Jere Kuzmanić

Peter Kropotkin and Colin Ward

Two ideas of ecological urbanism

1.1 What is environmental in anarchist approaches to space?

1.2 ‘The anarchist thread’ in ecological urbanism(s) — Historical overview

1.2.1 Production of ideas: The anarchist geographers, 1866–1899

Reclus and the nature-city fusion

Kropotkin and the countryside-city economic integration

1.2.2. The production of experiences, 1899–1939

The proposals for the agro-industrial symbiosis of the Spanish libertarians

The experiences of direct action

1.2.3. Urbanism from below: the anarchist architects of the second post-war period, 1939–1976

Colin Ward and direct action in housing

Giancarlo De Carlo: the architecture and urbanism of participation

John F. C. Turner: Housing and the neighbourhood made by users.

Anarchist urbanism ideas in the USA — Bookchin and Democratic federalism

Renaissance of academic interest in anarchist geography at the change of the centuries

1.3 Two visions of ecological urbanism

1.3.1. Summary of the key lines of comparison

1.3.2 On the continuation of the idea — comparison of key concepts

Comparison of Kropotkin and Ward: Key Concepts

Integration of city and countryside

Full bibliography (incomplete)

2.1. Periodicals and Mutual Aid

The birds know no boundaries — anarchist’s contribution to scientific debates

Mutual aid — a factor of joyful survival

Is nature urban? — Mutual aid and (re)production of resources

Free cities and ‘dark ages’ - Mutual aid and (re)production of space

Kropotkin’s (scientific) journalism — joyful survival in practice

A guide to post-revolution management of city-countryside relations

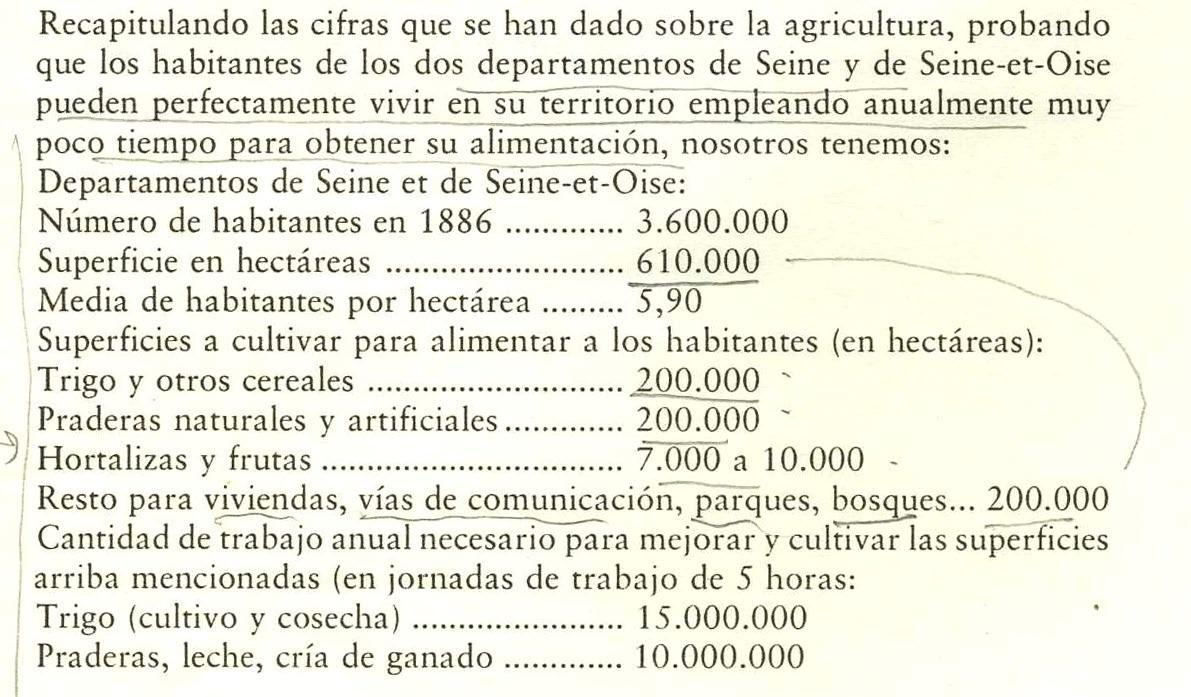

‘Bread, the revolution needs bread!’ — Kropotkin on food

Where could food come from? — Anarcho-capitalism vs anarcho-communism

How to supply food? — The city with few bottles of wine

Who gets to eat? — Collective justice vs individual freedom

Conclusion — How anarchists reterritorialized the economy?

2.3. Fields, Factories, Workshops

The triangle of geopolitics, economy and technology

Evolution of agriculture and rural industries

Integration of manual and intellectual labour

Full bibliography (incomplete)

What is housing from anarchist perspective?

The three revolutions of housing

Housing as tactic — from right to housing to self construction

3.2 An anarchist approach to environment

Environment (h)as political subject

Environment is reciprocal — Whose environment?

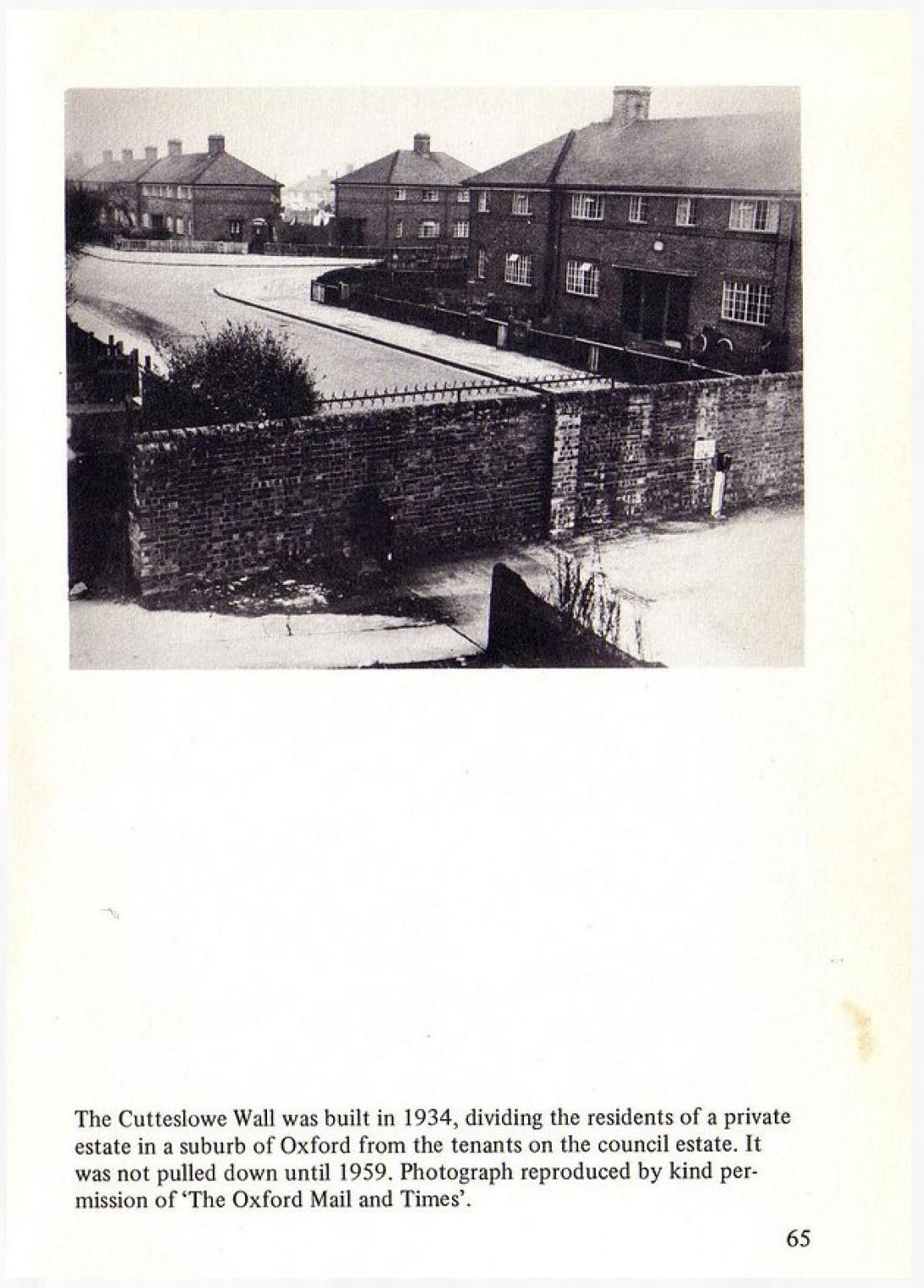

Environment is essentially social — Who owns the land?

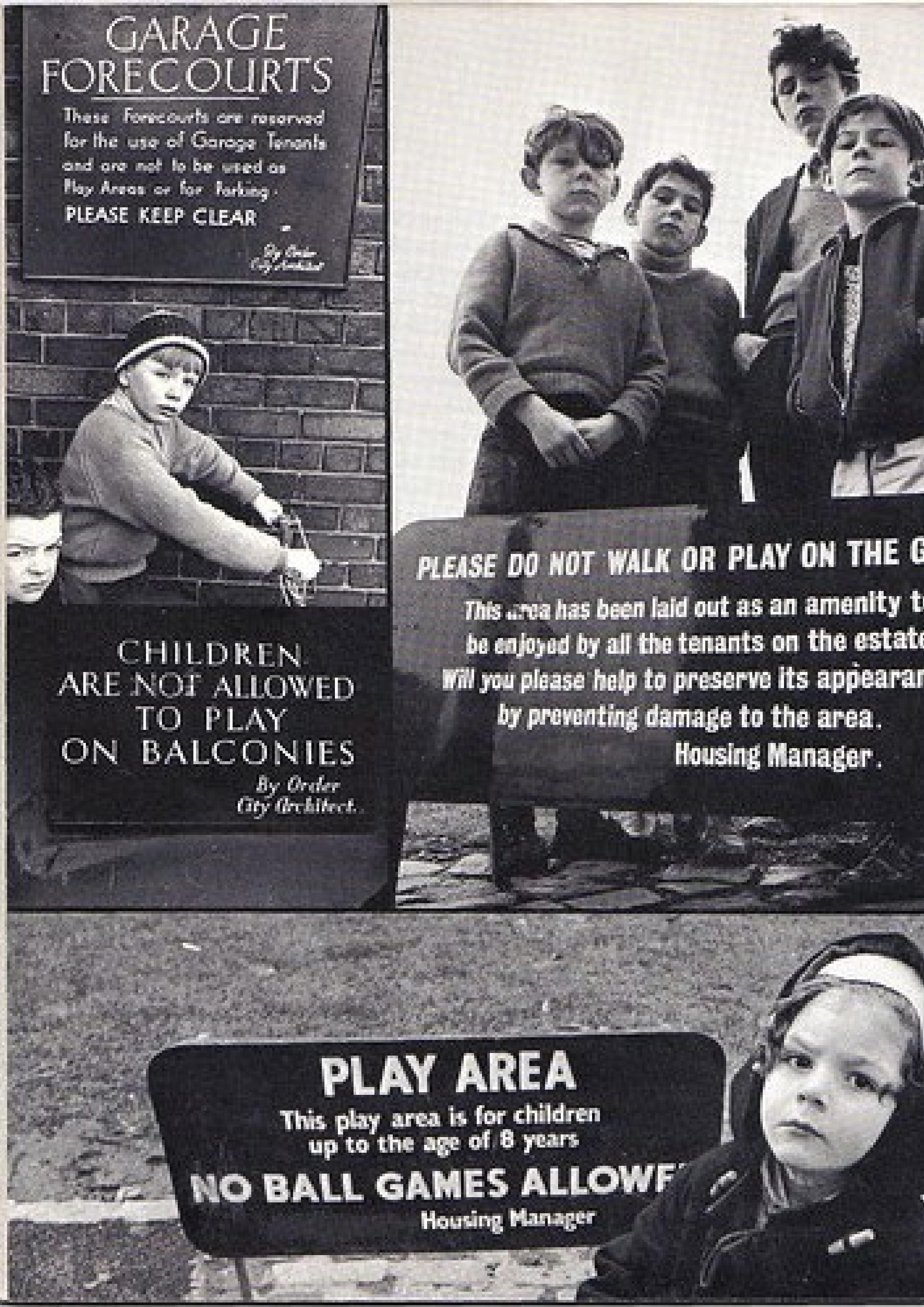

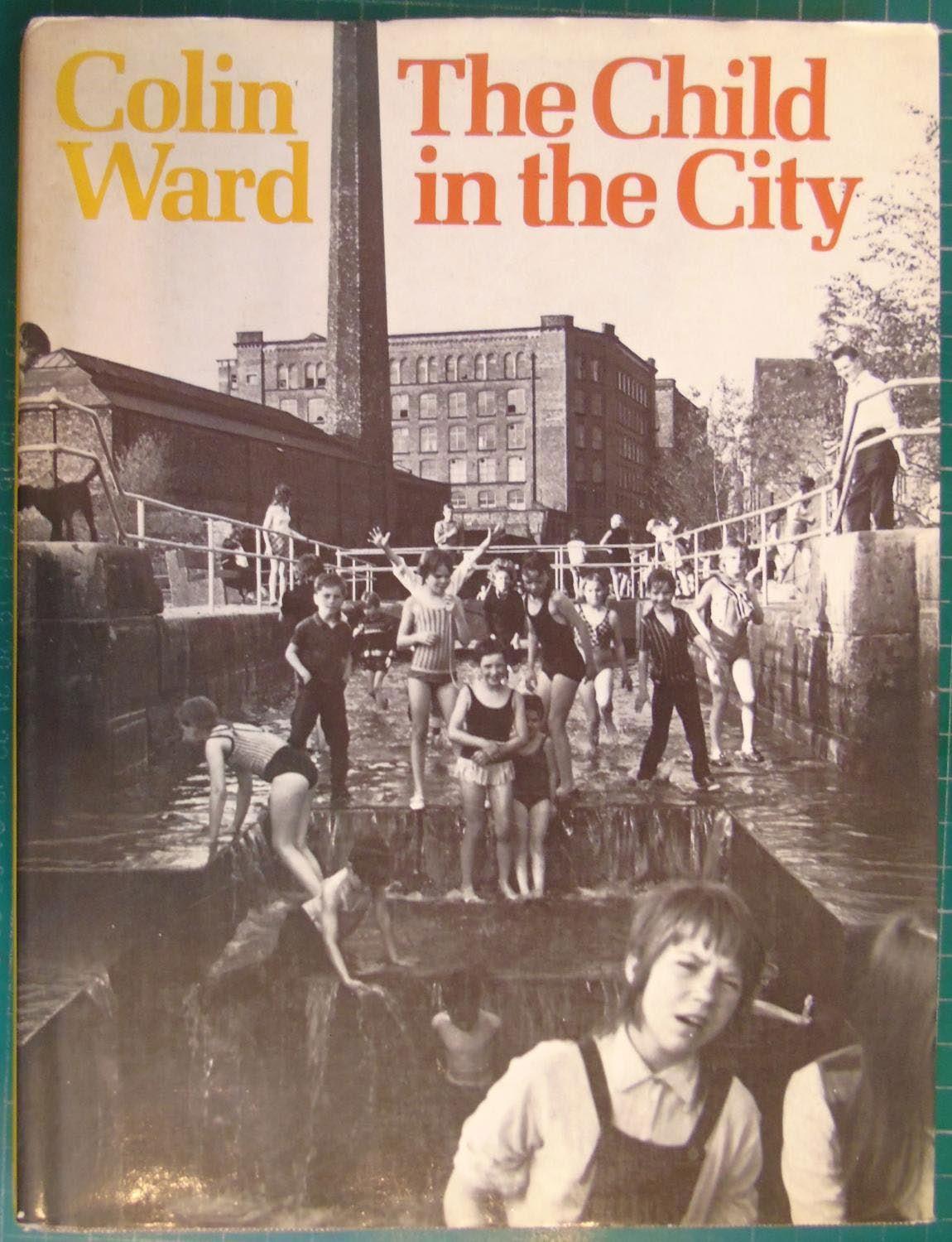

Environment is inherently personal — Child and the city

What could architects do in this triangle?

What is wrong with urban planning?

