Erana Jae Taylor

Tsuji Jun (original edition)

Japanese Dadaist, Anarchist, Philosopher, Monk

I. Introduction: About This Work

Significance, Purpose, Avenues for Future Research

A Necessarily Interdisciplinary Approach

To Write in an Increasingly Oppressive Climate

From “Tsuji Jun and the Teachings of the Unmensch”

An Overview of PreWar Japanese Anarchism

IV. Dada as a Reflection of Das Gleitende

Rationalism in Austria, Meiji Japan

Das Gleitende Outside of Vienna

Dada: Tsuji’s Philosophical Nexus

Art as a Social and Political Medium

The Private as Public and Living Life as an Artform

Dada, Stirner’s Anarchism, and Buddhist Nothingness

Tsuji’s Translations and Literary Influences

Tsuji’s Dadaism, Takahashi’s Dadaism

Tsuji Jun in the late 20th and early 21st Century

Appendix I: Major Translations

Appendix II. A Review of Supporting Literature

TSUJI JUN: JAPANESE DADAIST, ANARCHIST, PHILOSOPHER, MONK

by

Erana Jae Taylor

A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the

DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES

In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements

For the Degree of

MASTER OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES

WITH A MAJOR IN JAPANESE LITERATURE

* * *

The University of Arizona

2010

Statement by Author

This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgement the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author.

SIGNED: Erana Jae Taylor

Approval by Thesis Director

This thesis has been approved on the date shown below:

SIGNED: _______

Philip Gabriel, Department of East Asian Studies

Acknowledgements

I’d like to extend my thanks to:

Philip Gabriel for chairing my committee as well as ...

Barbara Kosta ... for her kindness

Chris Rowe ... for his humanity

David Ortiz ... for existing

John Olsen ... for more than words can say

Mark Unno ... for being spunky

Mum ... for her supportiveness

... and to all who have contributed to scholarship on Tsuji Jun.

* * *

[Dedication]

This work is dedicated to those who live with the heart as their authority

Table of Contents

ABSTRACT ... 7

I. INTRODUCTION: ABOUT THIS WORK

Significance, Purpose, Avenues for Future Research ... 8

A Necessarily Interdisciplinary Approach ... 11

Problems With this Research ... 13

The Gleitende Focus and Key Terms ... 14

II. THE LIFE OF TSUJI JUN

A Life History ... 19

To Write in an Increasingly Oppressive Climate ... 26

Personality & Lifestyle ... 28

From “Tsuji Jun and the Teachings of the Unmensch”. 31

III. BACKGROUND & CONTEXT

An Overview of PreWar Japanese Anarchism... 33

On Nihilism in Japan ... 38

Egoism as a Form of Nihilism ... 38

Relation to Darwinism ... 39

Stirnerism in a Nutshell ... 44

On Dada in Japan ... 47

Dada’s Relation to Ero Guro Nansensu ... 50

Contemporaries of Tsuji Jun ... 51

Mavo ... 51

Yoshiyuki Eisuke ... 52

Hagiwara Kyōjirō ...

53 Takahashi Shinkichi ... 55

Kaneko Fumiko ... 56

Ōsugi Sakae and Itō Noe ... 57

IV. DADA AS A REFLECTION OF DAS GLEITENDE

Rationalism in Austria, Meiji Japan ... 60

Das Gleitende Outside of Vienna ... 65

V. THE DADA CONNECTION

Dada: Tsuji’s Philosophical Nexus ... 68

Art as a Social and Political Medium ... 70

The Private as Public and Living Life as an Artform.. 75

Dada, Stirnerism, & Buddhist Nothingness ... 78

VI. THE WORK OF TSUJI JUN

Tsuji’s Translations and Literary Influences ... 85

Tsuji’s SelfPerception ... 88

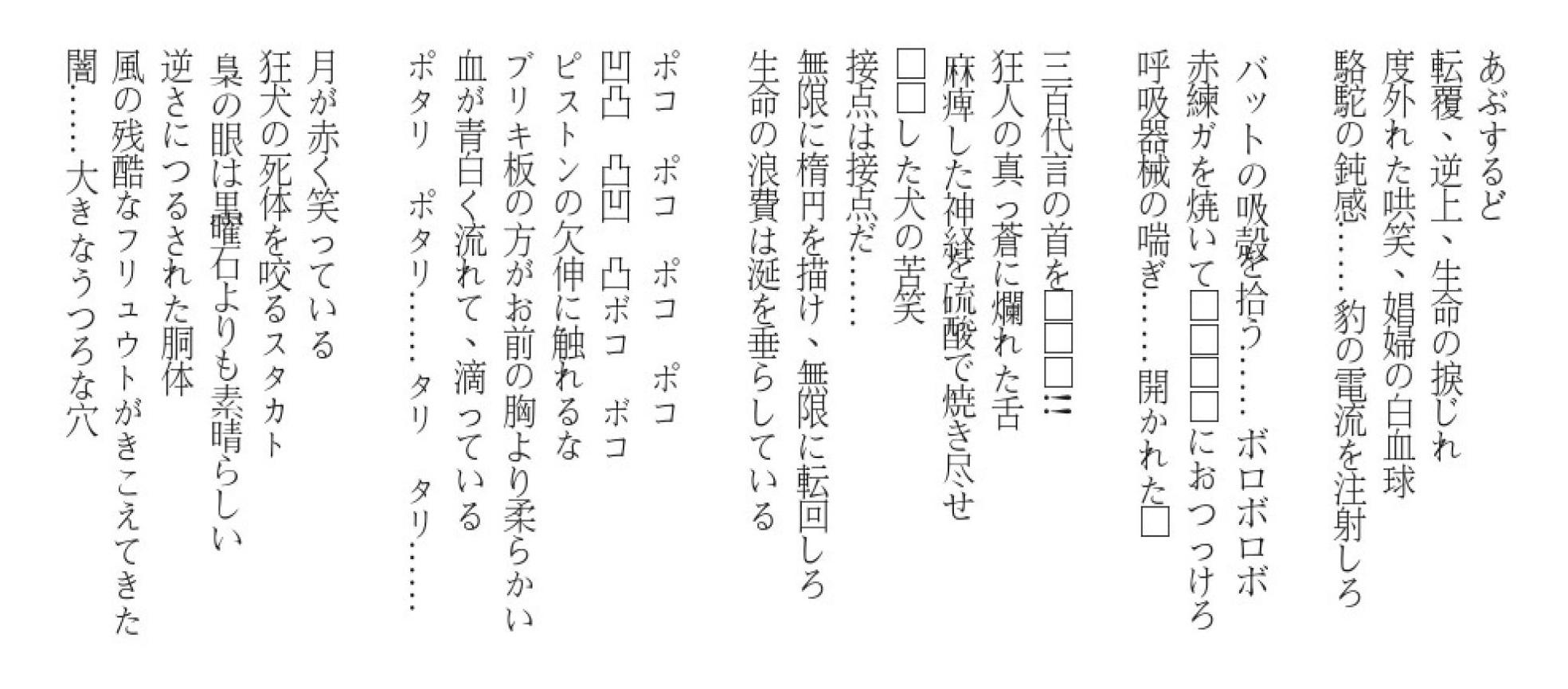

Poetry Sample: “Absurd” ... 91

Tsuji’s Dadaism, Takahashi’s Dadaism ... 96

Reception ... 96

VII. CONCLUSION

Tsuji Jun in the late 20th and early 21st Century ... 99

Hope versus Despair ... 101

APPENDIX I: MAJOR TRANSLATIONS ... 104

APPENDIX II: SUPPORTING LITERATURE ... 105

Secondary Literature ... 105

Works by Tsuji ... 107

A Three Piece Sample of Japanese Works on Tsuji ... 108

REFERENCES ... 111

Abstract

Tsuji Jun (1884 – 1944) was the selfdeclared first Dadaist of Japan and was the most prominent advocate of literary Dada there. He is known for having translated Max Stirner’s The Ego and Its Own and for having been the husband of anarcho-feminist Itō Noe. However, until now, little else has been written about him in English despite voluminous Japaneselanguage scholarship.

