such as Capital & Class (journal of the Conference of Socialist Economists), Critique, Ideology & Consciousness, Race & Class, m/f (journal of socialist feminism) and the now well-established New Left Review.

However, the organised left, (that is, those organised into parties, leagues, groups etc.) have, in many cases, responded to these new developments in a typically ungracious way. The attempt to provide a class perspective for understanding the emergence in the post-war period of such things as a greatly expanded state sector of the western economies, the victory of anti-capitalist revolutions led by non-orthodox Leninist parties in China, Cuba, and Indo-China, the emergence of an international mass radical feminist movement, the growing consciousness amongst sections of society to sexual oppression, have all led to the epithets ‘revisionism’, ‘capitulation to bourgeois pressures’ etc., being flung about. These orthodox Leninists have a profound belief that the only political statements worth making are those which can be verified by the authority of a good number of quotes from Marx, Engels and Co. The bull-headedness of sections of the left on this score has succeeded in creating a new tyranny which has an inhibiting effect on achieving a proper dialogue and debate between people on the left. It is a tyranny which teaches the adherents of its own faith to actively distrust, and even espouse hatred for anything which seems like a new idea, particularly if it seems likely to cause us to challenge a few of the old ones.

Eurocommunism

Typical of this sort of response has been the reaction of the orthodox left to the emergence of Eurocommunism in the western Communist Parties. The standard description of this development is that it marks a retreat into reformism. According to this view, the desire to avoid the use of terms like Leninism or dictatorship of the proletariat on the part of these CPs marks an unqualified step back into social democracy. The conclusion drawn from all this is that nothing particularly new is happening: there is still social democratic reformism just as there always has been, only now augmented by the erstwhile CPs, and there is still the revolutionary left, battling for its principles and the integrity of the workers’ movement.

In reality, life is not so simple. There still remains a great difference between social democrats like Callaghan and Schmidt and even the most rightward-leaning euro communists like Carrillo or Berlinguer. These clear differences lie in the following areas. Social democracy (of the modern-day Socialist International variety) is, above all else, a pragmatic response on the part of sections of the working class and allied intellectuals to the day-to-day problems of living in a capitalist society. Its response to these problems is partial and one-sided, reflecting an overwhelming preoccupation with economist and welfare-ist concerns. It scarcely ever rises to the level of a coherently and consistently worked-out view of the world. If social democracy generates anything near worthy of the name philosophy, it is of a deeply utilitarian and empiricist variety.

Eurocommunism on the other hand, while at the level of tactics, places emphasis on non-revolutionary, reformist arenas such as parliament, participation in ‘responsible’ pro-capitalist governments, support for austerity programmes and even strong-state law and order, approaches these tactical questions from the initial standpoint of the overall problems of achieving the transition (or the transition to the transition) between capitalism and socialism. Now all this is undoubtedly very convoluted and Machiavellian, but it does not represent the adoption of a pure and simple reformist standpoint nor does it represent a continuation of the old Stalinist project of holding back the working class from revolution (as the traditional Trotskyist characterisation has it). On the contrary, the manoeuvres and stratagems of the CPs of Italy, Spain and France represent an attempt on the part of mass workers’ parties to come to terms with a new world balance of power and a new configuration of social forces within the advanced labour movements of western Europe.

A key element in the development of the Eurocommunist current has been its strong advocacy of democracy (at least outside of the ranks of the Eurocommunist CPs!) and its distance from the regimes of eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. While this has clearly meant an adaption to the traditions of liberal bourgeois democracy it has also meant that the debate about the nature of a socialist society, previously completely dominated by the existence of the east European states, has now been thrown wide open in the European workers’ movement.

For many west European communists the turning point came with the water-shed year of 1968. In a period of general radicalisation where new forms of struggle were being explored the CPs of France and Italy had to both appear as radical opponents of contemporary society, as potential parties of government and, above all, as opponents of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. This last point had a traumatic impact on the western CPs. There was no way that the pretence could be maintained that there was a ‘fascist rising’ threatening to overthrow the social conquests of the Czech people as had been the official line on the Hungarian revolution of 1956. It was brought forcibly home to the French and Italian CPs that their acceptability as parties of government and their appeal to radical workers and youth would depend increasingly on the distance they took from the policies of the Kremlin. In thus striking out on their own the western CPs were confronted with all the unresolved problems of socialist strategy in the advanced capitalist countries. Eurocommunism was, and is, an attempt to tackle these problems, in the debased and inflated currency of a Stalinised ‘Marxism’ — but, nevertheless, a genuine enough attempt.

Left’s response

It is not the purpose of this Editorial Comment to make out the case for or against Eurocommunism. This will need to be done elsewhere and at greater length. The point we wish to make is that to date, the orthodox revolutionary left has failed to produce an adequate account of Eurocommunism which can explain it in the context of a response on the part of mass working class organisations to the complex changes which have taken place in social relations at a whole number of levels and which have had the most profound effect on the labour movement of western Europe since the war. The only explanations we have been offered to date are that either the CPs have become standard reformist parties and hence we respond to them in the standardly prescribed way, or, that the whole thing is just a new deceit cooked up by the Stalinist bureaucrats in Moscow etc.

The consequences of these errors of gross over-simplification are very grave for the revolutionary left. For those groups who believe that Eurocommunism equals social democracy it has meant identifying opposition to the Eurocommunist currents as being relatively healthy radical-proletarian gut-reactions against a revisionist betrayal of Leninism. Hence the most reactionary, 1930-type ‘Moscow right or wrong’ thinking has been defended on the grounds that it appears to have a bit of working class ‘beef’ about it. The other side of this is that each and every comment of the Eurocommunist leaders is systematically dissected, analysed and revealed as further evidence of liberal social democratic infection. In this way, such groups as the extremely orthodox Revolutionary Communist Group can make such comments as ‘a corollary of this theory of a multi-party socialist state [expounded by the eurocommunists] is the abandonment of the concept of the communist part as a vanguard party of the working class.’ (Revolutionary Communist 6, April 1977) When revolutionary communists undertake to defend ‘one party states’ against the revisionism of the ‘democratic’ aims of the Eurocommunists one can only acknowledge the pitiful state of the revolutionary movement and ask just who are the ‘Stalinists’.

Such attempts to ‘analyse’ Eurocommunism fail altogether to explain anything to the working class. What is studiously avoided is the fact that the development of Marxist conceptual tools of analysis have failed to keep pace with the concrete developments in post-war social life. For all its failings, euro- communism represents an attempt to come to terms with this new reality. If we face up to this fact properly then we can see that a Marxist critique of Eurocommunism consists not in finding a place for it in convenient ‘reformist’ or ‘Stalinist’ pigeon-holes, but the extent to which it is a success or failure in achieving its own stated objectives — that is, to provide an updated perspective on contemporary western society which would provide communist workers with a basis on which they can operate in day-to-day struggles, with the ultimate objective of attaining the transition to socialism in mind. Orthodox Leninism has failed to provide a basis of this nature to the workers’ movement for the last thirty years. For the revolutionary left to offer this sort of perspective to the working class movement it will firstly have to effect a revolution in its own thinking. A major aspect of this revolution would revolve around the understanding that a definitive line of action is decided on through the process of a concrete analysis of the forces and social relations which exist at this present time. We should call for a complete end to the sort of ‘theoretical’ investigation which aims to prove that such and such a tactic/ programme/speech was wholly, partially or otherwise in accordance with the thought of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky.