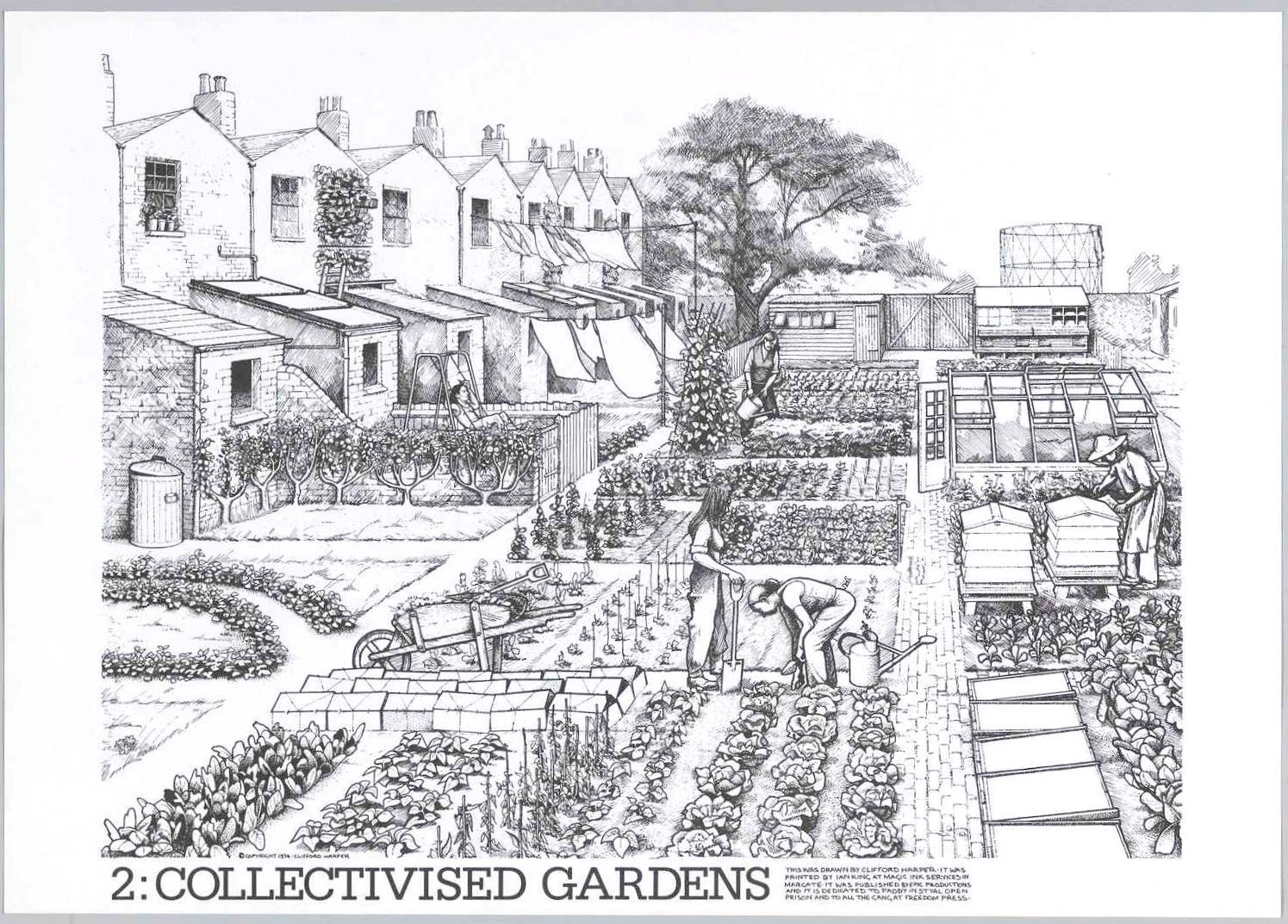

The Do-it-yourself Town Planning

1) Do something about Land Valuation

2) Help People House Themselves, Inside and Outside the City

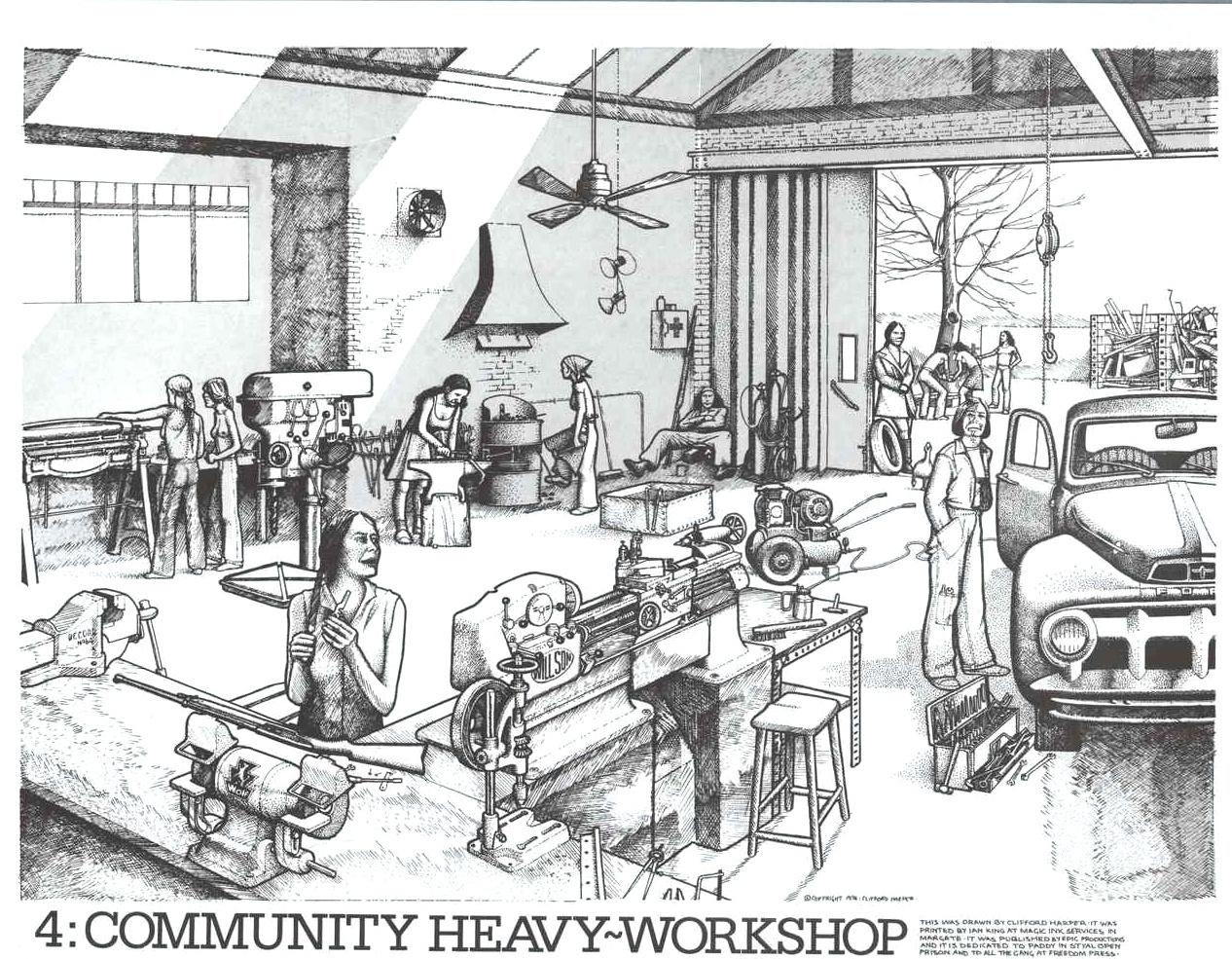

3) Give Real Encouragement to Small Enterprise

4) Making the cities green again

5) Find New Ways of Engaging the Young

6) Give access to Tools and technology

7) Change the Terms of the Debate

[Front Matter]

[Dedication]

The thesis is dedicated to David Graeber, who died on the 2nd of September, 2020. To his greatness in proving that anarchism is worth intellectual endeavour in the 21st century, as both, academically relevant and widely respected.

Goodspeed David! Thank you for the Debt.

[Metadata]

Master Universitario en Intervencion Sostenible en el Medio Construido

MISMEC

Escola Tecnica Superior d’Arquitectura del Valles

Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya

2019/2020

TFM — Trabajo Final de Master

(defended-September 2020)

Alumni: Jere Kuzmanic

jerekuzmanic@gmail.com

Mentor: prof. Jose Luis Oyon

jose.luis.oyon@upc.edu

The photo on the cover is made during the eviction of XM squat Bologna, Italy

Photo by: Michele Lapini, http://www.michelelapini.net/

The thesis is written and defended in English

[Abstract]

The thesis recapitulates the works of two anarchists, Peter Kropotkin and Colin Ward seeking the continuous thread of development of ecological urbanism as a political and spatial concept. As geographer and architect both imagined, wrote and inspired practices of production of space deeply rooted in ecology and spirit of self-organization. The literature review of primary and secondary resources will entangle the relationship between Kropotkin’s (proto)ecological geography with Colin Ward’s post-war self-management in urbanism. Both conceptions emerging from direct action, mutual aid and cooperation they will be presented through a comparison of their writings and the correlating the examples they inspired (Spanish anti-authoritarianist planning councils, 50s squatters movement, self-help housing communities etc. )

Their similarities and underlying values maintain the idea of an under-presented model of ecological urbanism that could be of significant relevance nowadays (i.e. in the context of urban degrowth, cooperative housing movement, etc.).

Keywords: Ecological urbanism, Peter Kropotkin, Colin Ward, history of urbanism, urbanism from below, city-countryside integration, self-organization in urban planning

Content

1 Introduction

1.1 What is environmental in anarchist approaches to space?

1.2 ‘The anarchist thread’ in ecological urbanism(s) — Historical overview

1.3 Two visions of ecological urbanism

1.3.1 Summary of the key lines of comparison

1.3.2 On the continuation of ideas — Comparison of key concepts

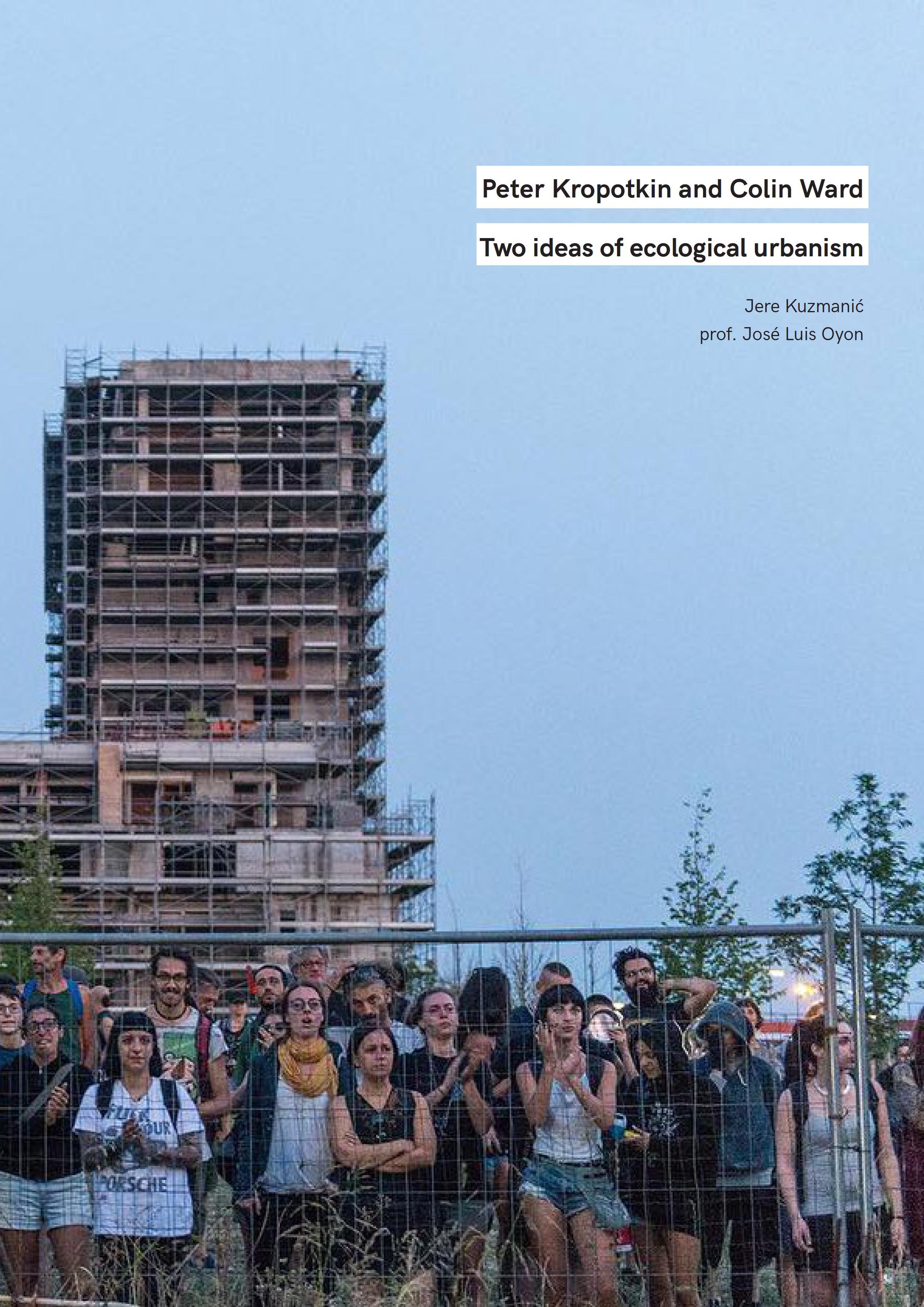

2 Kropotkin

2.1 Perodicals and Mutual Aid

2.2 The Conquest of Bread

2.3 Fields, factories and workshops

3 Ward

3.1 Anarchist approach to housing: Housing: An Anarchist approach (1974), Tenants Take Over (1972), Talking Houses (1990)

3.2 An anarchist approach to environment: The Child in the Country (1988), The Child In The City (1978), Talking to architects (1996)

3.3 An anarchist approach to urban planning: Welcome, Thinner City (1989), Do-It-Yourself New Town (1976)

4 The Dialogue

5 Bibilography

[Epigraph]

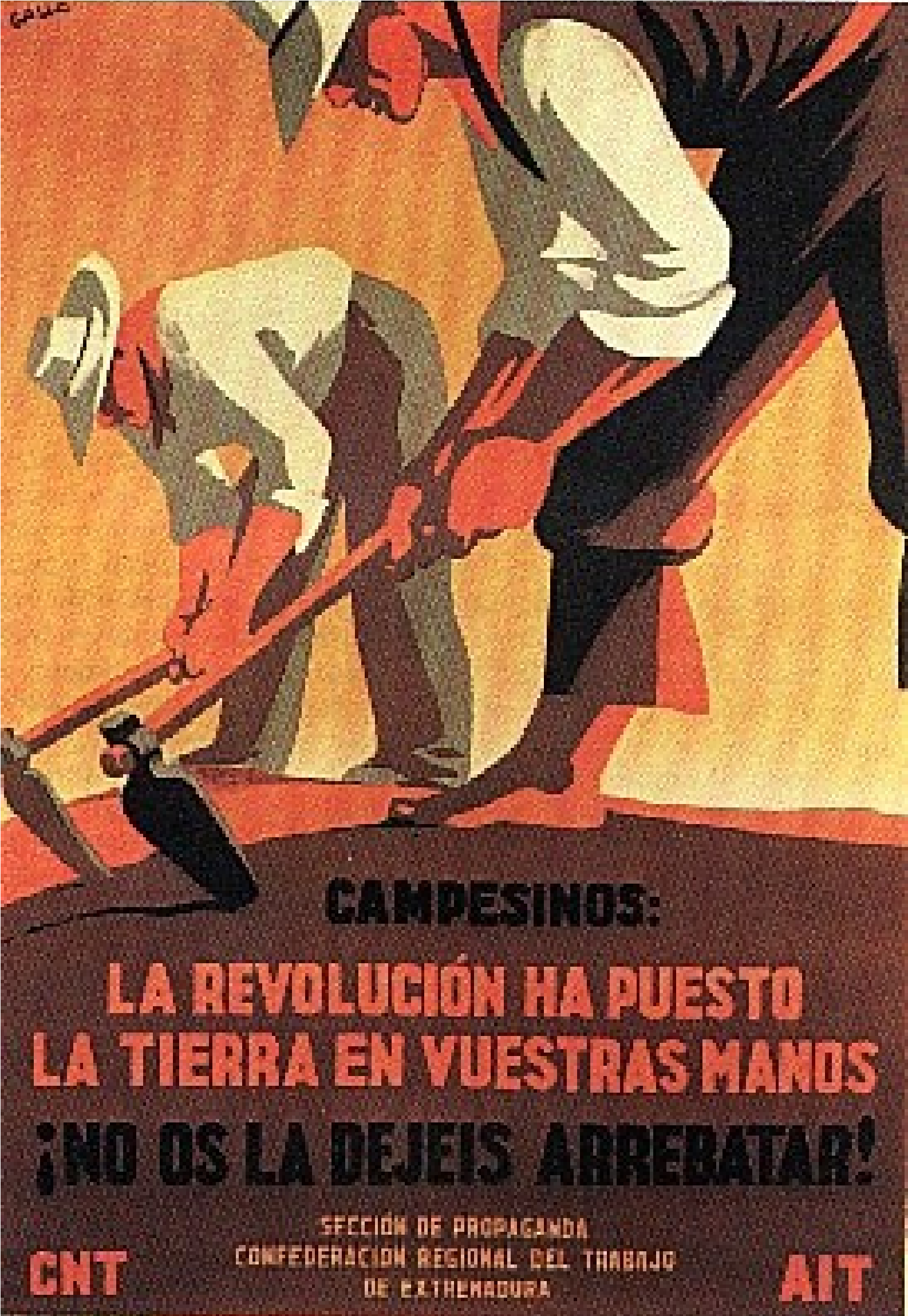

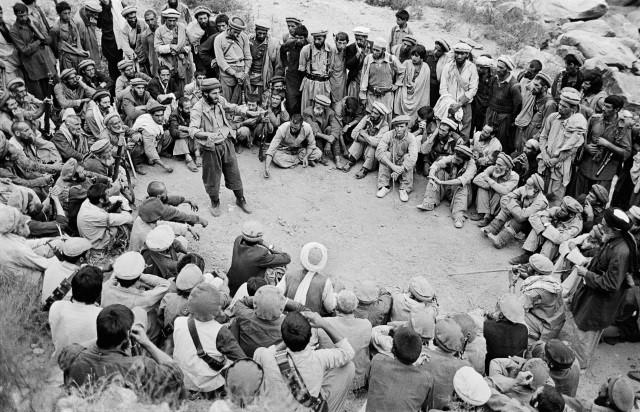

“When Franco and his fascist generals attacked the newly elected Republic in July 1936, thousands of industrial workers and peasants responded with militias and also with a massive collectivization of land, factories, transportation systems, and public services. Collectivization encompassed more than one-half of the total land area of Republican Spain, affecting the lives of nearly eight million people. Large cities like Barcelona were transformed into federations of neighborhoods, while in many parts of the Republican held countryside, new irrigation systems and well-organized federations of communes allowed peasants to bring new land under cultivation, expanding and diversifying production. Social landscapes accommodated new educational, cultural, and health facilities. Massive regional exchange networks formed by federations of collectives starting at the local level and working their way up to districts and provinces, linked cities with the countryside for the purposes of distribution and consumption, extending transportation and health services into areas that had never been serviced before. A revolution, which began by creating more communal and egalitarian relationships among people, resulted in the creation of highly efficient and environmentally sensitive new spatial formations.” (Breitbait, 2009)

1 Introduction

1.1 What is environmental in anarchist approaches to space?

In the 1930s, during the Spanish Republic, the revolution led by industrial workers and peasants was controlling the land on which 8 million people lived, worked and were fed at the time. This large scale social experiment inspired by anarchist ideas had its environmental implications. These implications are well summarized by Breitbart (2009) who concluded that the Republic did not impose on villages and neighbourhoods to become self-sufficient entities, neither in terms of goods and trade, neither in food, housing and other essential provisions. Instead, the councils anticipated a developed and complex spatial relations framed by the economy of everyday consumption and production that propelled regional exchange and local cooperation. In these relationships the city became interrelated with the rural towns and villages, large scale collectivization attempted to integrate industrial and agricultural production. At the same time, the peasant and citizen are seen as active subjects of the integration — both contributing to progress with their manual and intellectual labour in gardens, workshops and local councils. This historical example is one of many everyday lived practices in which environment, politics and urbanism converged into an alternative experience in (re)production of space as inherent to Nature. These experiences are part of the history of ecological urbanism that continuously seeks to oppose expanding urbanization with holistic and integrated visions of human and non-human life embedded in sustainable urban processes. Many of these experiences were inspired, observed and documented within the community of anarchist geographers and urbanists. Until now not that many dialogues on ecological urbanism took into consideration the history of anarchist inputs to the idea. This particular work attempts to bring two points in this direction: a) ‘conscious practices of anarchism’ (as Malatesta defines the history of anarchism) share a common environmental approach and b) there is a continuous thread of decentralist inputs to ecological urbanism that flows between the pre- and post- World War Two period. Both points aim to illustrate the from-below approaches to ecological urbanism as methodologically and practically relevant for the future of the field.

Methodology

The works of two prominent figures of anarchism and (urban) geography, Peter Kropotkin and Colin Ward are compared to build the argument presented in the previous chapter. Instead of entering the complex study of historical practices or attempting to give an overview of anarchism shaped work on ecological urbanism, the thesis uses the observations of two giants of decentralist thought and their observations on people’s relation to the environment. One geographer and one architect, dedicated significant volumes of work and time to observing the practices of production of urban space, describing and speculating about them from the anarchist perspective. The methodological hypothesis is that literature written by both authors is sufficiently intertwined to be read as a) time-wise continuous thread of socio-political thought on ecological urbanism and are b) material that inspired concrete practices relevant to an ecological urbanism.

These two figures have a pivotal role, not in defining what ‘anarchist’ means in the context of ecological urbanism or how anarchist paradigms relate to ‘environment’, since, as Ferretti (2019) recognizes, there is no just one uniform ‘anarchist’ approach to anything, including space and ecology. Instead, their work interconnects the lived experiences, utopian speculations and critiques of the State and capitalism and as a result, is fixing together a distinct reading of (urban) space. These two authors also connect two centuries of what we call ‘modern’ anarchism, the same period in which the urbanism increasingly acknowledged the urgencies of negative environmental impact — to which it responded with a quest for the ecological urbanism and rethinking the (urban) economy around resource management (Springer, 2013) □ . The temporal coincidence of the two movement makes the distinct anarchist vision for ecological urbanism worth considering. It is interesting to consider how — mutual aid, cooperation, do-it-yourself and direct action ethics, and non-hierarchical emancipatory tools — work when incorporated in the framework of urban planning.

The thesis uses primary sources from both authors, their books, articles in periodicals and secondary researches of interpretation as sources for qualitative comparison of two authors and their contribution to this discussion. The comparison of the literature extracts on the first level similarities in their conceptions and observations concerning the ecological urbanism. On the second level method draws the differences between the authors and contextualises them. The third level uses the literature review to relate conceptual work by authors to cases in which it was put in practice and examples to which they refer.

The presentation of results takes the form of printable publication. It is based on three parts: 1) Introduction in which existing literature on the history of proto-ecologist, regionalist and anarchist geography are used to explain motivation, relevance, aim and methodology, then 2) presentation of the body of work by compared authors in which authors are independently presented with an introductory chapter summarizing their biography and key ideas and three chapters that are built around three key groups of works by the authors. The final part is 3) the Dialogue in which the two authors are confronted in the form of fictional conversation. The last chapter presents the thread of anarchist inputs for ecological urbanism frankly and opens the discussion to possible implications of the research.