As an Anarchist, Nihilist, Dadaist, poet, and monk he is a striking character among contemporary Japanese historical figures. Even more intriguing is Tsuji’s writing, marked by a fusion of Buddhist, Dadaist, and Nihilist philosophy. The present work regards his life, work, and relation to his contemporary writers, and summarizes his philosophy. This is done in the context of the growing scepticism towards Rationalism in Meiji/Taisho Period Japan, describing the relationship this has with what in 1905 Hugo von Hofmannsthal termed das Gleitende (the “slippage”) of turnofthecentury Vienna.

I. Introduction: About This Work

Significance, Purpose, Avenues for Future Research

Though he is widely recognized in English, German, and Japanese scholarship as the prime establisher of Dadaism in Japan, there is a lack of substantial English literature about a most fascinating of historical figures, Tsuji Jun[1]. In spite of this, at the time of this writing there exist at least ten substantial works of scholarship in Japanese that are focused expressly on him.

Tsuji’s story is not, however, strictly a story about an eccentric Japanese. One cannot properly speak of Nihilism, Egoism, or literary Dadaism in Japan for any length of time without mentioning Tsuji’s place in that continuum. To lack Englishlanguage[2] scholarship on Tsuji leaves open a gap in not only understanding the Japanese avantgarde arts movement but also in the consequences of Germanic art, literature, and philosophy on a global scale.

While Dadaism was originally an importation into Japan from Europe, it began to blend with concurrent Japanese culture (including Buddhist ideas) almost immediately. Over time this created a whole new body of literature with a Buddhist aspect that has only been significantly explored in Englishlanguage texts in the context of a single individual, Takahashi Shinkichi.

While several academics have recognized the intersections between Nihilism and Buddhism in Japan (Nishitani, Parkes, Unno) there is a dearth of scholarship that deals with how this interfaced with the Anarchist and Dadaist movements in Japan that were so linked to Nihilism. Therefore, an important question becomes “what relationship did Buddhism have with the nihilistic elements of the Anarchist and Dadaist movements in Japan?” While this is covered to some extent by Won Kŏ ‘s parallel work on Takahashi Shinkichi, the present work will attempt to answer this question in regards to Tsuji’s take on Dadaism in chapters V and VI.

Indeed, Takahashi’s Dadaism was distinct from Tsuji’s, and Ko makes the correct observation that Tsuji’s ideas of Dadaism were rooted in Egoistic Nihilism[3], whilst Takahashi favoured a more expressly Buddhist take on Dada and became disenchanted with Stirner in light of his finding “a great gulf of contradiction fixed between the two [Egoism and Buddhism]”[4].

Regardless, there remains a definite Buddhist tint to Tsuji’s body of work and it is conceivable that Tsuji would have disagreed with Takahashi’s conception of Egoism and Buddhism being incompatible philosophies, especially during the middling years of his life. Rather, Tsuji’s Egoism contained a great deal of Epicurean idealism for thoroughly enjoying a simple life, which complemented Tsuji’s Buddhist objective of reducing (his own) suffering.

Late in life Tsuji gave up on Dadaism after an apparent mental breakdown, whereafter he became a wandering Buddhist monk. Takahashi also turned to Buddhism after Dadaism, though Tsuji does not seem to have renounced Egoism explicitly as Takahashi did. After his institutionalization, Tsuji remarked, “Since life isn’t very long, I [still] just want to manage an ordinarily peaceful and innocent life. It’s just that my experiences up until now have shown me that’s not so easy to do”[5]. This statement would prove an unfortunate foreshadowing of the difficulties he would continue to experience for years afterwards as he struggled to maintain sanity.

Both Takahashi and Tsuji tried to use Dadaism in their personal and philosophical pursuits of human freedom, though Takahashi utilized an approach more grounded in the Japanese tradition of Zen and Tsuji attempted a more philosophical approach reminiscent of the German philosophers. While Tsuji wrote voluminously to this end, Tsuji himself attempted to express his philosophy foremost through his own lifestyle, as remarked upon by Hagiwara Kyōjirō.[6] As a result, much of Tsuji’s philosophical literature comes out through autobiographical explanations of his own experimentation in art and lifestyle.

Another central question laid out in this work concerns the role of Dada and affiliated philosophies during the process of Japan’s Meiji/Taisho Period modernization and Modernism, which is discussed in Chapter IV in the context of a breakdown of Rationalism.

The most overarching purpose of this work, however, is to briefly introduce Tsuji Jun to the English-speaking academic world with the hopes that it will encourage further research on him and related topics.

A Necessarily Interdisciplinary Approach

While applying the term “polymath” would be an exaggeration, Tsuji at once managed to be a translator of a large body of work, an avid reader and patron of the arts, a wellknown essayist and philosopher, a musician, a poet, an actor and playwright, a painter, and a calligrapher. Dada as a medium must have suited Tsuji tremendously well because of the unlimited mediums Dada can be implemented in and the overlaps that occur between Dadaism and other philosophies.

The fertile interdisciplinary nature of Tsuji’s interests is part of what makes him such an fascinating topic, and this breadth lends itself to any number of angles for study. Surely this is a contributing factor as to why so many Japanese have chosen to write about him, each wanting to tell Tsuji’s story from their own angle. As a result we find titles ranging from Nihilist: the thought and life of Tsuji Jun; Love for Tsuji Jun (a lover’s memoir); Nomad Dadaist Tsuji Jun; Madman Tsuji Jun: a shakuhachi flute, the sound of the universe, and the sea of Dada; and Tsuji Jun: Art and Pathology[7], among others.

While the breadth of his interests and the variety of approaches taken in scholarship about him make a study of him challenging as well as rewarding, one cannot grasp this content without taking an international angle. After all, with Tsuji being a major reader and translator of various foreign literatures (German, English, Italian, and French[8]), it is essential to place him in the context of his Western peers.

To better grasp this internationalism of his would be to better understand the transnational exchange of thought and culture during early modern Japan. In the shadow of today’s perpetual discussion of globalization, it is often a neglected fact that intercultural blending had been significant long before the Internet and globalization came about as we know them today.

Unfortunately the spatial limitations of this work prevent an analysis of this international exchange on any thorough level and focuses instead on other topicsbut this leaves open for future scholarship comparisons between Tsuji and various European thinkers, as well as a more indepth explanation of the depth of impact had on Tsuji by German thinkers (Nietzsche, Stirner, and the Dadaists) and the impact Tsuji may have had on other thinkers while he was abroad. While I am not suggesting that other international influences were unimportant to what Tsuji would become, this work is definitely rooted in the Germanic slant to Tsuji’s literature. It is especially biased towards the (truly substantial) influence of Max Stirner.

As an introductory work to an interdisciplinary topic, to have any significant grasp on the life and works of Tsuji Jun and the historical context surrounding him, an interdisciplinary approach is imperative. This is especially because, once one gets deep into the literature and life of Tsuji Jun, there are no effective boundaries of where one of these disciplines begins and another ends, which is a characteristic that marks Dada itself. The interdisciplinarianism of Dadaism and Tsuji’s work provides excellent evidence for the necessity of disciplinary boundaries between departments at scholarly institutions to remain permeable.

Problems With This Research

This work’s approach of addressing a few keystone ideas shared across disciplines derives from an effort to do enough justice to each of these adjacent realms while maintaining a firm coherence. However, Tsuji’s work has enough amorphous area between disciplines that one is left wondering where to begin, let alone how to speak of such concepts without seeming redundant by having to continually rereference the conjoining fields whenever they recur.

