Janet Biehl

Ecology or Catastrophe

The Life of Murray Bookchin

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

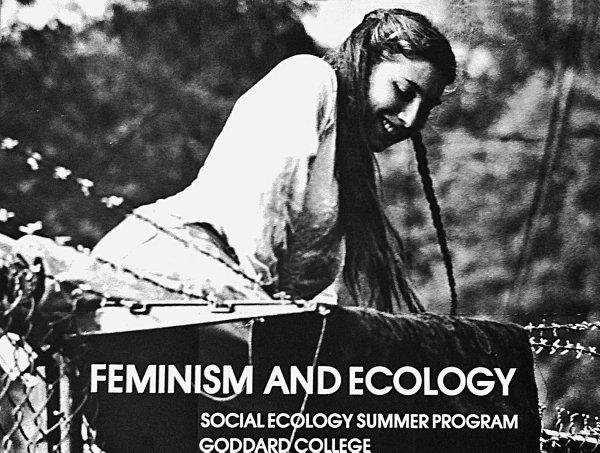

Ecology or Catastrophe

THE LIFE OF MURRAY BOOKCHIN

Janet Biehl

[Copyright]

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

© Janet Biehl 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Biehl, Janet, 1953–

Ecology or catastrophe : the life of Murray Bookchin / Janet Biehl.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978–0–19–934248–8 (alk. paper)

eISBN 978–0–19–934250–1

1. Bookchin, Murray, 1921–2006. 2. Ecologists—United States—Biography. 3. Environmentalists—United States—Biography. 4. Social ecology—United States. 5. Environmentalism—United States. I. Title.

GF16.B66B54 2014

363.7092—dc23

[B]

2013029714

Acknowledgments

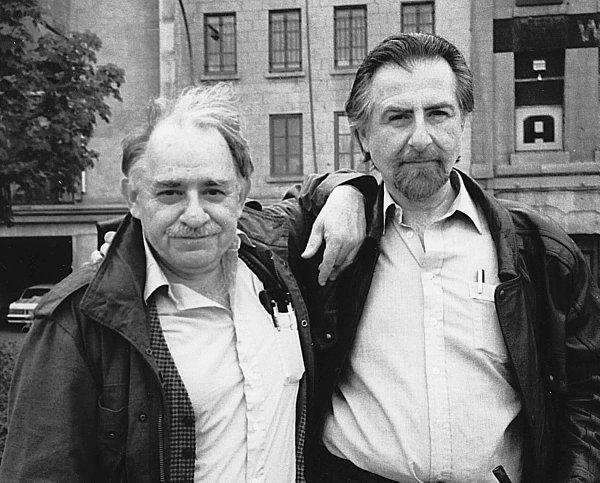

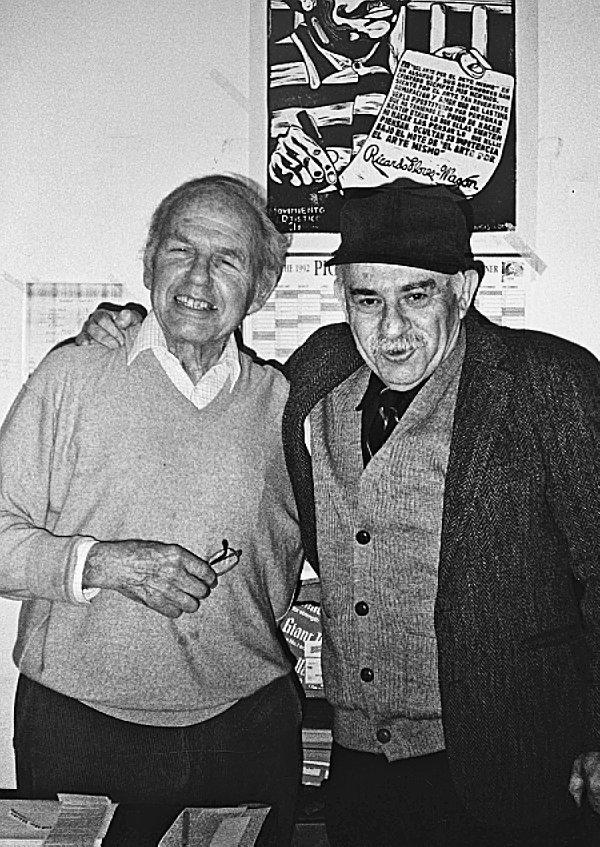

I MET MURRAY late in his life, in 1987, and as I did the research for this book, I was fortunate that many who knew him well before I did gave generously of their time and their thoughts. I could not have written it without extensive interviews from Dan Chodorkoff, Barry Costa-Pierce, Bob D’Attilio, the late Dave Eisen, Joy Gardner, David Goodway, Jack Grossman, Wayne Hayes, Howie Hawkins, Joseph Kiefer, Ben Morea, Jim Morley, Calley O’Neill, Charles Radcliffe, Dimitri Roussopoulos, Karl-Ludwig Schibel, and Brian Tokar. In some cases they shared papers, books, and tapes as well as their impressions and memories. I’m deeply grateful to all of them.

Heartfelt thanks to others who talked to me about Murray as well and sometimes also shared documents: Flavia Alaya, Steve Baer, Harriet Barlow, the late Peter Berg, David Block, Reni Bob, Horst Brand, Stewart Brand, Frank Bryan, Caitlin Casey, Juan Diego Pérez Cebada, Stuart Christie, Linda Cohen, Jutta Ditfurth, David Dobereiner, Crescent Dragonwagon, Mike Edelstein, Fanis Efthymiadis, Bob Erler, Paolo Finzi, Gil Friend, Carlos “Chino” Garcia, Vincent Gerber, Rafa Grinfeld, Richard Grossman, Susan Harding, Anne Harper, Wolfgang Haug, James Herod, Annette Jacobson, Robert Kadar, Jerry Kaplan, Stavros Karageorgakis, Ken Knabb, Bill Koehnlein, Makis Korakianitis, Lucia Kowaluk, Burton Lasky, Ursula K. Le Guin, Sveinung Legard, John Lepper, Mat Little, Arthur Lothstein, Sam Love, Svante Malmström, Vivien Marx, Lisa Max, Lester Mazor, John McHale, Paul McIsaac, John McMillian, Richard Merrill, Stephanie Mills, Roy Morison, Brian Morris, David Morris, Pat Murtagh, Osha (formerly Tom) Neumann, Roz Payne, Ivar Petterson, Paul Prensky, Peter Prontzos, Michalis Protopsaltis, Michael Riordan, Mark Roseland, Meg Seaker, Rick Sharp, Josh Shortlidge, Chuck Stead, Suzanne Stritzler, James Swan, Jane Thiebaud, and Bruce Wilson.

In the early 2000s Bookchin donated his papers to the Tamiment Library at New York University. Before he did so, I made photocopies of many of them; hence the allusions to “MBPTL and author’s collection” in my source notes. The originals are at Tamiment; I am extremely grateful to Peter Filardo and Erika Gottfried for help in accessing those materials. After this manuscript was completed, I turned my own collection over to the International Institute for Social History in Amsterdam, for the convenience of scholars in Europe. I’m grateful to Huub Sanders of the IISH for arranging for that deposit.

I’m also most grateful to the Anarchist Archives Project in Cambridge, Massachusetts; the Institute for Social Ecology archive in Marshfield, Vermont; the Fletcher Free Library in Burlington, Vermont; the Bailey-Howe Library’s Special Collections, at the University of Vermont in Burlington; the Goddard College Archives in Plainfield; the Vermont Historical Society in Montpelier; the Vermont State Archives and Records Administration in Waterbury; Milne Special Collections at the University of New Hampshire, in Durham; and the Centro Studi Libertari in Milan, Italy.

For their hospitality on my research trips, I thank Inara De Leon and Todd Norbitz, Tim and Berle Driscoll, Dave and Shirley Eisen, David Goodway and Che Mah, and Stephen Kurman. Inara De Leon, Laura Ramirez, and Andy Price gave me early encouragement. K. K. Wilder and Ted Tedford’s tips on interviewing proved helpful, and my writing benefited greatly from conversations with Paula Harrington and Eve Thorsen. Judith Jones, in retirement after her remarkable decades-long editing career at Knopf, read and commented helpfully on the manuscript, as did Stavros Karageorgakis and Karl-Ludwig Schibel. Any errors in the book are my own responsibility.

For their emotional support during my work, I’m indebted to Bronwyn Dunne, Eirik Eiglad, and Eve Thorsen—you were indispensable to this project, my dear friends. Thanks as well to Sezgin Ata, Emet Degermenci, Metin Guven, Marcus Melder, Peter Munsterman, Michael Speidel, and Thodoris Velissaris for their encouragement; to Mary Biehl and Bea Larsen for cheering me on; and to Lynn Brelsford for keeping my spirits up in the home stretch.

Heartfelt thanks as well to Drs. Claudia Berger, Zail Berry, and Matthew Watkins, as well as the Visiting Nurses Association of Chittenden County, for the superb end-of-life care that they provided for Murray. Special thanks to William E. Drislane, Esq.

For her persistence in finding my book an excellent home, hearty thanks to my agent, Anne G. Devlin. It is a great privilege to be published by Oxford University Press. My editor, Jeremy Lewis, stood by my book through thick and thin, for which I’m immensely grateful.

I’m grateful above all to Murray for all he gave me, and to the improbable twist of fate, indeed the astounding good fortune, that brought his life and mine together.