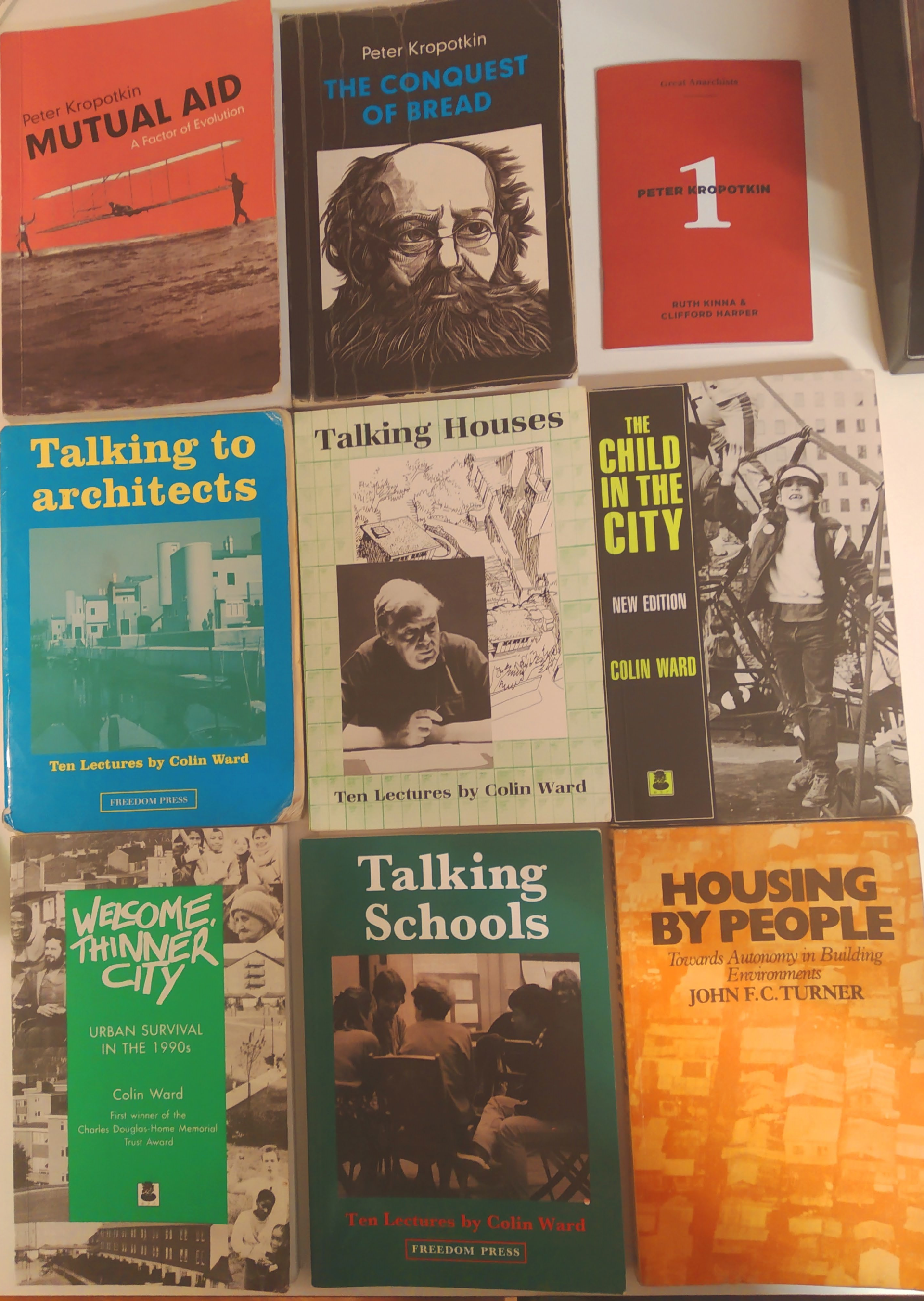

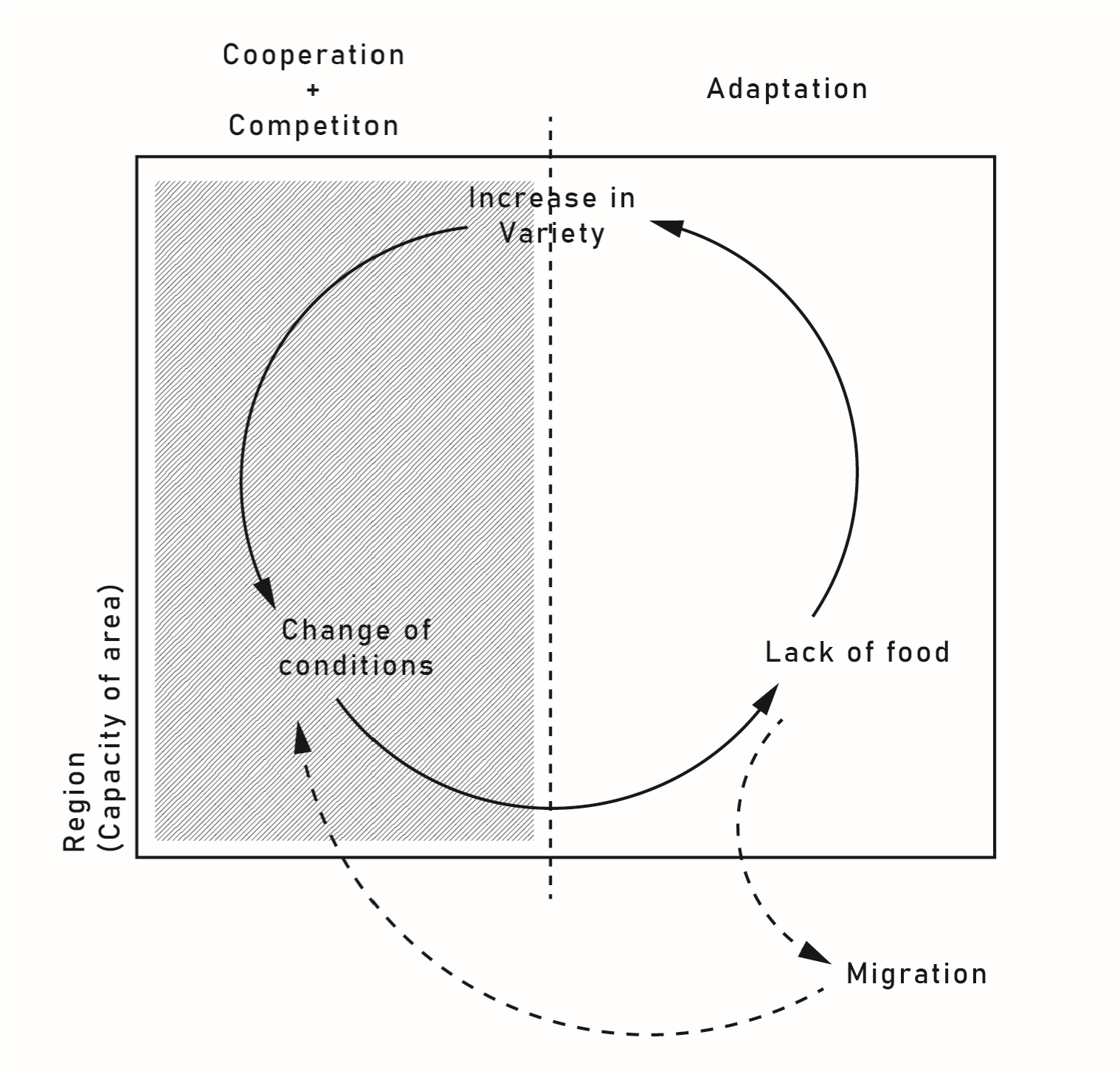

Source: author

1.2 ‘The anarchist thread’ in ecological urbanism(s) — Historical overview

In the following paragraph, the brief history of “the anarchist roots of the planning movement” settles the two authors in the legacy of ecological urbanism. The “anarchist roots” are acknowledged among the historians of urbanism due to Peter Hall’s classic book Cities of Tomorrow, published in 1988, as one of the most comprehensive overviews of the history of urban planning. Hall writes that the urban planning movement “arose from the anarchist movement, which flourished in the last decades of the 19th century and the first years of the 20th century. That is true for Howard, for Geddes and for the Regional Planning Association of America, as well as for many derivatives in the European continent” (Hall, 2014). Another key idea of anarchism’s influence that Hall recognises is the notion of bottom-up urbanism. Built forms of cities should, writes Hall, “come from the hands of their own citizens; that we should reject the tradition whereby large organisations, private or public, build for people and instead embrace the notion that people should build for themselves. We can find this notion powerfully present in the anarchist thinking (...), and in particular in Geddesian notions of piecemeal urban rehabilitation between 1885 and 1920 (...) It resurfaces to provide a major, even a dominant, ideology of planning in third-world cities through the work of John Turner — himself drawing directly from anarchist thinking — in Latin America during the 1960s” (Hall, 2014).

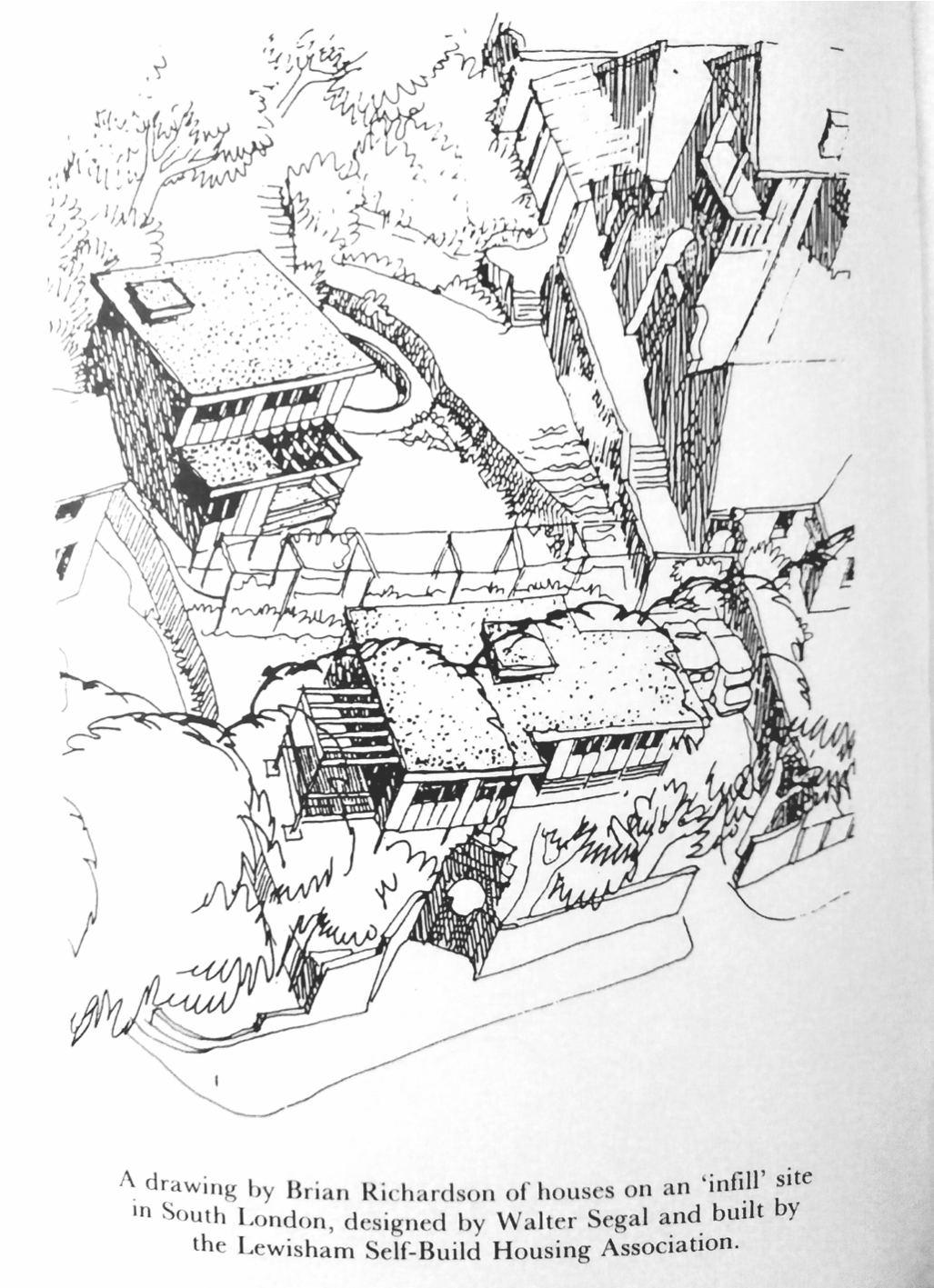

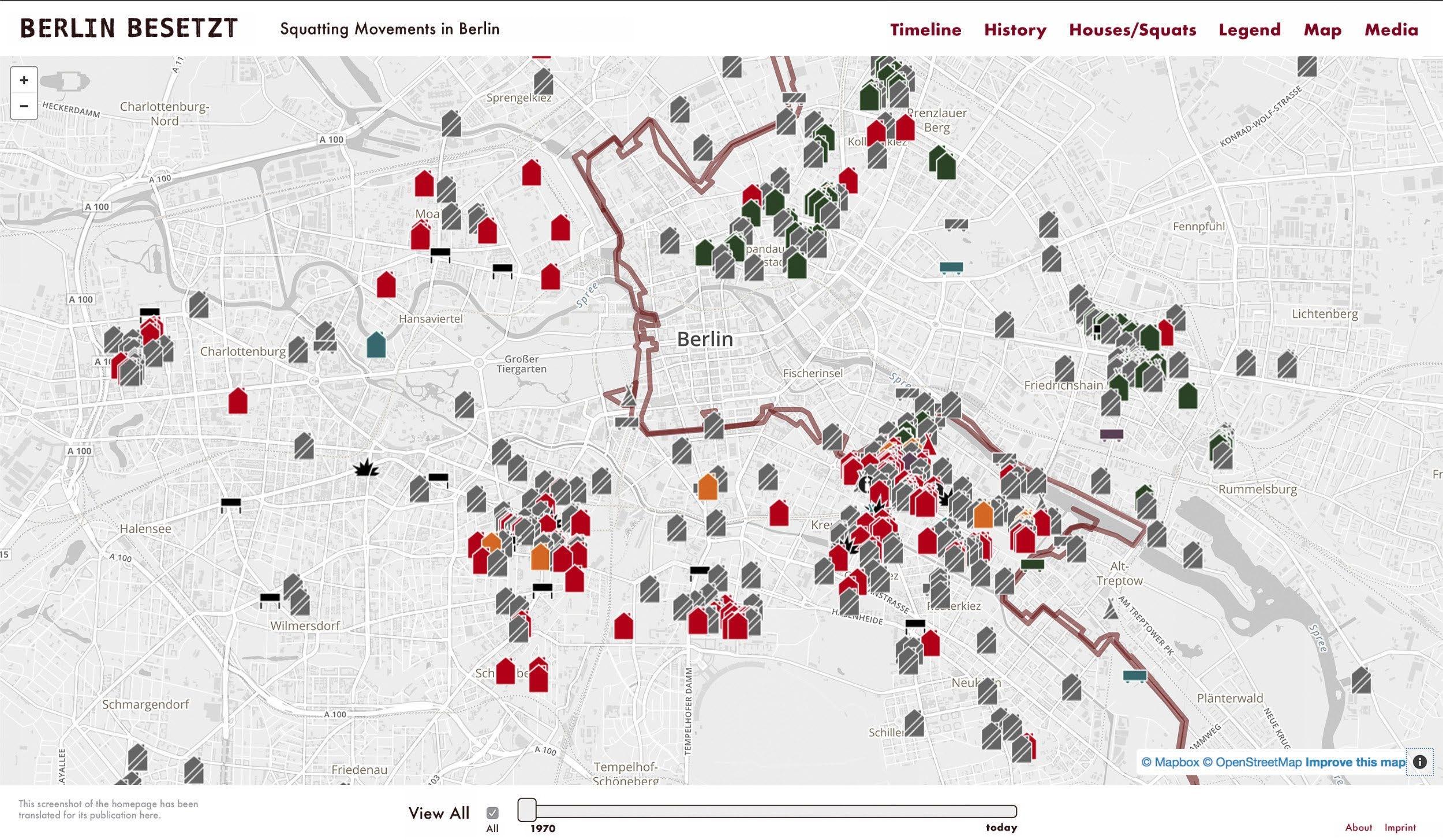

Anarchist approach to urbanism can be traced as a continuous thread through the change centuries through connections between Reclus and Patrick Geddes and Kropotkin and Lewis Mumford. All for of them presenting a stream of regionalist thinking within dominantly ,urban‘ and statist thread of geography in the observed period. Geddes and Mumford will later be an inspiration for the Ward’s and John F. Turner’s concept on dweller’s control in urban planning. In the period following the World War 2, the bottom-up urbanism became a common issue for anarchist architects and urban planners like Colin Ward, Giancarlo De Carlo, Carlo Doglio, Walter Segal etc., as well as for poor and landless people all around the world. Overseas, the influence reached to American anarchists like the Goodmans and Murray Bookchin whose ideas of municipalism, democratic federalism and ecological urbanism echo to our times. Many practical examples of self-help housing, squatted camps, build-it-yourself construction models, self-organised communities are realised by people disappointed with the inability of the State institutions or market to provide affordable and safe housing. As a response, they seek ways to provide housing under their own terms. This rich history in radical housing practices is a seedbed for what later diversified into similar experiences that established bottom-up social and cultural institutions, provided food through communal gardens and solidarity networks, initiated selforganised schools and care facilities, run citizens’ campaigns, syndicalist actions and rent strikes etc. In the seventies during the economic and oil reserves crisis, the birth of large scale environmental movements was founded on the capacity of social movements to mobilise, organise and consolidate people on different scales of territory directly inspired by writings and experiences of the pioneers before them. This continued until the end of the century in the form of the anti-globalisation movement and its’ critique of neo-liberal politics, growth-driven development, and global inequality. It is hard to encompass the whole spectrum of a cooperative, self-help and direct action based practices in producing housing, services and goods in neighbourhoods and towns in Latin America, Asia, Europe and almost every corner of inhabited Earth. It is even harder to merit the impact these practices had on social and environmental justice throughout centuries and geographies.

However, the following paragraph will try to summarise authors who made an influence on both, history of ideas and production of experiences in ecological urbanism and who could be credited as an anarchist. In his account on the historical interconnection between anarchism and geography (Springer, 2016) stated that early anarchists geographers were proto-ecological because their ideas challenged occidental philosophical tradition that “ put humans at the top of the naturalistic hierarchies, by anticipating present-day relational ideas on hybridity, more-than-human interaction and even affectivity.” (Ferretti, 2019). First relevant body of work to reawaken this continuous thread is the collection of writings, references and relationship between primary authors and figures of the field. The reconstruction of this thread wants to remind and revalue the anarchist tradition in planning history, its ideas and forms of city intervention. This thread is an almost forgotten tradition when, paradoxically, notions of space and urbanism resurging today have a cleat connection with these old ideas (i.e. new rural-urban relations, creation of spaces from below, notions of relational and relative space against absolute Statist space). Unlike the Marxist branch of socialism, anarchism was deeply marked by spatial imagination from the moment of its affirmation in the socialist movement in the mid 19th century. It might be so because some of its most significant thinkers and figures, Reclus and Kropotkin, were involved in spatial disciplines such as geography. This relationship inspired an active exchange between two worlds: one of ideas, academia and scholarship, and one of the experiences, practice and action. Reclus and Kropotkin, the anarchist geographers, have been remembered by Peter Hall’s Cities of Tomorrow as having a fundamental influence on Geddes and Mumford’s regionalist ideas of the first third of the twentieth century. Simultaneously on the turn of the centuries, they inspired an array of social movements in European and global cities primarily engaged with spatial issues such as housing and consumption strikes. These chronological highlights point out the key ideas, experiences and figures of the history of anarchist thought on cities and their surrounding in their respected context. Aware of many unnamed authors and efforts that enabled the continuity of this tradition and limited by the format of the thesis, the following paragraph presents just a short overview. The overview will provide an account based on published research on Reclus and Turner by Oyon and author’s research in progress on other anarchist experiences.