Another problem caused by this interdisciplinarianism is that its assumes so many topics that the amount of background one must provide is multiplied by the number of topics, thereby reducing the amount of space available for more penetrating and complex analyses. This work aims at a general overview in biographical, historical, political, philosophical, thespian, and literary veins. I would encourage readers to further develop their background through external reading in any areas they feel are inadequately explained here. On the bright side, the thinness of this overview leaves a lot of potential for future scholarship on the topic. However, the author will forever be disappointed in the impossibility of thoroughly conveying here the wondrous depth of this topic.

Key Terms

The Germanic connection to Tsuji’s story is clear when it comes to the literary influence of Germanic writers such as Stirner, Nietzsche, and the German Dadaists, but one must also look to the historical context of these writers as an influence upon internationally sensitive individuals such as Tsuji. Unfortunately this background is also largely omitted here. Because there have been any number of books written on the historical context of European Dadaism and philosophy, this work will focus predominantly on Japan’s place in this intellectual scene. This portion will fall mostly in Chapter IV through the Gleitende focus that is used there to describe the decay of Rationalism in Japan during Tsuji’s lifetime. The term das Gleitende is examined there.

The Japanese terms mu (無), muga (無我), and kū (空) refer to concepts that have been used in describing Nihilism’s quality of “nothingness” in a variety of ways.[9] The term kū is a particularly Buddhist term that refers to “emptiness”, usually along with the phrase “all things are ‘empty’”. For Nagami Isamu[10] this implies that nothing has an unchanging form or “essence”, as though any given thing is like an empty vessel that can be filled with some temporary form. He explains that this emptiness is evident in the changing nature of all things in the world.

Some, including Nietzsche, have argued for the similarity of kū to the Nihilistic assertion that all things are empty of inherent meaning and are only “filled” with meaning when there is someone to create that meaning through the act of making a judgement about that thing. On the other hand, some argue that this approach is a mistake[11], presumably because the emphasis to the Buddhist kū is a thing’s lack of an unchanging form, whereas the emphasis to Nihilism’s emptiness is that meaning is a construct of the observer as a result of their drives[12]. However, it could also be argued that regardless of their rationales, both philosophies are still arguing that things lack inherent essences or meanings.

The term mu is best translated as “nothing”, “nonbeing”, or “non” and does less to imply the existence of some vessel containing the emptiness. However, the character for kū is the same as the character for sora or “sky” (a trait often manipulated by poets), the imagery of which does not much imply a vessel. Thus, the point of the term kū is arguably to express emptiness rather than emptiness within a vessel, but the author prefers the term mu because it is less likely to be interpreted in this way.

Conversely, mu is a more flexible term because it simply implies a lack of something, especially because it often appears as a prefix to negate the meaning of a suffix in Japanese. For example, the term mugon no (無言の) signifies that something is silent, mute, or tacit, where the second character implies speech and the first, mu, implies the lack thereof. The incorporation of this power to negate makes the meaning of mu seem closer to Nietzsche’s original meaning of “Nihil”, which also incorporates the concept of negation[13].

Mu stands as the opposite of u (有), or “being”. However, Abe Masao asserts that mu and u are completely reciprocal and that mu is not derived from u the way that nichtsein is derived from sein (186). His point is that there must be a distinction made between relative mu (the opposite of u) and absolute Mu (“true Emptiness” or Śūnyatā, the spiritual realization of which would be transcendent of even the negation of u into mu or vice versa).

Kūkyo (空虚) is another term that means emptiness, combining kū and the kyo (hollow) from kyomu (虚無) (both of which Tsuji uses in his work)[14]. Kyomu combines mu and kyo and is used to indicate nihility, or the sense of emptiness implied specifically by Nihilism. The characters kū and kyo are basically interchangeable in the word utsuro (空ろ, 虚ろ), which Tsuji uses in “Absurd” in Chapter VI in the context of a great void, which itself could be interpreted as Nirvana or as death.

The semantical accuracy of the words mu, Mu, kū, etcetera in regards to Nietzsche’s and Stirner’s conceptions of nothingness is debatable, and while this writing makes use primarily of the term mu because of its usefulness in both Nihilist and Buddhist connotations, readers are encouraged to consider similarities between the two philosophies’ conceptions of nothingness in whatever terms best suit them. This work’s use of mu is intended less to pinpoint the exact relationship between the two philosophies, and is more intent on developing a historical account which indicates that Buddhist associations have been applied to Nihilism in Japan much the same way Dada received the same Buddhist associationsboth from their very first introductions[15].

Another term that finds use in discussions of nothingness between Japanese Buddhism and Nihilism is muga, or “noself” / “noego” (anattā). This is also addressed in Ko’s work on Takahashi[16]. In this work, muga is an important point of contention between Buddhism and Nihilism. While both philosophies have overlapping conceptions of “nothingness”, muga presents a major distinction that reminds us of how they have different approaches for dealing with their common struggle for human freedom.

That is, Buddhism’s imperative is to dismantle a sense of ego to extinguish suffering (dukkha) by realizing nothingness, whereas (Stirnerist) Nihilism apotheosizes the role of the ego to enhance life and free one from limitations imposed by a lack of understanding of nothingness.[17] It is the nothingness itself, rather than the approaches or consequences, that this work asserts that Nihilism and Buddhism have in common. This commonality is expressed in Tsuji’s philosophy, as expressed throughout this work. The divergence of the philosophies’ approaches is what most severely divided the philosophies of Tsuji and Takahashi while they were Dadaists, who had both been influenced by Buddhism and Nihilism.

II. The Life of Tsuji Jun

A Life History [18]

Tsuji Jun (also known during his later years as Mizushima Ryūkitsu) was born the fourth of October, 1884 in Asakusa, Tokyo, and died at the age of 60 on November 24th, 1944[19]. He was born the eldest son of a lowranking government official and attended Kaisei Junior High School until the age of 12, whereupon his family’s finances declined, forcing him to begin working as an office boy and taking classes at night. According to Tsuji, his youth was “nothing but destitution, hardship, and a series of traumatizing difficulties”.[20] To escape from this hardship Tsuji embraced literature, particularly classical Japanese literature (Hōjōki, Tzuzuregusa) and the romantic thrillers of Izumi Kyōka. Literature would remain of extreme, lifelong importance for him.[21] [22]

In 1899 he began to study English at a foreign language school, where he also was introduced to Christianity. He would study the Bible and the publications of the prominent Christian figure, Uchimura Kanzō, though this interest was not to be a lasting passion.[23] Later, he began to learn French and became interested in Tolstoyan Humanism and Christian Socialism.[24] Eventually he was able to land a job as an elementary school teacher in 1903. With his interest in socialism deepening, he subscribed to Kōtoku Shūsui’s Heimin Shimbun (Commoner’s Newspaper) and began integrating into a circle of anarchist friends.[25]

In 1909 Tsuji began teaching English at an allgirls high school while doing ontheside translation (Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Bell”, “The Shadow” [1906, 1907], Guy De Maupassant’s “The Necklace” [1908]). In 1912 a love affair developed between Tsuji (28 years old) and his pupil, Itō Noe (17 years old), resulting in his resignationafter which he would continue to be unemployed (not counting freelance work) until the end of his life. Rather, this former teacher of Itō, a fervent feminist, would strive to “cultivate her to the limits of woman’s possibilities. I’ll drag out of her every talent and gift dormant within her. I’ll definitely make her into a wonderful woman by pouring into her all my knowledge, even my life”.[26] Ironically, Tsuji’s feminist ideal of the empowered “new woman” in practice was that of a woman heavily dependent on male power and charity.