****************

In the preceding Editorial Comment we have chosen Euro-communism to illustrate the half-hearted way in which the revolutionary left has attempted to analyse the situation today. We could have equally chosen the question of the emergence of a mass, international feminist current in the last two decades. Two articles in this issue of Chartist International attempt to deal in some detail with the way in which the revolutionary left has failed to develop its ideas on the issue of the sexual oppression of women in step with the world outside. Martin Cook, in his article Trotskyism and Sexual Politics, reveals something of the way in which the revolutionary communist movement, the Lenin-Trotsky tradition, has failed to play a role of any significance in developing a framework for understanding the place of sexual oppression in capitalist class society. This was not simply because the issue was not around in their own lifetimes: a generation before the birth of Bolshevism and the Third International, Marx, and particularly Engels in his work ‘Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State’ had given some indication of the importance which they attached to the problem of women as the ‘defeated sex’ throughout the history of all class societies. In the Bolshevik party itself Alexandra Kollontai spoke out as a clear advocate of feminist concerns in the Russian revolutionary movement. At a slightly later date, the German psycho-analyst Wilhelm Reich established the pioneering ‘sex-pol’ clinics in the periphery of the communist movement and produced a series of brilliantly clear statements which sketched out the reasons why the sexual health of individuals in the workers’ movement was of vital concern to those struggling for socialism. Irrespective of the early promise of the Marxist movement pioneering the way towards a clear scientific understanding of the nature and the consequences of sexual oppression, it has latterly actually lagged far behind and has even played a conservative role in many respects in this field. The detailed, radical critique of sexual oppression and sexual life in class society which has been attained today comes almost exclusively from a feminist tradition. Revolutionary socialists today have to learn to regard the achievements of feminism as something which, in most ways, they have to learn from, rather than to merely dissect it to reveal its ‘petty bourgeois’ character. Comrade Cook’s article goes a long way to providing a more sober assessment of the revolutionary left’s historical contribution to the struggle against sexual oppression than the exaggerated claims which are normally made for the communist movement.

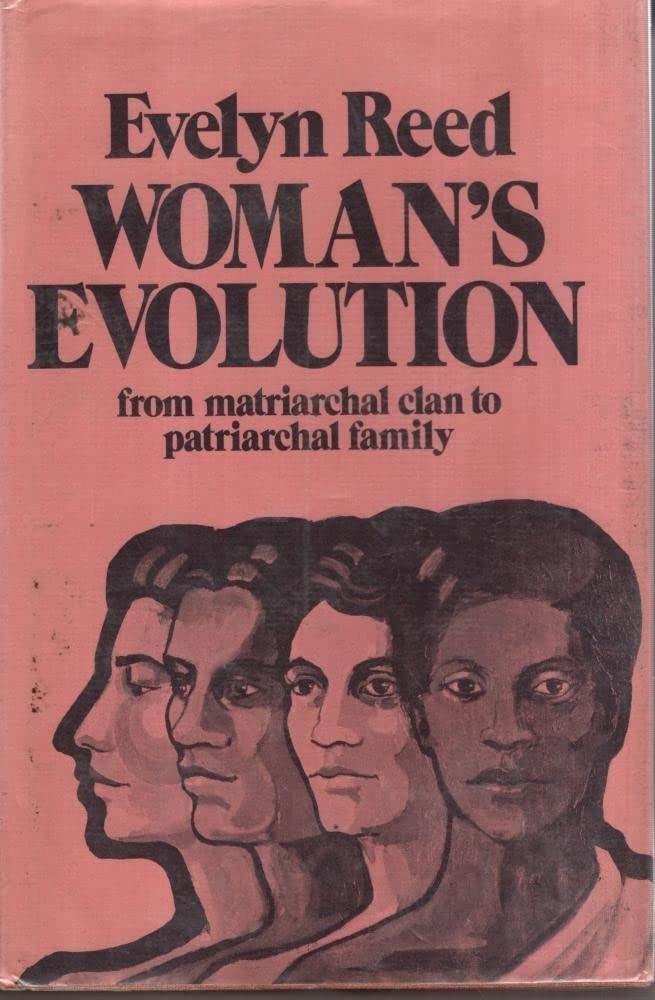

On a related theme, C.D.Knight’s article The Anthropology of Evelyn Reed attempts to deal with the claims of this veteran of the American socialist movement to have solved the riddle of the evolution of the human species and at the same time to have restored the female sex to its rightful place of honour in this process. Comrade Knight, in a strongly polemical style, draws attention to the inadequacies of Reed’s method in this respect, which he sees as having more in common with nineteenth and early twentieth century methods of anthropological discourse of which James G. Frazer and Robert Briffault are perhaps the prime examples. This style of anthropology is very deeply rooted in an extremely selective use of available evidence and a marked tendency to indulge in the grossest speculations. It has the dangerous attraction that, at an extremely superficial level, it provides some evidence for the existence of a matriarchal epoch in the course of human evolution.

The problem with Frazer and Briffault, on whom Reed leans for the bulk of the evidence for her theories (and even to a very large extent the more eminent figures of Lewis Henry Morgan and Edward Burnett Tylor , the acknowledged ‘fathers’ of anthropological science) is that the bulk of the empirical evidence on which they deduced their highly speculative theories has been proven by a later generation of researchers to be irrefutably false, beyond any reasonable doubt. Thus Reed’s extremely elaborate account of the early matriarchal society, which seems to be so clearly logical and appealingly simple, is actually based on the flimsiest foundation. The thrust of Knight’s position is that an argument which seeks to establish the existence of a matriarchal society which is based on such demonstrably incorrect evidence is not a service to feminism or socialism at all, it is a service to the enemies of these movements.

Knight does not abandon the idea of a matriarchal epoch, on the contrary, a thorough analysis of the problem based on the evidence of more contemporary, and more rigorously scientific anthropological theorists, such as Lévi-Strauss, despite the beliefs of these scientists themselves, points more clearly than ever in the direction of an epoch of primitive, communistic, matriarchal, societies. Following through this position it will be seen that the struggle to establish this revolutionary view of human society and human nature in its proper place, will be more centrally concerned with the ideological confrontation with the best and most scientific of bourgeois anthropologists who presently reject the view that matriarchal society ever existed, than in attempting to bolster the position of those few equally bourgeois anthropologists, who, on now totally outdated evidence, over sixty years ago happen to arrive at the notion that it might well have existed.

The brevity imposed on comrade Knight, by virtue of the fact that the article was intended for this brief journal, has possibly meant that the alternate argument in favour of the existence of matriarchy is not developed to the highest degree of satisfaction. To those of our readers who feel that more concrete evidence should be brought forward to back up this alternate view we can promise that we will be returning to this question in future issues of Chartist International. Also, comrade Knight is presently completing a full-length book which seeks to outline the major elements of a Marxist theory of the evolution of the human species which is expected to be ready for publication in the near future.

****************

Also contained in this issue is a review of the Socialist Unity project which has been instigated by a number of groups on the British left in an attempt to provide an electoral alternative to the Labour Party. Mike Davis’s article speaks for itself in providing a clear critique of the SU project in terms of the inadequacy of its programme, and the dangerous, damaging inconsistency of the main protagonists of SU, the Internationalist Marxist Group. In the course of a single year the IMG has switched its position from attempting to encourage and strengthen the work done by the socialist currents inside the Labour Party, to an attempt to present their own organisation with its allies in SU, as the alternative to those comrades they were previously attempting to assist in their struggles.