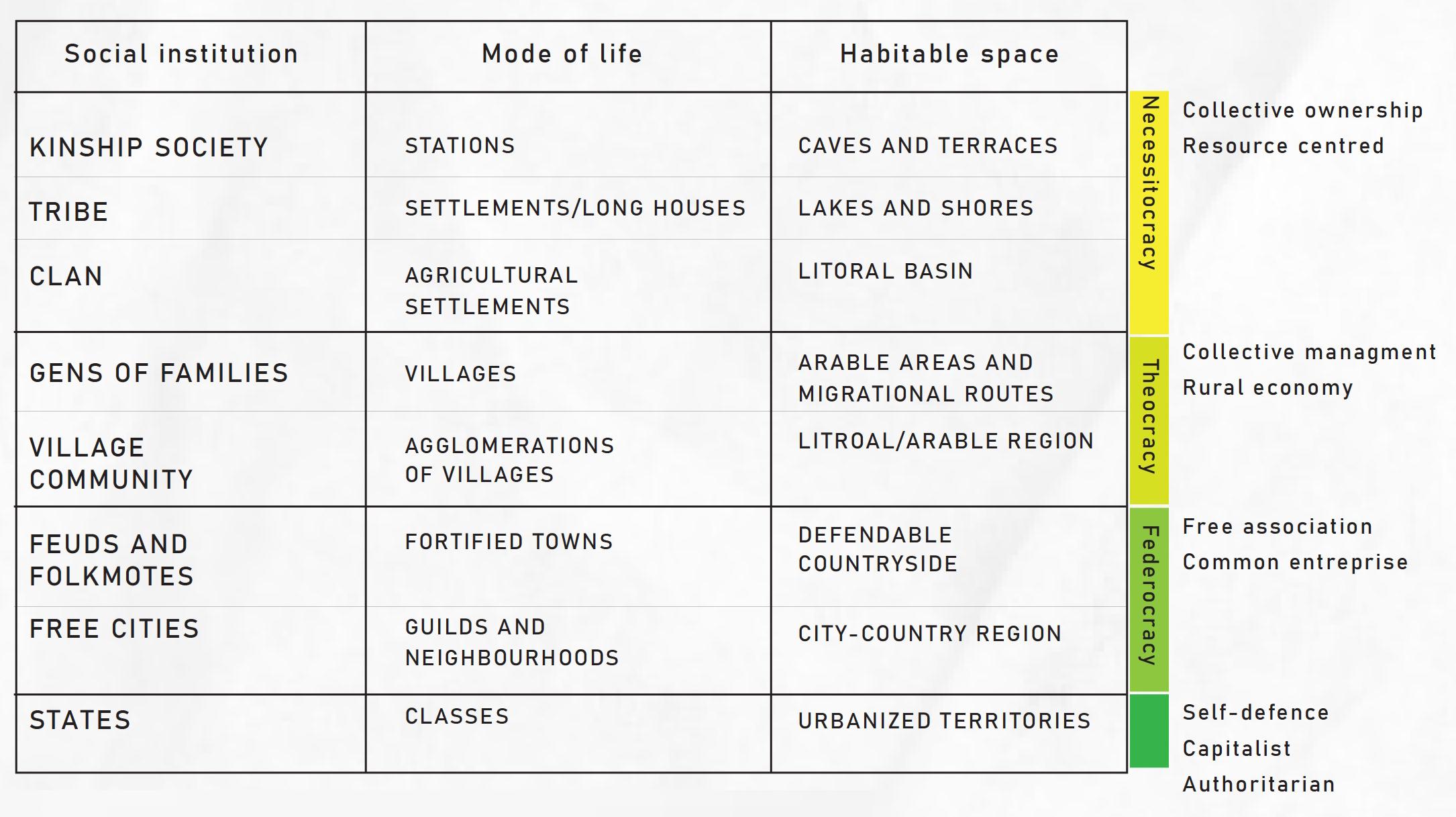

Source: authors

1.2.1 Production of ideas: The anarchist geographers, 1866–1899

Reclus and the nature-city fusion

Elisee Reclus in the second half of the 19th century writes primarily about a fusion of nature with a city that expands indefinitely through its countryside encompassing the regional dimension of urban and rural at the same time. Since his early writings in the 1860s, he explores the city as a concentration of natural capital. Cities, as he describes, are born and grow based on their natural advantages and their immediate natural region amplifies their growth. The future Reclusian city is an unlimited city, ‘the indefinite extension of the city in total fusion with the countryside’ interconnected through periurban spaces of cultivated nature-fields, orchards, gardens, together with the technical infrastructure that allows the city to have a life as an organism — water infrastructure, transportation, food supply. Therefore he imagines a) railways and roads as a key to achieving the nature-city fusion, b) the suburbs imagined as settlements of houses integrated with nature, without fences to separate their inhabitants, pivoting around sub-centres with large parks and public services. His ideal approach to nature-city fusion is grounded in his belief in ‘le sentiment de nature’. In other words, that every person beholds a profound potential for changing the course of urbanization away from unhealthy densification and centralization. For this Reclus is considered proto-ecological urbanist whose influence can be traced to these days.

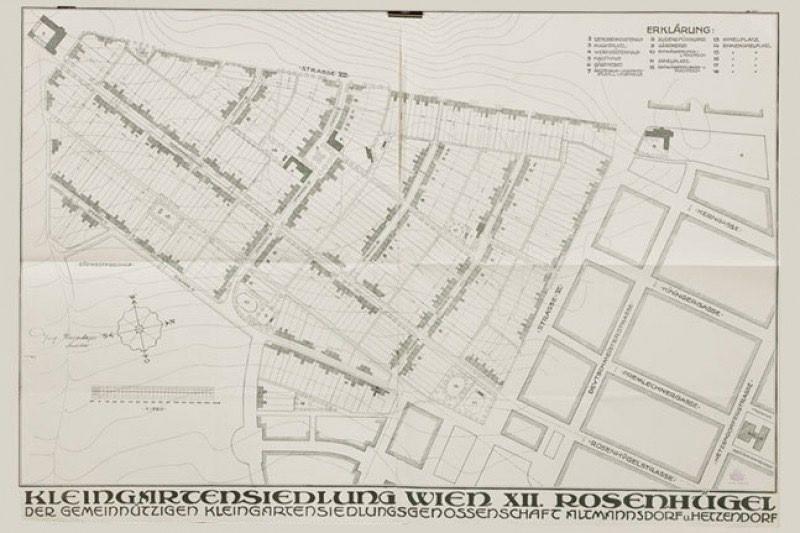

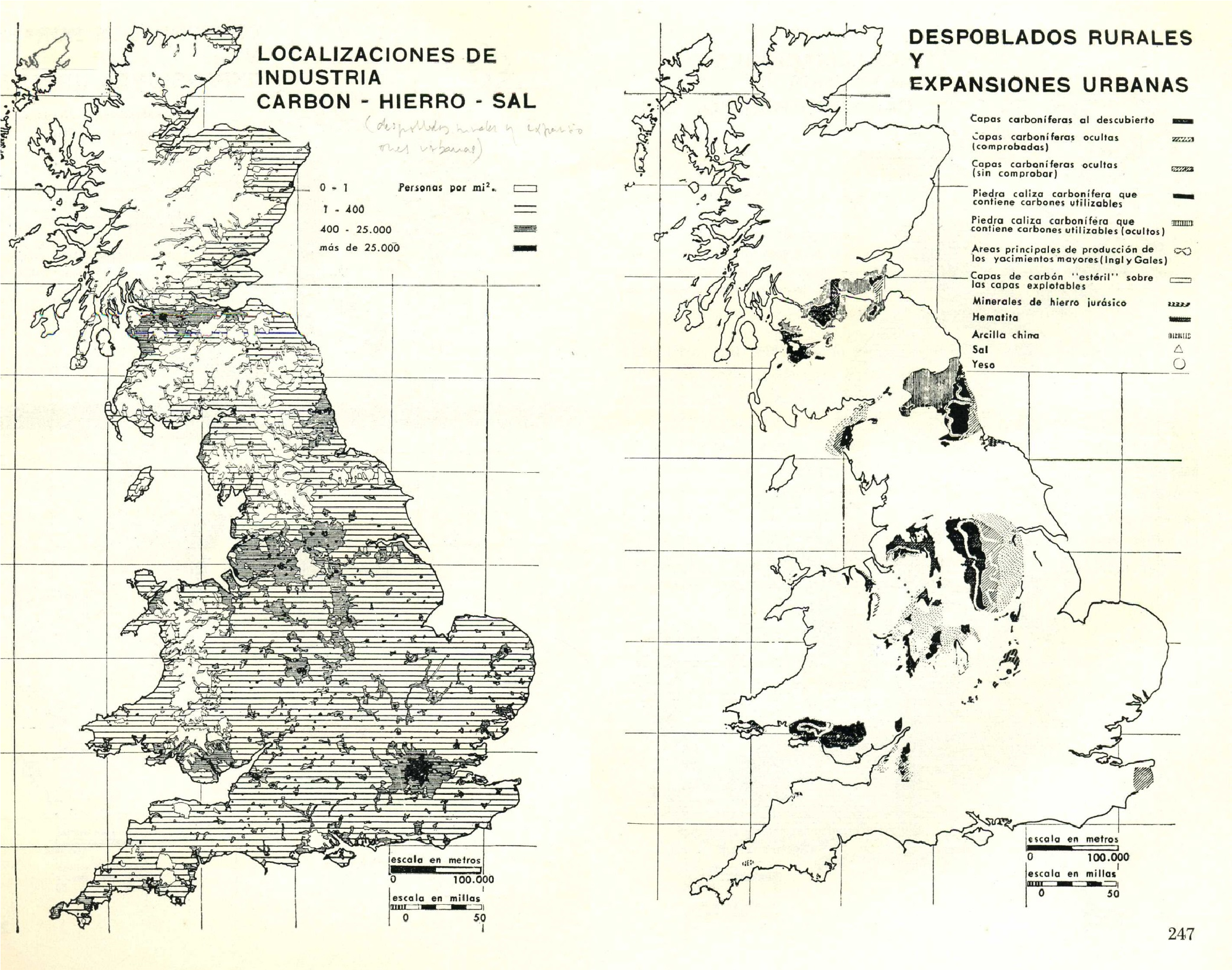

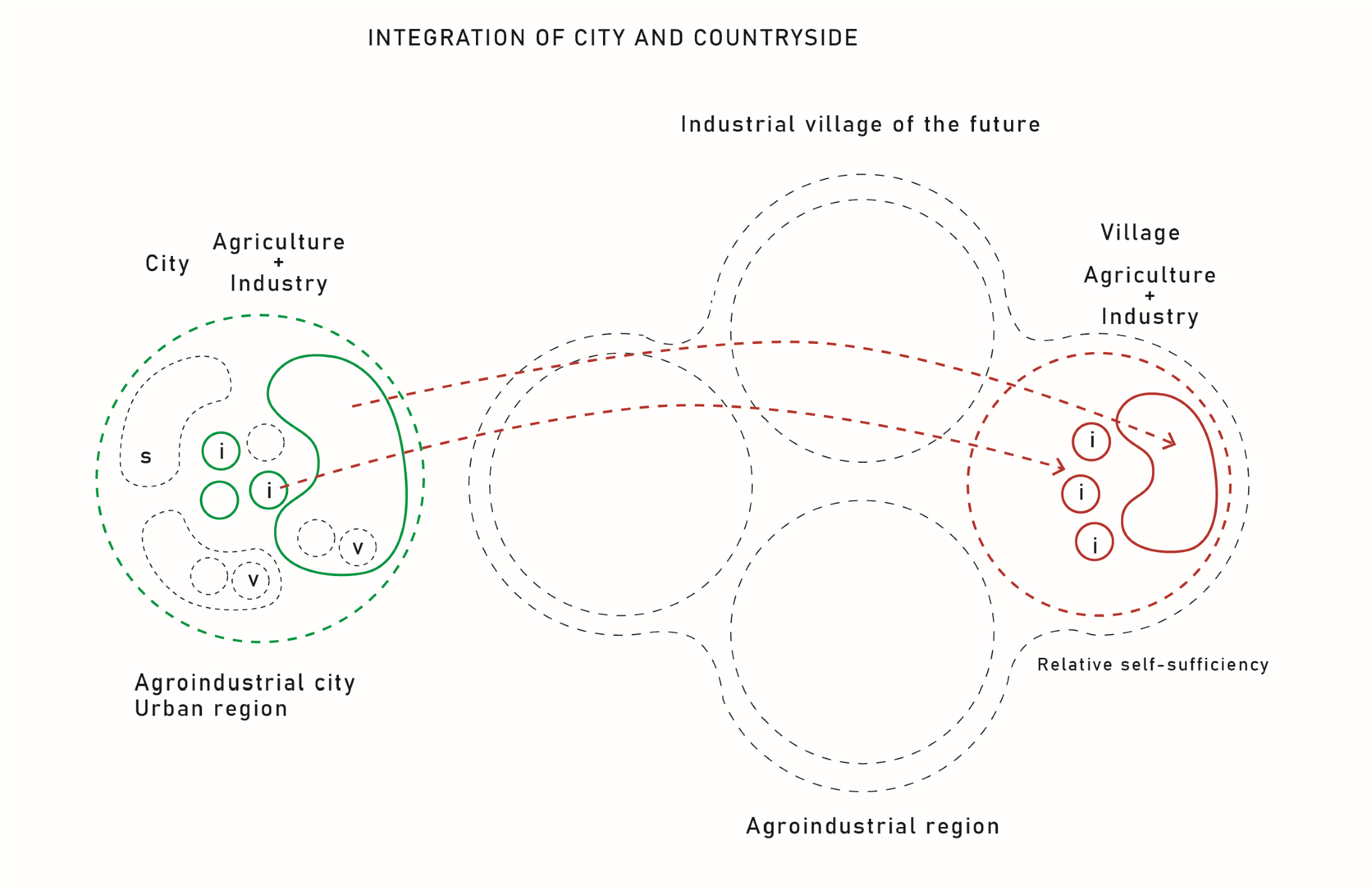

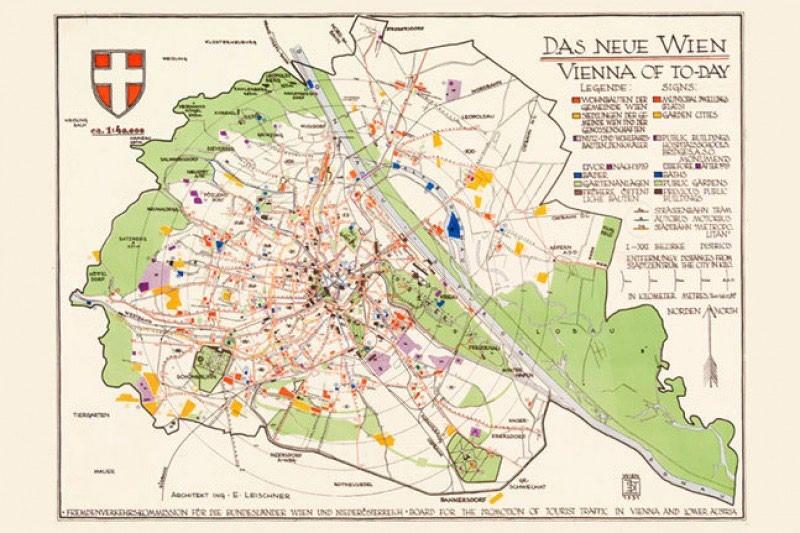

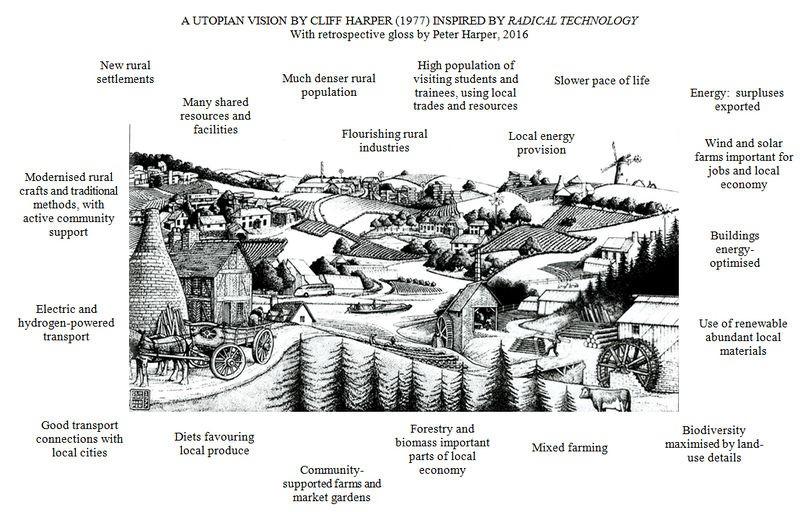

Kropotkin and the countryside-city economic integration

Since the decade of 1880, Kropotkin developed an idea of the economic integration of the city and countryside. He imagined it as a territory where the big city and its surrounding fields with decentralized and industrialized, relatively self-sufficient, communities reciprocally feed each other with food, goods and primary resources. The inhabitants of such integrated spatial system are both workers and farmers, producers and consumers of their agricultural and industrial products. Although the idea is presented in his seminal Fields, factories and workshops (1899), Kropotkin’s book The Conquest of Bread (1892), as a collection of preceding ideas on how to organize the post-revolutionary society became the book that inspired the anarchist labour movement in Spain during the first decades of the last century. In these two works, he conceptualizes post-revolutionary reorganization and (self-) management of the city through socialized consumption established to provide basic needs ahead of restarting the production after the revolution successes. The new emancipated society he advocates is set in a new space that revolutionizes the capitalist conception of food supply, housing and municipal public services.

1.2.2. The production of experiences, 1899–1939

Reclus and Kropotkin’s thinking influenced two different forms of action in two different contexts. First, in the Anglo-Saxon area, where their urban and territorial thinking was present in the work of regionalists Geddes and Mumford. The second space of influences was the rich imaginary of territorial planning projects that sprouted from the libertarian world during the Second Republic in Spain and its more or less direct affiliation with the territorial reflections of Kropotkin.

The regionalist bridge

In the works of Geddes and Mumford, we find various elements that connect with ideas of the anarchist geographers. The influence in Reclus on Geddes and even more of Kropotkin on Mumford are evident. The Reclusian call for a city in harmony with nature and his region is present in the development of Geddes’s ideas on the region-city, the Valley Section, and his Outlook Tower in Edinburgh. Mumford’s regionalism and the projects of the Regional Planning Association of America during the 1920s and 1930s are inspired by the ideas of decentralization from Kropotkin and especially Howard’s city-garden. Both Geddes and Mumford will later mark out the generation of European anarchist architects and urban planners from the postwar period creating an undeniable link bridge with the old tradition of 19th-century anarchist geographers, particularly with Kropotkin.