According to Tsuji’s essay “Humoresque”, Tsuji was charmed by Itō’s literary talent and countrygirl beauty. He even goes as far as calling her way of speaking “like that of a bumpkin”.[27] Itō had been in a difficult arranged marriage from which she wished to escape, the attempt at which provoked controversy regarding a perceived romantic relationship developing between the two. From the time of Tsuji’s resignation Itō came to live in Tsuji’s house and the family would endure increasingly impoverished conditions because of the loss of Tsuji’s job. Tsuji and his mother would quietly pawn their possessions onebyone to keep it a secret from Itō.[28] It was also in this year, 1912, that Tsuji began reading Stirner’s The Ego and its Own. Shortly thereafter Itō would begin contributing to Seitō (Bluestockings[29]). The household made ends meet through earnings from Seitō and Tsuji’s piecemeal translation work.

Itō would have Tsuji’s first son on January 20th 1914, named Tsuji Makoto, who later would also become known for his poetry and artwork, which often depicts rural scenes in a fashion generally critical of civilization. About the time of Makoto’s birth, Tsuji’s translation of Lombroso’s work The Man of Genius (a book about lunacy and prodigies) became a bestseller, and Itō Noe became chief editor of the nowrenowned feminist publication Seitō.[30] During these early years together, because Tsuji had lost his job, Tsuji found himself suddenly able to, without having to worry as much about consequences, experiment with the egoistic lifestyle he had thought so highly of while reading Stirner. As such it was a period of important personal transformation as he attempted to divine what he really wanted to do with himself and what socialized behaviours he did not really wish to adhere to.[31]

Tsuji encouraged Itō’s selfdevelopment most notably by frequently helping her with translations and editing her articles for Seitō, as well as providing encouragement in the process of becoming “the new woman” (a feminist ideal of the liberated female, as discussed in various issues of Seitō).[32] He also introduced her to a number of texts that would be formative for her, including the work of Emma Goldman.[33] Not long afterwards, Tsuji and Itō began spending time with Ōsugi Sakae, who was quite a renowned anarchocommunist figure at the time. He would become even more famous for his belief in Egoism and his later experimentation in the open relationships mentioned in Chapter III, between himself, Itō, his wife Hōri Yasuko, and Kamichika Ichiko.

Tsuji’s and Itō’s second son, Ryūji, was born August 10th, 1915.[34] At this time she was spending a great deal of time at Seitō headquarters rather than at home, and Tsuji would end up having an affair with Itō’s cousin. Shortly thereafter they ended their relationship, and Itō and Tsuji would keep Ryūji and Makoto respectively after their separation.[35]

Itō shortly thereafter entered into Ōsugi’s fourperson “free love” relationship. Tsuji returned to Asakusa and advertised his services as a teacher of English, shakuhachi flute, and violin. He evidently attracted a number of students, though he became increasingly selfindulgent and alcoholic.[36] Seitō was shut down in 1916. In 1917 it seems Tsuji began wandering about the country as a vagabond, often with his son, playing the shakuhachi for great lengths of time. He would stay overnight in various temples and shrines as well as the houses of friends. A few years later, in 1920, Tsuji learned of and joined the newly blossoming Japanese Dadaist movement through a visit by Takahashi Shinkichi (Chapter III).

A few years later, the Great Kantō Earthquake struck, and in its wake came a rightist political power shift. The authorities, allegedly fearing that anarchists would “take advantage” of the ensuing chaos, began to crack down on radicals. This is less surprising when one considers that the contemporary Japanese government was barely older than Tsuji himself and Japan had already gone through a tremendous amount of censorship and authoritarian law enforcement for the preceding two decades.[37] Thus erupted the Amakasu Incident in which Itō, Ōsugi, and Ōsugi’s six-year-old nephew were massacred by the military policeman Amakasu and his men (Chapter III).

Tsuji was a controversial writer during a period of time at which it was dangerous to write “questionable” literature. People in his social environment (such as Itō, Ōsugi, Kōtoku Shūsui, and Kaneko Fumiko) were subjected to arbitrary arrest, confiscation of materials, and/or murder by the authorities. Because of his ideological and social proximity to these individuals Tsuji became particularly sensitive to the growing oppressiveness of the Japanese government leading up to World War II. For Tsuji to leave the country after the Amakasu Incident is prescient of what would become a norm for controversial writers in 1930s Japan when such people were commonly disappeared.[38]

As such, under the title of “Literary Correspondent” for the Yomiuri Shinbun, Tsuji traveled to Paris in 1924, where he and Makoto would live for a year. Upon returning to Japan he would continue to publish translations and original works, now including works such as Max Stirner’s The Ego and its Own. It was in the postearthquake period that Tsuji would become romantic with Kojima Kiyo, and in 1923 his third son, Akio, was born.[39]

About three years prior, Tsuji had begun involving himself in the spread of the newly born Japanese Dadaist movement and developing an even wider set of social contacts. He would participate in theatre as well as literature and the running of the (probably fictional) Café Dada mentioned in Chapter III. It is from this period surrounding 1923 that Tsuji’s most wellknown works were published, though major book publications incorporated some writings that he had written many years earlier. While this was the heyday of Dada in Japan, times were also fraught with censorship and the cancellation of events. Confiscation of publications resultant from government intervention was a frequent occurrence.

In 1931 Tsuji began to live with lover Matsuo Toshiko[40], and they would continue to be in contact for the rest of Tsuji’s life. Then, in 1932, Tsuji had what is often thought to be a mental breakdown. One night during a party, Tsuji climbed to the second floor and began flapping his arms and crying “I am the birdman!”[41], eventually jumping from the building, running around, and jumping onto the table calling “kyaaaaaa, kyaaaa!!”[42] Tsuji was already quite famous by this time for his writings, lifestyle, and social life, and this event would become a scandal in the newspapers, which bore articles with titles such as “Tsuji Jun Becomes a Tengu”[43].

Whether this event constituted a mental breakdown or if it was merely a wild antic by an eccentric Dadaist is debatable. After all, Takahashi Shinkichi was smeared by the media as having “gone nuts” after having swatted a taxi driver with a cane during an argument, an act which Tsuji defended as an act resulting from merely his Dadaist eccentricity and the heat of the moment.[44]

However, shortly after, Tsuji was institutionalized in a mental hospital, and the doctor there would diagnose him with “temporary psychosis” resultant from habitual drinking. Soon afterwards Tsuji begin roaming again, dressed in the raiment of a wandering Zen monk (complete with sedge hood and shakuhachi)[45] [46], and over the next few years he would repeatedly end up in the hands of the police. As the years went by his associates described him as increasingly out of touch with reality, and he would enter mental institutions several more times. While the tengu incident may not have been an act of lunacy, it seems his mental health in the years to follow broke down in a major way. [47] That Tsuji was first brought to fame by his translation of Lombroso’s book on prodigy madness was, it seems, darkly prescient.

Having left behind his writing career, Tsuji made ends meet by going door to door playing the shakuhachi and by relying on the generosity of his friends and royalties from his old publications. He was also supported by the “Tsuji Jun Fan Club” that was created in 1925 (see Chapter VI: “Reception”).[48] As the years progressed, Tsuji became more and more absorbed with Buddhism, particularly with the Tannishō and Shinran[49]. Ultimately, in 1944, while he was staying in a friend’s one bedroom apartment in Tokyo, Tsuji was found dead from starvation. He is buried at Saifuku Temple in Tokyo.[50]

To Write in an Increasingly Oppressive Climate

Tsuji was a writer in the highly censored and dangerous decades leading up to World War II, and one of radical ideas at that. Having witnessed friends and lovers being imprisoned or murdered for continuing to speak their mind, Tsuji was acutely aware of the implications of being a writer. Having been close to so many anarchists and other dissidents would have made him even more of a target. Whether or not to continue to write would be a question he would perpetually struggle with. In 1924 Tsuji responded to the political climate by leaving the country, yet returnedand while in Japan was inclined to vagabondage. Not only did Tsuji’s wandering suit his philosophy and desired freewheeling lifestyle, it suited his need to evade government surveillance and enforced silencing. That he remained so vocal and successful in making a living as a writer in

such times was indeed an accomplishment.

