Tony Dowmunt

Autobiographical documentary - the ‘seer and the seen’

Abstract

Despite the apparent inadequacies identified by Elizabeth Bruss and others, of film as a medium for autobiography, first-person film-making has had a long history, stretching back decades. Its current growth may have been stimulated by the increasing availability of accessible digital recording technologies, but filmmakers have been attracted to it for over half a century, and the issues it raises are central to the development of our ideas about documentary. This article argues that the particular circumstances of autobiographical film-making, the confrontations it engenders between the film-makers’ selves and the others that appear in their films, continually raise key questions about the (power) relationship between film-maker and subject in an always overt and often reflexive fashion. This is particularly the case when the film-maker self-shoots - is both the 'seer and seen', observer and observed: in self-shot autobiographical work these key questions are often clearly displayed precisely in the way that film-makers make use of their cameras.

Elizabeth Bruss wrote that: ‘There is no real cinematic equivalent for autobiography ...’ (Bruss 1980: 296). Her view was that in autobiography, the logically distinct roles of author, narrator and protagonist are conjoined, with the same individual occupying a position both in the context, the associated ‘scene of writing’, and within the text itself.

(1980: 300)

This lack of ‘conjoinment’ is particularly evident in documentary films in which the autobiographer appears in front of the camera, at that point probably delegating some of the functions of authorship (framing or camera position for instance) to the camera operator. Because film-making involves, Bruss says, ‘a disparate group of distinct roles and separate stages of production’, this undermines the ‘unquestionable integrity of the speaking subject’ (1980: 304) that she holds to be an essential component of autobiographical authorship.

There are two (very different) ways in which I am interested in challenging her assertion here. First, whilst her characterization of film-making as necessarily involving a wide range of distinct authorial agents is true for the more mainstream and industrial forms of film-making, it has never held for the more avant-garde practices, and has also been increasingly undermined, across all forms, by developments in video and digital technology (in particular camcorders, mobiles, webcams and desk-top editing), which allow for individual authorship in hitherto impossible ways.

Second, her requirement that the autobiographical speaking subject has an ‘unquestionable integrity’ (which is undermined by the range of authorial agents often involved in film-making), now seems an undesirable goal, given that we are so aware of the inevitably fragmented and relational nature of the self. Indeed, this awareness means that film is a particularly useful medium for contemporary forms of autobiography: ‘film may enable autobiographers to represent subjectivity not as singular and solipsistic but as multiple and as revealed in relationship’ (Egan 1994: 593). So the multiple perspectives (of cameraperson, editor and subject/protagonist for instance) that many film-making practices entail may make film/video appropriate media for the representation of contemporary non-unified selves. Certainly this is what Catherine Russell believes when she describes how the ‘three “voices” - speaker, seer and seen - are what generate the richness and diversity of autobiographical filmmaking’ (1999: 277).

Bruss thinks that autobiographical films have ‘a tendency [...] to fall into two opposing groups - those that stress the person filmed and those that stress the person filming - replicating the split between the “all perceived” and the “all perceiving”’ (1980: 309). However the tensions between these two opposites (or between the three ‘voices’ Russell identifies) are productive, at least for those of us interested in critical autobiographical film-making. Most autobiographical documentaries exist somewhere in the middle ground between these two groups, and so tend to subvert both the omniscient surveillance of the ‘other’ implicit in her phrase the ‘all perceived’, and the sovereign subjectivity conveyed by the phrase ‘all perceiving’. Bruss herself acknowledges the possibilities for self-fragmentation film offers when she complains that

The unity of subjectivity and subject matter - the implied identity of author, narrator and protagonist on which classical autobiography depends - seems to be shattered by film; the autobiographical self de-composes, schisms, into almost mutually exclusive elements of the person filmed (entirely visible, recorded and projected) and the person filming (entirely hidden, behind the camera eye).

(1980: 297)

Of course, the apparently exclusive categories of ‘person filmed’ and ‘person filming’ have been brought together (potentially, and, in the video diary form, actually) by recently available digital technologies. But the practice of autobiographical film goes back further than this recent history. As P. Adams Sitney’s writing makes clear (1978: 199-246), film-makers such as Jerome Hill, Stan Brakhage and Jonas Mekas were working autobiographically well before Bruss declared that autobiography had no cinematic equivalent. Indeed, the possibility of autobiographical expression in film, where ‘roles of author, narrator and protagonist are conjoined’ (Bruss 1980: 300), was inherent in Alexandre Astruc’s concept of ‘La Camera-Stylo’, elaborated in an essay written in 1948 (1968), which overtly stresses the similarities between cinematic and literary authorship. Joram Ten Brink shows how the reflexivity in Rouch’s Chronique d'un ete was a ‘direct consequence of the “Camera-Stylo”, and how for Rouch and Morin (the authors of the film) their “self”, either visible or obscured, is often a reference point, and inseparable from the “text” of the film’ (2007: 241).