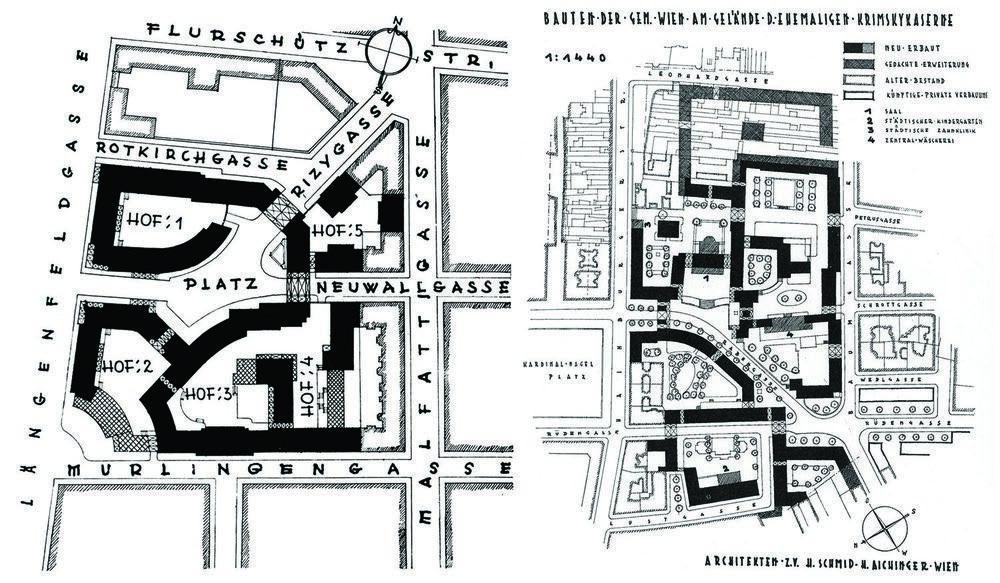

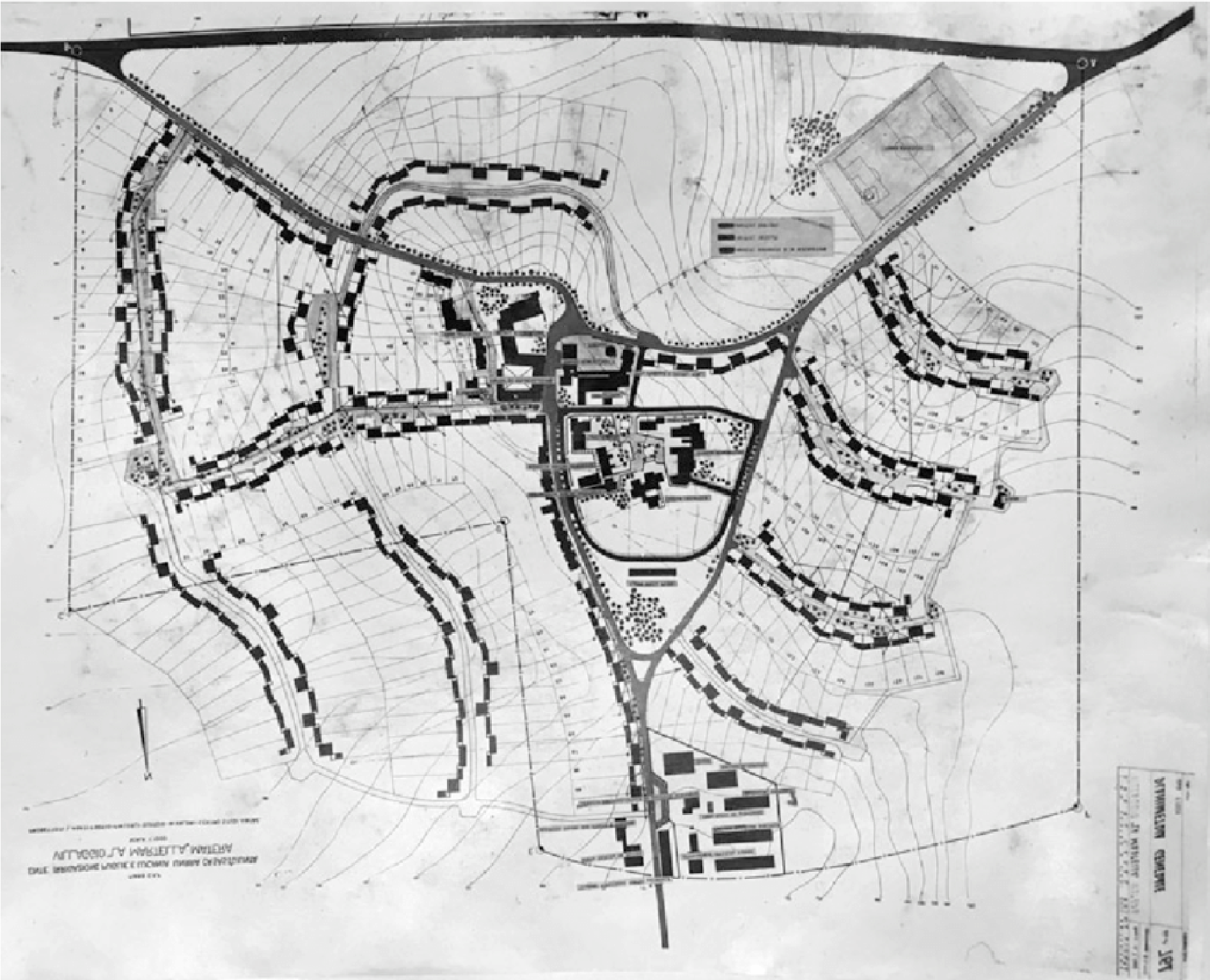

The proposals for the agro-industrial symbiosis of the Spanish libertarians

From the self-sufficient communalism of Urales to the anarcho-syndicalist writings of Besnard or the diverse territorial models of Isaac Puente, Gaston Leval, Abad de Santillan, Martmez Rizo and Higinio Noja there was a rich world of ideas of spatial imagination of libertarian communism intended to unfold with the social revolution. Masjuan Bracons (2000), reduces these ideas to an anarcho-communalist and anarcho-syndicalist tendencies, with essential coincidences: a) the organization from below of municipalities and communes into federations of municipalities and, especially, b) the imperative of decentralization of the big cities towards a ‘stable synthesis between the countryside and the city’. The later’s potential is confirmed by recognition of the Congress of the 1936 CNT Zaragoza Congress. Nothing came closer to the essence of the territorial message of Kropotkin than those envisioning of ‘agro-industrial symbiosis’ in Republican Spain.

The experiences of direct action

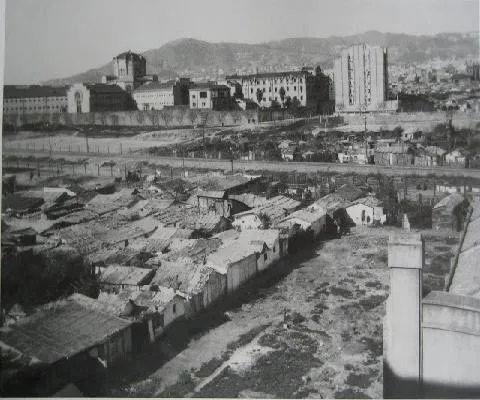

The tactics of direct action emerged from anarcho-syndicalism and dispersed throughout the world during the early 20th century (i.e. tenant strikes at the end of World War I: France, Spain, Argentina, Mexico,...). In Spain CNT’s rent strikes in the summer of 1931 were followed by interventions on the housing market ahead of the Civil War. Since the dawn of Spanish anarcho-syndicalism, the anarchist social organization rests on a functioning system from below with the workers federation as a model intended to extend to the entire social organization. Spanish anarchist embodied the Kropotkin’s ideas on the organization from below in a municipal setting through direct action.

Source: https://prouespeculacio.org

Source: https://prouespeculacio.org

Source: flickr of CGT Andalucia

1.2.3. Urbanism from below: the anarchist architects of the second post-war period, 1939–1976

“The anarchist reflection on the city in the second post-war period for the first time reaches architects and urban planners. In this, the generation architect and planner Colin Ward is the editor of the Freedom magazine, established by Kropotkin, and Giancarlo de Carlo and Carlo Doglio in Italy are contributors. The line of reflection on urbanism from below also influences the American anarchists of the fifties and sixties like the Goodmans and, with an emerging ecological municipalist nuance, Murray Bookchin. The autonomous direct action becomes a driving principle of the ‘anarchist solutions’: “In the face of capitalism, we must not wait for the great revolution that will change everything. The practices of freedom are for today. They are daily actions of existing revolution, that of the here and now. They are ‘anarchism in action’” (Ward, 1973)

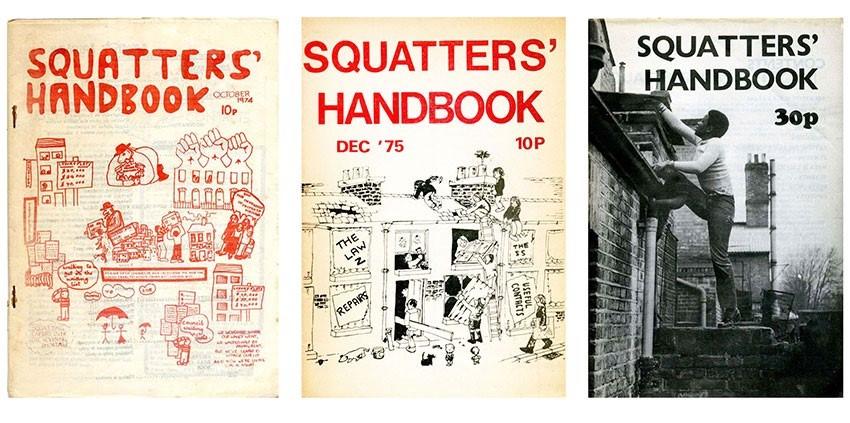

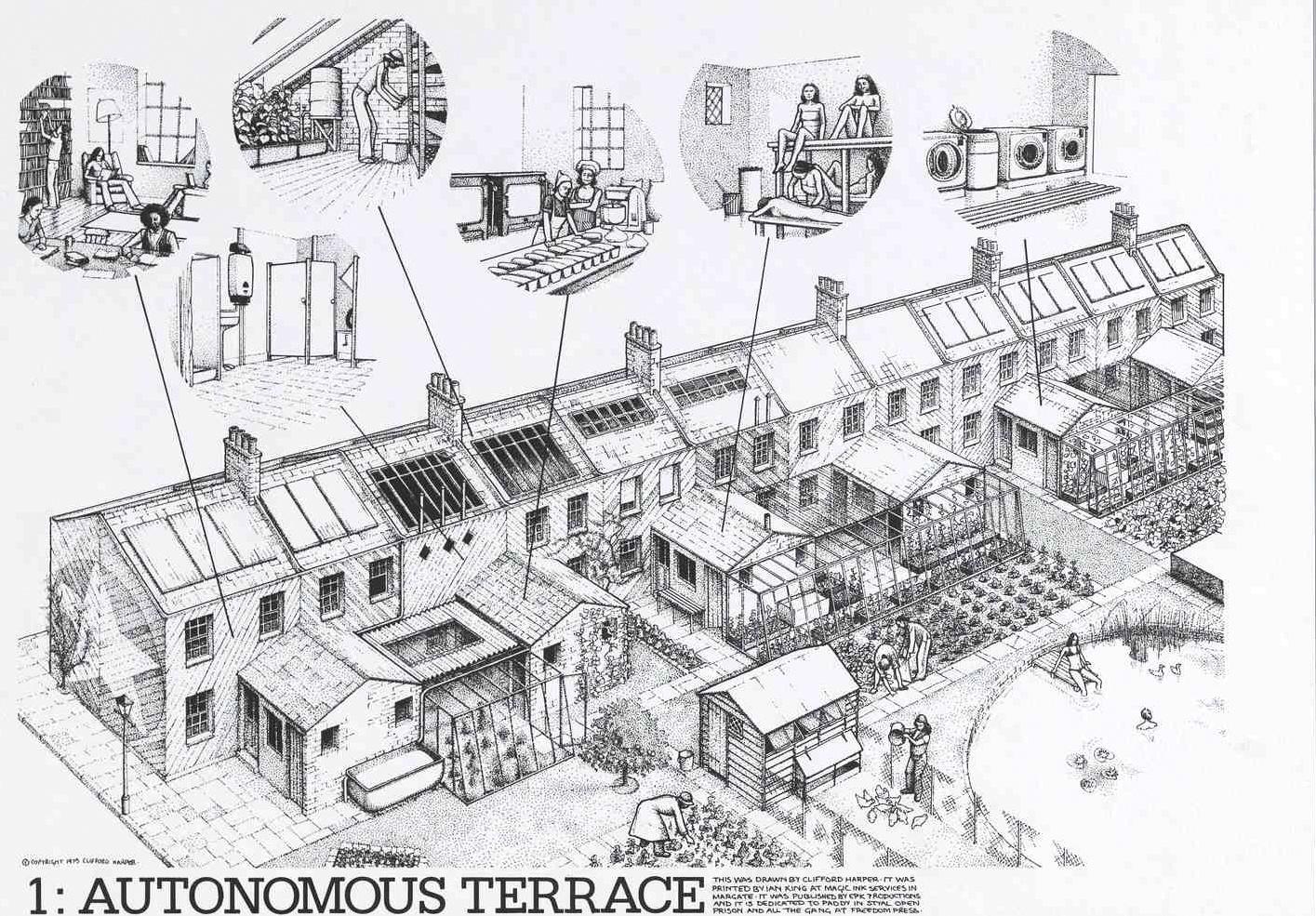

Colin Ward and direct action in housing

Colin Ward was a productive writer and practitioner that developed his first interest in self-help housing with post-war squatters in 1946 and occupations of abandoned military camps (a practice that included 40,000 families in England and 5000 in Scotland). He afterwards developed a critique of the large-scale management and massive bureaucracy of state-owned/municipal housing estates. He as occupied by the forms of housing production, tenure and distribution but engaged in other topics as well: Tenants Association Cooperatives and the concept of property (Tenants take over, Vandalism), the self-construction (Housing: an anarchist approach), anti-plan and participatory planning from below (Talking houses, Talking to Architects), uses and appropriations of public services and spaces (Talking schools, Exploding schools, The child and the city, Bulletin for Environmental studies addressing teachers) and ecology (articles in Freedom). He appropriated Kropotkin’s ideas on the integration of production and consumption, especially in the context of housing and community self-management and created a more complex set of proposals inspired by the real experiences of both pre and post-war Britain.

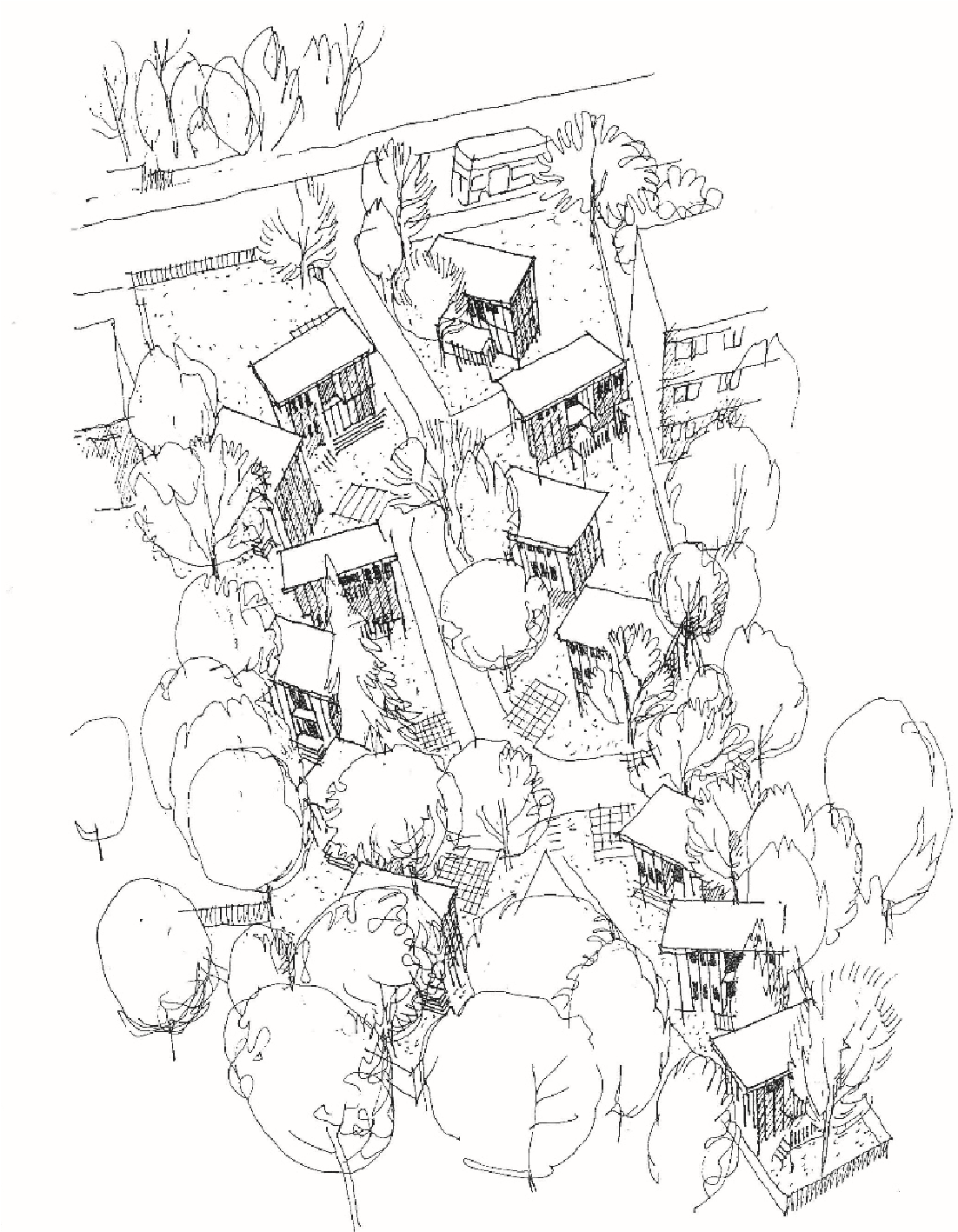

Giancarlo De Carlo: the architecture and urbanism of participation

Giancarlo De Carlo was an Italian architect with anarchist background explicit since his early writings in journals as Freedom and Volonta. He dedicated himself to the participation of users in the construction of housing mediated by architects. Recognizing that all three phases of the architectural project (the definition of the problem, the elaboration of the building solution and the evaluation of the results) require the presence of the users he writes: “The practice of participation changes each phase and the system of relations between them(...)the architectural conception becomes a process”. The means to achieve the goal are what matters for anarchist architecture and urbanism: “the architecture must be removed from the architects and devoured to the people who use it”(De Carlo, 1972). His most noted works were along these lines in San Giuliano’s in Rimini and the Matteotti neighbourhood in Terni between 1969–1974, and the Urbino plan with the application of indirect participation. De Carlo works, and thinking has to been seen in connections with Carlo Doglio writings and regional planning initiatives in the post-war Italian south.

Source: https://rastrosderostros.files.wordpress.com

Source: Jose Luis Oyon

John F. C. Turner: Housing and the neighbourhood made by users.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Turner created an engaged and open vision of self-help housing. Self-help housing neighbourhoods made by users over time were not finished and serialized object, but as a progressive process where the inhabitants both decide and execute their ideas. Since his first work in Architectural Design in 1963 about new housing solutions in Latin American countries, Turner’s main concern has been to give visibility to the heterodox process of creating self-built neighbourhoods in at the time called ‘underdeveloped countries’. Based on practical experiences, he describes the value and benefits of autonomy of the self-built housing for its users. Turner’s vision is also a renewed subsequent turn to the Kropotkinian vision since it does not base on the simple reproductive ‘satisfaction’ of the needs of food, housing and clothing. Instead, it recognizes emancipatory power in socialized consumption of the meaning of housing in its complex socio-economic relation: Housing not as an object but ‘as a verb’ — or direct action.