Another feature of this article is the statement of the Socialist Charter’s own perspective for building a revolutionary socialist tendency tendency inside the British labour movement. For our tendency, the struggle for socialism brings militants at every stage into conflict with reformism inside the working class, both as an ideology, as an organisation, in the form of the Labour Party and the trade unions. The absolutely hegemonic position which reformism occupies in all aspects of working class life makes the project of building a separate, independent revolutionary socialist organisation, outside of the day-to-day contact with the political battles inside the Party and the unions, utterly utopian. The standpoint of the Socialist Charter is that the far left should be struggling for their ideas inside the Labour Party, and that in undertaking this fight, we have to take part in the day to day battles of the working class. In the coming weeks and months advanced sections of the workers’ movement are going to be involved in the struggle to win votes for the Party to ensure that Labour is returned to office in the forthcoming general election. In refusing to stand in solidarity with these workers it must be said that the SU project appears as a gigantic diversion which cuts across real interests of the labour movement which are to maintain their present unity and to fight to strengthen the socialist currents inside the Party and the unions.

The final article in this issue of Chartist International is a review of the discussion on the struggle in Ireland contained in three articles in the Socialist Register 1977. Peter Chalk explains why the ten year long most recent episode of the ever-recurrent Irish Troubles can only be understood in the context of the struggle to unite the Irish nation. It is only in the context of a united Ireland that the Irish people can exercise a genuine right of self-determination in opposition to the forces of world imperialism. Readers who find this viewpoint of particular interest might like to refer to the journal Ireland Socialist Review, which is advertised elsewhere in this journal, which contains other articles written by members of the Socialist Charter.

Don Flynn

28.5.78

Socialist Unity: Labour and the Far Left

By Mike Davis

“The Communists do not form a separate party opposed to other working class parties. They do not set up any sectarian principles of their own by which to shape and mould the proletarian movement.”

Marx and Engels: The Communist Manifesto

The ‘success’ of the Labour Government in carrying out many of the anti-working class policies the Heath government had been unable to implement has produced a contradictory movement amongst socialists and working class people. From the millions of Labour supporters who voted for Labour in 1974 has come a response initially of enthusiasm, then confusion and bitterness as many of the goods promised failed to materialise, and most recently a new surge of loyalty and support blended with an aroused anti-Tory, anti-fascist sentiment. From more class conscious workers and militant socialists, especially those on the revolutionary left, the inability to challenge successfully the right-wing, pro-capitalist policies of the Labour and trade union leaders reflected in the non-appearance of ‘mass action’, has come a mood which is searching for ‘unity’ and regroupment of revolutionary groups and individuals.

Many socialists not aligned to any particular revolutionary organisation, and indeed many who are members of working class political organisations, often comment on the splintered, fragmented and apparently sectarian character of the revolutionary groups (more than twenty groups today claim a heritage from Trotskyism in Britain). It is a confusing and off-putting picture for many. Yet, socialist or workers’ unity is a notion which few but the most inveterate bullheaded sectarians would dissent from. Unity unfortunately is both a much misunderstood and much abused concept on the left in Britain. It is not simply sufficient to declare oneself for unity but to know exactly what measure of unity already exists, how further unity can be built and what is the nature of the political divisions which separate the movement for socialism organisationally.

Conceptions of Unity

This article will attempt to critically examine a particular approach to the problem of unity. Namely the project of Socialist Unity (SU) which seeks both to unify socialist groups and militants and unify an opposition to the Labour Government. We will look more closely at what exactly is meant by working class unity and revolutionary regroupment, and the efficacy and correctness for revolutionary socialists to stand candidates against the Labour Party.

Socialist Unity represents a very different conception of unity and one which we will argue stands in counter position to the already existing workers unity, which despite its social democratic political character, should not be underestimated. It has been argued that “Socialist Unity corresponds to the needs of the class struggle at the present time for unity.” We would argue that on the contrary SU flies in the face of these felt needs on the part of millions of working class people for unity in their ranks, by denying in practice the importance of the Labour Party and the almost instinctive drive to maintain that unity embodied in the Labour Party and its relation to the trade unions (a sentiment so ably exploited by the “social contractors”).

An historical approach is missing from SU’s conception of the problems of unity. Although the Labour Party has a pro-capitalist leadership, it nonetheless represents an immense historical gain for the British working class and a conquest from which nothing should blind us. Workers in the United States of America, for example, have never been able to create a Labour Party of their own, and are forced to choose between two openly bourgeois parties: that is, between the devil of the Democrats and the Republican deep blue sea.

With the creation of the trade unions and then the Labour Party, the British working class achieved a very real historical conquest. Within these organisations are concentrated the broadest range of opinions, ideas and perspectives for socialism. Notwithstanding the marginal decline in membership of the Labour Party, in 1974 more than eleven million working people turned out to vote Labour. Seven million trade unionists are affiliated to the Labour Party and their union dues are the financial backbone of the Party. Despite the record of the present Labour Government, we have recently witnessed renewed support and electoral success for the Labour Party in Scotland and the North which has confounded the pundits and their swingometers. Traditions and common ideological world views are too easily overlooked by the shallow observer who sees a “void” or a “vacuum on the left” where historical movement allows for no such theoretical niceties.

Thus it is the unity established in the Labour Party and trade unions, a form of workers’ unity, that a revolutionary tendency needs to build on, explaining in words and deeds their Marxist policies in a living relationship with the very organisations in which and through which the workers perceive their own problems. The conflict of ideas in the Labour Party, the struggle between left and right, the fight for democracy in the movement are fundamentally the struggles within the working class itself for a way out of the crisis.

We will examine other aspects of this, the fundamental problem of workers unity, during the course of this article. But Socialist Unity claims not only to stand for workers unity but also for unity of the revolutionary left regrouped in one unified revolutionary organisation under the umbrella of the United Secretariat of the Fourth International. And it is in this light, as we have indicated, that Socialist Unity (SU) has attracted the greatest amount of publicity and paper support as a “unity project”. The organisation which has been most conspicuous in advocating the need for a “unified revolutionary organisation” (not of course the only one) has been the International Marxist Group (IMG). Unfortunately, over the last eighteen months, the IMG’s whole perspective of revolutionary unity seems to have been narrowed continuously down to the point where Socialist Unity as an electoral organisation/grouping has become visibly the only focus in and around which revolutionary regroupment can take place — aside from selective discussions in the paper Socialist Challenge.

General Condition of Class Struggle

Most active socialists now recognise that since 1975 and the emergence of the social contract a significant downturn has occurred in the tempo, militancy and unity of working class struggle. The Labour Government, elected in the midst of the deepest capitalist crisis since the second world war, has imposed defeat after defeat on the working class. Three years of wage restraining incomes policy. Three years of public expenditure cuts. Almost three years of unemployment of over 1 million (unofficially up to 2 million). Sacrifice and ‘national interest’ under the banner of the social contract and the great crusade against inflation have been the catch- phrases for inflicting cuts of over 20 per cent in the living standards of working class people.

In circumstances of defeat and impoverishment, little wonder that the poison of racialism and sexist prejudice floats to the surface and is fully exploited by the capitalist media, the ruling class and its political representatives. Fascism, in the shape of the National Front, also rears its ugly head from the sewers, striving to deepen the division amongst the working class and oppressed and incite white against black, non-communist against communist.