Prologue

THE KEYNOTE SPEAKER, said to be a leading figure in the ecology movement, waited beside the stage. I’d expected to see an aging hippie, that day in 1986. Yes, aging he was, with a shaggy gray mustache and a certain weariness in his sixty-something frame. But his clothes were hardly hippie style—they were industrial dark green, like a polyester uniform, and his shirt pocket was stuffed with mechanical pencils that skewed the suspenders and his houndstooth wool vest.

“He was a Communist as a boy, you know,” a woman sitting next to me remarks. I eavesdrop: “Yes, but he’s been writing on ecology since before I was born,” says her friend.

As the audience settles, the student organizer steps to the podium. Tonight’s speaker, he explains, has been writing about environmental issues since the 1950s. His book Our Synthetic Environment raised the alarm about pesticides and industrial agriculture, soil depletion, air and water pollution, deforestation, and nuclear power—and it was published in the spring of 1962, a few months before Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. In his next book, Crisis in Our Cities, he actually warned about global warming and said that to avoid ecological catastrophe, we’d have to wean ourselves from fossil fuels and learn to use renewable energy, as well as eat locally and farm organically.

He was the founder of radical ecology—not of environmentalism, and surely not of conservationism, but ecology as a radical social and political issue.

The student organizer makes the introduction: “Please welcome … Murray Bookchin!”

He moves with arthritic deliberation to the podium. Grasping it by the edges, he surveys the crowded with large smoldering eyes.

“My friends,” he begins in a rumbling New York accent, “the power of capitalism to destroy is unprecedented in human history. It is on a collision course with the environment, threatening our air and water, flora and fauna, the natural cycles on which all life depends. It is destroying diversity, simplifying the natural world, turning forests into deserts, soil into sand, and water to sewage. It’s pushing back the clock, undoing countless millennia of biotic evolution.”[1]

His craggy countenance comes to life as he continues, his words falling into the rhythm of a street orator. His formidable eyebrows quiver like those of the old 1930s labor leader John L. Lewis, who, I would later learn, he much admired.

“It’s not only threatening the integrity of life of earth, it’s turning us into commodities. It invades us with advertising, making us think we need things that are actually useless. It’s simplifying our social relationships, defining us as buyers and sellers. It’s turning our neighborhoods and communities over to the cash nexus, bringing them into the ever-expanding market.”

If you listen closely to his baritone cadences, you can hear traces of Russian folksongs and Old Testament prophecy, of Old Left agitprop and the snarky defiance of a Dead End Kid.

“Either we’re going to let the grow-or-die market economy massively destroy the planet”—his hands slice the air—“or we will have to make a sweeping reconstruction of society. If we’re going live in harmony with the natural world, we will have to change the social world.

“In earlier times society was more communal and small scale—people took responsibility for each other, and for themselves, and had the confidence to stand up for themselves. I’m not saying we should go back in time. But we can learn from some of the old ways. About interdependence, about cooperation and mutual aid.”

He is bubbling and rattling like a samovar on the boil.

“We have to organize a movement to create an ecological society, one that’s decentralized, democratic, humane. We have to start revitalizing our communities and our neighborhoods, creating a new politics at the local level, bringing them back to life, strengthening them.”

It isn’t just a speech—it’s a performance, inspiring his listeners to take action.

“My critics will tell you that I’m a wild-eyed utopian. But I assure you everything I’m suggesting is immensely realistic. The more we try, on the basis of so-called pragmatic considerations, to change society in a small piecemeal way, the more we lose sight of the larger picture. The real pragmatic solution is the long-range one—the one that gets down to the root causes of the ecological crisis.”

By now the audience is leaning forward in their seats. “My friends, either we will create an ecotopia based on ecological principles, or we will simply go under as a species. We have to be realistic and do the impossible—because otherwise we will have the unthinkable!”

* * *

The man I met in 1986 believed that ideas can move history forward, that if you come up with a good social-political idea, then people will recognize its rightness and help you try to put it into effect.

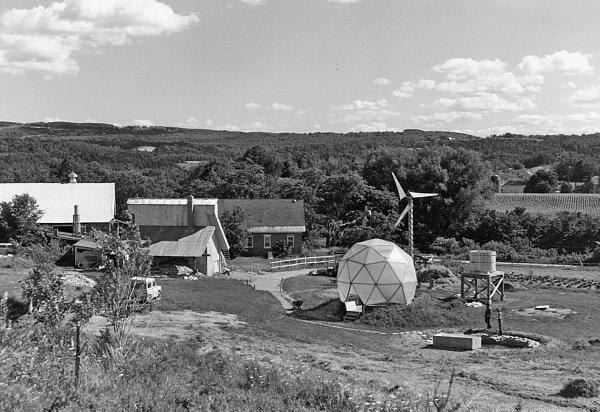

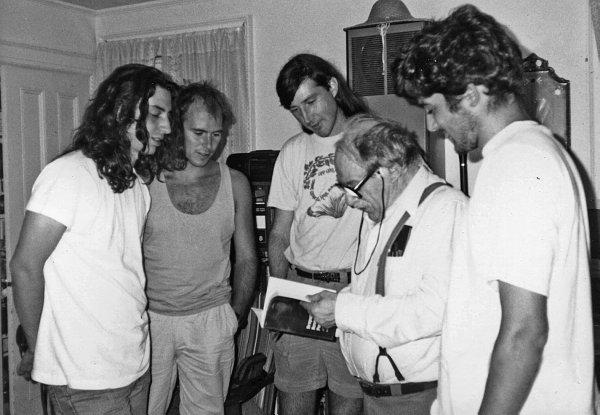

That belief came from his childhood in the Communist children’s movement, and it stayed with him for the rest of his lifelong journey through the American Left. It stayed with him after he gave up on Marx and became the most important anarchist thinker in the second half of the twentieth century. It stayed with him as he realized that the growing environmental crisis had profound implications for human social organization itself. It stayed with him as he explored the terrain between utopia and reality and found there a vision of a rational, ecological society. It stayed with him as he became a mentor to the counterculture in the 1960s. It stayed with him in the early 1970s, when he founded a school in Vermont that taught students how to farm organically, make solar and wind installations, and create urban gardens. It stayed with him as he helped build the antinuclear movement in the 1970s and the Green parties of the 1980s, calling for face-to-face democracy based on citizens’ assemblies, like the town meetings of his adopted state.

He was a genuine political and intellectual independent, living outside the usual spectrum of life choices. Fired with a sense of urgency to spread the message that the ecological crisis required a profound rethinking, he subordinated his personal aims to the larger cause until they merged. He refused to yield to despair, holding firm to his belief that struggling to create the new society would bring to the fore people’s potentialities for ethical behavior, a rational outlook, and social cooperation.

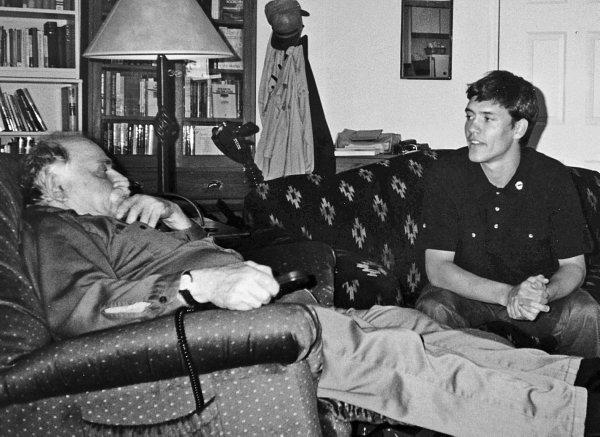

Yet he was also ebullient and charming. By lucky happenstance, I met him at a good moment and joined his cause for the last nineteen years of his life, as we collaborated, writing and traveling together. The Communists might have taught him to be combative, but I found that he had an open, guileless, and generous heart.

We agreed that I would one day write his biography. I interviewed him formally a few times, but more often he told me stories about his life, over the kitchen table or in the wee hours. The line between interview and conversation blurred. The stories I absorbed became second nature to me and now form the architecture of this biography.[2]

After he died, a pauper at eighty-five, I tried to keep him in my life for at least another few years by writing his biography, making up for his absence by researching his life, filling in the gaps between those stories, interviewing people who had known him, and studying the movements in which he’d worked. Where people’s memories were contradicted by a document, I chose to follow the written record. Similarly, rather than rely entirely on my own memory of his stories, where possible I’ve cited a written or published source.

Finally I was able to reconstruct his trajectory moving forward in time, and in so doing I discovered its logic and integrity. I make no claim to have written a full flesh-and-bones biography; it is rather a political biography, of a thoroughgoing zoon politikon, a man formed by the political actors he knew, by the close-knit political groups to which he belonged, by the broader movements to which he adhered, and by the times in which he lived.

Over the decades Murray himself influenced many people, but to trace that influence, to identify even a fraction of those who felt their lives changed by him, would be beyond the scope of this biography. Rather, I focus on those who influenced him: who altered his way of thinking in some substantive way, or made a concerted effort to put his theoretical ideas into practice. Although an energetic public speaker, he preferred working intimately with small groups of dedicated, educated comrades; above all, he needed them to be writers, able and willing to enter the public sphere with him, at the very least in the periodicals that his various political groups issued. The secondary figures whom I spotlight, then, are those whose work with him is evident in their paper trails.[3]

It’s easy to dismiss him as a utopian, but he made a compelling case that utopia has actually become necessary for the continuation of life on earth. The crisis of climate change that we face today is unprecedented, and his framework may yet prove to be the one that we need not only to sustain but also to advance life on earth.

1. Young Bolshevik

IN OCTOBER 1913 Murray Bookchin’s maternal grandmother Zeitel stepped off the SS Rotterdam in New York and, with her two children, passed through Ellis Island. Up to now, the tall, stern, steely-eyed woman had spent her life trying to overthrow Russian tsardom. Now she was coming to America, to battle tyranny in a new land.