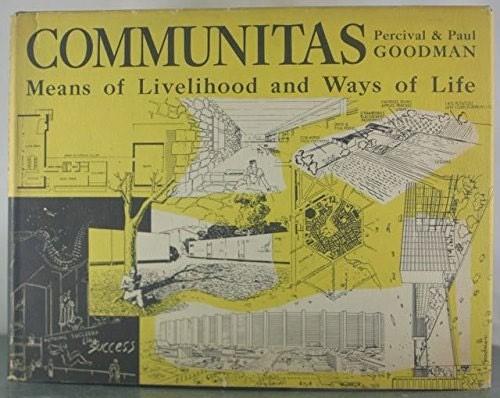

Anarchist urbanism ideas in the USA — Bookchin and Democratic federalism

In the post-war USA, two brothers became the bearers of anarchist ideas in the context of urban planning. Paul and Percival Goodman took further decentralist concepts of Peter Kropotkin and explicitly discussed them in their groundbreaking book, Communitas: Means of Livelihood and Ways of Life (1947). The book consists of ‘A manual of modern plans’ reviewing the conceptual history of twentieth-century planning and ‘Three community paradigm’, a series of hypothetical community planning schemes centred around communality proposing answers to the central question of the book: ‘How to find the right relations between means and ends?’ “Encouraging people to reject externally imposed designs for living, the Goodmans echoed Kropotkin’s call for people to transform themselves into active change agents and to decentralize decision making in planning wherever and whenever possible” (Breitbait, 2009).

On the end of the century, two other prominent figures propelled the anarchist ideas in the USA writing about space, territory and relation of politics and environment. Hakim Bey’s influential book Temporary autonomous zones (TAZs) recognized both historical and contemporary tactics of shortterm, spontaneous and festive ruptures the inhomogeneous fabric of capitalist space and time as political acts that encourage free expression, radical pedagogy and liberation. His works arise from Situationist International and post-modern anarchist thinking. Although not as comprehensive as Goodmans, Bey’s contribution is significant in recognizing in parallel autonomy (free association and dissociation) and temporariness (awareness of the authoritarian character of permanent) as a ground for enabling empowering processes in space.

The second figure is much more relevant in the context of environmentalism and urban planning. Murray Bookchin has taken much from Kropotkin for his theory of social ecology and municipal democracy. The rich body of work he created covers an array of topics from urbanization, social theory, environmentalism, system theories, Spanish Civil War etc. He pioneered or preconceived several social and ecological movements like environmentalism, Deep ecology, degrowth movement etc. However, his proposals are often disregarded as politically overly rigid, impossible and radical. These claims miss his probably most relevant contribution. Bookchin developed the concept of libertarian municipalism, a form of a federative, stateless and democratic political system. Egalitarian and direct action principles of anarchism combine with the ecological and regionalist concept of local governance and resource management based on a municipal scale of free association. During his time in prison, Abdullah Ocalan, Kurdish leader of Marxist-Leninist party read works of Bookchin and other post-Marxist authors and found inspiration in their communalist ideas. A big turn in Kurdish ideological consensus on ecological and feminist objectives and shift towards stateless territorial conception that they call ‘ Democratic confederalism’ is directly inspired by writings of Murray Bookchin. Murray Bookchin died in 2006.

Renaissance of academic interest in anarchist geography at the change of the centuries

The role of anarchist thought in early geography had a period of larger and smaller acceptance usually connected to an interest in ‘fathers of anarchism’ by different social and anti-capitalist movements like in the 1970s and late 1990s (Springer, 2013). The most recent revaluation of ‘The anarchist roots of geography’ in academic circles is two decades old ((Schwartz et al., 2004; White and Kossoff, 2012; Ferretti 2011, 2013; Pelletier, 2013; Araujo et al. 2017; Springer, 2016; Ruth 2016; McLaughlin, 2017). From the perspective of urban planning, the focus is on practical experiences that flourished all around the world from the bottom-up and direct action engagements of citizens and peasants, daily live practices and local scale surges. More attention is given to “the cooperative movement; DIYskills and small-scale mutual aid groups, networks, and initiatives; as tenants’ associations, trade unions, and credit unions; online through peer-to-peer file-among neighbourhoods as autonomous migrant support networks and radical social centres; and more generally within the here and now of everyday life” (Springer, 2013).

On the other hand, the larger scale is covered by the works of Anthony Ince, Geronimo Barrera de la Torre, Federico Ferretti and many others who, by considering different implications of nonstatist geography, opened space for introducing indigenous, de-colonial, ecofeminist and non-human narratives in urban planning. I do not have an intention to encompass the whole scope of recent horizons of anarchist geography, and it’s potential within ecological urbanism. Instead, I will conclude that due to their work that highlights numerous constructive practices across the world, anarchists managed to maintain throughout the 20th century what Reclus calls the ‘human’s role in the consciousness of nature’. Especially in terms of intrinsic cooperative properties of our societies, supporting the birth of new fields such as those we commonly refer to as environmental urbanism and urban ecology.

The following chapters will go deeper in understanding the relevance of historical thread of anarchist ideas in urbanism through comparison of two powerful authors that both maintained and built up the idea into their contemporary complexities of urbanization.

1.3 Two visions of ecological urbanism

1.3.1. Summary of the key lines of comparison

Although the purpose of this thesis is not giving a blueprint for a particular type of the city, urban system or urban planning approach it is noteworthy to clarify two major lines in which the above-described thread contribute to the field of ecological urbanism. It will be done in the following paragraph by presenting how they appear in the work of Peter Kropotkin and Colin Ward. By this, I attempt to clarify what is the aim of the thesis, especially in choosing these two figures to frame the relation of anarchist ideas with ecological urbanism.

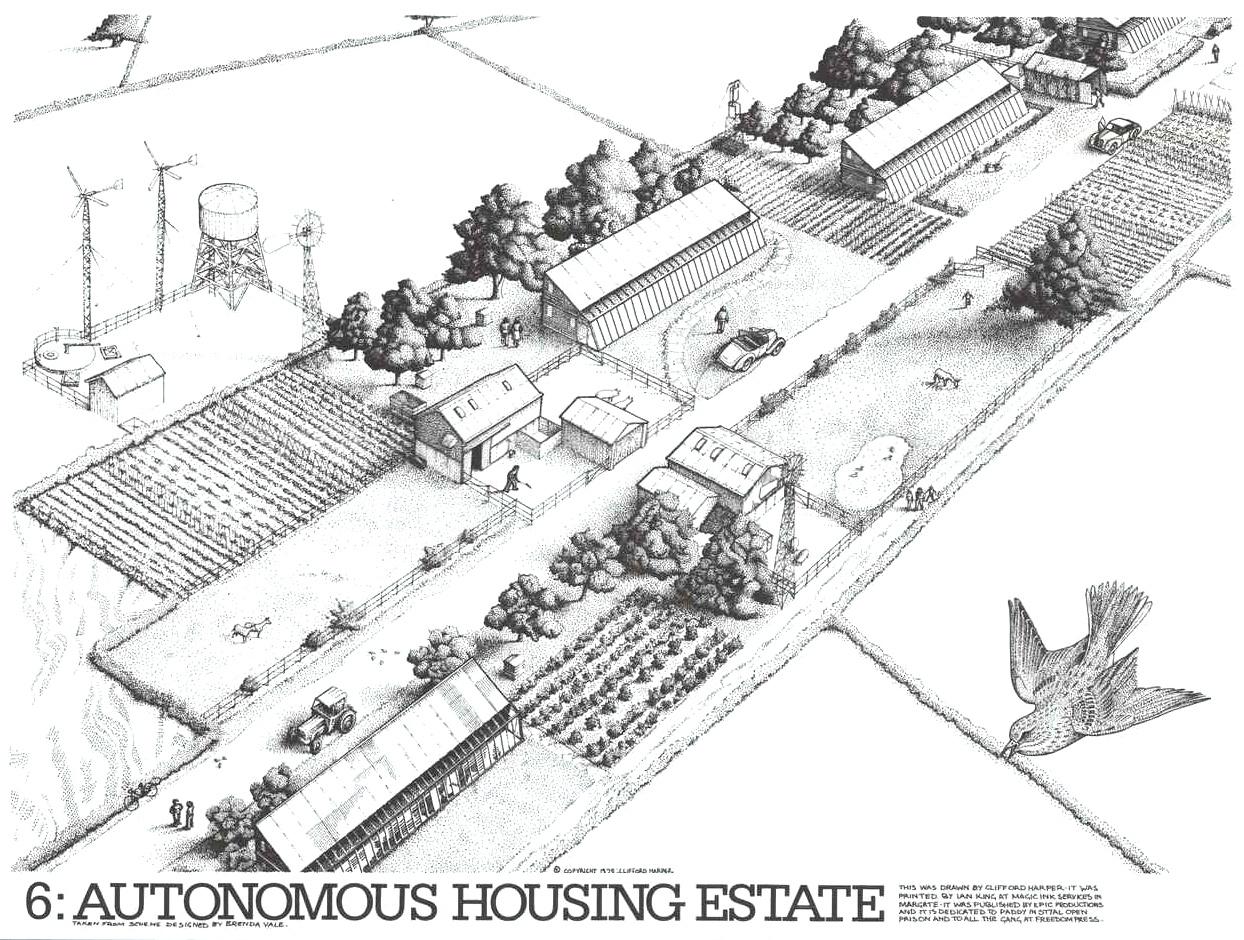

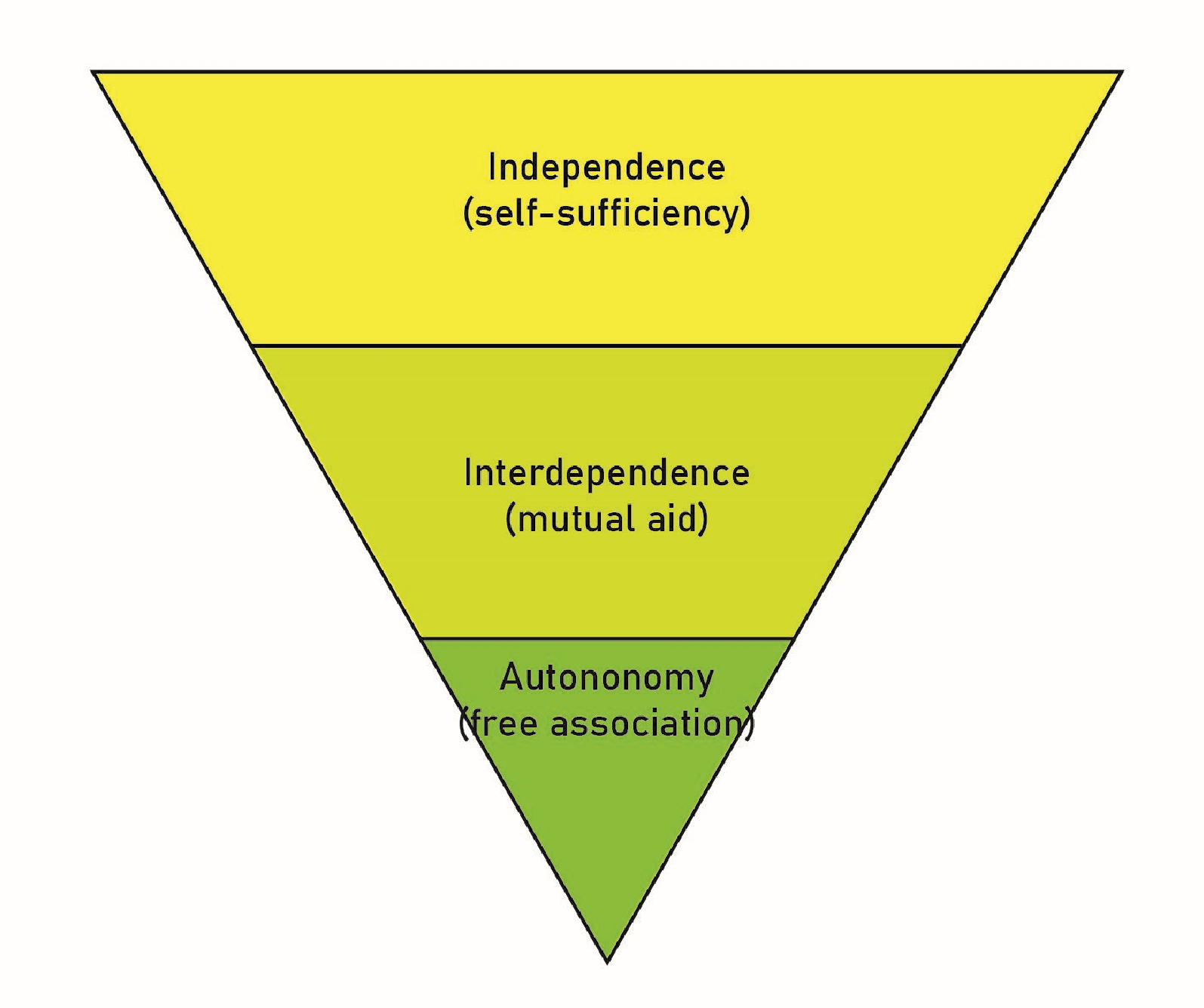

Two major lines along which the influence of anarchism on urbanism developed are a) the urbanism from below and b) nature-city fusion or more precisely proposal of city-countryside integration. Both of these lines present something that through a broad and diverse range of works on ecological urbanism is considered the normative categories of the field. Many books, designs, articles and conferences are trying to demarcate what could be a path to transform urban areas into environments systemically integrated into nature’s cycles and biosphere preservation methods. It goes hand in hand with citizen/dweller being an active subject of the change from participating in planning processes to taking bold actions in creating or building new environments. Both of chosen authors recognized that both of these lines are substantial for developing more than a better city — a better society. A closer look into works of both authors offers a good groundwork to read both of the lines as practical tools for implementing planning and design solutions.

1) Urbanism from below

Kropotkin’s work is since times of his visits to Swiss watch-makers communes inspired by Guillaume’s municipal communalism, presented in Ideas in Social Organization (1876). Guillaume sees municipal communalism as a tool to distribute power among skilful workers and peasants. The idea of political unit embedded in the territory on as local scale as possible imagines a citizen as a free agent that using own initiative, free association and mutual aid to achieve relative self-sufficiency is at the core of all Kropotkin’s work. In Fields, Factories and Workshops the city, the countryside, the region are all networked by relations of production and consumption of goods. At the same time, the governance is decentralized to large numbers of local autonomous bodies that are familiar with local conditions, needs and skills. In his vision of (post-)revolutionary life, The Conquest of Bread (1892), there is a ‘Spirit of Organization’ that directs people to act without a centralized body of power or urban plan to follow. It handles the distribution of food, renovation of streets, expropriation of housing, restarting the industry and seasonal labour on fields and crops. However, the most underlining idea of a driving force of urbanism from below is given in the book Mutual Aid (1902). Mutual aid or mutual support is for Kropotkin an evolutional factor present in all political and social processes, and therefore it is always present in the way how people organized, planned and acted in space. We just need to observe the niches in which people already build by their hand and means large fabrics of urban life.

Many experiences in alternative planning, such as Garden city, American regionalism or Spanish republican councils for planning are based on self-organized and self-managed actions by dwellers themselves. This idea is brought further after the second world war when urbanism from below becomes more present in discussions of architects and urban planners. This concept one of the key topics in Colin Ward’s work. Self-organization or as he calls it, dweller’s control is the main difference between mainstream housing distribution and the one in the anarchist approach. Freedom of person to choose, intervene and change its own housing conditions is something that can be traced in all his other observations and proposals. In Talking to architect (1996) two out of six alternative architecture approaches are directly connected to the inhabitant being in charge to change or build houses, and the third one is not about dweller’s control but maker’s or builder’s control of the process and use of the building. Finally, in commenting on, to him contemporary, practices of Advocacy Planning in USA and Public Participation in Planning in the UK he criticized the centralized governance and bureaucratic alienation. In Welcome, Thinner City (1989) he uses examples of Concerned Citizen Councils and Community Land Trusts in North American cities to the point that proper lessons about protecting the urban cores from decay or gentrification do not come from the partnership of government and businesses but residents involved in the community through organizations and citizen initiatives. These ideas culminate with Non-Plan, a proposal from 1967 made by Reyner Benham, urbanist Peter Hall, artist and architect Cedric Price and editor Paul Baker and in which Colin Ward took part by promoting and debating publicly. Non-plan was an experimental challenge to dominant practices of planning discipline to retreat from the determination as a key principle in conceptualizing the space and instead of breeding diversity of possibilities put in action by the dwellers themselves.

2) Nature city fusion

“Obviously, however, for me as an anarchist, the most important assumption was that our goal was not to be the instrument in the teaching programs of the principles of urban and rural planning, or the legislative basis for the implementation of it, as much as to favour the control of the environment, with an eye for examples where the ability to intervene on one’s own environment is accessible to all and not only to a particular minority. What can environmental education aim for, if not to enable people to control their own environment?” (Ward, 1992)

Kropotkin’s proposal for city-country integration is not a blackboard theory. His investigation in the history of European and non-European history of tribal, clan and village communities, all the

way to medieval cities and neighbourhood communities together with his fine-tuned critique of what is wrong integrated with its surrounding until the invention of mass production and big factories. Industrial revolution depopulated villages and degraded agriculture, deprived man and women from skills and detached humans from nature. Although we could say Reclus give much more philosophical account of this alienation, Kropotkin’s image of the ecological crisis is clear as well as his proposal to counter it. His idea of the urban ecological region consists of cities in which industry side by side with small scale agriculture, petty trade and craftsman workshops. It is connected by trains and public transport to suburban or subrural areas in which the scale of agriculture is adopted to the seasonal rhythm of crops, and even industry responds to this rhythm. In Fields, Factories and Workshops Kropotkin’s not only imagined an integration as a spatial process, but as well in labour dynamics, workers move from factories and work in fields during the season of sowing and harvesting. The small town plays a vital role as subcentres of local trade and production providing in one direction cities with a variety of foods and the other rural areas with finely crafted products. His analysis and proposal are more oriented on the relation of production and consumption than, i.e. Reclus and therefore presents an important bridge between the two lines: integration of functions and direct action in urban planning.

Colin Ward is here taking a different course. Instead of the grand-scale proposal, he focuses on everyday practices in the English countryside. For him, the connection of urban man and women to nature survived the industrial shock through allotments, holiday houses, small settlements and lifestyles of travellers and land squatters. He advocates more recognition for the importance of these practices and instead of regulating them, giving them space to develop organically.

Next to these, Ward argued that instead of the ‘cult of wild nature’ we ought to develop “environmentalism that values working landscapes and the built environment. As a writer, journalist and social critic he counselled against being enthralled to experts and maintained that we can learn much from the day-to-day creativity of ordinary people.”’ (Wilbert and White, 2011). On the one hand, Ward saw that social change that seeks for the central role of the community has to be environmentalist and have a regional foundation in combining best characteristics of rural and urban. On the other, he refrained from advocating intentional communities or blueprints like those of Ebenezer Howard exactly for the lack of inclusiveness on all levels. Instead, he proposed a combination of tactics on two different geographical arenas (Ward, 1992).

The first is a strong concept of Do-It-Yourself New Towns as autonomously built urban environments with a similar spirit to Garden City but with much more cooperative and direct action-driven inhabitants. However, he didn’t give a lot of inputs on the exact appearance of the concept he discussed in detail how and for what reasons it should be considered. These are investigated more in detail New Town, Home Town: The lessons of experience (1993). The other strategic ground are existing urban cores, or ‘inner city’ for which he claims is burdened as a synonym for poor areas. The only way to change Inner city is to put the power over land in the hands of communities. This is how allotment gardens are established in many areas; this is how parks are often defended; this is how affordability and

‘Unofficial settlements are seen as a threat to wildlife, which is sacrosanct. The planning system is the vehicle that supports four-wheel-drive Range Rovers, but not the local economy, and certainly not those travellers and settlers seeking their own modest place in the sun. These people have bypassed the sacred rights of tenure, but still find their modest aspirations frustrated by the operations of planning legislation. Nobody actually planned such a situation. No professional planner would claim that his or her task was to grind unofficial housing out of existence, and nor would any of the local enforcers of the Building Regulations. But all these unhappy confrontations are the direct result of public policy. Something has to be done to change it, and the hidden history of twentiethcentury housing offers some currently unconventional models.” (Ward, 2004).