Of course workers have attempted to resist the policies of the Labour Government and TUC cohorts. But the resistance has been sporadic, fragmented and localised. The Grunwick struggle, the opposition to the closure of the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson women’s hospital have stood out like towering rocks in this ebb tide. Where the trade union movement has been able to break out of localised struggle, such as in the firefighters strike against Phase Three, the trade union and Labour leaders coupled with the weakness of the ideological alternatives to wage restraint have combined to isolate and defeat the workers.

Light in the tunnel is clearly now showing in the anti-racist and anti-fascist struggle, which has recently reached a new peak in the magnificent 80,000 strong demonstration and Carnival against the Nazi NF and racialism. Possibly the beginnings of a firm united front against fascism?

But here is not the place for detailed analysis of these movements or the character of the downturn in class struggle (see Chartist International No. 1 ‘Political Perspectives’ for fuller treatment of this). We wish merely to address readers to the general state of class struggle in order to show that the problem of revolutionary regroupment and workers unity cannot be divorced from the general fight for a workers united front against capitalism.

Background to Socialist Unity

When Socialist Challenge itself was launched, an editorial in its forerunner Red Weekly on May 19th declared:

“Socialist Challenge will make its central goal the fight for an organised socialist opposition to fight the effects of the capitalist crisis. And it will be in the forefront of the campaign for a principled regroupment of the revolutionary left.”

Put in these terms, such an aim is one with which most serious revolutionary tendencies would be hard put to disagree. But the problem only begins here. As we have argued in other publications on the Trotskyist movement, the main problem for ‘Trotskyist’ organisations has been their isolation and fragmentation, virtually from the inception of ‘Trotskyism’ as a faction within the Third International. This was in part due to adverse politico-social conditions (defeats of the 1930s, destruction of cadres in Second World War, the postwar boom etc) and equally the theoretical and ideological confusion of Trotsky’s epigones and the limitations of Third International Marxism when applied to a complex, bourgeois-democratic, expanding post-war capitalist west.

The late sixties/early seventies upsurge in class struggle in the western capitalist heartlands produced a mushrooming of many new tendencies to the left and not so left of the Communist Parties. It was in this context that the question of “unity” was again sharply posed in the post war period.

The International Socialists (SWP) led the first “unity call” in 1968 as an immediate option to fill “the vacuum on the left” following Harold Wilson’s betrayals. Only Workers Fight responded to the call, The attempt was ended unceremoniously in 1972/3 with the successive expulsions of the Trotskyist Tendency (Workers Fight, now the International Communist League), and the Revolutionary Opposition a year later. No attempt was made to clarify political differences and perspectives which had produced the fragmentation in the first place.

Today the IMG proclaims itself as the champion of regroupment and “left unity”. As always, the problem is however, how is this unity to be achieved? We have always tried to stress in our own documents (maybe not always very well), that in such a period of fragmentation and crisis for Marxism only strict political and ideological demarcation, a willingness to admit mistakes, to admit none of us have a monopoly of wisdom or all the answers, a fraternal discussion of differences on analysis and method, concepts, perspectives and programme could provide a sufficient basis for enduring unity. Though this must always be combined with a preparedness to engage in joint activity. As we said in a balance sheet of discussions with the IMG in 1976:

“Unity on an unclear, un-Marxist basis was building on quick-sand. Any \such ‘unity’ would spring apart like a broken watch at the first real test of great events.”

Whilst it is true that sectarianism, expulsions and unfounded splits have added to the general fragmentation of the British left, the fundmental reasons for the divisions of the Trotskyist movement lie more in the conditions of the post-war period and the failure of the early formations to satisfactorily develop Marxist analysis of social and economic conditions and maintain a correct relationship to the working class and its organisations. Parallels do exist today between our struggle for unity and those of Trotsky and the Left Opposition in the early 1930s, when the Marxist movement was suffering a similar process of fragmentation. Quotations are never a very accurate way of presenting ideas because they are always dated by historical circumstances and specific conditions, but this quote from Trotsky seems apposite to the current problem of recoupment:

‘The Opposition (Left Opposition) is now taking shape on the basis of principled ideological demarcation, and not on the basis of mass actions Mass actions tend as a rule to wash away secondary and episodic difference and to aid the fusion of friendly and close tendencies. Conversely, ideological groupings in a period of stagnation or ebb-tide disclose a great tendency towards differentiation, splits and internal struggles.

We cannot leap out of the period in which we live. We must pass through it. A clear, precise ideological differentiation is unconditionally necessary. It prepares future successes.” (Trotsky: Groupings in the Communist Opposition, 1929)

Is Socialist Unity the Road to Revolutionary Unity?

On the surface, the initial aim of Socialist Unity appeared to be to provide a forum for grouping together various revolutionary socialist groups and individuals to discuss unity in the context of specific actions against the attacks of the ruling class and its Labour allies. But increasingly it became clear that Socialist Unity was not merely the main focus for revolutionary regroupment but that it would operate almost solely around the question of standing candidates against Labour in elections. In other words, Socialist Unity puts the cart before the horse. In the fashion of classic opportunism, all the issues that divide the Trotskyist movement are swept aside or reduced to trivia and replaced by an activity-orientated grouping for electoral unity. Essentially, the IMG has drawn a line on the issue of a tactic of intervention — the vague concept of “class struggle candidates against the Labour Party”; those on one side agreeing with this shallow and vague concept and the rest of the left on the other.

The divisions of Trotskyists and other revolutionary socialists are reduced to one question: “standing candidates against the Labour Party”. How any kind of clarity, firm foundations for unity and serious discussion can occur on this basis defies the imagination.

That Socialist Unity has become the primary and apparently only focus for revolutionary regroupment has become clear over the last few months, both in the columns of Socialist Challenge, in the actual emphasis on electoral interventions and search for common candidates with the Socialist Workers Party, and from the first and to date, only conference of Socialist Unity on November 19th 1977.

The Socialist Unity Conference

This Conference, attended by approximately 200 people, highlighted most of the dilemmas confronting an approach to socialist unity — small ‘s’ and small V — which is both sectarian and opportunist. Socialist Unity has the support of the IMG, the Big Flame group, Martin Shaw (an ex-International Socialist [SWP] ex-student leader) and other members of the Hull Socialist Alliance (an amalgam of aligned and non-aligned socialists), some socialist feminist groups, some organised Asian socialists and libertarian Anarchist groups. At the conference itself the Workers League were present in a supporting capacity as were some Maoists from the obscure Communist Formation.

In the Bulletin for the Socialist Unity conference we were informed that,

“The Conference is open to all organisations and individuals who support the concept of standing class struggle candidates, standing on an alternative socialist programme in selected constituencies and wards in elections, parliamentary and local.”

Immediately after this statement we were told,

“All people attending the Conference and accepting the above premise will be allowed to speak and vote.”

And herein lay the proverbial rub. At no time has there ever been a conference or open meeting of SU to discuss the meaning of “class struggle candidates”, and least of all the programme on which such candidates would stand. And yet from the outset, members of the International Communist League, Socialist Charter and International Spartacists were prevented from speaking at the conference (so too we believe were Workers Power) on the grounds that these tendencies disagreed with a concept and a programme that had never been discussed outside the confines of internal IMG or Big Flame meetings.

Without labouring further the point that Socialist Unity represents the narrowing-down of the basis for revolutionary regroupment to an electoral tactic, let us examine SU on its own terms.