Tsuji’s feelings about writing in such a political climate are best summed up in a passage from “Vagabond Writings”[51]:

Even if I get up the casual desire to express myself again, such expressions are basically forbidden by the current social system. Basically, in today’s world, at least in the society I’m living in, there really isn’t freedom of speech. When I think of this, I get pretty ill at ease. The passion to go against this and speak anyway just does not come about, so in this way it all begins to bottle up, and I shut up. Even if we’re all humans and we’re feeling this way together, this world’s constraints are tight. These days it seems you really can’t talk this way, and it’s fashionable now to peg things as “dangerous thoughts”. ‘Til now I’ve been swallowing these words dutifully. Naturally, I pity my low intelligence.

After this section Tsuji renounces affiliating with any sort of nationality and submitting to any authority other than himself. He says he wants to rid himself of such duties and cares, to instead live with intentions probably not unlike “the fine thoughts of an insect” (a thoroughly Egoistic and appropriately Dadaist turn of phrase). He then continues that, were he living instead as a peasant in Russia at the time, he would surely be shot to death.[52]

Regardless of his apprehensions, Tsuji continued to write and churned out a great number of translations as well in the years to come. He reacted to the climate of censorship instead with a lifestyle of physical mobility through adopting the transience of a vagabond.

That I, without an objective and completely lightheartedly, walkhaving unawares become absorbed in the winds and water and grass among other things in nature, it is not unusual for my existence to become suspicious. And because my existence is in such a suspicious position, I am flying off from this society and vanishing. In such circumstances there is a possibility of feeling the “vagabond’s religious ecstasy”. At such times one may become utterly lost in their experience. Thus, when I set myself to putting something down on paper, at last feelings from those moments drift into my mind, and I am compelled to make these feelings known.

When I am compelled to write, it is already too late and I become an utterly shackled captive ... Thus, after writing and garrulously chatting I often feel I have surely done something tremendously pointless. This results in me lacking the spirit to write. Nevertheless, thus far and from here on out, I have written, will continue to write.

My impulse to wander comes about from the uneasiness of staying still ... and this uneasiness is for me quite dreadful.[53]

While Tsuji’s restlessness is likely the product of a variety of forces, part of this is surely the result of the suppression his associates had been encountering for decades. This text was written in 1921: two years after Tsuji gave himself up to komusō style wandering, two years before the Amakasu Incident and the martial law resulting from the Great Kantō Earthquake. Thereafter conditions worsened with the ramping up of the war and Tsuji would continue wandering until the final year of his life, 1944.

Personality & Lifestyle[54]

Curiously, Tsuji is described by some as a rather shy, cowardly person lacking in conviction, especially when compared to Ōsugi[55]. Partly, this is probably a depiction resulting from having been around so many activists with high political ideals. Tsuji’s writing is full of selfdeprecating comments typical of a polite Japanese, so he does not come across much as an egotistical person. However, a strongly individualistic attitude and selfrespect permeates his writing and he is insistent on not changing his own behaviour to suit the norms of those around him. He can be very blunt when describing how “lazy” and egoistic he is, but he does not usually portray this as a habit he wants to break. Tsuji’s work generally suggests that he merely has little care for portraying himself in a contrived light and cares little for how he is labelled by others, as we have seen in his comment about “isms”: “Whatever sort of ‘ist’ you call me, for whatever reason, doesn’t really matter to me ... even ‘Dadaist’ ... I am going to be my own variety of Dada regardless”.[56]

In general terms we can understand Tsuji as a Bohemian[57] and an Epicurean. While these themes are further expanded upon in Chapter V, two attributes of these philosophies that he exemplified are those of being primarily interested in the artistic and living in accord with simple, philosophical values (of a rather anticonsumerist bent). Indeed, Tsuji did not choose to become a wealthy individual but would frequently wander the country with little more than a shakuhachi.

Tsuji further suggests these attributes when he describes himself as an individual interested in living simply and freely, indulging in “real art” that uses depictions that get to “the heart of the matter” (i.e. consist of mental and emotional content)[58] rather than of fancy minutiae. He says that, regarding haiku, he has no interest in the names and fine details of various trees and flowers, but wants instead to get to the point.[59] It is probably this that has led him to write proliferously through essays as opposed to volumes of flowery poetry. Through a Bohemian and Epicurean approach as it may have been, Tsuji was enamoured with artistic expressions of the human condition, which provided him a lifelong connection to reading, writing, music, and the arts.

Especially after losing his job at Itō’s school, Tsuji made many friends and associates. From the way Kojima Kiyo and Matsuo Toshiko describe him in their memoirs[60], Tsuji was a loving man, intent on not domineering over his lovers, children, and others. However, he was often an utter drunkard and he was less than enthusiastic about parenting (being at times downright neglectful)he would not let raising a child deter him from what he sought to do.

That Makoto, when he grew older, would be more than a little unwilling to take interviews about his father was probably the result of both this, and the desire to live a somewhat normal life despite being cast in the shadow of his famous, eccentric father. The same is likely true for Mako, daughter of Itō and Ōsugi, who was also not predisposed to speaking with the media about her (in)famous parents.[61]

From “Tsuji Jun and the Teachings of the Unmensch[62]”

For a deeper understanding of Tsuji’s personality, let us take a selection written about Tsuji by Hagiwara Kyōjirō:

This person, “Tsuji Jun”, is the most interesting figure in Japan today. He has taken on elements from a variety of cultures he was exposed to: Tokyo literature, Christianity, Buddhism, English literature, and Nihilism. He is like a comical writer, like a commandment-breaking monk, like Christ, like a man of developed character, like a Dadaist. When he drinks, Tsuji spits out broken jokes and scathing sarcasm without respect ... but when he sobers, he becomes sad, he wanders about the town blowing his shakuhachi. In his music lies the heartbreaking despair and nostalgia represented in the lyricism of his poetry. He plays the shakuhachi, crying alone.

Vagrants and labourers of the town gather about him. The defeated unemployed and the penniless find in him their own home and religion ... his disciples are the hungry and the poor of the world. Surrounded by these disciples he passionately preaches the Good News of Nihilism. But he is not Christlike, and he preaches but drunken nonsense. Then the disciples call him merely “Tsuji” without respect and sometimes hit him on the head. This is a strange religion ...

What the hell is Tsuji Jun? A poet, a literary man, and yetan ordinary guy, a spiritual man ... thinking over human history, he sought his principles and how to live rightly. This in the pattern of Goethe, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Baudelaire, Buddha, and Socrates ...

But unfortunately this was the beginning of his tragedy. A man of his sincerity cannot live well in today’s Japanese culture and literary circle. Why did Arishima Takeo kill himself? Why did Ikuta Shungetsu kill himself? Why do so many sincere poets suffer from persecution? It is tragic that a literary man like Tsuji Jun had to be born in Japan ... Thus, Tsuji chose not to express himself with a pen so much as he chose to express himself through living, as conveyed by his personality. That is, Tsuji himself was his expression’s piece of work.

But here Tsuji has regrettably been portrayed as a religious character. It sounds contradictory, but Tsuji is a religious man without a religion. Although he speaks of Egoism alongside Max Stirner, he is by the side of [the Buddhist monk] Shinran ... teaching of being a beggar with Buddha,, teaching the life of a drunkard like Verlaine [the French poet] ... his spirit cannot stay in one place ...

As art is not a religion, neither is Tsuji’s life religious. But in a sense it is. Tsuji calls himself an Unmensch ... If Nietzsche’s Zarathustra is religious ... then Tsuji’s teaching would be a better religion than Nietzsche’s, for Tsuji lives in accord with his principles as himself ...