Born in the Russian Pale in the early 1860s, Zeitel Carlat had received an unusual secular, liberal education as part of the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment. Studying science and mathematics and literature, she had learned to reject traditional religion and to dress in modern clothing. She even disdained the Yiddish language in favor of Russian, the ecumenical language, the tongue of Pushkin and Nekrasov. Her cousin Moishe Kalusky was another child of the Haskalah—he cut his hair, modern style, after which his parents said Kaddish for him.[4]

At the time Zeitel and Moishe were born, Tsar Alexander II (“the kindliest prince who ever ruled Russia,” Disraeli called him) had emancipated the serfs and instituted a liberalizing reign—he even eased some of the restrictions on Jews, opening the doors of universities to a small quota. Growing up in those forward-looking times, Zeitel and Moishe felt that they were witnessing the dawn of a new era, in which the Russian people would finally achieve emancipation. Young intellectuals, they read Alexander Herzen and Nikolai Chernyshevsky and became narodovoltsy, or revolutionary populists. They dreamed that Russian peasantry would mount an uprising that would spark a revolution to sweep away Russia’s oppressive ruling structure and undertake a chernyi peredel, or “black redistribution,” of land. Then Russia could become a socialistic society based on the traditional peasant obshchina, or village commune, in which land would be held by all cooperatively.

Zeitel particularly admired Chernyshevsky’s 1863 novel What Is to Be Done?, a handbook for her generation of radicals. It depicts young Russians—especially women—participating in the communal lifestyles of an emancipated society. To the end of her life, Zeitel would keep a portrait of its author on her wall.

By 1881, some narodovoltsy felt that the peasant uprising was too slow in coming. In March a group of them decided to spark it themselves: they assassinated the tsar-liberator, Alexander II. But instead of bringing on the long-awaited revolutionary upheaval, this terrorist act brought Russia’s liberalizing process to a screeching halt. The empire’s wrath thundered down on the Jews, blaming them as a people for the murder. Incensed Russians carried out pogroms in the shtetls. The successor tsar, Alexander III, slammed shut the doors to Jewish education and entry into professions and issued repressive decrees that made life intolerable. Jews began emigrating to the West en masse.

The most ardent Jewish revolutionary populists, however, were unfazed by the pogroms, regarding themselves as human beings and Russians more than as Jews and determined to continue the fight for a humane, socialist Russia, even against the new wave of repression. When the tsar’s secret police, the okhrana, crushed their groups in Moscow and St. Petersburg, they simply moved to the provinces. In the 1880s, southwestern Russia became a revolutionary hotbed, churning out reams of radical literature. By the 1890s, Zeitel and Moishe—now married—were living there, at the edge of the Russian empire, in the small city of Yednitz, just across the Prut River from Romania.[5] Revolutionaries who were being pursued by the okhrana could make their way to Yednitz, where Zeitel and Moishe would help them cross the river, silently, on moonless nights. Sometimes Zeitel would cross the river herself and bring back literature and exiled agitators.[6]

Their home became a hub of socialist intellectual and political activity. Young revolutionaries came there for advice and education. They would meet at night, by candlelight or kerosene lamps, in forested areas, even cemeteries, to discuss political developments and develop strategies. In 1902 Zeitel and Moishe joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party, the latest incarnation of Russian populism, this one infused with Marxist ideas to attract the growing population of urban workers as well as the peasantry. In 1905 the urban workforce mounted a series of strikes and mutinies that constituted an incipient revolution against tsarist absolutism. To aid the movement, Zeitel ran guns across the border, stashing them in hiding places where comrades could stealthily retrieve them for good use.

But the 1905 revolution was crushed, and soon afterward Moishe died of bladder cancer. Zeitel was left with their two children, Rose or Rachel (who had been born in 1894) and Dan (born a year later).[7] She hoped to mold her offspring into disciplined, self-sacrificing revolutionaries like herself, but alas, neither of them had inherited her temperament, her ability to defer gratification indefinitely for the sake of a great purpose. In fact, her high-spirited daughter Rose tried to run off to the nearby Gypsy camp—Zeitel had to drag her back home. Chubby, impulsive Rose had somehow inherited none of the mother’s sharp edges; and where Zeitel’s eyes were gray and austere, Rose’s were brown and expressive, even dreamy.

Sometime in 1912 or 1913, the tsarist police raided their home. In the summer of 1913, Zeitel packed up her family and crossed the Prut River for the last time. Making their way northward to the Netherlands, they boarded the Rotterdam and sailed for New York.[8]

A decade earlier, the US Congress had barred immigration by anarchists. Zeitel might well have been denied entry. But she managed to get through with her teenage children. Border crossings, after all, were her specialty.

Zeitel rented a room in a squalid tenement on the Lower East Side, already packed with immigrant Jews, and found work for herself and her children in the needle trades. The neighborhood and its surroundings seethed with labor unrest. Public meetings abounded—the “greenhorns” likely heard the anarchist Emma Goldman stand and inveigh against the ruling class and the state, and the socialist Eugene V. Debs demand the emancipation of the working class.

Even in this radical milieu, Zeitel was contemptuous of the new country, with its frantic pace and crass materialism. Russian culture and lifeways were far superior to these boorish American ones, she believed, and its radical tradition immensely more advanced. The astonishing events of 1917 only proved her case. In February, strikes and demonstrations in Petrograd (formerly St. Petersburg) led to the abdication of the hated tsar and the end of the Romanov dynasty. A provisional government took power, while the city of Petrograd was governed by a workers’ council or soviet. Then in November, a group of disciplined Marxist revolutionaries—Bolsheviks—stormed the Winter Palace, toppled the provisional government, and proclaimed a working-class state. In the old country, socialism was finally at hand.

Zeitel and her family rejoiced, as did radicals all over the world, be they socialist or anarchist. In solidarity, Communist parties were formed in many countries, including the United States. The Kaluskys did not join the American Communist Party—rather, following their populist roots, they joined the anarchistic Union of Russian Workers.[9] Rose, now a young milliner, joined the Wobblies, or the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

While attending a summer camp for Communist youth, she met Nathan Bookchin, a fellow Russian Jewish immigrant, two years younger than she. With Nathan, she could speak Russian; together they could wax nostalgic about their homeland and euphoric about its world-shaking revolution. Perhaps she was wearing one of her Russian blouses the day he proposed marriage and she accepted. Her domineering mother didn’t like the young man, but despite Zeitel’s disapproval—or perhaps because of it—Rose and Nathan married.

Around 1920, the family moved north to the fresher air of the Bronx, whose new IRT subway line, the Third Avenue El, would allow them to commute to work in Manhattan’s garment district each day. Newlywed Rose and Nathan moved into a railroad flat on the ground floor at 1843 Crotona Avenue, in East Tremont, while Zeitel and Dan rented an apartment nearby. East Tremont felt comfortably Russian to them, an ethnic Jewish village laced with Old World traditions.[10] But it also had a radical ambience—Workmen’s Circle clubs, union locals, and socialist meeting halls were more numerous and influential in that neighborhood than synagogues. Shops were family owned: the kosher butcher, the greengrocer, the cigar maker, and more.

Rose gave birth to Murray, her first and only child, on January 14, 1921.[11] In keeping with the family’s secular, Haskalah tradition, they would give him no Jewish education. He would not be bar mitzvahed. They would observe no religious holidays or rituals. Nor would they make any effort to Americanize him.

Instead, they raised him as a little Russian boy. For his first two years, Rose—who resisted learning English and would never even take US citizenship—spoke to him only in Russian, sang Russian songs to him, and much to his embarrassment, clothed him in Russian dress. His earliest memories were of her playing Glinka on the piano, wearing a Russian blouse. In the evenings, the family would go to Crotona Park to listen to Goldman’s brass band play Rachmaninov.

But the Bookchin-Kalusky marriage was troubled. Zeitel’s dislike of Nathan evolved into outright hostility. Her animus was well founded—her son-in-law bullied Rose (as Murray would later tell me), beating her when she displeased him and striking his son as well. Finally, when Murray was five or six, Nathan abandoned the family altogether.[12]

Unruly Rose, inexperienced with motherhood, had limited childrearing abilities. Even a child with a placid temperament might have taxed her, but this high-spirited son was more than she could handle alone. Zeitel probably didn’t have to be asked twice for help—she moved into the Crotona Avenue apartment, bringing Rose’s brother Dan with her.

Zeitel hung her old pictures of Chernyshevsky and Herzen and Tolstoy on the walls and arranged her leather-bound Russian books on the shelves. She suffered, it was understood, from a “weak heart,” but she scrubbed and tidied the disheveled apartment energetically nonetheless. She still stood dignified and straight-backed behind her pince-nez. She still possessed that stern revolutionary will.

And she perceived Murray’s bright, inquiring mind: here, finally, was the child she could imbue with her own political passion. She taught her grandson, first, what she had learned in school: that all religion is mere superstition. Then she taught him about the Russian revolutionary tradition, going back to Stenka Razin and Emilian Pugachev, those old Cossack firebrands, dazzling his mind with tales of their seventeenth- and eighteenth-century insurrections against despotism—he knew and loved their names and exploits before he’d even heard of Robin Hood. She taught him about populism and the chernyi peredel, the black redistribution, and about her own life as a Socialist Revolutionary, and about gun-running and secret strategy sessions in the dark of night.