Socialist Unity — On Its Own Terms

Prior to the November 19th Socialist Unity Conference, a Socialist Challenge article had reported in rather grandiose terms that “Last week’s Labour Party conference ended on a note of tranquillity.... the Socialist Unity conference being held in London on 19th November now becomes even more important as a focus for organising a fight-back against the attacks of the ruling class and their Labour allies.”

At the SU conference itself Bob Pennington (IMG, now SU organiser) summarised the position of the IMG leadership on the future of SU:

“How does SU serve and fit into the interests of the working class at present? Capitulation characterises the existing leadership. Lefts don’t mobilise support for their policies.

The CPGB is the same because the main strategy is an alliance of the lefts.... therefore there is no struggle. This has left a void, a gap. How does the working class and its allies start a fightback? Those who want to fight can be given an alternative programme and organisation. Not party building but (1) SU corresponds to the needs of the class struggle at the present time for unity and, (2) SU has a preparedness for open dialogue and debate.”

Pennington went on to stress the dangers of “overstructuring” SU and located SU firmly in the context of the “class struggle left-wing project”. “I’m in favour not only of class struggle candidates”, he emphasised, “but also support for those who don’t stand on a SU platform. For example, if a woman stood on a NAC platform I’d be in favour of that, or an anti-racist.” ‘The key”, for Pennington, “was SU campaigning for unity and a break with left-sectarianism”. The hopeless shallowness of these words we will show shortly.

More recently, on the eve of the Lambeth Central by-election in South London (in which the SU candidate received 287 votes to Labour’s 10,311), the editorial in Socialist Challenge (20.4.78) carried the headline “Labour and Socialist Unity”. The editorial posed the following questions in an honest mood of self-examination.

“Why do we stand candidates against Labour? Are we an alternative? What is our central slogan for the General Election?”

The editorial managed only to attempt answers to the first two questions, contenting itself with a reply to unmentioned abstentionists by reiterating its call for a Labour vote in the remainder of the editorial.

What reasons does Socialist Challenge give for standing Socialist Unity candidates?

“We stand candidates against Labour because we believe that it is essential to project a socialist alternative in local and national elections; to try to catalyse a current which is sympathetic to socialist politics. More than that they offer militants who are fighting for class struggle politics an opportunity to show through their campaigns and struggles how their policies are the ones which take the fightback forward ”

As an afterthought we are also told that “elections also help us to have a dialogue with the masses — a beneficial experience.” In an article on Socialist Challenge on 9.2.78, announcing Socialist Unity’s intention to stand 60 to 80 candidates in the May municipal elections, we were told SU also “insists there is a need to fight back now” against Callaghan’s Government.

Socialist Unity and the USEC Theses on Britain

In the midst of the euphoria arising from the Socialist Unity ‘project’, the votes cast, the selecting of candidates, the campaigning, it is worthwhile to look back, first of all, to the last published United Secretariat of the Fourth International Theses on Britain, which appeared in the IMG’s theoretical journal International, (Vol 3, no. 1). Here we find a much more sobering comment on the British class struggle and the lack of any mass struggle against the then Wilson-led Labour Government (a situation which we might add, has continued and looks set to endure for the duration of this Labour Government).

“While a challenge to the Labour Party at all levels, including electorally, will be necessary for the final historic defeat of social democracy, the break of the British working class with social democracy is very unlikely to take the form, in the near future, of the setting up of a rival mass party or of a significant challenge to the Labour Party by the revolutionary left on the electoral field. This break will much more likely take the triple form of a turn away from parliamentary and electoral politics without an organisational break with the Labour Party as such of united actions of a broader and broader vanguard, both within and outside the Labour Party; and of a deeper and deeper penetration of revolutionary socialist and communist ideology among the rank and file trade unionists and Labour Party members.” (our emphasis p.16).

The theses then went on to outline a very different kind of perspective for a united and non-“left-sectarian” fightback against the Labour Government, than that advocated and embodied in the whole Socialist Unity project.

“Under these circumstances, [of an incipient but still small-scale conflict of militants with the Labour Government] where every objective development creates the need for a generalised political response and leadership of the working class, but at the same time the overwhelming majority of even the most militant workers still give their political allegiance to the Labour Party, such a leadership and political perspective cannot be created in the immediate future — the coming 12–18 months which is the time period posed — outside the Labour Party, if it is to be credible and acceptable to larger sections of the working class. The whole pressure of the situation is thus to the creation of a challenge to the leadership of Wilson-Murray-Jones inside the Labour Party and the labour movement.... The task of revolutionary marxists in Britain is not mechanically to counterpose themselves to this process, which in any case they are powerless to alter but to ensure both that even those workers who do not yet break with their illusions in the Labour Party adopt the most advanced demands and methods of struggle possible” (our emphasis, p.14)

This extract displays two major weaknesses. On the one hand a crude objectivism based on a methodologically wrong conception of the inexorable ‘objective’ movement of the working class towards an explosion — which of course has not occurred and is most unlikely to occur under this Labour Government. On the other hand, what this metaphysical “pressure” and “objective development ’’ignores and denies is the level of consciousness and activity of the working class itself which was and is a far throw from the generalised challenge to the existing leadership of the labour movement mechanically prescribed by the USec Theses. Nonetheless, despite the hugely over-optimistic time scale and one-sided catastrophic perspective for the development of mass opposition to the Labour Government and the premise for revolutionaries being in the Labour Party (a growing left- wing) which we reject, the Theses at least tried to grapple with the reality of the Labour Party for millions of workers, and outline, however inadequately, a perspective for united front work with Labour Party members. This approach to unity is indeed far remote from the electoralism of Socialist Unity.

It was a perspective which many IMG members and supporters attempted to implement, by re-starting some patient political work in the rank and file of the Labour Party. Work that the IMG had abandoned in the late 1960s following the growth of mystical “new mass vanguards”.

The tactic of standing candidates in elections against the Labour Party was given no emphasis or airing in the 1976 Theses — which are presumably the guiding lights for the IMG’s work in Britain. This leads us into the real problems with Socialist Unity on its own terms.

The Problems With Socialist Unity

The United Secretariat Theses presented a perspective of struggle against the Labour Government from within the Labour Party. It is a perspective that has significant bearing on reality. Namely, that despite its right-wing, class collaborationist policies, the Labour leadership is based on a Labour Party which is the only mass political organisation of the British working class. Whether that Labour Party is awash with millions of active members or not is really the wrong question. The fact is, it is the party to which millions of working class people and trade unionists traditionally turn as an alternative to the Tories. More than that, the illusions which are the bedrock of social democratic policies are shared by millions of these same working class people, who have by and large been prepared over the last few years to go along with the social contract and the parliamentary road to change.

The USec Theses, at least in part, gives cognisance to this situation. Unfortunately, Socialist Unity operates on a different perspective, presenting a different picture of the situation. This is the first question which the IMG should at least attempt to answer.

We disagree with the USec Theses that work in the Labour Party is an episodic tactic, but it is an improvement on the Socialist Unity position, which whether it has the support of individual Labour Party members or not, can only appear as a sectarian grouping to the vast majority of Labour members and supporters. More importantly, it is a diversion from the main struggle in the Labour Party against the dominant policies and leadership (a la the USec Theses) and an obstacle to those Socialist Challenge supporters who are trying to do some serious work in the Labour Party.