The challenges of autobiographical film-making outlined by Bruss were also taken up on the other side of the Atlantic. Michael Renov’s writing has traced the development of the autobiographical voice in documentary over the last two decades. He cites the work of Mekas, Lynn Hershmann and Ilene Segalove in the 1980s as inaugurating a ‘new autobiography in film and video’ (2004: 104-19), part of:

the recent outpouring of work by independent film and video artists who evidence an attachment both to the documentary and to the complex representation of their own subjectivity.

(2004: 109, original emphasis)

Jim Lane’s book The Autobiographical Documentary in America (2002) concentrates more on work by film-makers (like Ross McElwee and Ed Pincus) who emerged from the Direct Cinema movement. The hand-held, observational style of Direct Cinema, with its long takes and suspicion of conventional editing, was in many ways suited to autobiography, as David MacDougall suggests in a comment on the embodied nature of observational camerawork: ‘In place of a camera that resembled an omniscient, floating eye [...] there was to be a camera clearly tied to the person of an individual filmmaker’ (MacDougall 1998: 86). A camera clearly tied to a person offers a kind of subjective ‘claim on the real’, which connects these film-makers to their roots in Direct Cinema. They shared a belief in actuality, in the ‘referential’ function of film, which distinguished them from the avant-garde. At the same time Lane points out how

By repositioning the filmmaker at the foreground of the film, the new autobiographical documentary disrupted the detached, objective ideal of direct cinema, which excluded the presence of the filmmaker and the cinematic apparatus.

(2002: 12)

On this side of the Atlantic this move from observational to autobiographical documentary has been mirrored most clearly in the career of Nick Broomfield, initially trained in observational documentary at the National Film School. Despite the ‘autobiographical’ presence Broomfield has cultivated in his more recent films, he is not an autobiographical documentary maker, but, as Stella Bruzzi convincingly demonstrates, someone who uses his ‘alter ego of the friendly man with a boom’ (2006: 109) as a particular film-making strategy: so ‘Nick Broomfield ^ “Nick Broomfield”’ (2006: 208). He made this distinction very clear himself when he made a series of television advertisements - starring ‘Nick Broomfield’ - in 1999 for Volkswagen. He appears - almost parodying his persona - as the familiar friendly, but slightly bumbling man with the boom and headphones, testing out the cars’ safety features.

So ‘Nick Broomfield’ is a partly fictionalized character that Broomfield mobilizes for narrative purposes in his films. This is perhaps made most clear when the device breaks down (and the films become more ‘authentically autobiographical’), as in the sequence in which an obviously impassioned ‘Broomfield’/Broomfield storms the ACLU stage to confront Courtney Love in Kurt and Courtney (Broomfield 1998), or in the final interview sequence with Aileen Wournos in Aileen: The Life and Death of a Serial Killer (Broomfield 2003), just before her execution. In her discussion of this sequence Bruzzi describes this film as among his ‘least showy’ and ‘most sincere’ works since he began involving himself as author on screen (2006: 217).

Broomfield’s work also developed out of the Direct Cinema tradition whose original ambition was to convey on film the truth of ‘being there’, of unmediated presence. What became clear to Broomfield and many others, was that the truth (and the drama) of ‘being there’ inevitably involved their own (the filmmaker’s) presence, and to deny it was both dishonest, and missed much of the actual drama of the documentary-making process. As Jon Dovey puts it:

More than any other film-maker Broomfield’s work represents the documentary tradition confronting and taking on the epistemological challenges of contemporary culture and incorporating them into a structure which relies crucially on the foregrounding of subjectivity in order to be able to make sense.

(2000: 33)

However, despite this foregrounded subjectivity, Broomfield and other filmmakers like Michael Moore who work in the same vein, remain quite hidden. We ‘know nothing of their private selves - only their narrative personae’ (Dovey 2000: 40).

There is however a growing body of documentary film work by male film-makers that pushes the first person mode much further towards the confessional. [...] Ross McElwee is widely regarded as one of the leading film-makers in this territory.

(Dovey 2000: 40-41)

McElwee, like Broomfield, started working within the Direct Cinema tradition, before becoming more directly autobiographical: ‘I began making autobiographical films because I felt that I just didn’t have whatever it took to maintain that artifice of being the invisible person from behind the camera’.[1] His first film in this mode - Sherman’s March (McElwee1986) - dramatizes the transition. It begins - ostensibly - as an historical film about General Sherman’s march to the sea in 1864, but is quickly side-tracked into an exploration of McElwee’s tortuous love life. McElwee has pursued this technique in his films in the twenty years since Sherman's March - always positioning himself autobiographically and personally within the social themes and issues that his films also explore. So Six O’Clock News (McElwee1996) is about his feelings as a first time parent concerned for his new baby, counterpointed with a nervous critique of sensationalist news coverage of murders and natural disasters (as he put it: ‘seeing the world through the lens of fatherhood for the first time’[2]), and the more recent Bright Leaves (McElwee 2003) tells the story of his family’s involvement in the tobacco trade interspersed with more personal reflections (a meditation on legacy and heritage [...] and what legacy means’[3]). He approaches the social world and conventional documentary themes by filming, and filtering them through, his personal, autobiographical experience, as he put it himself in an interview:

[.] melding the two - the objective data of the world with a very subjective, very interior consciousness, as expressed through voice-over and on-camera appearances.