“Basically,” he would tell me, “my family educated me in revolution,” especially the greatest revolution in history. Together Zeitel and Murray gazed at picture books of Bolsheviks marching and conferring and orating. Before young Murray knew who Washington and Lincoln were, he was familiar with Lenin, as well as the German revolutionary leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. He especially admired the dashing Leon Trotsky, who had engineered the Bolshevik takeover, then organized the Red Army, personally commanded it on horseback from the front lines, and led it to stunning victories over the White forces of reaction.

Murray revered his grandmother, who was strict and strong but also warm and loving to him. He shared a bedroom with her, sleeping on a cot next to her bed. On an August night in 1927, they heard newspaper boys running along Crotona Avenue shouting out the terrible news that Sacco and Vanzetti had been electrocuted. The state of Massachusetts had tried and convicted the two Italian immigrant anarchists for murdering a bank official. Their trial had been blatantly unfair—the judge who sentenced them to death had boasted of getting rid of “those anarchist bastards.”[13] Now they had been executed. Zeitel rushed outside to get a newspaper, finding their neighbors on the street weeping. When she returned to the flat, she held up the front page—it had a drawing of the two men in the electric chair—for her grandson as if to brand it in his mind. This is what capitalism does to working people, she told him. Don’t ever forget.[14]

By now, other Kalusky family members had immigrated to New York, and on weekends the railroad flat would often be filled with relatives, drinking tea together from a samovar, sipping it from saucers, the Russian way, through sugar cubes held between their teeth. They played Russian music on an accordion or piano and sang songs like the stirring “Whirlwinds of Danger” (“March, march ye toilers, and the world shall be free”) and the melancholy strains of “Stenka Razin.”

They talked incessantly of politics: about the death of Lenin in 1924 and the rise of Stalin to the revolutionary helm. Doubtless they were stunned to learn in 1927 that Stalin had sent Trotsky into internal exile, condemned for betraying the revolution. They must have shaken their heads in disbelief: could the Red Army commander really be guilty of such a thing?

As much as they were transplanted Russians, however, they could not prevent Murray from becoming American. When he stepped out the door of the railroad flat, he secretly changed out of the Russian clothes that his mother made him wear and put on knickers: he tossed aside the hated Russian hat and put on a snap cap, turning it sideways for panache. Then he could join his friends to play stickball in the shadow of the Third Avenue El or play-act Al Capone stories in alleys and fire escapes and roofs, with water pistols and BB guns.

As he got older, school was the last place he wanted to be. “My truancy was scandalous,” he told me. He and a friend much preferred to head west to the Hudson, cross the spanking-new George Washington Bridge, and explore the Palisades. Or they’d go north to the Italian neighborhood, above 182nd Street, where people had gardens and goats. Beyond lay forests and grasslands and farms. Sometimes the farmers brought their produce into his neighborhood, rather like today’s farmers’ markets.[15]

* * *

One night in May 1930, nine-year-old Murray stretched out on his cot while Zeitel lay reading a volume of her beloved Gorky. Suddenly her book dropped to the floor. When the boy peered over, he found her dead from a heart attack.

Losing her was devastating. She had been his only competent, attentive parent. Childlike Rose, too, had been psychologically dependent on her dominating mother—in fact, without her, she would not do well. Too often she would try to escape from her responsibilities into the fantasy world of the local movie theater, much as she had once tried to run off to the Gypsies. “Instead of raising me,” Murray told me, “she took me to movies.”

The personal crisis of losing his grandmother coincided, it so happened, with a social crisis: the onset of the Great Depression. The stock market crashed in October 1929, leading to bank closings and factory shutdowns. Rose lost her millinery job. She and Murray now had only Nathan’s paltry alimony payments to live on—and she spent them mostly on clothes at Klein’s in Union Square or on Orchard Street.

She bullied her son, slapping him for trivial offenses. Once when she raised her hand to hit him yet again, he grabbed his BB gun and fired at her posterior, grazing it—and warned her never to strike him again. Thereafter the two merely coexisted. At the age of nine, he was all but orphaned.

A few months after Zeitel’s death, the doorbell rang, and Murray opened the door to find a boy about two years older than he, hawking a children’s magazine called New Pioneer. He held up a copy for Murray. “It tells young people the truth about what’s going on in America … that Washington was a drunkard, and Jefferson owned slaves.”[16] Murray gave him a few coins and then curled up with the magazine, reading it from cover to cover. It explained that American democracy was a hoax, and that the rich called the shots. A handful of millionaires of “tremendous wealth—Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, the Goulds—owned the American economy,” it explained, “while workers were paid only ten to twenty dollars a week.” But in the Soviet Union, the story was very different: there workers were “pioneering in a new world,” creating a socialist paradise. Wouldn’t it be fine, New Pioneer urged its young readers, if American workers would “follow in the footsteps of the workers of the Soviet Union!” Fortunately, the Communist Party was ready to lead them.[17]

The magazine-selling boy had told Murray about a group called the Young Pioneers of America that talked about these ideas at regular weekly meetings, and had invited him to the next one. The following night Murray went over to the International Workers Order building on East 180th Street, dashed up the creaky staircase, opened a door—and entered the international Communist movement. The Young Pioneers were the Communist children’s section, for those nine to fourteen years old. Perhaps a dozen boys were arrayed behind desks. A few teenagers were standing by, but the children ran the meeting as much as possible.[18]

Comrades and fellow workers! shouted a boy at the front. This meeting of the Young Pioneers will come to order! The first part of the meeting, Murray came to understand, would always be educational. The Pioneers would talk about the glorious Soviet Union, or the economic crisis underway in the United States, or cases of injustice like the Scottsboro Boys; or they would analyze popular culture, pointing out the racism in movies like Tarzan the Ape Man.

In the latter half of the meeting, the Pioneers would do something practical, like make signs and banners for a demonstration. And at the meeting’s close, they would sing “The Internationale.” When they came to the last, rousing chorus (“’Tis the final conflict”), they would raise their right hand and hold it with the palm to their temple in a five-finger salute, to symbolize the five-sixths of the world’s landmass that socialism had not yet conquered. Not yet.

The Communists rescued Murray from his personal crisis by becoming his surrogate parents. “It was the Communist movement that truly raised me,” he would recall, “and frankly they were amazingly thorough.” And they continued Zeitel’s training regimen: where she had groomed him to become a Russian revolutionary, they would mold him into a leader of the future proletarian revolution in America—a young commissar. And even as they educated him, they provided him with stability and validation. They taught him to subsume his personal distress into an intense devotion to the Communist Party, the Soviet Union, and the coming revolution. They gave him brothers and sisters—his branch comrades—as well as an extended family in the movement’s many other branches. The Communist movement became, in effect, his home.[19]

They taught him about Lenin, who had shown the Russian workers “how to organize against their oppressors, how to fight for their rights,” then had led them in revolution. They taught him about Rosa Luxemburg, that “flaming symbol of revolutionary courage and devotion to the working class,” who had tried to spark an insurrection to create a Soviet Republic in Germany.[20]

But to the fatherless, grandmotherless boy, the persona of Karl Marx, as presented by the Pioneers, must have been irresistible. “There was no one jollier or merrier” than Marx, New Pioneer explained. “His eyes twinkled at a good joke or a quick answer,” and “when he laughed, it was with a hearty roar which shook him all over.” He had been a loving father, and his home in London “was always the meeting place for revolutionists of many countries”—just as Zeitel’s had been, back in Russia.[21]

At one meeting, the Young Pioneers were shown a Soviet propaganda movie, The Road to Life. Set in 1923, it portrayed the lives of children left orphaned and homeless by the Russian civil war. A group of these children (there were actually thousands) survive by roaming the countryside and robbing people. Soviet police round up the young bandits and bring them to a containment center, from which they will be sent to a reformatory. But just in time a kindly social worker realizes that they can have a better fate: he sends them to an abandoned monastery instead, where they learn trades, set up a factory, and run it collectively. The lost boys become upstanding Soviet citizens.

In one scene, midway through the film, a counterrevolutionary leaves a wounded boy to die on railroad tracks. A locomotive pulls near, but suddenly red flags appear, and a band strikes up “The Internationale”—the boy is saved. That scene of rescue so enthralled Murray that he leaped to his feet and raised his palm in a fervent Pioneer salute. Like the Soviet orphan, the orphan of Crotona Avenue found deliverance with the Communists.

He threw himself into Pioneer activities, especially helping evicted people. Many adults in East Tremont were losing not only their jobs but their homes. Landlords would simply put their possessions out on the street. When that happened, Young Pioneers would swing into action and haul the refrigerators, furniture, pots, and pans back inside.[22] The first time Murray got hit by a cop with a billy club, it was while carrying an evicted family’s furniture back up a stairwell.

Like their adult counterparts, the Pioneers marched in demonstrations and parades, most memorably those on May Day, the workers’ holiday. They would assemble at the Battery and march uptown, led by the party’s central committee, carrying a huge red banner. Then came the red trade unions and the unemployed. Bands played “The Internationale” and European songs of struggle and even folk songs. Then came the benefit societies and various front organizations. Then came the teenagers of the Young Communist League (YCL).[23]

At the very end came the Young Pioneers, wearing blue uniforms, red bandanas, and garrison caps with a red star. Murray’s East Tremont branch carried its red and gold banner, with a hammer and sickle. Others carried homemade placards reading, “Toward a Soviet America.” As they tried to march in military formation, they sang, “With ordered step, red flag unfurled, / We’ll make a new and better world! / We are the youthful guardsmen of the proletariat!”[24] The onlookers would give them a hearty round of applause—after all, they were the next generation.