We would now like to pose a series of questions to SU supporters:

-

What prevents you putting your politics forwards in the rank and file Constituency Labour Parties? In Lambeth Central over 100 people came along to a Socialist Unity meeting. Such numbers would significantly alter the balance of power in the Lambeth Central CLP, if not become a dominant force when coupled with the existing socialists in that CLP. You would appear to be standing for the unity of the local labour movement, actually strengthen that unity in practice and be listened to by a much larger range of Labour supporters than would probably listen to Socialist Unity. The experience of struggle against the existing right-wing supporters of the Labour Government’s policies in that area would certainly take the “fight-back forward” a hundred times more than the 287 votes cast for the SU candidate, and would be educating those involved in the struggle against social democratic policies.

-

What about IMG/Socialist Challenge supporters in the Labour Party trying to do serious united front work with other LP militants? What possible help can SU be to these militants? It can only unnecessarily impede their activity by them being identified with a sectarian grouping with little or no base in most areas. Has there ever been any open discussion in SU about the problems standing candidates against the Labour Party poses for those Socialist Challenge supporters actually working in the LP? it would appear they are just to muddle through, denying their political affiliations, muttering favourable words or staying silent about SU, and downplaying the importance of consistent work in the Labour Party.

-

How is SU to show militants “how their [Socialist Unity] politics are the ones which can take the fightback forward? If it is by issuing independent propaganda then that can be done through the Labour Party. In many constituencies during the recent council elections, thousands of LP Young Socialists’ leaflets opposing racism and immigration laws, cuts, unemployment etc. etc. were distributed. Anti-Nazi League literature was distributed. Many other kinds of campaign literature was also distributed on various issues, like abortion rights and nursery facilities. In many cases, it was as a consequence of patient work through local CLPs that actual election material itself contained many policies that revolutionary socialists would not disagree with.

If it is not by propaganda, then in what other way can the “fightback” be taken forward? Perhaps through the votes cast. But it has yet to be shown how a few hundred votes can take a struggle forward. In analysing voting returns it is very difficult to say just exactly what proportion of votes were protest votes, miscast votes and votes for a fight-back. That an inveterate sectarian organisation like the Workers Revolutionary Party could gain 271 votes in Lambeth Central says mountains about the importance of those votes. Gr that a pop singer like Jonathan King can poll over 2,000 votes in a by-election as a ‘Royalist’ candidate. There are great dangers in extrapolating from votes of a few hundred anything of great significance. But more importantly, votes should not be confused with a fight-back.

The only aspect on which a fight-back could be said to have been boosted is on the level of campaign organisations, which nine times out of ten already existed or could have been generated through working in the Labour Party. For example, anti-racist committees, abortion groups, nursery campaigns, anti-cuts campaigns etc. This leads on to a fourth and fifth problem which came up at the Socialist Unity Conference.

-

How can Socialist Unity avoid reproducing the practices of any bourgeois election campaign? Several speakers at the SU conference, including Raghib Ahsan (who has four times stood as an independent socialist candidate in the Birmingham area, and most recently in the 1977 Ladywood claimed with great disappointment that SU parachuted in for a three-week blitz election campaign, primarily on a single issue i.e. anti-racialism, and then all-but disappeared. He said that no serious black work was being done in Birmingham (at the time of the conference, itself several months after the by-election) by SU or the IMG, no consolidation had been done, no political follow-up made. Ahsan put it down to lack of discussion and a deficiency in programme. But it is clearly much more than this. At root is the weakness and small size of revolutionary forces. The unpalatable fact of the matter is that revolutionaries have not yet done one ’nth of the serious political work in local areas to build up sufficient support in the mass organisations to even prove the case for standing against the Labour Party. Clearly, the base chosen in Ladywood was that of the immigrant community, whose political allegiances are not so defined as many white workers, and the vote gained did not represent any serious incursion into the white largely racist Labour vote.

-

The other horn of this dilemma was also pointed out at the SU Conference by Paul Thompson of Big Flame. Namely, the political content of consistent work, and the various constituent tendencies of SU going away after an election campaign and working for the politics, perspectives and analysis of their own organisation. On the one hand the Libertarian Communist Group selling their Anarchist Worker, Big Flame with Big Flame, IMG members with Socialist Challenge, having their own specific brands of politics. It may be that nothing fundamental divides these groups, but differences should at least have been debated openly and thoroughly in advance, before a “common programme” is put to workers and on the basis of which campaigns will supposedly be waged, and action taken. The SU voter who supports the SU programme expecting action or consistent work for its politics, will be unpleasantly surprised to find varying types of action being mounted on one hand and on the other, the SU does not even exist outside of simple electoral action. As an International Communist League leaflet put it: “SU’s programme may serve for election addresses, but it obviously doesn’t serve to map out precise guidelines for action in the class struggle.

-

Bob Pennington, SU organiser, says “Socialist Unity has a preparedness for open dialogue and debate” and a democratic selection procedure. But in many respects it fails even to meet the standards of the Labour Party at constituency party level. Take for example the Lambeth Central by-election. A few weeks before the election it was decided to stand a SU candidate. Yet the first position SU took was the ludicrous one of support for the West Indian Bloc (WIB) whose politics were as vague and unknown as the ubiquitous Bill Boakes. A week or so later the WIB split with a large section declaring support for the Liberals as the only major party to condemn the Select Committee Race Relations Report and opposing the extremists of the left.

The selection of a SU candidate in Lambeth occurred in the space of about three weeks with two main meetings and overtures to the SWP. The process through which the Labour Party candidate, Tribunite John Tilley, was chosen had occurred over a period of six months with ward/branch selection conferences throughout the constituency, shortlisting, interviewing and questioning and then the final selection of the candidate at a special delegate meeting of the General Management Committee.

The implication of Bob Pennington’s comment is that the Labour Party is a reactionary mass. We have no wish to deny the non-democratic aspects of the Labour Party, but distortions for political expediency are totally misplaced. It will possibly be surprising for comrade Pennington that the dialogue and debate that is supposedly the private possession of SU has raged throughout the four Lambeth CLP’s for several years now and resulted in the shift to the left in these CLPs. To the point moreover, where Lambeth council is now seen as a left-dominated council and its leader was seen by Thatcher, in a question in Parliament, as a Trotskyist infiltrator But perhaps the debate and dialogue which characterised the Lambeth CLT is not the sort of exchange the SU organiser is seeking. Perhaps SU seeks to reach out to even broader untraversed stretches of the working class that the Labour Party cannot reach with its meagre resources and influence.

-

The Socialist Challenge editorial says that elections “help us to have a dialogue with the masses.” Once again, all elections provide revolutionaries working in the Labour Party with an opportunity for mass canvassing, mass leafleting and a “dialogue with the masses”. Indeed this sort of dialogue could have been conducted on a much bigger scale had not those revolutionary organisations who worked within the Labour Party in the 1950s and 1960s withdrawn from this arena of struggle, just at the time when the working class was beginning to flex its muscles and awaken from the quiescence of the post-war boom years.

When campaigning in elections, Socialist Charter members and Chartist supporters have argued for those Labour Party policies which would improve the conditions of the working class for example, the anti-racism policy passed at the 1976 conference, the pro-abortion on demand policy, the advocation of full employment and expansion of public services contained in the 1974 Election Manifestos etc. Those policies which hold back, confuse, mislead or compromise the interests of working class internationalism we oppose and argue against, for example, on wage controls, Ireland etc. Despite the fact that the Labour Party might not correspond to a model of workers democracy in most constituencies members are. not gagged when campaigning.