(Lucia 1994: 32)

As we have seen, the work of McElwee and Broomfield, in their self-referential use of themselves on-screen (their refusal to be ‘the invisible person from behind the camera’), represents a radical shift from the conventions of Direct Cinema. Renov has pointed out how:

During the direct cinema period self-reference was shunned. But far from a sign of self-effacement, this was the symptomatic silence of the empowered who sought no forum for self-justification or display. And why should they need one? These white male professionals had assumed the mantle of filmic representation with the ease and selfassurance of a birthright.

(2004: 94)

McElwee’s and Broomfield’s breaking the ‘silence of the empowered’ can therefore be seen as an abandonment on their part of the authority of anonymity, as well as a declaration of ‘honesty’. However, the new ‘white male professionals’ who embrace self-reference - Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock as well as Broomfield and McElwee - have themselves been critiqued for the way they use a clearly signed lack of self-assurance in their films. All four of them in different ways mobilize what Dovey has characterized as the ‘Klutz persona’ - whose pratfalls on-screen mask their authorial mastery and skills - ‘a failure who makes mistakes and denies any mastery of the communicative process’ (2000: 27).

Paul Arthur (1993) has posited what he calls a ‘documentary “aesthetics of failure”’ to explore the ‘klutz’ phenomenon. He traces how - from the 1930s through the Direct Cinema period to now - documentary has sought to guarantee its authenticity by ‘repudiating the methods of earlier periods from the same perspective of realist epistemology’ which he defines as ‘the absolute desire to discover a truth untainted by institutional forms of rhetoric’.

Arthur goes on to assert that

Each new contender (in the search for untainted truth) will generate recognizable, perhaps even self-conscious, figures, through which to signify the spontaneous, the anti-conventional, the refusal of mediating process.

(1993: 109)

In the current period (since the 1990s) that figure is the klutz - the only kind of film-maker whose truth claims, by virtue of his[4] appearance on-screen, we will be inclined to believe in our sceptical, postmodern times. Nowadays, as Arthur goes on to say,

it is required that filmmakers peel away the off-screen cloak of anonymity and, emerging into the light, make light of their power and dominion [...] But a willingness to actually take apart and examine the conventions by which authority is inscribed - as opposed to making sport of them - is largely absent.

(1993: 128)

So the klutz is a confidence trick, the latest attempt to shore up documentary film-makers’ authority and realist truth claims. When Broomfield messes up his interview with Terre Blanche in The Leader, His Driver and The Driver’s Wife (Broomfield 1991) or Michael Moore fails to track down Roger in Roger and Me (Moore 1989), their displays of being out of control merely reassert their actual control over their material - giving an impression of its authenticity and therefore confirming its (and their) authority. ‘Out of control-ness’ becomes a rhetorical device that signifies authenticity, as well as modesty: ‘[...] it is exactly the open admission of [.] patriarchal mastery in disarray - which performs the labour of signifying authenticity and documentary truth’ (Arthur 1993: 132).

The master may be in disarray, but he is still master. Arthur’s unhappiness about these film-makers’ lack of a ‘willingness to actually take apart and examine the conventions by which authority is inscribed’ contains an implicit plea for film-makers to adopt techniques that are more genuinely self-reflexive, that problematize rather than tacitly reproduce documentary authenticity.

MacDougall’s concept of ‘deep’ reflexivity is useful here. He believes that ‘deep’ reflexivity requires us to read the position of the author in the very construction of the text’ (1998: 89). So for MacDougall as a film-maker it is his manifested relationships with his subjects that is key: ‘If I am self-reflexive, that self-reflexivity must be about the relationship between us[.]’(1998: 91). This relationship, properly revealed, enables film-makers to ‘take apart and examine the conventions by which authority is inscribed’ (Arthur 1993: 128). I think this examination is perhaps most obviously present in self-filmed autobiographical work - for instance in the work of Ross McElwee, in which his own presence as camera-person/director is a constant theme of his films.