The Communist movement of the early 1930s was very radical. In fact, it was the most ultraleft political movement in American history. And within that most ultraleft of movements, the two youth organizations, the Young Pioneers and the YCL, were the most ultraleft sectors. The Pioneers, Bookchin later recalled, were “super-revolutionaries.”[25]

In 1928 Stalin had announced to Communists worldwide that capitalism was entering its death throes and that the final revolutionary upheaval was at hand. Communist parties, he said, must initiate armed uprisings. They must not work with Socialists, who by refusing to acknowledge the vanguard role of the Communists were overtly counterrevolutionary. Stalin was enraged by the Socialists. In fact, their stubborn wrongheadedness, he proclaimed, made them villains, twins, on a par with capitalists—with fascists even. Stalin advised the international Communist movement that Socialists were “social fascists”—the Communists’ outright enemies.

Murray and his fellow Pioneers must have wondered: Were the Socialist kids at school really so evil? Was Norman Thomas, the Socialist Party leader, truly as wicked as a capitalist? Was Franklin Roosevelt actually a political twin of the Nazis? Pioneer meetings taught that they were. According to the Daily Worker, the Communist newspaper, FDR was “the leading organizer and inspirer of Fascism in this country,” fronting for a “hidden dictatorship” of bankers and industrialists.[26]

If the confused Pioneers had any further objections, their older peers could have set them straight. Back in January 1919, when the great German leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht had tried to make a Communist revolution in Germany, the Social Democrats—who had just come to power—had had them killed using a right-wing paramilitary group. That atrocity became, in Communist lore, like a primal blood-crime, committed by Social Democrats. Thereafter Social Democrats everywhere could never be forgiven—their sin was indelible and inexpiable.

As the economic crisis deepened in the early 1930s, the American Communist movement grew quickly. Many people who had lost their jobs or been evicted from their homes were grateful when Communists moved their furniture back or organized demonstrations and strikes on their behalf—sometimes whole neighborhoods would participate.[27] The party’s fiery rhetoric—about how the capitalist world was wracked by crises and plunging toward fascism and imperialist war—touched a nerve among the unemployed and the homeless alike: capitalism did indeed seem to be teetering. And then the Communists would tell them about the Soviet Union, the workers’ fatherland. While signs at American factory gates said “no work,” Soviet workers were marching confidently to work in factories. Planned, nationalized production was keeping people’s bellies full, it seemed, while capitalism was leaving people hungry. Amid “raging waves of economic upheavals and military political catastrophes,” said Stalin, “the Soviet Union stands apart like rock, continuing its work of socialist construction.”[28] So it was that between 1930 and 1934, the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) recruited almost fifty thousand new members.

Rose Bookchin was still existing on her ex-husband’s alimony payments, but around 1932 Nathan stopped sending them. Broke, Murray and Rose were now the ones evicted for nonpayment of rent, their furniture heaped on the sidewalk. They found a smaller apartment but couldn’t pay the rent and got evicted again. They scuttled from one boardinghouse to another, sometimes a new one each month. Once in 1934 Murray had no shelter for three days, so he slept on the overpass bridge of the 149th Street subway station, along with other homeless people.

He put cardboard inside his shoes to cover the holes. His snap cap and leather jacket hung in tatters on his thin frame. He and Rose waited in breadlines outside churches, hoping for a bit of soup and bread, alongside gaunt Great War veterans, their medals pinned to their shabby jackets. Sometimes formerly wealthy men waited with them, quietly, wearing overcoats with now-worn velvet collars.[29]

Murray had to grow up fast, and he needed a job. Once again the Communists came through for him: around 1932 or 1933 they gave him work selling the Daily Worker on his home turf. So every twilight he would head over to the Simpson Street IRT station, don an apron, and meet a delivery truck, along with other boys. He would pick up a fifty-paper bundle, then head up Simpson Street to Crotona Park. In those days, the city parks had political identities, and Crotona was Communist territory—an excellent spot to sell this paper. In summer evenings starting around seven-thirty, East Tremont residents (having no televisions yet) would mill around in the park, near Indian Lake, and talk politics.

They would talk about Adolf Hitler, and how the German working class absolutely must stop the Nazis in the coming elections. Stalin will make sure the German Communists organize a revolution and keep Hitler from power, someone might have said.

Even better, someone else might have jumped in, the German Communists and Socialists should join forces, form an electoral alliance, to shut the Nazis out!

No! It’s out of the question! another might have objected. We can’t work with Socialists! Those bastards murdered Luxemburg and Liebknecht! Nazism and Social Democracy are twins! Stalin said so![30]

As the argument raged, people would call the Daily Worker boy over and buy a newspaper, sometimes using it to bolster their case. With the nickels and dimes Murray took in, he could buy food for himself and Rose the next day. But even more important to him, he could listen in on the arguments and discussions, and he absorbed all he could from the verbal fray.

In fact, he couldn’t get enough of it. After he’d sold all his papers, he’d head over to East Tremont and Crotona, where the open-air street-corner meetings would just be getting underway. Communists, Socialists, and Trotskyists had designated corners at the intersection: their respective orators would set up their speaker stand, clear their throat, and then start declaiming about capitalism and revolution and fascism. Murray, moving from one to the other, hung on every word.

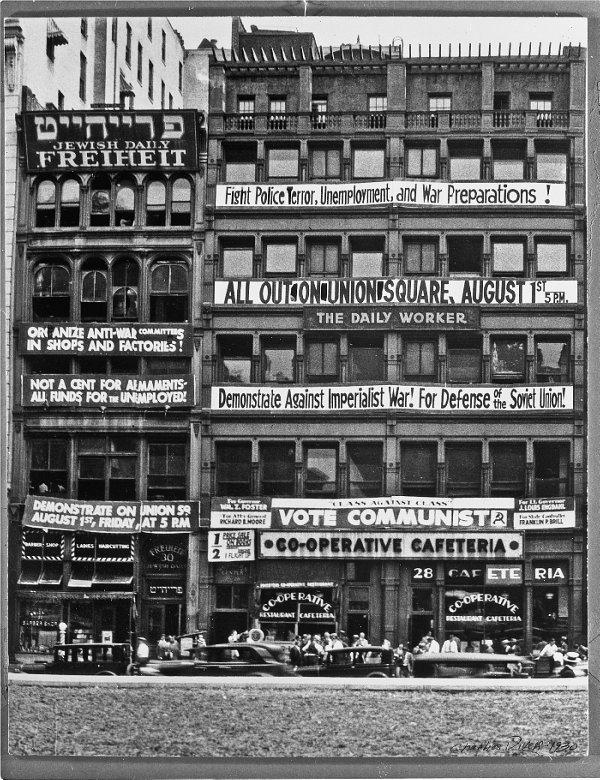

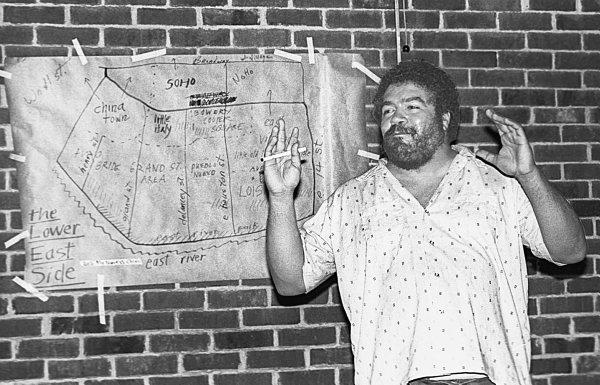

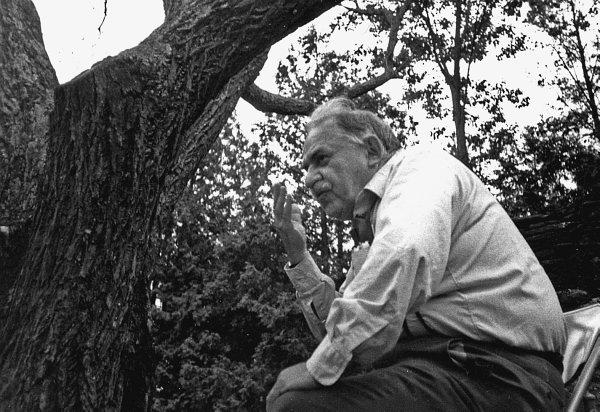

So eager was he to learn more about the Marxist ideology that underpinned his new family that he played hooky from public school and went into Manhattan to attend the Workers School. The CPUSA had established this Marxist academy in its headquarters building near Union Square (figure 1.1).[31] Taking a seat in an upstairs classroom, Murray would raptly sit through discourses called “Fundamentals of Communism” and “Political Economy.” A year or two later, he took a class on Das Kapital. The instructor, to his astonishment, had memorized all of volume one, or so it seemed. If you called out a page number at random, he could recite the page contents word for word, Murray told me. Their proficiency and scholarship were breathtaking.

Charles Rivers Photographs Collection, Tamiment Library, New York University. Photographer: Charles Rivers.

During the five years when he was its eager student, the Workers School gave him intensive and disciplined training in orthodox Marxism and Leninism. After class the students would go downstairs to the Cooperative Cafeteria, on the ground floor, and keep talking to any willing lecturers, like the American party leader William Z. Foster. “Cafeterias were the equivalent of European cafés,” Murray recalled. “They were all over New York at that time—get a cup of coffee, sit around a table, twenty or thirty people, with one of the maestros, and we’d quiz them.” They’d tell the students about the intraparty faction fights, or their trips to Moscow, where they’d met leading Russian Communists.[32]

The Pioneer meetings, Crotona Park, the street-corner oratory, the Workers School—they were all one big university for Murray. The passionate political discussions made life, “infused with radical politics,” perpetually exciting.[33] Soon he would know enough to join the discussions himself.