Tsuji is a sacrifice of modern culture ... In the Japanese literary world Tsuji can be considered a rebel. But this is not because he is a drunkard, nor because he lacks manners, nor because he is an anarchist. It is because he puts forth his dirty ironies as boldly as a bandit ... Tsuji himself is very shy and timid in person ... but his clarity and selfrespect exposes the falsities of the famous in the literary world ... [though] to many he really comes across as an anarchistic rogue ...

The literary world only sees him as having been born in this world to provide a source for gossip, but he is like Chaplin producing seeds of humour in their rumours ... The common Japanese literati do not understand that the laugh of Chaplin is a contradictory tragedy ... In a society of base, closedminded people idealists are always taken as madmen or clowns.

Tsuji Jun is always drunk. If he doesn’t drink he can’t stand the suffering and sorrow of life. On the rare occasion he is sober ... he does look the part of an incompetent and Unmenschian fool. Then his faithful disciples bring him saké in place of a ceremonial offering, pour electricity back into his robot heart, and wait for him to start moving ... In this way the teaching of the Unmensch begins. It is a religion for the weak, the proletariat, the egoists, and those of broken personalities, and at the same timeit is a most pure, a most sorrowful religion for modern intellectuals.[63]

III. Background & Context

An Overview of PreWar Japanese Anarchism

Tsuji was deeply interested in socialism and believed in an “Anarchist Utopia” for a period of time, but reached such a point of scepticism that he would only consider himself a Stirnerist and Nihilist, and years later he would shuck even the title “Dadaist” because he found it overly burdensome[64]. While it is true that Stirner did not describe himself as an Anarchist, the philosophy both Tsuji and Stirner advocated is patently anarchistic enough that the term still can still apply to them, even after Tsuji’s disenchantment with socialist Anarchism. A history of Japanese Anarchism is furthermore vital to this work because Tsuji’s life and social environment, as well as his thought, were deeply embedded in that history extending from the beginnings of the movement to what would mark the end of its prewar period.

Anarchism was first popularized in Japan by Kōtoku Shūsui[65] at the beginning of the 1900s. Kōtoku was a fervent socialist since before the turn of the century and was a highly active freelance journalist and publisher. He is famous for heading the Heimin Shimbun (Commoner’s Newspaper) and for speaking out against the RussoJapanese War of 1905, at which point Kōtoku was imprisoned for violating press censorship laws. Kōtoku was the principle voice of the socialist antiwar movement and while the loss of his presence during imprisonment made a strong impact at the time, Kōtoku would emerge five months later an anarchist, having read Kropotkin’s Factories, Fields, and Workshops while imprisoned[66].

After this point Kōtoku began speaking out against the Japanese emperor system and other authorities, but shortly departed for the United States, presumably to evade being censored again. There he made friends among the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) and other radical groups. Overseas he became even further radicalized. After witnessing what he saw as mutual aid in direct action in the wake of the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, Kōtoku became even more confident in espousing direct action as the most effective means of creating social change[67].

It was repeatedly only random chance that saved the perpetuation of the anarchist movement in Japan. Kōtoku was out of Tokyo when the Red Flag Incident occurred in 1908, wherein a group of radicals including Ōsugi Sakae were arrested for having displayed banners and having called out anarchist slogans at a friend’s release from prison[68]. While this saved Kōtoku from imprisonment at the time, he was to be arrested again in 1910 and shortly thereafter executed in the High Treason Incident. The fact that Ōsugi was still in jail at the time of the High Treason Incident again allowed the anarchist movement to retain one of its key figures, at least until Ōsugi’s murder twelve years later.

The High Treason Incident of 1910 was the trial of a group of socialists and anarchists who were allegedly plotting to assassinate the Japanese emperor, during which dozens of individuals were subject to mass arrest. Whilst the evidence for Kōtoku’s alleged intentions is scant, his position as a major leader in the socialist and anarchist movements made him a sure target for the roundup. Several scholars have remarked upon the case’s lack of due process and the shakiness of evidence, some going as far as calling it a show trial[69].

Kōtoku and his former wife, anarcho-feminist Kanno Suga, as well as twenty-two others (including several monks such as Gudō Uchiyama) were sentenced to death by hanging. Eleven of these twentyfour later had their sentences commuted to life imprisonment. Nonetheless, the rushed and secretive trial process as well as its iconically forceful suppression of free thought drew criticism from various individuals including the wellrespected author Mori Ōgai[70]. The High Treason Incident resulted in the renunciation (tenkō 転向) of some socialists as well as the radicalization of others. This resulted in what was known as the first winter of socialism/anarchism in Japan[71].

From this point on Ōsugi would continue publishing Heimin Shimbun in Kōtoku’s absence. Ōsugi’s energetic efforts led him to be known as anarchism’s most respected figure, and it could be said that he built up the foundations for the following “spring” of anarchism. As time went by the variety of strains of anarchism widened to incorporate more ideas about free love, syndicalism, and Stirnerism/Nihilism. This widening would put additional strain on tensions between syndicalist and communist anarchists, resulting in the anarchistbolshevist split of 1921[72]. This period also saw this incorporation of Dadaism into some strands of anarchist thought, as was the case for Tsuji, Mavo, and writers of Aka to Kuro (Red and Black).

Following the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923, the devastation wreaked on the center of Japanese modernity and industry, Tokyo, created immense disorder and strife. The chaos that followed put many in the government in a state of panic, which would manifest in the assassinations and imprisonments of several political radicals, most notably including those who became martyrs in the Amakasu incident and Kaneko Fumiko. The Amakasu Incident involved the abduction of Ōsugi Sakae, his anarcho-feminist lover Itō Noe, and their six-year-old nephew, all of whom would later be beaten to death by a squad of military police led by Lieutenant Amakasu Masahiko. Afterwards their bodies were thrown down a well. The crackdown on political radicals and their publications that would happen around this event would amount to a second “winter” in anarchism and socialism in Japan[73].

This crackdown and the shock resulting from the devastation of modernity’s centre would result in fervent NeoDada/Anarchist art. This phenomenon has been compared to the shock of World War I that stoked Dadaism in Europe. The quake also resulted in immense personal impact on Tsuji, as with many people across Japan[74]. From this point on until the end of World War II, censorship and political intolerance would rise to the point of extinguishing the potential for a sizeable anarchist movement, though for about five years after the quake there was a lot of radical (including anarchist) political activity.

Tsuji had been a subscriber to Kōtoku’s Heimin Shimbun since the age of twenty[75] and he associated with many key figures of Japanese anarchism over the course of his life, reading various foreign language anarchist texts. It was particularly from after the High Treason Incident into the 1920s during which Tsuji became increasingly sceptical of the plausibility of revolution[76].

Stirner, whom Tsuji so greatly admired, looked disfavourably on communism and considered it another form of authority suppressing the will of the individual: “loudly as it always attacks the ‘State’, what it intends is itself again a State”[77]. However, this is not to say that Tsuji was not very familiar and sympathetic to the popular branches of communist anarchism and anarchosyndicalismindeed, Stirner also cuts his criticisms of communism with a bit of sympathy[78]. However unlike his contemporary Egoist, Ōsugi, Tsuji would not devote a lot of energy to expounding ideas of social justice in tandem with ideas about radical individualism (Stirnerism).

On Nihilism in Japan

The Nihilisms of Stirner and Nietzsche were very influential to Tsuji and such contemporaries as Murayama Tomoyoshi[79], Ōsugi Sakae[80], and Kaneko Fumiko[81] as well as to other notable figures of the time such as the naturalist writer Masamune Hakuchō.