In Time Indefinite (McElwee 1994) - which centres on his relationship with his family, particularly his complex feelings about his father, at a time when he himself is contemplating marriage - his camera runs out of battery power just as he’s announced his engagement to his girlfriend Marilyn, in a large group of relatives that have gathered for a family birthday. McElwee cuts to some camcorder footage shot by one of his relatives, and suggests in voice-over that his father was giving out a ‘force field that plays havoc with my equipment’. There is also the sequence from Six O’Clock News (1996) that comes around half an hour into the film. The basic theme - as I have already mentioned, McElwee’s increasing feelings of vulnerability as a new father in the face of the daily horrors and disasters he witnesses on the 6 o’clock news - has already been established. In this sequence he allows himself to become the subject of a local news programme, allowing them to film him as a curiosity: the strange man who films his own life. By intercutting his own footage of the crew’s visit to his flat with the item that ends up on the 6 o’clock news, McElwee reflexively portrays an amusing struggle between conflicting cinematic ethics, styles and objectives. He makes us aware of his own - and other - film-making practices within the piece by filming the three takes by the news crew as they are coming through the door, making their apparently ‘spontaneous’ introductions. Once they are installed in his kitchen, he competes (unsuccessfully) for the best camera position with the news cameraman, with McElwee ending up disadvantaged by having to shoot into the light from his kitchen window. His customary ironic voice-over (added at the editing stage) is present throughout the sequence, confessing his personal difficulty in coming up with ‘soundbites’ for the reporter, and musing, for instance, on the nature of ‘real’ (or Hollywood) films versus his own practice of making documentaries.

Of course these examples are highly reflexive (in the sense that the filmmaking techniques draw attention to their own construction) - especially, of course, when McElwee is being filmed himself by the News crew. I think that reflexivity forms an important element in most contemporary approaches to first-person film-making - particularly those that involve self-shooting. I am interested here in how these films focus on the material, reflexive relationship of the film-maker/autobiographer to the camera, the film-making process and to the other subjects of the films, to address more closely the issue of the oppo- sition/division between seer and seen explored above. This also, of course, returns us to Bruss’s concern with ‘the implied identity of author, narrator and protagonist on which classical autobiography depends’, and will enable us to see how this identity is manifested, and played with, particularly in relation to the other (non-authorial) subjects of the films. In a way that written autobiography can easily avoid, autobiographical film-making necessarily confronts the author/narrator, both with him/herself and with her/his ‘others’ (friends, family and any other characters in the films). My argument is that these confrontations invariably lead to a reflexive quality manifested in the films.

Confrontations along these lines are at the heart of The Alcohol Years (Morley 2000), Carol Morley’s film in which she retraced a missing period of her life when she had drunk herself into oblivion, by interviewing people she knew at the time. She does not appear in the film, but her interviewees talk directly to her (and us in the audience), looking into the lens of her camera, producing a curious sensation of the collapse into one another of the identities of author, protagonist and audience. This autobiographical use of the camera has profound consequences for the issue of ‘othering’. Morley’s previous alcoholic self is ruthlessly scrutinized (some of her interviewees being hurt by, and/ or critical of, how she treated them in her lost years), but we in the audience are made to experience the scrutiny almost as though it were us being judged, because the interviewees speak into the lens. The boundaries between subject and object, the authorial self and her ‘others’, are blurred and complicated.

This complication is a recurrent trope of many recent autobiographical documentaries. The film-maker is always ‘visible’ in relationship to the people he/she is filming, sometimes actually because s/he appears alongside them, sometimes metaphorically because his/her presence is registered from behind the camera (in similar ways as Morley’s was). Dennis O’Rourke’s documentary The Good Woman of Bangkok (1991) also makes use of the way in which the autobiographical film-maker relates to his/her subjects, but in a more troubling way. Linda Williams has described this as a ‘film about a Thai prostitute hired by the filmmaker to be his lover and the subject of his film’ (1999: 176) - a strategy by which, she points out, he ‘makes himself vulnerable to feminist wrath’ (1999: 176). However she goes on to ‘argue that that very vulnerability is also what makes this film so challenging to conventional documentary ethics’ (1999: 176-77). A large part of this vulnerability derives from the way his autobiographical camera exposes his relationship with Aoi (the prostitute):

Her speech to the camera (and thus to O’Rourke, who operates both camera and sound throughout the film) alternates between extremely factual accounts of the economics of her life [...], and extremely emotional accounts of her hatred of men [...]. She clearly condemns the patriarchal system that holds her in such thrall, and she astutely includes her relationship with O’Rourke as part of that system.

(Williams 1999: 180-81)

At the same time Williams applauds ‘O’Rourke’s effort to be ethical within an unequal situation - which is, after all, the situation that most men and women inhabit in the real world’ (1999: 185). His film is one of those ‘new forms of documentary practice that seem to have abandoned the traditional respect for objectivity and distance [.] in contexts fraught with sexual, racial and postcolonial dynamics of power’ (1999: 178).