* * *

When their homelessness finally became unbearable, Rose swallowed her pride and applied for New York City’s municipal home relief program. She qualified, and the agency found an apartment on 177th Street for her and her son, and it even paid the rent. At least for now, Murray’s living situation was secure.

When a Young Pioneer reached the age of fourteen, he or she could be co-opted into the teenage organization, the YCL. But by 1934, thirteen-year-old Murray showed such promise that his elders brought him into the YCL a year early. He considered it a great honor.

At YCL meetings, at the branch’s headquarters on East Tremont Avenue, his Bolshevik education continued, with even greater intensity. The Young Communists acted like the Russians they all admired, even wearing the garb of commissars as depicted in Soviet movies: leather jackets and boots. They were in training to be commissars themselves, leaders of the revolution, members of its elite vanguard. Once the capitalist system entered its final crisis, their mission would be to lead the proletariat to socialism, and to create the proletarian dictatorship that would eliminate private property, socialize production, and distribute wealth according to need. Eager to fulfill their historic mission correctly, these zealous revolutionaries applied themselves to identifying the right strategy with painstaking care. The regular weekly YCL meeting wasn’t enough for them: when it was over, they moved to a cafeteria to discuss, say, Lenin’s State and Revolution and debate its meaning for the American situation, until two or three in the morning.

Murray and his comrades obsessively analyzed newspapers for signs of capitalism’s terminal crisis—and in the year 1934 the signs were many. In February, Socialist workers in Vienna raised red flags and mounted an insurrection, fighting in the streets with rifles and machine guns. The Young Communists, sleepless, waited bleary-eyed through the nights by their radios for news of the uprising—which was soon, heartbreakingly, crushed. In April, workers at the Auto-Lite factory in Toledo, Ohio, went on strike and clashed with the National Guard in the “Battle of Toledo”—two were killed. In May, Communist teamsters in Minneapolis organized a trucking strike that turned into a general strike that shut down the entire city. In July, Communist longshoremen struck at the port of San Francisco. Other workers joined them, to the point that a general strike closed much of that city, too. In October, coal miners rose up and gained control of Asturias, Spain. Murray and his comrades, in feverish anticipation, were sure the Spanish miners would proclaim a Soviet republic.[34] But then a general named Francisco Franco appeared on the scene, leading the Spanish Foreign Legion northward; after three weeks, his troops quelled the uprising, killing thousands.

The Young Communists cast many wistful gazes on Germany, the country that Lenin had hoped would make the next socialist revolution. But contrary to all expectations, the KPD, the German Communist Party, was eerily quiet. It had done nothing to stop Hitler from coming to power in January 1933, and now nothing much was heard from the German comrades at all. Still, the Nazis surely didn’t stand a chance against the powerful, well-organized German working class. Any day now the YCL-ers expected to read news of a German Communist-led strike or call to arms against Hitler.

Murray showed such promise as a leader and an ideologist that the YCL leadership tasked him with leading a Young Pioneer troop. Then they made him education director for his YCL branch. That meant that he set the agenda for the branch’s educationals: in effect, he became its political commissar. He went to executive committee meetings and sat on the Bronx County committee.[35] Far from resenting all these meetings, he attended them eagerly, proud to be playing such an important role in the movement.

“Every day was an experience,” he later recalled, for the world seemed on the brink of a profound upheaval. “The magic and romance of the October Revolution, the drama of it,” suffused his life. How he chose to spend his time—seek out an open-air meeting, go to a demonstration, jump into a debate in the park—could, he knew, affect the course of world history. Even a young boy in the Bronx could help push the revolution forward, indeed was required to—and it would have been unthinkable to abjure that profound responsibility. Far from seeming onerous, the great task made life exhilarating.[36]

He understood, let it be said, that the Communist Party was no democracy. He and his comrades could debate issues, even at YCL meetings, but once the party adopted a position, and once the Young Communists were out in public, they were required to defend it, whether they agreed with it or not.

Murray disagreed, for example, with the party’s demonization of Socialists as “social fascists.” He had friends who were Socialists—members of the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL). Sometimes he went to Socialist rallies to observe them, quietly, and found them to be just as radical as the Communists—they waved the red flag, called themselves Marxists, and defended the Soviet Union.

But when the CPUSA commissars ordered him and his fellow commissars-in-training—on pain of expulsion—to disrupt Socialist open-air meetings, they all obeyed. They would go and listen and wait for the question period, then challenge the speakers about the murders of Luxemburg and Liebknecht. The harassment would sometimes lead to fistfights and break up meetings.

They did the same at Trotskyist meetings. But when they harassed these speakers as “social fascists,” the Trotskyists argued back forcefully. Your so-called comrade Stalin is executing millions of peasants in Ukraine! they might counter. He’s forcing them to collectivize—and if they resist, he cuts off their food. It’s mass murder by starvation!

To which Murray and his comrades might reply, Those kulaks—the peasants Stalin killed are actually rich and privileged. We can’t let them stand in the way of building socialism!

To which the Trotskyists might retort, Stalin expels everyone who doesn’t agree with him 100 percent! He even expelled Trotsky, Lenin’s comrade in the October Revolution, and sent him into exile!

Murray respected these dissident Communists—their arguments often made sense, and they seemed like decent people. But he knew, too, that the Communists were the exclusive vanguard, leaders of the march to a glorious future. By virtue of standing outside the vanguard, the Socialists and Trotskyists were “objectively counterrevolutionary,” enemies of the international proletarian revolution. So it was possible to justify harassing them.

Yes, the Soviet Union was authoritarian, but sometimes people must abdicate claims to freedom in the name of moving history forward, he rationalized. As Engels had said, freedom is the recognition of necessity. Besides, once the final conflict was underway, the proletariat would need a centralized military-style organization to defeat the US Army, where taking orders would be a necessity.[37]

The YCL-ers had no doubt that they would ultimately defeat the American bourgeoisie and transform a nation of 125 million people into a socialist society—“the inexorable laws of history” were on their side.[38] After all, only a few thousand Bolsheviks had changed Russia, and one man—Lenin—had galvanized an entire city around the simple slogan “Peace, bread, land.” Once they prevailed, the new society would actually be more democratic than the bourgeois republic it replaced. So broad would be the democracy that the very word would disappear from the popular vocabulary. For the sake of achieving that glorious outcome, the YCL-ers were willing to set aside democracy temporarily.

Until that utopian vision was fulfilled, however, a huge responsibility weighed on these teenagers’ scrawny shoulders: it would be up to them to meet the challenge of history and lead the revolution.

No wonder he couldn’t sit still in classes at Morris High School. And when he did show up, he turned classrooms into battlegrounds. When the American history teacher disparaged John Brown as a fanatic, Murray rose to fervently defend his abolitionist hero. When the European history class studied the French Revolution, the teacher would sigh, “All right, Bookchin, you can take over now and defend Marat!” Murray would stand up and extol the far-left Jacobins. Sometimes, he told me, he just wore the teacher down. “Go ahead, Bookchin,” one teacher groaned, “present your Red point of view.”[39]

But as often as not, Murray and his comrades skipped school and roamed the streets, looking for ways to spark an insurrection. When they came across a picket line of striking workers, they’d fall in, no questions asked.

Or they’d join an illegal demonstration, carrying banners and placards, swaggering and yelling their way to city hall. There “Cossacks”—police on horseback—were lined up along the street. At a signal, the Cossacks would charge toward the demonstrators, brandishing clubs. As the hooves thundered, the boys grabbed their placards and removed the wooden sticks, using them as makeshift clubs, and “whacked the hell out of the police,” Murray told me. “Lots of times we got them off their horses, and we injured them enough that we squared off pretty well.” Then Black Marias—police vans—would arrive and round them all up and take them to the Tombs. Shoved into a big cage, the arrestees would stink it up with a collective piss-in. They were quickly released.[40]

The CPUSA commissars, impressed once again by Murray’s precocity, soon appointed him a street-corner orator, for the open-air meetings. They gave him the opening slot at the intersection of East Tremont and Crotona and assigned him the crucial initial task of attracting a crowd. Now, as soon as he finished selling his Daily Worker in the park, he’d rush over there and set up the YCL stand.

He’d mount the platform, clutch the railing, and try to look fierce and commanding. Then he’d shout at the top of his lungs, “Comrades and fellow workers—I herewith open this meeting of the Young Communist League!” And he was off. “We face today the possibility of a second world war that will wipe out Western civilization.” To keep a group’s attention, he learned, he had to be extremely expressive, gesticulating and clenching his fists.

A crowd would collect. Sometimes Socialists showed up to harass him with hostile questions about, say, the 1921 rebellion of the Kronstadt sailors against Bolshevik tyranny—the Red Army had quashed it with much bloodshed. Murray had to respond by asserting the party’s rationalizations: that the sailors were petty bourgeois, or that their revolt had been financed by imperialist powers. If a Trotskyist challenged him on, say, the Stalinist belief that “socialism in one country” was really plausible, Murray would have to be ready to argue the Stalinist line that socialism existed in the Soviet Union.[41]

If he proved unable to answer a critic, the audience would laugh him down, and his public humiliation would reflect poorly on his whole YCL branch. So it was important to snap back decisively. And when he gave a good answer, they’d cheer, and his confidence soared. He got better at it, to the point that his listeners would hear him out. As training in public agitation, it was rigorous but effective—he learned to speak forcefully and dramatically, without notes. Speech-making soon became a pleasure. He couldn’t wait for nightfall: for most of 1934, he orated on that street corner nearly every evening.