Egoism as a Form of Nihilism

While it is debated as to whether or not there was a direct stream of influence between Nietzsche and Stirner’s work[82], commonalities between Stirner’s Egoism and Nietzschean Nihilism have been recognized by numerous scholars. Whilst there are profound differences between Nietzsche’s and Stirner’s philosophies and the different contexts from which their ideas arose remain important, some would have Stirner’s Egoism fall under the category of Nihilism rather than strictly binding the term “Nihilism” to the philosophies of Nietzsche and Dostoevsky only.

For example, in the chapter “Nihilism as Egoism: Max Stirner” in Nihirizumu[83], Nishitani presents Stirner’s Egoism as a form of Nihilism for, among other things, the fact that it is 1) opposed to the idealism and progressive conception of history common among Stirner’s contemporaries, 2) based on the negation of the absolutes imposed by religiosity, and 3) embraces “nothing” as the basis for existence[84]. The present work will regard Tsuji’s and Stirner’s Egoism as a form of Nihilism because of these foundational commonalities.[85] This is noteworthy because of Tsuji’s use of both the terms “nihilism” and “egoism” widely to support ideas that could be identified as either by this rubric.

Relation to Darwinism

This work regards activities that took place mostly in the 1910s, ‘20s, and ‘30s, and Darwinism and Social Darwinism were both deeply influential to many thinkers at the time. Darwin’s The Origin of Species helped excite the atmosphere of questioning human society and how it ought to be run, feeding into the Anarchist, Socialist, Nihilist, literary, and artistic (especially Dadaist) movements. For poet and novelist Shimazaki Tōson this meant “We should leave behind the sweetness of life shown by the romantics and the hedonists. We should make a renewed attempt to dissect human nature scientifically with the knowledge of Darwin’s Origin of Species or Lombroso’s study of criminal psychology”[86] [87]. This demonstrates how Darwin’s ideas fed into Naturalist writing--but it also provided the fertile ground across the board for those various movements that were inspired to question human society.

Social Darwinism, especially as interpreted by Herbert Spencer with his notion of “survival of the fittest”, was influential to the Nihilist Kaneko Fumiko in that it supported her Nihilism’s perception of life being comprised, ultimately, of humans struggling against one another. However, Kaneko did not absorb Spencer’s notion of social evolutionary progress[88] nor, it would seem, the conception of racial superiority[89].

Similarly, anarchocommunists were generally against such concepts, as well as against embracing “survival of the fittest” as a social model. That is, their central principle was that of mutual aid and solidarity rather than competition. However, a strand of Social Darwinist rhetoric was present among the more Marxist individuals among them. This was a result of the presence of Social Darwinism in Marxist literature itself.[90]

This Social Darwinism in Marx essentially criticized the competitive struggle it portrayed as inherent in Capitalism. To quote Engels, “between single capitalists as between whole industries, and whole countries ... is the Darwinian struggle for individual existence, transferred from Nature to society with intensified fury”.[91] Thus, Social Darwinist rhetoric was used in some Japanese anarchist and socialist writing, but it was used in a negative sense in regards to capitalism in order to bolster their argument for a more cooperative rationalist society. Leftist Dadaists, such as Hagiwara and others in Mavo, were as a result caught between their political idealism and their Dadaist desire to smash blind allegiance to social norms, particularly rationalism (Chapter IV). Tsuji and Kaneko, on the other hand, did not bear this conflict as much and left behind political idealism for the quest to free themselves as individuals through Egoism.

Additionally, the bleaker outlook of the individualist anarchism of Tsuji and Kaneko was more in line with the pessimism of Spencer’s Darwinism because they found the struggle of the individual more realistic than revolutionarily overcoming institutions imposing social struggle (especially across classes). However, this outlook resulting from Darwinism did not permeate their Egoist philosophies to the extent that it necessitated those feelings of racial superiority or eugenic ideals popularly associated with Social Darwinism today, much like the anarchists above. Rather, these concepts would have reeked of the justifications used in Japanese imperial expansion, which Tsuji and Kaneko surely encountered from the late 1800s leading up to World War II. This effect is especially a result of having been exposed to the writing of antiimperialist writers they sympathized with, such as Kōtoku. Kaneko would have been especially sensitive to colonialist strains of Social Darwinism, having experienced the Korean annexation

firsthand.

Thus far in my reading of Tsuji’s immense body of work I have yet to find reference to Darwin explicitly, outside of his appearance in Tsuji’s translation of The Man of Genius (one section of which describes Darwin’s idiosyncrasies as possible symptoms of Lombroso’s archetypal genius)[92]. Even were it not for this translation, however, it is a historical inevitability that Tsuji would have been familiar with Darwin’s ideas and would have been influenced by the climate of heated sociopolitical debate that had been stoked by the introduction of Darwinism.

Even if Tsuji had never read Darwin firsthand, there would have been a significant current of influence on Tsuji also through the work of Nietzsche (who was “aroused from his dogmatic slumber by Darwin”[93]). The fact is, Nietzsche was a very popular read amongst people in Tsuji’s social circle as well as an important author for Tsuji himself. Still, it must be remembered that Tsuji’s Nihilism, however impacted by Nietzsche, was more founded on the work of Stirner, whose death predated the publication of Origin.

Darwin’s Origin is of more relevance to the present work than for simple influence, however. It brought up a deeply distressing problem in regards to morality. First let us assume the validity of the Theory of Evolution, as Nietzsche asserted:

Formerly one sought the feeling of grandeur of man by pointing to his divine origin: this has now become a forbidden way, for at its portal stands the ape, together with other gruesome beasts, grinning knowingly as if to say: no further in this direction![94]

Now, to understand Evolution (rather than God) to have created humanity as above, leads to the dilemma of a sudden absence of divine decree necessitating moral behavior. With Nihilism’s assertion that nothing is inherently good or bad, humans would be left in the position to figure out a morality for themselves, if they were to choose to take up morality at all.

Nietzsche does not stop there, however. He then implies that this situation is to be overcome, and that “as long as anyone desires life as he desires happiness he has not yet raised his eyes above the horizon of the animal ... but that is what we all do for the greater part of our lives: we usually fail to emerge out of animality”[95]. From there we are presented with the figure of the Übermensch in furthering his assertion that humanity must raise itself up. Thus we can interpret Nietzsche’s allegory of the camel that became a lion that became a child: one who realizes the emptiness of existence can break themselves free from their burdens by becoming a lion, which is yet an animal, which must then transform into a child in order to acquire the capabilities of imagining a new world, therein overcoming humanity’s condition of animality, which would persist regardless of one’s grasp of Nihilism according to Nietzsche.[96]

Max Stirner, not living long enough to read Origin, did not create Egoism as a response to Darwinism. However, it has been interpreted as an alternative Nihilist answer to this question of morality. While its reply may be a more frightening one, it presented an attractive option for those who were not willing to buy into the necessity for overcoming “the animal condition”.