In Elle s’appelle Sabine (Bonnaire 2007) Sandrine Bonnaire - the well-known French actor - filmed her autistic sister over many years as her disability worsened, and edits this footage together into a moving and intimate account of Sabine’s life and their relationship. Sabine’s disability sometimes manifested itself as an obsessive need for reassurance that Sandrine is not about to abandon her, or is returning the next day to see her, so that often she’s repeatedly addressing these kinds of questions directly to the camera: ‘When are you going?’ ‘Are you coming back tomorrow?’: and Sandrine is answering them, often with mounting exasperation, from behind the camera, which puts us, in the audience, into a virtual simulation of their relationship, not dissimilar to O’Rourke’s with Aoi in The Good Woman of Bangkok, or Morley’s with her friends in Alcohol Years. This works as well with scenes of joyful intimacy as with conflict. At one point towards the end of the film Sandrine shows her sister home-movie footage of a trip to the United States they made when Sabine was younger and less disabled. Sabine bursts into tears when she sees her younger self, telling the camera/Sandrine that they are ‘tears of joy’. The film is an instance of what Renov calls ‘domestic ethnography’:

In all instances of domestic ethnography, the familial other helps to flesh out the very contours of the enunciating self, offering itself as a precursor, alter ego, double, instigator, spiritual guide or perpetrator of trauma.

(2004: 228)

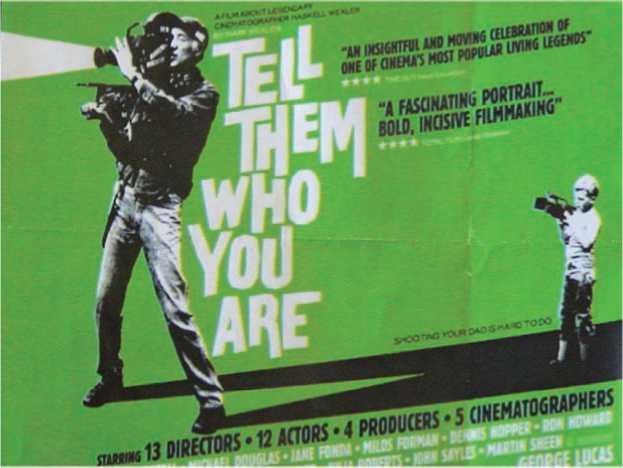

As Renov implies, the ‘familial’ or intimate ‘other’ in these films is frequently in conflict with the film-maker. In Alan Berliner’s Nobody’s Business (Berliner1996) - a portrait of his father - this conflict becomes the main narrative device of the film, which is structured around an abrasive interview by Berliner of his father, who is constantly on the verge of walking out because he considers his life ‘nobody’s business’ but his own. In Tell Them Who You Are (Wexler 2006) Mark Wexler also struggles to portray (and to reconcile himself with) his own father, the cinematographer and left-wing radical filmmaker Haskell Wexler.[5] Mark is clearly politically much more conservative: his best-known documentary up to the point he made Tell Them Who You Are was a celebratory film about Air Force One, the US Presidential airplane. However the differences between father and son are revealed as more than political, and are embedded into the structure of this film they are making together (often competitively filming each other). This Oedipal struggle is made clear in the poster for the film in which Mark appears as a little boy whose tiny video camera seems no match for his father’s 35mm machine: size is everything in this shoot-out:

Even so, Tell Them Who You Are ends with a touching reconciliation sequence in which Mark, shooting his father swimming in a pool, gives up the struggle and allows his father to direct the shot as he swims smiling towards the camera. The emotional resolution in the film is cleverly effected via a negotiation about how the scene is to be photographed - a sequence enabled by the relationships made possible in self-shot autobiographical documentary: their reconciliation is reflexively expressed.

Sometimes the ethics of these encounters with ‘familial others’ through the camera are less clear-cut. In Tarnation (Caouette 2004) Jonathan Caoutte makes a portrait of himself alongside a very emotional account of his relationship with his mother, who spent all of his life with her going in and out of Mental Health institutions. The film includes a couple of long sequences where he films his interactions with her when she is clearly in states of obvious distress and extreme confusion - which he does with himself too in a tearful piece to camera towards the end of the film. Nevertheless he has been critiqued[6] for transgressing the boundaries of the ‘home movie’ – making public what was intended to be private and domestic, and could equally be called to account for exploiting his mother when she was clearly completely unable to give lucid consent to the filming process. However, the quality and impact of these sequences - the raw, touching openness and vulnerability of Caoutte’s mother - are clearly the result of her relationship to her son and his autobiographical, observational camera.