Meanwhile in France, on the night of February 6, far-right forces took to the streets and rioted against a leftist coalition government that had been in power in Paris for two years. As a result of this pressure, that government fell, and a more conservative one took its place, acceptable to the Far Right. Suddenly a fascist coup seemed like a possibility in France. A few days later, the French Communists did something strange, something that their German counterparts had not done a year earlier: they defied Stalin’s “social fascist” demonization policy and joined forces with the Socialists to carry out a general strike. In fact, that June, French Socialists and Communists formed a unity pact.

Strangely, at least to the Bronx YCL-ers, the top Communists raised no objection. In fact, Stalin approved the collaboration. Hitler’s Nazis were rearming Germany, he said, and they might one day attack the Soviet Union. During 1934–35 he had decided that the Soviet Union must form defensive alliances with capitalist governments to ward off Nazi aggression. On May 2, 1935, France and the Soviet Union signed a mutual assistance pact.

Stalin wanted to form more such alliances, with other capitalist governments, but the chances were slim as long as his Communist parties were trying to overthrow those very governments. So the word went out to Communist parties around the world: cease vilifying Socialists as “social fascists” and embrace them as allies. Communists should even, if possible, follow the French model and join forces with Socialists, even with Social Democrats, to form so-called Popular Front governments that would be friendly to the Soviet Union.

The French Popular Front alliance came to power in June. The ultrarevolutionary period was over.

Perhaps it was Gil Green, head of the American YCL, who in late 1935 informed Murray and the other young commissars-in-training that they were to stop attacking Socialists and start working with them.[42]

Murray was relieved at first—no longer would he be required to torment his Socialist friends at their meetings. He’d never really thought they were “social fascists” anyway. But he was dismayed that the party’s new Popular Front line called for making alliances not only with Socialists (who were fellow revolutionaries) but with Social Democrats (who were reformists). Wasn’t that class collaboration? What about socialist revolution?

The party commissars told him, in effect, to forget about revolution.[43]

Murray was dumbfounded. It contradicted everything they had hitherto taught him. The reversal was incomprehensible. Shocked, he stopped attending YCL meetings and went looking for a group that was still revolutionary. He found one in the Young Spartacus League, a group of Trotskyists.

They would surely have welcomed the talented young commissar. Surely, too, they explained to him that the Soviet Union’s new Popular Front line, abjuring socialist revolution, should have come as no surprise. Stalin was a counterrevolutionary and had been for a long time—he had hijacked the Russian Revolution and diverted its momentum into the creation of a new tyranny that, far from liberating the workers, was oppressing them in new and increasingly atrocious ways.

Trotsky, by contrast, was still a Bolshevik revolutionary and wanted to put the revolution back on course. He intended to mount an uprising to overthrow Stalin, take control of the Soviet Union, and revive the spirit of true Bolshevism. He would succeed, they said, because unlike Stalin, he had the mighty proletariat as his social base.

Murray decided to join these like-minded comrades and gave them his name and address.

In the spring of 1936, perhaps while at the movies with his mother, Murray saw a black and white Movietone newsreel, showing footage of massive demonstrations in Spain. Thousands of workers were marching in the streets of Barcelona and Madrid, with clenched fists, wielding rifles and flags.

That February, the Spanish people had elected to power one of those Popular Front governments, a left-liberal coalition that included the Communists. But Spain’s reactionary generals despised the Popular Front, so much so that, led by General Franco, they commenced a military rebellion against it and indeed against the Spanish Republic itself, in the name of the country’s most reactionary military and religious traditions. Setting out from Spanish Morocco, they crossed Gibraltar and rolled through Spain, capturing numerous cities as they went. In some places, however, like Catalonia, resistance from popular militias beat them back.

A civil war had begun. To support the generals’ revolt, Mussolini and Hitler sent troops and tanks. But only one country came to the aid of the beleaguered Spanish Republic: the Soviet Union, which sent tanks, fighter aircraft, guns, and military advisers. In fact, Stalin’s Comintern was now encouraging Communists everywhere to join international brigades, to fight fascism in Spain.

Murray volunteered for the American brigade (named after Abraham Lincoln), but at fifteen he was too young to fight in Spain himself, and as much as he implored them, they refused. Determined to help the Spanish proletariat nonetheless, he raised money for arms and medical aid. But to do so he had to rejoin the YCL. Thus six months after he dropped out, he returned. “I didn’t go back to support Stalinism,” he said. The YCL just “gave me an avenue whereby I could express my support for the Spanish loyalists.”[44] He’d go into the subways and launch into a speech, then hand out leaflets that urged, Support the antifascist struggle!

During the six months of Murray’s absence, the Communist Party had undergone a dramatic transformation, thanks to the Popular Front policy. When he reentered his old branch headquarters on East Tremont Avenue, he was shocked to see that on the wall where a red flag had once hung, there was now an American flag. Images of Marx and Engels and Lenin had been replaced by portraits of Washington and Jefferson and Lincoln. When the commissars spoke, no more did they hail the coming proletarian revolution—now they voiced full-throated patriotic support for President Roosevelt. Another wall bore the slogan “Communism is twentieth-century Americanism.” In November the party’s political bureau formally adopted the New Deal’s prolabor legislative program as its own.[45]

When it came to attracting new members to the Communist Party USA, the new Popular Front policy was a huge success. Liberals and labor unionists flocked to the Popular Front banner, suffused with admiration for the workers’ paradise—the Soviet Union—and its fully employed workforce.

Meanwhile in Moscow, even as Stalin was anxiously courting Western liberals, he was also busy rewriting history. He and his henchmen were putting the still-living revolutionaries of 1917 on trial, charging them with conspiring to assassinate Stalin and, working with the Gestapo, turn the Soviet Union over to fascism. At a show trial, in August 1936, the prosecution offered no evidence to prove its case against them, because there was none—the verdict had been decided in advance. Yet the accused, standing on the dock, repented their supposed crimes in spectacular self-incriminations. They were found guilty and executed. Leon Trotsky, living in exile, was sentenced to death in absentia.

Murray understood that the charges were absurd, that the confessions had been extracted by torture. As for Trotsky, the more Stalin denounced him, the more Murray was intrigued by the onetime commander of the Red Army. He read his three-volume History of the Russian Revolution, in its eloquent literary translation by Max Eastman, and was floored. Contrary to everything the YCL had told him, Trotsky had formidable intellectual power, both as a historian and as a social theorist. Moreover, his account of the revolution showed that the YCL leadership had lied when it claimed the Bolsheviks had banned factions even before the 1917 revolution. On the contrary, before the seizure of power, dissent had been allowed.

At a second Moscow show trial, in January 1937, seventeen more old Bolsheviks were speciously charged, convicted, and executed. By now, in the Stalinists’ universe, Trotsky had become the generic symbol of satanic evil. Stalinists routinely branded all their enemies as “Trotskyist-fascists” or “Trotskyist-imperialists” or “Trotskyist-Zionists.”

In response, Trotsky himself, in exile since 1927 and now residing in Coyoacán, Mexico, assembled a dossier to refute Stalin’s charges against him. An impartial international commission agreed to examine his case, headed by the eminent liberal American philosopher John Dewey. In April 1937 Dewey traveled to Mexico and spent a week interrogating Trotsky. He found his testimony straightforward and evidence-based. He declared Trotsky not guilty and even called the encounter “the most interesting single intellectual experience of my life.”[46]

In Murray’s eyes, Trotsky had become truly heroic. Still, he remained a YCL member in order to do support work on behalf of the Spanish proletariat. And when dealing with the commissars, he kept his head down.

One day the head of the YCL’s Bronx County Committee noticed that at a meeting young Bookchin seemed strangely inattentive and asked him what was going on. Murray shrugged. “Comrade Bookchin,” the man said, “I’ve gotten reports that you have views that aren’t compatible with those of the movement. And I’ve heard you express some sympathies for the traitors being tried in Moscow, the fascists, Trotskyists. And I’ve heard that you have some differences with the Popular Front. You’ve been in the movement for a long time. We don’t want to lose you. Would you like to see a comrade psychiatrist?” Murray stalled, saying he’d think about it.[47]

During the 1930s a new working class had emerged in the United States, employed in the burgeoning auto, steel, rubber, textile, glass, and electrical industries. These industrial workers, many of them immigrants, clamored to join labor unions, but the existing ones wouldn’t admit them. In November 1935, United Mine Workers president John L. Lewis created the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO), as an umbrella for industrial unions like the United Electrical Workers (UE), the United Auto Workers, and the United Steelworkers. Industrial workers stampeded into them, then participated in sit-down strikes, which were wildly popular and wildly effective.

The UE wanted to establish a foothold in the factories and mills and machine shops of northern New Jersey and needed organizers. So it turned to the people who had the most experience in such tasks: Socialists and Communists. UE organizers noticed Murray’s oratorical talents and physical bravado. He was only sixteen but looked older, so in 1937 they recruited him. He took the ferry across the Hudson, then the train to Jersey City. He’d find a spot in front of a factory, then stand up and address the workers, extol the might of the insurgent proletariat, and urge them to go to the next UE meeting.[48]

New Jersey’s political establishment, however, was determined to keep labor unions out of the state. Governor Harold Hoffman minced no words—he would eject CIO organizers “by bloodshed if necessary.” Jersey City boss Frank Hague expressed the same attitude: “I am the law. I decide; I do; me!”[49] Hague forbade the CIO organizers to use public places for rallies and made sure they couldn’t rent meeting halls—when workers, mobilized by Murray and his comrades, arrived at the local hall, they found the doors locked. Other times, when the organizers tried to distribute leaflets, company goons charged after them with axes and even shotguns,[50] and if they caught up with the terrified youths, they’d beat them and then drop them outside the county line, or stuff them onto a train and ship them back across the river. By such means did Boss Hague keep labor unions out of Jersey City.[51]

Unknown to Murray, thousands of miles away in Mexico, the exiled Trotsky was studying newspaper reports of these very events. Boss Hague was “an American fascist,” the old Bolshevik concluded, and his tactics were “a rehearsal of a fascist overthrow.” The only way to stop him, he thought, was to organize workers into defense committees to fight them physically. Otherwise “we will be crushed. … I believe that the terror in the United States will be the most terrible of all.”[52]

Through it all, Murray was studying the Movietone newsreels for news about the Spanish Civil War. It wasn’t just about fighting Franco anymore. The films showed Spanish people marching with clenched fists, singing “The Internationale,” waving flags. Clearly something more than a civil war was going on.