-

The Socialist Challenge editorial talks about “catalysing a current sympathetic to socialist politics”. In the same issue a report of the progress of the Lambeth Central by- election campaign talked of SU’s alternative policies helping “Labour Party members disgusted with the positions of their party leaders and candidate.” The question that needs to be asked is: how does it help these members and how does it develop a “current sympathetic with socialist politics?” As we have already tried to show, the lack of a base in most areas prevents SU effectively following up any ‘lightning’ election work. But more important, the perspectives of SU fails to arm Labour Party militants with a political strategy which can assist them not merely in breaking themselves from reformist or left-reformist politics, but also winning others from them. Instead of leading to sharper ideological/political struggle within the Labour Party and other organisations, SU elevates itself as the alternative organisation through which these militants can fight the Labour leadership.

The problem is that most workers learn through their own experience. But that experience and learning how to fight reformist policies and leaders, and does not take place overnight, or even through an election campaign. It involves a lengthy period of propaganda and agitation on different levels. When Lenin wrote Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder he pointed out that whilst disgust and outrage at the politics of the Labour leaders was an important component involved in the development of revolutionary Marxists consciousness, it needed to be trained in the forge of united struggle within the Labour Party itself. In other words, millions of workers look to the Labour Party for a lead. The job is to involve these workers in the struggle, in the Labour Party, unions etc, by patiently working alongside them, fighting for revolutionary politics whilst trying to build the unity of the workers organisations — most importantly, the trade unions and Labour Party.

-

There are no short-cuts in the fight against social democratic politics. Yet, no sooner do Socialist Challenge supporters commence what appears to be consistent work, trying to call the Labour leaders to account for their policies, than in many areas they abandon this work. This can be seen for example in Southall CLP. But come the Greater London Council election campaign, the promise of a few hundred votes from disaffected Asians for an independent candidate on anti-racist ticket was too much to resist. So the fruits of what work had been done were thrown to the four winds and Socialist Challenge supporters threw themselves into what was then the IMG candidates’ campaign, abandoning the struggle in the Labour Party in the process. Today, of course, when calls are made for Southall Labour MP Sidney Bidwell’s removal, for supporting the anti-immigration Select Committee Report, Socialist Challenge supporters are in no position to actually influence that decision. Similar sound work and then a sudden or ultimatist withdrawal from the Labour Party occurred in Hull Central CLP and other areas.

The view that black or Asian workers don’t have bourgeois democratic illusions or beliefs is a myth. In fact, whilst these workers might not have the traditional commitment to the Labour Party’s particular brand of social democracy — their ideas about the parliamentary change, gradualism, a neutral state etc. which underpin reformist politics, exist in similar measure. The building of fraternal relations with immigrant organisations, and encouraging membership of the Labour Party, as is being done with the Peoples National Party of Jamaica, is a method much more effective in fighting racialism in the Labour Party, challenging reformist views and strengthening the unity of action of black and white workers.

-

The final, and in some ways most important problem with Socialist Unity is its programme — or rather election address — which we reprint as an appendix. We say election address because in all the elections that SU candidates have contested, the original ‘programme’ adopted at the November 19th Conference, has been reprinted in varying forms as an address. Virtually all the policies and demands contained in the address we would support. But the real problem is that they do not constitute a programme. A real programme should contain an analysis of the current situation in Britain against the background of world capitalism. Equally, it should also contain a strategy and series of tactics which guide and direct people who want to know how to fight for the policies outlined in the election address. The ‘programme’ of SU fails to explain and fails to provide a united working class alternative.

Lowest Common Denominator Politics

At the Socialist Unity conference the debate on what turned out to be an election address, produced a confused series of haggles and compromises. Should the ‘programme’ demand workers control of bankrupt industries, nationalised industries or all. Should it demand a class size of 20 pupils. Should it support self-determination for Scotland; access for trade unions to the mass media; abolition of the House of Lords and Monarchy. Should the programme defend the “democratic opposition in the workers’ states” and so on. This kind of debate was cut short at the conference by the view that SU’s programme “cannot be an endless: list satisfying our ideological consciences” (Paul Thompson, Big Flame), but something that can be put through letterboxes. David Jones (IMG) summing up said SU should have two types of programme — a kind of election address and a kind of ‘British Road to Socialism’ produced as a pamphlet. The latter kind of programme has yet to materialise.

Conclusions

What we have tried to do in the preceding ten points is to illustrate some of the internal contradictions and inconsistencies with Socialist Unity on its own terms. But when we return to the fundamental questions of revolutionary regroupment and workers unity with which we started we find that Socialist Unity marks a sectarian step away from this problem. In short, if you don’t accept the electoral tactic of opposing Labour in elections — without question (because there was no forum provided to discuss it) — then you are precluded from the debate about socialist unification. And from this tactic (which appears to constitute the primary means of intervention in the class struggle) flows the programme. Tactics determine programme in this topsy-turvy method of revolutionary politics. Many serious revolutionaries might well ask how this squares with a Marxist methodology.

At the Socialist Unity conference, where discussion on this tactic was not permitted, a leading IMG member posed the question:

“Is Socialist Unity the framework for revolutionary regroupment? Or is it the framework for building a class struggle left wing?”

Although her question remained unanswered, the practice of the SU campaign reveals that it is neither. The truth of the matter is that the collaborating tendencies are approaching the problem from the wrong end: telescoping differences of analysis, programme and perspective, producing a sectarian attitude to serious Labour Party supporters and militants, to revolutionaries who see the need to work consistently in the mass organisations, and to revolutionaries who have a different view of revolutionary regroupment and want to discuss it. This applies particularly to those who do not believe the tactic of standing in elections will advance the process of unification.

This does not mean that Marxists oppose the standing of candidates for all times and on ail occasions. On the contrary, we are firmly in favour of standing candidates — but as Labour Party candidates on revolutionary politics An alternative candidate for Marxists does not mean being able to offer the masses a new name, a new organisation, with its address, telephone number and headed note paper. It means offering a political alternative.

When revolutionaries have developed clearer Marxist analysis and broader base through the existing organisations of the labour movement (and those of the specially oppressed), in other words when we are actually beginning to break out of political isolation from the mainstream views of the labour movement, then a basis will exist for a real challenge to the Labour leaders on both a local and national level. Such a perspective will not merely strengthen and educate the workers’ leaders of the future but deepen the already existing unity of the working class on much more militant class struggle foundations.

The real task facing Marxists serious about regroupment and unity is the clarification of these revolutionary politics, the cornerstones of which must be a Marxist analysis of reformism and Stalinism and corresponding strategic and tactical orientations, a non-sectarian attitude to the trade unions and Labour Party, consistent internationalist work against the special oppression of women, blacks and gays including sexual politics generally. These are the rudimentary issues on which a tradition of revolutionary Marxism must be established.

On its present course, Socialist Unity can only serve to obscure and obstruct the comradely, principled and non- sectarian approach to regroupment of the divided revolutionary movement. Empty sloganising and electoral expediency are no substitutes for the less glamorous, painstaking but in the long-term more rewarding political course to revolutionary regroupment and workers unity.