The issue of obtaining the consent or even collaboration of the films’ other subjects for the autobiographical film-maker is complex - and often visible in the film as we saw with Berliner and Wexler above. It is a noticeable feature of the films of Ross McElwee how often his friends and partner ask him to stop shooting and turn off his camera. The voyeuristic power over their subjects that all documentary film-makers possess is rendered much more obvious in these films by the often inevitable reflexivity of the shooting situation. In Flying: Confessions of a Free Woman (Fox 2006) - a 6x1 hour series Jennifer Fox made for television, she explores a way of deconstructing this voyeuristic power. She had two main aims in making the series: the first was to break through her feeling when she started filming that she was in a crisis of ‘modern female identity (I cannot see my life)’,[7] and the second was to explore these feelings with women family members and women friends to find out ‘how women speak when men aren’t around’, and whether the feeling of sharing she experienced with her friends would be there in different parts of the world. She shot 1600 hours of material over five years about her own and her international group of women friends’ attitudes to sex and relationships, by doing self-filmed pieces to camera (on every day she filmed) as well as by using a technique she calls ‘passing the camera’. In conversations with individuals and groups of friends and women she had just met, she would (with some minimal instruction) pass the camera to someone else if she had something to add to the conversation. In these ways some of her voyeuristic power was diminished and she was able to make herself appear (as a subject of the film-making process) as equally open and vulnerable as the other women she was filming (despite her being in editorial control). As some critics have pointed out, there are issues with the film’s ‘western focali- zation’ (her ‘correlation between orgasm and emancipation’ which leads to misunderstandings in her dealings with non-western subjects) and with her apparent omission of ‘lesbian desire’. Nevertheless the film - with its passing the camera technique - does hold ‘up to the West a painfully honest mirror of its own confused encounter with [...] cultural difference’ (Fenner 2012: 137).

Clearly Fox’s techniques in Flying were very dependent on being able to generate footage on low cost, lightweight and easy-to-use video equipment. The advent of the camcorder has enabled a new aesthetic in autobiographical film-making, that of the ‘video-diary’, which has itself become a new ‘jargon of authenticity’ (Arthur 1993):

Everything about it, the hushed whispering voiceover, the incessant to-camera close-up, the shaking camera movements, the embodied intimacy of the technical process, appears to reproduce experiences of subjectivity. We feel closer to the presence and process of the filmmaker.

(Dovey 2000: 57)

Agnes Varda revels in this intimate use of the camcorder in The Gleaners and I (Varda 2000), celebrating it as one more instance of ‘gleaning’, in the way it enables her to hoover up images with ease as she travels, like the gleaners in the wheat fields in Millet’s painting Les glaneuses, whom she talks about at the beginning of the film. She enthuses on the soundtrack ‘these new small cameras, they are digital, fantastic, narcissistic, and even hyper-realistic’ and she exploits the potential of her camera as a tool for self examination, ‘gleaning’ images of herself as she points it at the wrinkled skin on her hand. The film becomes a self-portrait and meditation on ageing and death, counterpointing the social critique of poverty and waste that is the main theme of the film. In a number of sequences she reminds us of the physicality - ‘the embodied intimacy - of her use of the camcorder, for instance as she drives along the motorway filming her own hand again, curling round and playfully ‘grabbing’ lorries as they pass her on the motorway.

This home-made aesthetic, made possible by the camcorder, is a large part of its appeal for documentary makers. In comparison to film, video is cheap and accessible: for instance, the production of Tarnation (Caouette, 2003 - described above) was wholly dependent on developments in low-cost video technology in a number of respects. A lot of the footage was originally shot by Caouette in his childhood on various domestic formats, which he then edited together with contemporary diary and impromptu, intimate observational footage, on iMovie, Apple’s domestic editing programme. This first cut, before the film was taken up by distributors and shown at the Cannes Film Festival, cost a total of $213.72.[8] Other video artists in the United States, before Caouette, have exploited the accessible, domestic intimacy of the new video technologies in similar ways - notably Sadie Benning, George Kuchar and Wendy Clarke.

Benning’s tapes from the early 1990s [9] (when she was a teenager) made use of an early ‘toy’ video camera made by Fisher Price, that, in Russell’s words, ‘produced such a low definition image that it became known as pixelvision’. Russell goes on to remark:

Because pixelvision is restricted to a level of close-up detail, it is an inherently reflexive medium [...] The ‘big picture’ is always out of reach, as the filmmaker is necessarily drawn to the specificity of daily life.

(1990: 291)

Benning’s tapes were often made in the privacy of her bedroom, and explored, amongst other themes, her coming out as a young lesbian. This same quotidian intimacy is a feature of George Kuchar’s video diaries,[10] again according to Russell:

He creates the impression that he carries the camera with him everywhere, and that it mediates his relation with the world at large. [.] The camera is explicitly situated as an extension of his vision, but also of his body. In close-ups of food or of himself, the proximity of the profilmic to the lens is defined by the length of his reach.

(1999: 286 and 289)

Russell summarizes Benning’s and Kuchar’s video diaries as representing

their bodies in space. The camera as an instrument of vision serves as a means of making themselves visible, a vehicle for the performance of their identities. [.] Video provides a degree of proximity and intimacy that enables this spatialization of the body. Instead of a transcendental subject of vision, these videos enact the details of a particularized, partialized subjectivity.

(1999: 294-95)

Self-shooting, autobiographical documentary can be very ‘political’ as well as personal (as Varda demonstrates in ‘The Gleaners ...'), and can use its ‘particularized subjectivity’ to illuminate wider social issues.