“For me, and for people who want to make room for freedom of experiment in architecture and planning, the importance of flying the Non-Plan kite was the attempt to make room for do-it-yourself alternatives to the rival orthodoxies of the bureaucracy and of the speculative development industry. The attempt was not successful, but the fact that we discuss it 30 years later indicates what a rare challenge it was.” (Ward, 2000)

connection in residential areas are preserved etc. In Welcome, Thinner City (1989) he uses the example of Coin Street in London and the struggle in which resident fought of large scale development plans by London County Council and different corporations to stay in their homes under even better conditions. Through Community Land Trust and Housing Co-operatives, they proposed a scheme and one of the cooperatives realized small housing block: “[...]in the form of the hollow square, with small private gardens leading into communal space — the pattern develop in the nineteenth century in Holland Park. It [had] all this qualities we now seek in housing: quiet unassertivness, urbanity and domesticity” (Ward, 1989). In this aspect Colin Ward was still close to Kropotkin: promoting self-sufficiency in suburban and urban life in low-density urban typologies. He imagined possibilities for growing food and craftsmanship in combination with local trade along the suburban transport corridors in the same manner like Kropotkin.

In this sense, Kropotkin who wrote his last articles in 1920 and Colin Ward who wrote until 2010, present a comparable insight into a more than a century of development of decentralist ideas in the framework of urban planning. The two lines of comparison prove that their work has enough coinciding elements next to direct referencing to claim continuity of the idea. Also, the strength of their argument, proved by the fact that the prominent authors and mainstream planners (like Geddes, Mumford and Hall) referenced their work, proves that we can talk about distinct stream of influence on a wide field of ecological urbanism.

Based on these two lines of comparison, the thesis aims to function as a) reader — a guide through key concepts in which anarchist contribution was made to an ecological stream of urban planning. Here the guide refers as well to the key references in both authors bibliography and biography. As a reader, you should be able to navigate and discover connections between authors and the fields with which they were engaged and b) analytical tool — solid ground of different history-experiences. The thesis should support analysis and observation of historical and current examples of practice in from below urbanism and regional integration. From squats and anarchist collectives over cooperative housing bodies, neighbourhood initiatives and struggles and governmental policies, there is a large amount of lived experiences of what is conceptually evaluated in this text. We should be able to recognize those and understand their features as ecological, decentralist, both or neither.

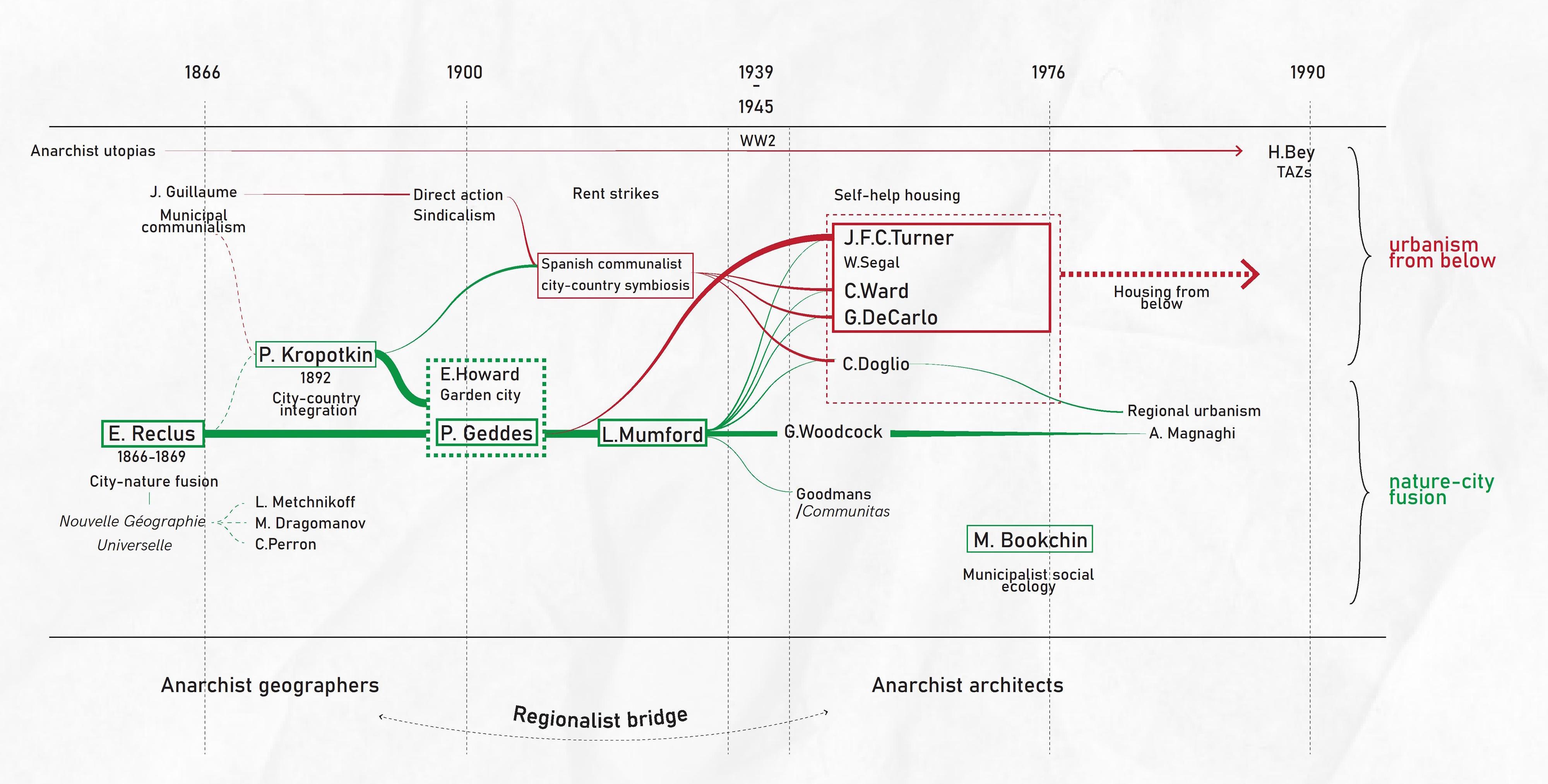

1.3.2 On the continuation of the idea — comparison of key concepts

After presenting along which lines are Kropotkin and Colin Ward discussable as ecological urbanists, this paragraph will compare them. Without intention to list all of the similarities and differences that these two productive and interdisciplinary authors have, I will put forward those I believe are most relevant for the aim described above. The comparisson is presented in a form of table for the calrity and overiew, and also to be a guide for reading the rest of the thesis.

“Establishing the basis of a contemporary radical theory of social ecology, [...] geographers believed that imbalances in nature reflected imbalances in human relationships and suggested that people base their use of the natural world on a respect for, and understanding of, its key properties. Kropotkin and Reclus assumed that sustainable human/environment relations could only be initiated through social transformation and fundamental changes in human values that would promote the demise of capitalism, racism, the modern State, gender inequities, and other forms of social hierarchy. They perceived that these changes would then be supported by a progressive sense of place, greater human interaction, and the centrality of love. While Kropotkin tried to develop a basis for higher moral standards from the natural world, Reclus assumed that moral development would come from the growing scope of our knowledge and attachment to key life systems.” (Breitbait 2009)

Comparison of Kropotkin and Ward: Key Concepts

| Peter Kropotkin | Colin Ward | |

| General perspective |

Relation Individual/Society(species) Kropotkin mainly focuses on the relation between individual and society or in the case of non-humans, species. The scale of his proposals is systemic, and his arguments are more often deductive than inductive. He debates freedom and self-sufficiency in terms of (in)dependence of the unit within the larger system. He is more interested in how society produces spatial relations than how the individual perceives it. In an example, he contrasts the individual’s right on the property to inherited benefits of the collective genius of anonymous mass that created the conditions for that property. |

Relation Human/Environment Ward’s work analyses relation of place, environment and people. Opposite from Kropotkin’s, his argument is more inductive, using examples of everyday practices he tries to prove the possibility of an alternative. Not that it is not systemic but much more nuanced and tangible in his observations he refrains from grand-scale narratives much more than Kropotkin. For him, as an anarchist, the freedom to act, to change the immediate environment, is a product of individual initiative, collective organization and political will. In that sense, he sees the environment as a dynamic result of many human-made vectors. |

| Territorial concept |

Agro-industrial region City and countryside should be fused into an interrelated region where agriculture and industry should be integrated and mutually provide manufactured goods and food. The citizen/peasant of such a region is a both manual and intellectually active person that takes part through cooperation and direct action in the political life of his town/village/communal federation. |

The Do-It-Yourself New Town The DIY New Towns are autonomously built urban environments with a similar spirit to Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of Tomorrow but with much more cooperative and direct action-driven inhabitants. In these settlements, the urban planning and local authorities are minimized only to site provision and essential services. New Towns are a hybrid of cooperative urbanism from below and the ecological idea of self-sufficient suburbia. |

| Urbanism from below |

Mutual aid Mutual aid and support are omnipresent social dynamic that is present in all times and places, and that directs in a self-organized manner both humans and non-humans towards the better environment. The citizens and peasants are since forever inclined to protect the loose institution of self-governance and self-sufficiency. The role of revolution is to strengthen these institutions and provide socially just distribution of food and goods throughout the agro-industrial region. |

Dweller’s control The best environment is created by its immediate users. Dwellers control is a concept that propagates presence, action and evaluation by final user of each step in the process of building and use of space. Ward presents a wide range of examples from squatter communities, Walter Segals system of self-help housing, cooperative housing enterprises, traditions in building cultures around Europe etc. Instead of revolution, Ward first recognizes that this is already happening and seeks strategies to protect and upscale these strategies through the support of architecture, planning and education. |

| Peter Kropotkin | Colin Ward | |

| The oikonomia |

Production vs Consumption The economic perspective of Kropotkin is focused on problems of production and consumption of food, goods and services both politically and in space. The distribution of wealth is more than just distribution of justice, and the economy is more than the efficiency of the market. In organized distribution, Kropotkin sees the key to collective management of resources, preserved and reproduced through generations of anonymous collective genius and mutual, endangered by the State and resulting in environmental degradation and alienation of people from nature. The cyclical and systemic approach to resource management is where Kropotkin’s environmental message comes out strongly. |

Maintenance and governing Ward, as an architect, to some extend withholds his observations to the built environment that is limited but regenerative. Two main processes he analyses are governance that produces new and maintenance that upkeeps exiting built spaces. His approach to the management of resources is more focused on the critique of the administrative and neo-liberal apparatus that mismanages and overuses the resources. He asks, can we have socially efficient and consequently energy-efficient cities? |

| The housing |

Redistribution Housing is in the language of Kropotkin recognized as basic need — a material necessity that needs to be provided to each worker, peasant and family. In his writings, we can find much more about the distribution of housing than about housing’s modes of production. As a material property housing is collectively distributed while privately consumed. In the book The Conquest of Bread chapter on Dwelling, he mostly discusses technical problems related to expropriation and distribution in post-revolution society. He discusses Housing in the realm of rights of property over the right of use. In that sense, we could almost say Kropotkin was one of the first defenders of squatting! Kropotkin proposes, maybe oversimplified, redistribution that he compares to traditions in managing agricultural land:‘Have we not the example of village communes redistributing the fields and disturbing the owners of allotments so little that one could only praise the intelligence and good sense of the methods they employ.1 |

Modes of production Ward gives much more attention to Housing than Kropotkin. He is probably the first author that tried to provide a comprehensive definition of Anarchist approach to Housing in the book of the same name. For him, the critical aspect of anarchist perspective on Housing is Dweller’s control. Housing is a central question in the production of a healthy environment. In that sense, Ward follows John F Turner — understanding Housing as a social and political dynamic that goes beyond a basic need. In looking for alternative approaches, he examined building co-operatives, tenants co-operatives, housing strikes and the illegal occupations and finally went on to consider anarchist attitude to town planning: The plan must necessarily emanate from an authority; therefore it can only be detrimental, The changes in social life can not follow the plan — the plan will be a consequence of a new way of life.’ |

| Peter Kropotkin | Colin Ward | |

| Green city |

‘Kropotkin extolled the virtues of the “intensive” or market garden approach to vegetable and fruit production. Kropotkin was particularly impressed by the techniques of the urban market gardeners of Paris, Troyes and Rouen, and the peasant farmers of Jersey, Gurnsey and the Scilly Isles. These intensive horticulturalists had developed systems of vegetable and fruit cultivation which were, for their time, some of the most highly efficient and horticulturally sophisticated forms of production available. The Paris gardeners, for example, on small plots within the limits of the city (they were attracted to Paris due to the prodigious quantities of stable manure), managed to export their produce to England. A carefully balanced organic feed was given to the crops on raised beds in frames or greenhouses and nurtured and forced by under soil heating (through steam pipes) and artificial light. Intensive agro-industrial market gardening methods when combined with ever-more advanced labour-saving technology, would in time allow even large urban agglomerations to be able to grow most of their daily fruit and vegetable requirements within the boundary of their own city, village or region. Vegetable and fruit production was to be integrated into urban life creating a more balanced urbarian (urb-agrarian) environment. Social and environmental stability was, he believed, dependent upon an environmentally holistic approach. An approach, moreover, that not only stressed the need to integrate industrial and agricultural production and consumption within the human environment but also with nature’s biological and evolutionary tendencies. [...] Kropotkin was one of the first thinkers to realise that a scientifically informed approach to organic composting techniques combined with new horticultural concepts, such as glass house culture, might allow the city to feed itself through the intelligent recycling of its human, animal and vegetable wastes.’ (Purchase, 2003) |

Before the explosion in the population in the nineteenth century, cities were green. [...] the provision of greenery in the urban environment is not primarily a matter of residential layout, for it depends on easy and daily access. In the nineteenth century, battles were fought to preserve ancient commons for public use, benefactors dedicated parkland to their communities and the city fathers established the tradition of public parks. In the twentieth century, planning standards were laid down to ensure that there was a certain quantity of open space per 1,000 of population.[...] The shift in perception that contradicted [...] hierarchical, statistical approach to the provision of green space in the city was a result of the emergence of what is loosely called the ‘environmental’ movement. This has taken a variety of forms, sometimes with very different aims. [...] The urban back garden has always been one of the most cherished of amenities, being used not only as an outdoor room, a storage space, a workshop, a dump, a playpen and safe playground, but also as the one place where people can indulge in their passion for growing things. The uses change from family to family and from time to time in the same household. The important thing is that the space is there and that the space Is theirs. [...] One branch is the intense growth of interest in wildlife, where changes in rural life, especially in agriculture, have resulted in the paradox that, like the gypsies, wild creatures can often best be studied in the cities. [...] over 300 urban wildlife sites is not only an indication of a change in perception, but also of altered professional and official attitudes in response to the incredible spread of local wildlife groups since the 1970s. [...] The rediscovery of urban farming began with the initiative of Inter Action in Kentish Town in London in 1972. It has a community workshop, riding school, stable, sheep, goats, pigs, rabbits, geese, chickens, ducks and a cow. [,..]The greening of the cities, in thousands of little local projects, is a genuinely popular movement made possible by the thinning-out of the overcrowded industrial city.L...] They have symbolic and historical significance as the only enshrinement in law of the ancient and universal belief that every family has a right of access to land for food production. (Ward, 1989) |

| Similarities |

• both wrote persistently in periodicals of their time. They were editors, journalists and debaters • although aiming for different audiences, they promoted anarchism as inherent to ‘spatial’ disciplines • mutual aid is not a political concept but the outcome of the sociable nature of humans and animals • cooperation, direct action and free association were underlining principles beyond anarchist ‘ideal’-they are omnipresent factors of social organization and progress • all of these principles exist parallelly to the will and power of the State and are part of everyday life dynamics • also, both believed that political and social organization had a fundamental impact on the environment and living conditions • means of creating that environment and condition ought to be in the user’s hand • both idealized autonomous, self-sufficient city like the city-state of Middle Ages |

| Differences |

• Kropotkin worked on proving anarchism is scientific, Ward worked in making it respectable • Kropotkin’s targeted audience was scientists and workers, Ward’s professionals and tenants • Kropotkin was interested in systematic overview often retreating in grand narratives; Ward avoided using grand narratives and large scales • A good example is a revolution. For Kropotkin the only path to successful social transformation, for Ward a goal too far — a deception. • For Kropotkin, housing is a basic need to be distributed, for Ward centre of individual’s freedom a users’ external environment. |

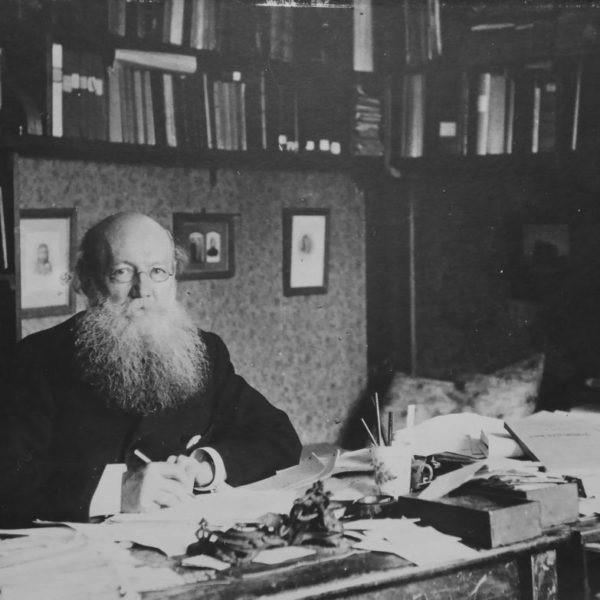

2 Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921)