Trotskyism and Sexual Politics

By Martin Cook

Introduction

The following article on Trotskyism and Sexual Politics needs to be placed in the context of a general reappraisal of the Trotskyist heritage and tradition, from which Socialist Charter, like many other tendencies, originated. It has become increasingly clear that the irrelevance and splintering of the Fourth International after Trotsky was not merely the fault of its poor leadership, but was linked to basic inadequacies in the body of political ideas it inherited from Russian Bolshevism and the Comintern. One of the most glaring gaps was the sex- pol field, and we feel this is linked to a tendency towards ‘economic determinism’ and ‘mechanical materialism’ among orthodox Marxists for the last 100 years; that is, an assumption that the workers of the world would be impelled towards socialist conclusions by ‘objective’ economic forces, and that ideological and ‘subjective’ factors would not play a major independent role.

This, of course, has multiple implications for the time- honoured Trotskyist analyses of reformism, Stalinism, the revolutionary party, and so on. Unlike those who would see comrades such as Lenin and Trotsky as infallible sources of authority who solved every important question once and for all, we regard them as great revolutionaries who made imperishable contributions in the fight against the orthodoxies of their own time, but nonetheless were limited by their historical situation. So to adopt a critical attitude towards them does not signify a rejection of their important gains for our movement or a smug attempt to show how ‘clever’ we are, but a break from the attitudes of religious cultism, and an honest attempt to go forward rather than jealously guarding past errors in a fossilized form.

Recently, serious critiques of Trotskyism have emerged from comrades in the Labour Party (e.g. Geoff Hodgson, Peter Jenkins), the Communist Party of Great Britain, and Big Flame. While we would hardly go along with all their views, many of their points certainly hit home. Most Trotskyists— even those most in contact with the real world—have great difficulty in making a credible response to these arguments, given their proclivity to fall back defensively on such shibboleths as the ‘crisis of leadership’ as described in the 1938 Transitional Programme, The Death Agony of Capitalism and the Tasks of the Fourth International. The essentials of revolutionary socialist politics do need to be defended—but by critically applying them to changing conditions, and not sterile orthodox dogmatism.

In the field of sexual politics it is noteworthy with what suspicion feminists and gay liberationists in Britain (no dour: elsewhere as well) regard the activities of the Trotskyist group; as arrogant, manipulative, sectarian, in fact uninterested in their own concerns. This has led, for instance, to the banning of organizationally affiliated women from some socialist feminist meetings. On the other hand there are healthy signs in parts of the far left of a new readiness to take up serious debate with both socialist feminists and radical feminists in the women’s liberation movement (WLM). We have no doubt that revolutionary Marxists will have important contributions to make to the debates in the women’s movement, but only if they can first set their own house in order First and foremost, this will necessitate a sharp break from accepted Trotskyist views on women’s oppression and how to fight it.

The orthodox tradition

“Opportunist organizations by their very nature concentrate their chief attention on the top layers of the working class and therefore ignore both the youth and the woman worker. The decay of capitalism, however, deals its heaviest blows to the woman as a wage earner and as a housewife. The sections of the Fourth International should seek bases of support among the most exploited layers of the working class, consequently among the women workers. Here they will find inexhaustible stores of devotion, selflessness and readiness to sacrifice.”[1] The above well-known passage, the only reference to the ‘Woman Question’ in the Transitional Programme of the Fourth International, is far from being an isolated case. We can say, I think, that the absence of serious consideration of sexual politics is the most outstanding lacuna in the whole of the Lenin-Trotsky tradition. The contributions of communists such as Alexandra Kollontai and Wilhelm Reich have never been regarded as part of the ‘authorized canon’ or the ‘codifications’ of the movement—till recently they have hardly even been discussed. Sex-pol has simply not been recognised as a valid and distinct dimension of revolutionary praxis, as opposed to economic wage-exploitation pure and simple. It is all very well to mock the ‘orthodox’ of the Militant tendency or the WRP for their philistine contempt for the oppression of women as a sex, but they are only being consistent and loyal to their traditions. The views of the more sophisticated tendencies implicitly lead to similar conclusions, as we shall see.

It is not that comrades such as VI Lenin failed to recognise formally the existence of the special oppression of women:

.. we are aware of these needs and of the oppression of women, that we are conscious of the privileged position of the men, and that we hate—yes, hate—and want to remove whatever oppresses and harasses the working woman, the wife of the worker, the peasant woman ... and even in many respects the woman of the propertied classes.”[2]

Nor was Lenin adverse to movements of working women as well as a communist women’s movement:

“The party must have organs—working groups, commissions, committees, sections or whatever else they may be called— with the specific purpose of rousing the broad masses of women, bringing them into contact with the party and keeping them under its influence. This naturally requires that we carry on systematic work among the women.”[3]

The problem is that the aim of communist ‘women’s work’ was seen in a one-way fashion as winning women to the party —not necessarily as learning anything politically from women’s movements (we must note that there was a much sharper divide between socialist women’s organizations and liberal bourgeois ones than exists today). More fundamentally, Lenin tends to see the main problems as (a) winning legal and political equality and (b) fighting economic and social exploitation and drudgery. Matters concerning sexual liberation or the ‘politics of the personal’ are clearly regarded as peripheral at best—not to say diversionary.

This becomes appallingly obvious when we encounter Lenin’s views on the contemporary exponents of ‘sex-pol’ within the Third International. (These quotes are taken largely from Clara Zetkin’s reminiscences rather than actual ‘scripture’—however, there seems no obvious reason why she should have wanted to distort his sentiments.):

“I have been told that at the evenings arranged for reading and discussion with working women, sex and marriage problems come first ... I could not believe my ears when I heard that... Freud’s theory has now become a fad! I mistrust sex theories expounded in articles, treatises, pamphlets, etc.—in short, the theories dealt with in that specific literature which sprouts so luxuriantly on the dung heap of bourgeois society.”[4]

“This nonsense is especially dangerous and damaging to the youth movement. It can easily lead to sexual excesses, to overstimulation of sex life and to wasted health and strength of young people.”[5]

“Promiscuity in sexual matters is bourgeois. It is a sign of degeneration. The proletariat is a rising class. It does not need an intoxicant to stupefy or stimulate it, neither the intoxicant of sexual laxity or of alcohol.”[6]

And the solution?

“Young people are particularly in need of joy and strength. Healthy sports, such as gymnastics, swimming, hiking, physical exercises of every description ... This will be far more useful than endless lectures and discussions on sex problems and the so-called living by one’s nature. Mens sana in corpore sano”[7]

Similar ideas were expressed in letters to Inessa Armand (written in 1915, not at a time of revolutionary crisis which might have been more ‘excusable’). He criticised the demand for ‘free love’ in her proposed pamphlet as being liable to be misconstrued as the ‘bourgeois’ desires for freedom from childbirth and ‘freedom to commit adultery, etc.’ (horrors!)[8]

One could have quoted at greater length these reactionary and philistine views. The aim is not, in fact, to heap mockery on Lenin and detract from his inspiring overall revolutionary record. It is not surprising, in the circumstances of the early twentieth century, that such notions should have been widespread not merely in society generally but in the revolutionary movement itself. What matters is to what extent they were combatted.

Certainly by Kollontai for a time, and no doubt others. But not within the mainstream Trotskyist movement, far from it. (Kollontai’s works have only recently been reprinted, as often I think by feminists as by Leninist/Trotskyist organizations.) The failure to do this most be partially ascribed to the failure of the Third and Fourth Internationals to break conclusively with the economic determinism (‘mechanical materialism’) of the classic Second International. Thus the oppression of women could be explained as flowing from feudal survivals and economic backwardness:

“The electric lighting and heating of every home will relieve millions of ‘domestic slaves’ of the need to spend three — fourths of their lives in smelly kitchens.”[9]