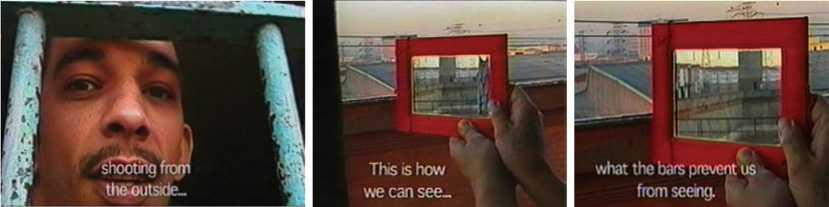

The Prisoners of the Iron Bars (Sacramento, 2003) is a Brazilian featurelength documentary in which the film-makers gave inmates camcorders to record their own view of life in Carandiru, a notorious prison in the city of Sao Paulo. In one sequence ‘The night of an inmate’, the film features the occupants of one particular cell, trying to, in their words, ‘show you about this place, especially at night ... It’s hard with words. Maybe it works with images, right?’. The sequence conveys an impression of the lives of these prisoners that would have been impossible other than in the video diary form. The prisoners film their morning and evening routines, photos of their families and homes, distant commuter trains passing, and fireworks exploding far away in the dark night outside their cell window. They show how they communicate with a woman in a block of flats opposite the prison, using hand signals, and, in a remarkable scene from the early morning, how they use a mirror to extend what they can see outside their cell window:

It is the way in which the self-shooting camera is used that makes the point about the restrictions of prison life.

A more recent instance of a highly political autobiographical documentary is 5 Broken Cameras (Burnatt & Davidi 2011), co-directed by a Palestinian, Emad Burnat, and an Israeli, Guy Davidi. 5 Broken Cameras is an autobiographical account of encroaching Israeli settlements and the resistance to them in a West Bank village, shot almost entirely by Burnat, who bought his first camera in 2005 to record the birth of his youngest son. The film features the destruction of each of Burnat’s five cameras, either shot or smashed as a result of his participation in the resistance - which, of course, we in the audience get to witness directly as Burnat is mostly holding the camera himself as these incidents happen. The political weight of the film is somehow added to, I think, by virtue of the cameras being used autobiographically in Burnat’s domestic space - to record his family, as well as his wife’s apprehensions about his filming and political activities, as well as on the public demonstrations.

So there is a clear political significance of the autobiographical project - as L. Rascaroli expresses it - ‘to speak “I” is, after all, firstly a political act of self-awareness and self-affirmation’ (2009: 2) - or as Renov says:

‘who we are’, particularly for a citizenry massively separated from the engines of representation - the advertising, news, and entertainment industries - is a vital expression of agency. We are not only what we do in a world of images: we are also what we show ourselves to be. [...] autobiography has become a crucial medium of resistance and counterdiscourse [...].

(Renov 2004: xvi)

I hope I have shown that the radical potential of autobiographical documentary derives not only from ‘what we show ourselves to be’ but also from the relationship between ‘seer and seen’ - how we show ourselves with our cameras: it’s this self-shooting reflexivity that helps create - and is a crucial element of - the ‘counterdiscourse’.

References

Adams Sitney, P. (1978), ‘Autobiography in avant-garde film’, in P. Adams Sitney (ed.), The Avant-Garde Film, New York: New York University Press, pp. 199-246.

Arthur, P. (1993), ‘Jargons of authenticity (three American moments)’, in M. Renov (ed.), Theorising Documentary, New York and London: Routledge.

Astruc, A. ([1948] 1968), ‘The birth of the new avant-garde: La CameraStylo’, in P. Graham (ed.), The New Wave, London: Secker & Warburg, pp. 17-23.

Berliner, Alan (1996), Nobody’s Business, New York: Cine-Matrix.

Bonnaire, Sandrine (2007), Elle S'Appelle Sabine Betheny: Mosaique Films.

Burnat, Emad & Davidi, Guy (2011), 5 Broken Cameras, Paris: Alegria Productions.

Brink, J. Ten (2007), ‘From Camera-Stylo to Camera-Crayon et puis apres ...’, in J. Brink, Ten (ed.), Building Bridges: The Cinema of Jean Rouch, London: Wallflower Press, pp. 235-248.

Broomfield, Nick (1991), The Leader, His Driver and The Driver’s Wife, Santa Monica CA: Lafayette Films.

Broomfield, Nick (1998), Kurt and Courtney, London: BBC/Strength Ltd.

Broomfield, Nick (2003), Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer, Santa Monica CA: Lafayette Films.

Bruss, E. (1980) ‘Eye for I: Making and unmaking autobiography in film’, in J. Olney (ed.), Autobiography: Essays Theoretical and Critical, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 296-320.

Bruzzi, S. (2006), New Documentary, London: Routledge.

Caouette, Jonathan (2003), Tarnation, London: BBC Storyville.