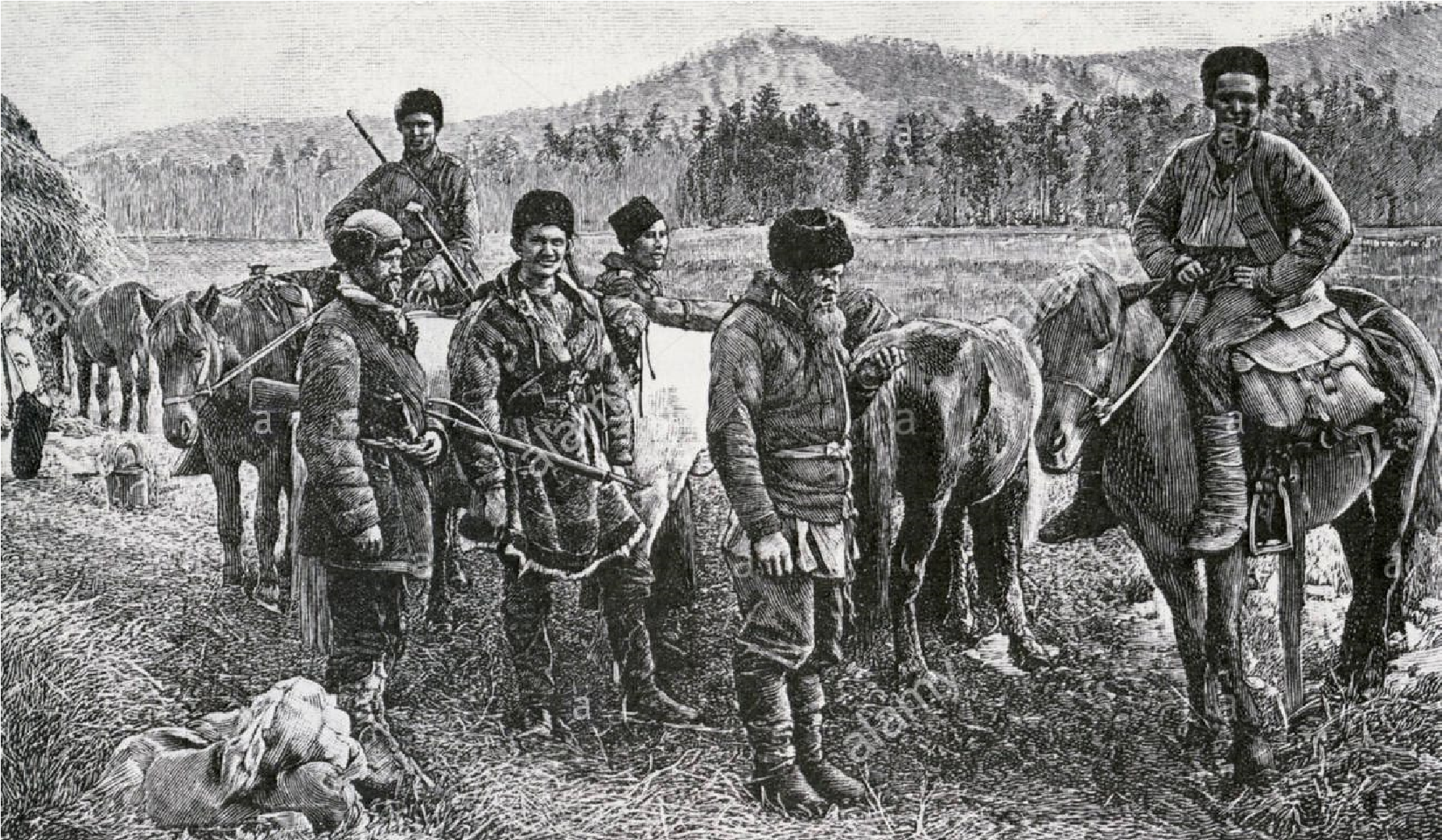

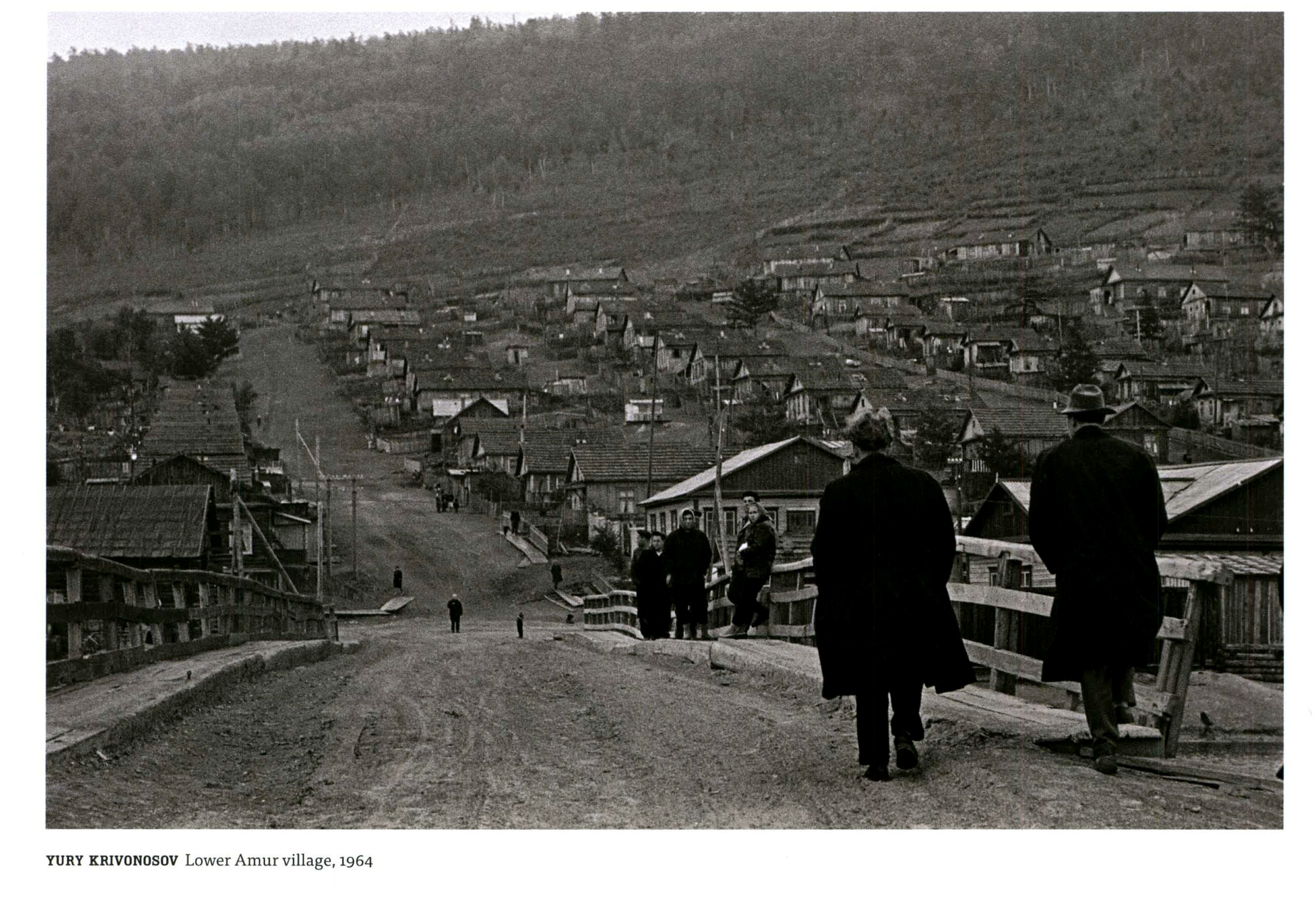

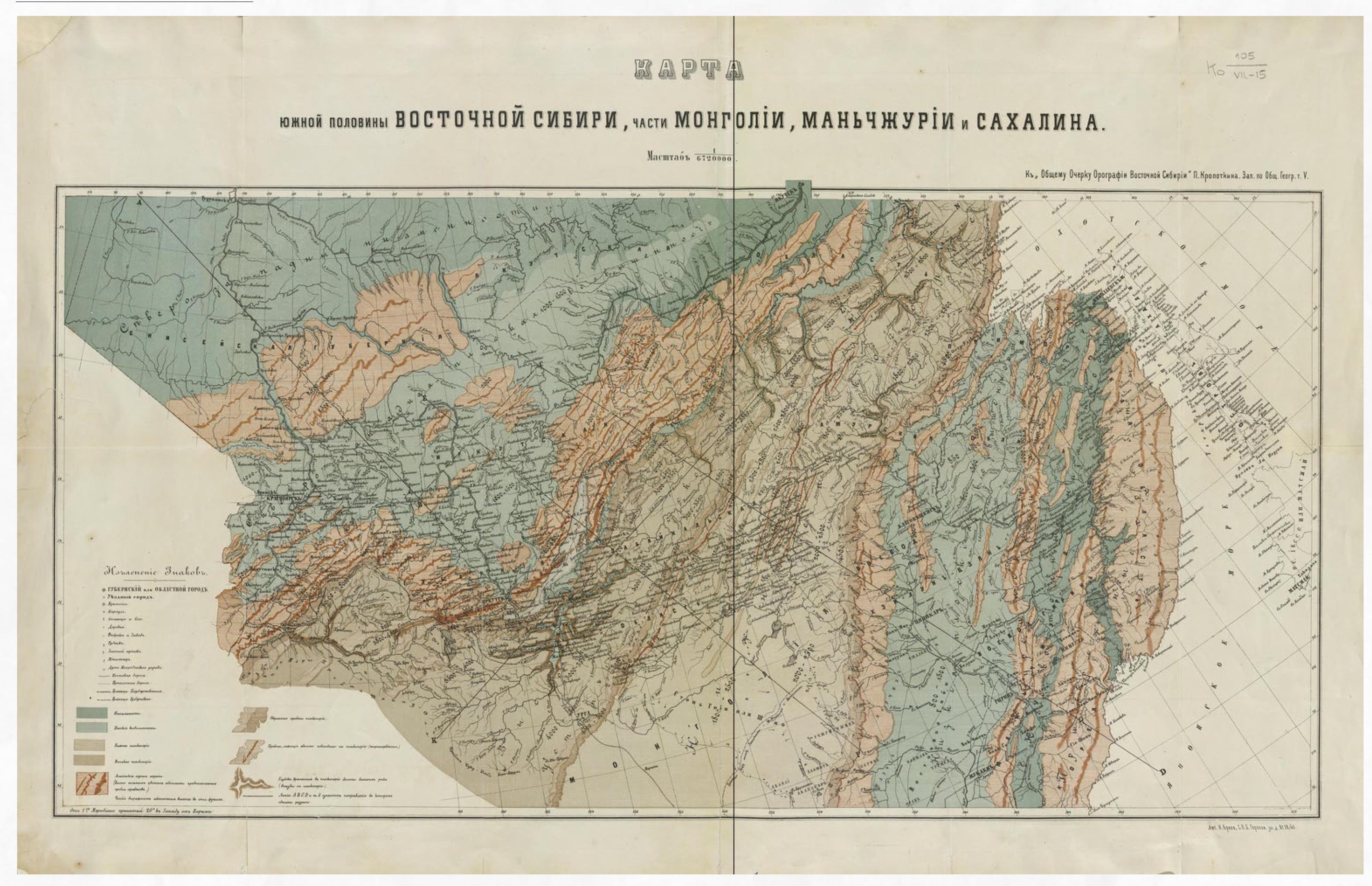

Source: https://libcom.org/gallery/anarchist-portraits-clifford-harper

Peter or Pjotr Kropotkin is Russian geographer, scientist and anarchist that could be given a credit of one of the most prominent figures of the political philosophy bridging the 19th and 20th century. He is born in 1842 in Moscow into an aristocratic family of landlords and is given the title of a prince as direct heir of the pre-Romanov royal dynasty of Rurik’s. Peter receives the education in military school and serves as an officer in Siberia having various ranks and position during the military career. Simultaneously, he receives an education in geography. As geographer, explorer and biologist Kropotkin was a first-class natural scientist. In 1862, he exiles himself to eastern Siberia to escape the life of noble on Tzar’s court. Precisely, at the age 21, he is offered by the Tzar Alexander II to choose a regiment, and Kropotkin decides to go to Transbaikalia, a remote and savage Siberian province in which Russian imperium is still weak. Apart from his rebel towards his noble roots and military discipline, his choice was partially influenced by his dislike for cities and crowds at his young age (Purchase, 2003). Once he arrives in Siberia, he uses his education as geographer to organize both scientific and military expeditions into Siberian mountains and plains. These travels are later compared to Darwin’s expeditions to Galapagos with MHS Beagle. In this period Kropotkin researches the flora and fauna, topography, climate, geology, and anthropology of remote areas of Manchuria, Lena mountain and Amur region. With these travels, he proves that the orography of north-east Asia is significantly different from what was believed before. He describes plateaus as a distinct type of relief as relevant as a mountain range. Observations on prehistoric glacial movements convince him that during the Ice Age the ice went as south as to 50th parallel turning the steppe into a mosaic of lakes and forests, that gradually turned into grasslands and even desert. It is one of the first scientific attempts to use climate changes as an inevitable factor of history of human civilization (Davis, 2016). It will take half a century for this to be considered seriously on a larger scale in other natural sciences.

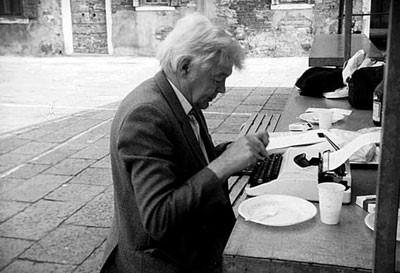

After the voluntarily quitting his military career and ties to royal origins he dedicates himself to science, philosophy and politics very soon being imprisoned for his believes in 1847 in the legendary prison of Peter-Paul fortress. As a noble, he still enjoys the freedom to write and do scientific research during his imprisonment. From this point, his scientific work intensely intertwines with his work as revolutionary. During following turbulent decades of life, he travels to Switzerland and Belgium, engages with many prominent socialists and anarchist of his time like Jura Federation and Workers International, rejects the offer to be the director of Russian Society of Geographers, does numerous geographical expeditions, is exiled and imprisoned numerous times. His extraordinary path inspired several authors to make his biographies from different angles (Woodcock, 1971; Miller, 1976; Woodcock and Avakumovic, 1978; Shatz, 1995; Marshall 2009; Ferretti 2011; Harman 2018, Johnson, 2019). After several exiles in Switzerland, France (where he spent four years in prison) he settles in the United Kingdom in 1886. His years in London are for him the most productive period as a writer still insisting on both of his passions: geography and anarchism. Although already earlier in Switzerland he took part in the founding political journal Le Revolte, in London he starts to write regularly for the British periodicals, in particular the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1768), Statesman’s Year Book (1864), The

Nineteenth Century (London, 1877) and Nature (London, 1869). As Ferretti (2017) acknowledges, these articles pay Kropotkin living and are a steady income for an unstable revolutionary lifestyle. On top of that, they are a polygon for developing his most famous books, such as Fields, Factories and Workshops (1898), Mutual Aid (1902), Modern Science and Anarchism (1903), The Great French Revolution (1909) and Ethics (1921), all of which are practically a collection of articles published in the Nineteenth Century or other periodicals (Ferretti, 2017).

As political philosopher Peter Kropotkin developed a relatively straight forward set of proposals about how to tackle centralised power, labour division and negative consequences of the industrial revolution. He advocated decentralised society in which most possessions are communally owned and where individuals are integrating manual and intellectual labour voluntarily associating into selfgoverned communities and workers cooperatives. On the geographical scale, this implies a city as entity interconnected with its surroundings into an ecological region. This region has urban structures, agriculture, nature, and industry integrated and downscaled to the proximity of every working man and women. Kropotkin elaborates his stances on the economy, often referring to both production and consumption in which the primer argument to blur the boundary is his standpoint on economies’ role in natural resources management. As Graham Purchase (2003) argued he was “the first person to mould proto/ecological concepts within the economy, geography and biology coherently into a social and political economy.” The key contribution he gave to the debate on humankind-nature continuity is his latest work on mutual aid. Proving the scientific dimension of anarchist thought in parallel with criticising social Darwinism as a foundation to capitalist competition became an important objective in the later years of his life. He is a pioneer of urban environmentalism as a scientific field, giving elaborated arguments about how our social behaviour in urban surroundings causes measurable and comparable biological effects.

Kropotkin, as an author is both structured thinker and passionate idealist. These two characteristics are mutually complementing in his writing, contributing to the powerlessness of his argument. His idealist and principled perspective of nature-society relations are founded in the book ,Mutual Aid’ from 1902. He, in a holistic (again structured) manner, uses his observations as geographer to complement the Darwinist concept of nature’s competition with cooperation (Woodcock and Abakumovic, 1978) Kropotkin sees cooperation or mutual support as equal, if not a more significant force in both, biological and social, coexistence. Cooperation plays a significant part in all of his work, including The Conquest of Bread and Field, Factories and Workshops. Here he calls the driving force of cooperation ‘the Spirit of organization’ that leads post-revolutionary agrarian and industrial workers. This idealistic belief is ground for his grand-scale proposals.

On the other hand, Kropotkin is also a pragmatic writer with belief in scientifically informed approach. Since his early works, he uses a similar structure of argument: observing a real-life example, detecting a cause of the problem or a failure, then more or less systematically relating it to higher ideal grounds and principles, and occasionally proposing better ways instead. Finally, Kropotkin’s political philosophy has some limitations, some of which could be explained as consequences of the time in which he lived. In his theory, he relies on revolution as the only possible way to transform society assigning it almost divine character. Similarly like for mutual aid, for the revolution, the driver is ‘spirit of organization’, a rather thin concept that he hardly explains. These are the significant critiques that many who disagreed with his ideas used against his proposals. The third note to limits of his thought is ecological and is as well documented by Graham Purchase in his elaborate doctoral thesis Peter Kropotkin Ecologist, Philosopher and Revolutionary (2003). Compared to his contemporary fellow anarchist geographer Elisee Reclus Kropotkin has a more human-centred approach to science and politics. Unlike Reclus, he never became vegetarian or advocated recognition of non-human voices.

Source: https://www.alamy.com/

Source: https://theartbookreview.org/2014/04/27/siberia-in-the-eyes-of-russian-photographers/

Source: https://runner500.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/img_0890.png

Peter Kropotkin, after the exile to London, spend his lifeless adventurously, writing and communicating with the rich network of his contemporaries and occasionally taking part in protests around England. “He used this time to combine the scattered insights of Fourier, Proudhon and Bakunin with the living ideas of Russian populism and European anarchism into a comprehensive social philosophy. His background as a professional natural and social scientist allowed him legitimately to extend these concepts into anthropology, biology and economics. In doing so, he became one of the founders of modern environmental science and political ecology. A speaker of over 20 languages and able to write with a distinctive style in many European ones, combined with the fact that he was forced to earn a living from his pen, meant that his output was vast, his style remained popular, and his influence was worldwide.” (Purchase, 2003) It remained so until 1917 when he returns to Russia. He hopes to see the worker’s revolution turn into a true decentralized integration of countryside and city through the cooperative spirit of Russian peasants. Instead, he is devastated after finding out the Revolution turned into an oppressive dictatorship of Bolshevism. Deeply disappointed he retreats Dmitrov and dies in 1921, at the age of 79. His funeral is attended by 100 000 people including many globally known anarchists, socialists and scientists and was for coming 70 years last public protest in Soviet Russia.

Kropotkin is during his life supported by his wife Sofia Grigoryevna, also a scientist with an international career. Let it be noted that Kropotkin gives little attention to the struggles of the early feminist movement and does not often elaborate on the position of women in his theory. However, when Peter’s health deteriorates, Sofia gives up her career and dedicates herself to supporting him. This might be fundamental to his productivity and long life since in the second half of his years his health is seriously damaged by his travels to Siberia, years in prison and restless fight for the ideal of anarchist society (Purchase 2003).

Mutual Aid

Peter Kropotkin’s central contribution, to both political philosophy and arguably natural sciences, is his description of mutual aid or support within and between the species as a key factor of evolution. His book Mutual Aid (1902) is one of the earliest serious attempts in social and political theory to undermine that social life can be explained in the competitive and aggressive terms of social

“Kropotkin was one of the first thinkers to realise that a scientifically informed approach to organic composting techniques combined with new horticultural concepts, such as glass house culture, might allow the city to feed itself through the intelligent recycling of its human, animal and vegetable wastes. Kropotkin believed that, in this respect, we had much to learn from the Chinese and Japanese; noting that, through their advanced composting, they were able to maintain dense populations through “utilising what we lose in sewage.” (Purchase, 2003)

Darwinism. At the time when the book is published, Darwin’s, Wallace’s and Huxley’s concept of brutal, competitive struggle in the natural world is employed to explain slavery, war and poverty in and among societies. On the opposite side, Kropotkin recognizes in both nature and society forces of cooperation as a key factor in survival, coexistence, ensuring resources, empathy and reproduction of a kind. Although mainly presented in his seminal book Mutual Aid-Factor of evolution, all works of Kropotkin rely on the argument that there is a strong inclination to collaborative, mutually supportive practices in all aspects of life. This is the most important principle on which he builds argumentation for the possibility of an anarchist society. The book Mutual Aid uses his geographical, biological and anthropological observations to show that mutual aid is not just care, or solidarity but arises from a ‘biological and environmental theory, pertaining to evolutionism, and is evolution’s force parallel to competition at least. Kropotkin shows that animals from most primitive ones like bees and insects to the most complex — like mammals, monkeys and humans are very sociable and tend to share, care and cooperate in the form of reciprocal altruism. In the rest of the book, he seeks for the same principle in human societies illustrating examples among what he calls ‘savages’ and ‘barbarians’, rural communities, medieval cities and all the way to contemporary society. These tendencies of people to self-organize in order to share resources, build communally, support the weak and unlucky are continuous and omnipresent in all phases and geographies of humankind.

If we are sociable and compassionate beings since most early ages, why do we need a State or any form of a centralized authority to organize us? (Purchase, 2003) This is especially observable in our times when due to the global environmental crisis, migrations and pandemics there is a large-scale response almost by the rule not organized by the State but by the community-driven by mutualism. Like an example of Argentinian Barrios de Pie, 2000 small-scale communal kitchens that distributed meals during COVID-19 pandemic to 500 000 seniors around the country.

Integration of city and countryside