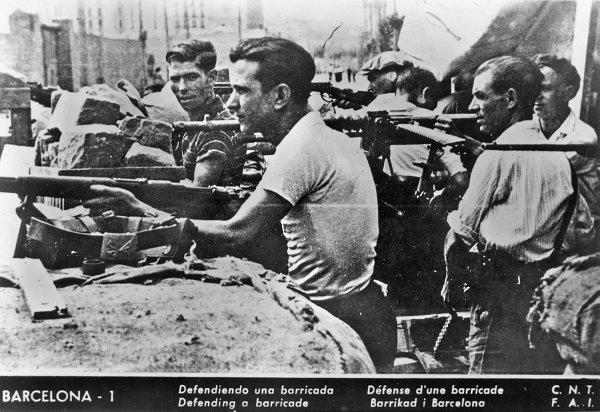

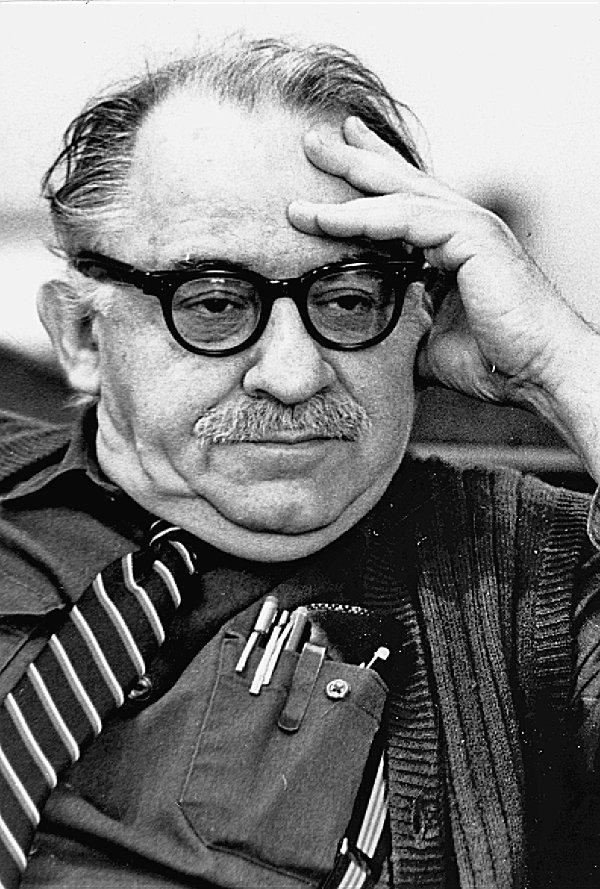

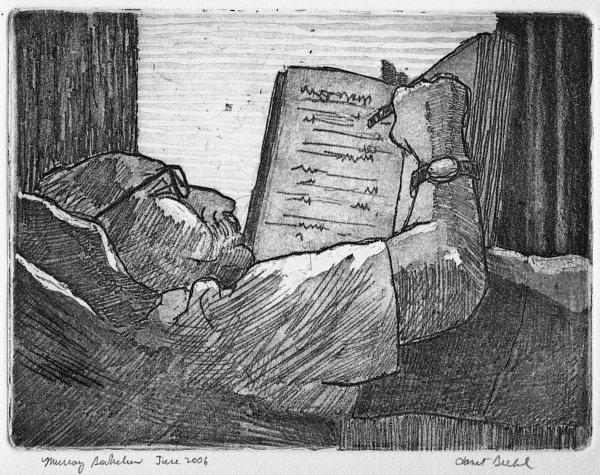

Then, in early May 1937, the Daily Worker reported that street fighting had erupted in Barcelona, the Catalan capital. The Barcelona proletariat, said the Stalinist organ, had mounted a pro-fascist uprising. It was nonsense, Murray understood immediately. Tossing the paper aside, he picked up the bourgeois New York Times, which told a much more credible story. “Anarchists tonight were in control of a part of Barcelona,” he read, “after a rising in which at least 100 persons have been killed.” The Catalan authorities had mastered the city center, but “the Anarchists control the suburbs and outlying districts” (figure 1.2).[53] In other words, the Barcelona uprising wasn’t fascist—it was anarchist.

Courtesy Fundación Anselmo Lorenzo, Madrid, and Labadie Collection, University of Michigan.

Anarchists! Who knew they even existed anymore, let alone that they were capable of organizing? Who were these anarchists, anyway?

He found answers by devouring George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia (1938), Felix Morrow’s Revolution and Counterrevolution in Spain (1938), and Franz Borkenau’s The Spanish Cockpit (1937). Starting in the late nineteenth century, he learned, panish workers had organized themselves into a huge, militant anarchist (actually anarcho-syndicalist) trade union called the National Confederation of Labor (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, or CNT). By July 1936, when Franco and the generals had tried to conquer Spain militarily, the CNT was quite strong, so much so that cenetista militias—organized along libertarian lines—had been able to defeat them in Catalonia and Aragon. Now finding themselves in political control of those areas, the CNT anarchists had collectivized factories and established workers’ committees to run them, and in the countryside they had collectivized farms. The workers and peasants were in control.

For years Murray had been hoping that every upsurge reported in the press would turn into a social revolution. Now, finally, after all the aborted efforts, here was one that had succeeded: a proletarian revolution. But bizarrely enough, it had been carried out not under the red flag of Bolshevism but under the black-and-red flag of anarcho-syndicalism. The Communists were supposed to be in favor of proletarian revolution, but now they were in power, as part of Spain’s Popular Front government, and instead of supporting this one, they actively sought to suppress it, indeed to dismantle the anarchist collectives and smash the anarchist militias, using the Popular Front’s military forces, which they controlled thanks to Soviet aid. The whole scenario was topsy-turvy. In May 1937, as Murray read in the Times, when the Barcelona anarchists took to the streets to defend their revolution, the well-armed Communists vanquished them, dooming the anarchist revolution.[54]

Reading Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, Murray became enthralled with the Spanish anarchists. “I said, they cannot be wrong! Not people like that.”[55] The more he learned about them and their revolution, the greater became his passion for them, and the more his hatred for the Stalinists grew. The anarchists’ revolution that the Stalinists had extinguished, Murray concluded, had been nothing less than the greatest proletarian revolution in history.

In mid-1937 Stalin’s Comintern dropped the Popular Front party line and adopted a new, even less revolutionary one, which it called the Democratic Front. Communist parties were now to accept as allies and members not just Socialists and Social Democrats but just about anyone. In East Tremont, a Bronx county leader visited Murray’s YCL branch to announce the new policy. He took no questions, permitted no discussion, just dropped the bombshell and left.[56]

Murray’s head was spinning. Only three years earlier, the CPUSA had been so ultrarevolutionary that it had excluded Socialists. Now, in the name of protecting the Soviet Union, the Young Communists were required to join forces with “even the vilest capitalist reactionary … even with J.P. Morgan.” And now thanks to the Popular Front policy, new people were flooding into the YCL who knew little and cared less about Marxist ideology. They hadn’t read Capital or any of the other texts, let alone master its arguments and memorize page numbers. YCL educationals deteriorated into travesties of their former selves. Instead of discussing Marxism, “a whole meeting will be taken up with such safe matters as selling tickets for some social affair.”[57]

Ominously, the more mindless the party became, the less it seemed to tolerate deviations or dissidence, aping Stalin’s dictatorship. More and more it vilified any dissent as Trotskyist. In the spring of 1938, as Stalin was demonizing Trotsky in yet another show trial, the CPUSA formally amended its constitution to prohibit its members from having a “personal or political relationship” with Trotskyists, who it said were “organized agents of international fascism.”[58]

Once again, a county official beat the path to the East Tremont YCL, this time to announce the ban on Trotskyists. When he was finished, one YCL-er spoke up, asking how they could identify a Trotskyite at future meetings. Perhaps the official eyed the questioner suspiciously when he replied: “Nine out of ten times, anyone who asks a question is probably a Trotskyite.” This was so brazen that other YCL members objected raucously. The party had to send out another official to cool them down.[59]

But the new line was serious: the Young Communists were ordered to spy on one another. Living at home with a Trotskyist family member was forbidden, and any YCL-er who did was required to move out.[60] Reading Trotskyist literature was excluded. Anyone suspected of associating with a Trotskyist was put on trial, subjected to vitriolic accusations, and forced to make a humiliating confession, in a facsimile of the Moscow show trials. Those found guilty—and they were many—were punished by expulsion.[61]

For Murray, as discontented as he was, expulsion was a frightening prospect, since he had no life outside the YCL. He hoped fervently that this new Democratic Front madness would prove short-lived, that the party would soon admit its mistake, drop the ally-with-capitalists line, and return to being a revolutionary party.[62]

But as the months passed, the inquisitorial mania, far from breaking, only intensified. The YCL leadership now detected Trotskyism even in a single word or in body language or a person’s tone of voice. Members were banned from touching Trotskyite literature with their fingers, as if it carried some infectious disease.[63]