Czach (2012), ‘From Repas de bebe to Tarnation’ interin.utp.br/index.php/ vol11/article/download/147/132. Accessed 20 January 2013.

Darke, C. (2003), Chris on Chris - An Insight Into Chris Marker (DVD Extra Features), Glasgow: Nouveaux Pictures./Moviemail.

Dovey, J. (2000), Freakshow: First Person Media and Factual Television, London: Pluto Press.

Egan, S. (1994), ‘Encounters in camera: Autobiography as interaction’, Modern Fiction Studies, 40: 3, pp. 593-618.

Fenner, A (2012), ‘Jennifer Fox’s transcultural talking cure’, in A. Lebow (ed.), The Cinema of Me, New York/Chichester: Wallflower, pp. 121-143.

Fox, Jennifer (2006), Flying: Confessions of a Free Woman, New York: Zohe Film Productions.

Lane, J. (2002), Autobiographical Documentary in America, Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Lucia, C. (1994), ‘When the personal becomes political: An interview with Ross McElwee’, Cineaste, 20: 2, pp. 32-37.

McElwee, Ross (1986), Sherman’s March, Cambridge MA: Homemade Movies McElwee, Ross (1994), Time Indefinite, Cambridge MA: Homemade Movies.

— — (1996), Six 0’Clock News, Cambridge MA: Homemade Movies.

— — (2003), Bright Leaves, Cambridge MA: Homemade Movies.

MacDougall, D. (1998), Transcultural Cinema, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

McLaughlin, C. and Pearce, G. (eds) (2007), Truth or Dare: Art and Documentary, Bristol: Intellect Books.

Minh-Ha, T. T. (1991), When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender, and Cultural Politics, London: Routledge.

— — (1992), Framer Framed, London: Routledge.

Moore, Michael (1989), Roger and Me, New York: Dog Eat Dog Films.

Morley, Carol (2000), The Alcohol Years, London: Cannon and Morley Productions.

O’Rourke, Dennis (1991), The Good Woman of Bangkok, Canberra: O’Rourke & Associates Filmmakers.

Rascaroli, L. (2009), The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film, London: Wallflower Press.

Renov, M. (2004), The Subject of Documentary, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Russell, C. (1999), Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video, Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Sacramento, Paolo (2003), Prisoner of the Iron Bars, Rio de Janeiro: Olhos de Cao Produces Cinematograficas.

Sherwin, S. (2004), Guardian Film and Music Supplement, 21 May, pp. 8-9.

— arda, Agnes (2000), The Gleaners and I, Paris: Cine Tamaris.

Williams, L. (1999), ‘The ethics of intervention: Dennis O’Rourke’s The Good Woman of Bangkok’, in J. M. Gaines and M. Renov (eds), Collecting Visible Evidence, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 176-89.

Suggested Citation

Dowmunt, T. (2013), ‘Autobiographical documentary - the “seer and the seen”’, Studies in Documentary Film, 7: 3, pp. 263-277, doi: 10.1386/sdf.7.3.263_1

Contributor Details

Tony Dowmunt is a Senior Lecturer and the Course Convenor for M.A. Screen Documentary at Goldsmiths, University of London. From 2003 to 2006 he had an AHRC fellowship in the Creative and Performing Arts, which included the production of an experimental video-diary, A Whited Sepulchre. Before that he worked in television documentary production for 25 years, as well as pursuing an interest in community-based video and social-action media.

He has written extensively in the latter area, including writing articles and editing three books - The Alternative Media Handbook (Routledge, 2007), Inclusion through Media (Goldsmiths/Equal, 2007) and Channels of Resistance: Global Television and Local Empowerment (BFI, 1993).

Contact: Department of Media & Communications, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK.

E-mail: t.dowmunt@gold.ac.uk

[1] Interview with Doug Block, The Ross McElwee Collection DVD, First Run Features 2006.

[2] Interview with Doug Block, The Ross McElwee Collection DVD, First Run Features 2006.

[3] Interview with Doug Block, The Ross McElwee Collection DVD, First Run Features 2006.

[4] These film-makers seem to be invariably male, and the films are consequently highly ‘gender inflected’ (Dovey 2000: 27).

[5] Haskell Wexler is well known for directing Medium Cool (1969) a ‘docu-drama’ about the 1968 Chicago Democratic convention.

[6] For instance by Liz Czach (2012).

[7] These statements and those that follow were all made by Fox at a ‘Masterclass’ with the film-maker I attended at the ICA, London, February 2008.

[8] According to Caouette himself in an interview (Sherwin 2004) he estimated the final costs, after all the postproduction processes needed to put it into distribution, were going to be ‘just under $400,000’ (Sherwin 2004).

[9] Her work is distributed by Video Data Bank: www.vdb.org/smackn.acgi$artistdetail?BENNINGS

[10] His work is distributed by Electronic Arts Intermix: www.eai.org/eai/artistTitles.htm?id=313, accessed 6 November 2009.