Stirnerism in a Nutshell[97]

Born in 1806 as Johann Caspar Schmidt in Bayreuth, Germany, Max Stirner took for a pen name his childhood moniker “Stirner” (which it is said he acquired for having a high brow, or stirn in German). Stirnerism was the origin of what is now called Egoist Anarchism, which is one branch of Individualist Anarchism. His philosophy became known through his book The Ego and its Own, published in 1844. The book’s influence has reached far beyond the limits of anarchism and into various branches of philosophy including nihilism and existentialism, drawing comment from figures such as Marx, Feuerbach, and others including such Dadaists as Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp. Just so, Stirner was of great significance to the Dadaist movement in Europe.[98]

The philosophy expounded in Ego presents humankind along the trajectory of (a somewhat inaccurately portrayed, outdated, and at times racist) history as having been plagued by a number of institutions that have stripped people of freedom. These institutions comprised of religious, political, as well as social (societal) examples.[99]

Like Nietzsche, Stirner asserts there are no inherent meanings, essences to anything in the universe, and as a result humankind is but a product of its deterministic history. However, one can understand Stirner as a compatiblist who conceives of the ability of free will (the ego) to exist despite the deterministic outcome of any event. This is not to confuse free will with the necessary existence of a soul, which Stirner denies, along with other religious concepts. Rather, Stirner vehemently opposes any inherent essence, proposing instead that people and their Egos consist of the “creative nothing”.[100] That is to say, much like the concept of mu/kū described in the introduction, “creative nothing” implies that things exist in a state of limitless fluctuation and, because of their ability to change into new things, are creative. However, Stirner phrases this as an ability of creators (who presumably require an Ego in order to willfully create). As Stirner wrote, “I am not nothing in the sense of emptiness, but I am the creative nothing, the nothing out of which I myself as creator create”.[101]

Stirner suggests that in the absence of any inherently necessary purpose in existing and the inevitability for circumstances to change people’s lives (deterministically speaking ), people must come to an understanding of themselves more realistically as common mortals not bound by divine injunction. That is, they must understand themselves as an “underhuman” (Unmensch or teijin 低人). Stirner describes the Unmensch as someone who does not correspond to the popular concept of what it means to be human. That is, they are Egoists that understand themselves to be individuals like “me” and “you” rather than as an example of a prescriptively determined archetypal person[102]. Stirner’s Unmensch[103] comes in sharp contrast with Nietzsche’s Übermensch (“overhuman”) who is a figure put on a pedestal as something that humankind must achieve.

With Stirner’s Unmensch Egoist we see his advocacy of the selfmade individual, the independent thinkerthose who live limited to only what they are deterministically limited to and what they choose to limit themselves with. Thus Stirnerism does not preclude typical moral behaviour, but would argue that the Egoist figures out what (if any ) morals they think they ought to follow, even if they do not coincide with conventional moral standards. Therefore, an Egoist may technically try to achieve some Übermensch ideal so long as they are doing it for themselves. However, Egoism is more commonly thought to imply that one would best understand their inevitable condition as an Unmensch (nondivine figure) and work to free themselves from dictates imposed on them by others.

Indeed, Stirner’s philosophy is a dangerous one because it asks the reader to question such foundational qualities of themselves as morality while at the same time speaking highly of individual freedom. Stirner’s ideas would prove influential to proponents of Illegalism across Europe, especially in France where it spawned groups such as the Bonnot Gang. These groups consisted of individualist anarchists who openly embraced criminal ways of life. However, Stirner makes no apology for publishing such a dangerous philosophy and makes no claim that he did it for the benefit of others[104]. Perhaps this is part of why Takahashi conceived of a “great gulf” between Buddhism and Egoism[105]--being an Egoist does not necessitate being compassionate.

This said, it would seem that Tsuji did not manage to become a criminal or alienate other people entirely by taking up Stirner’s radical philosophy. Even Takahashi admired some aspects of Tsuji, calling him a “pure soul” whose life was “a rebellion against the common run of people and evil”[106]. Rather, the Epicurean side of Tsuji’s philosophy seems to have balanced out whatever frightful behavior might otherwise have been spawned from Stirner’s writing.

While he was often thought of as something of a deadbeat by others[107], Tsuji was not an unproductive individual (as demonstrated by Appendix I) and in fact kept a great many friends and lovers. However, he was prone to foist his parental duties on his mother and would not seek out undesirable forms of employment once embracing Egoism, preferring to rely on writing as a source of income despite those years of poverty this subjected him and his family to. However, to an Egoist, dependants are only dependant because they allow themselves to be so.

On Dada in Japan

Some background reading on the history of Dadaism in Europe is recommended to complement this work[108] because there is insufficient space to discuss this context or the complexities of Dada as an artform and as a philosophy in general.

Dada in Japan is commonly considered to have come about in two waves, the first beginning in the early 1920s as something of an importation from Europe. The second wave is referred to as “NeoDada”, and while some such as Omuka use the term to refer to the resurgence taking place after the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake[109], Kuenzli uses the term to describe the postwar resurgence of Dada in Japan, as led by the Gutai and Hi Red Corner groups in the 1950s[110]. The present work only focuses on the prewar period and therefore would make the most out of using the Great Kantō Earthquake as the dividing line. Tsuji participated from the very inception of Dada in Japan (1920) to its fading away in the years leading up to World War II (early to mid1930s).

By the 1920s modernism had already been considerably reshaping the Japanese art scene, and Dada gradually became ingrained into the greater context of the Taishō period modern art movement (Taishōki Shinkō Bijutsu Undō). As a result of the common context and mutual influence between Dada and other movements in modern Japanese art and literature such as surrealism and futurism, Dada is not easily divided from other currents in avantgarde Japanese art of the same period. Despite this fuzzy line, however, Dada is most pronounced in a few notable individuals who will be covered further in the Contemporaries section.

Originally Dada was limited to the literary world following its introduction in a pair of articles in the Yorozu Chōhō newspaper. The first of these, dating from June 27th 1920, featured works by Kurt Schwitter and Max Pechstein. It was titled “A Strange Phenomenon in the Art Circle of Germany” and included the first written usage of the term “Dadaist” in Japan[111].

The more relevant second article, from August 5th of the same year, featured Marius de Zayas and consisted of two parts, one being titled “The Latest Art of Epicureanism” by Wakatsuki Shiran, and the second titled “A View of Dada” by Yōtōsei. In Wakatsuki’s article the term “Dada” is defined as being the same as the Japanese mu and claimed Dadaists were “radical, epicurean, egoist, extreme individualists, anarchist, and realist, [and] their art ... lack[ed] principles” as a result of the social situation resulting from World War I [112].

An onslaught of other articles would continue to pop up as Dada became a more and more popular topic from 1921 on[113], at which point Tsuji and Takahashi also were becoming seriously involved in the creation of Dadaist literature. Shortly thereafter Mavo, Yoshiyuki, and Red and Black began producing their major contributions as well.

Dada survived in Japan into the 1930s, at which point a wide variety of factors led to its fading away, most prominently including the increasing censorship and economic hardship resultant of the Great Kantō Earthquake and Japan’s increasing imperialism and nationalist militarization.

While Tsuji Jun has called himself the first Dadaist of Japan and is often called the prime (if not the first) establisher of literary Dadaism in Japan, Takahashi Shinkichi could also be considered for that title and has also called himself the first Japanese Dadaist[114]. Tsuji was originally introduced to Dada through Takahashi by means of the August 15th article, and it could be said that their interests took root at basically the same time.

Relation to Ero Guro Nansensu

The term ero guro nansensu (or ero guro for short) is a general term used to express tendencies of deviant art and literature that explored the extremes of erotic, grotesque, and/or nonsensical themes, especially in 1920s and 1930s Japan, but the term also applies to some postwar works. Perhaps the most wellknown ero guro writers were Edogawa Ranpo and Yumeno Kyūsaku.

Because it is a term meant to suit a general thematic trend, it does not map neatly onto the Japanese Dadaist movements, as authors and artists varied in their usage of each of these themes. In fact, ero guro is more closely associated with mobo (“modern boy”) popular magazines than the more esoteric stream of Dadaism. However, it is no coincidence that the heyday of this phenomenon coincided with the pinnacle of prewar Japanese Dadaism. That is, the conditions that were foundational to the rise of Dadaism were also foundational to the more strictly surrealist varieties of art and literature, as well as to ero guro. Also, these movements did not exist in a vacuum and did meld with each other, making classifying avantgarde writers and artists of this period difficult.

Dada, however, does have a particularly good amount in common with the nonsensical portion of ero guro nansensu. That is, to break away from adherence to the modern Japanese convention of rationalism, some nonsensical elements were used in Dada. Also, since the emphasis of Dada was more on liberation than it was for pleasing the viewer of Dada, Dadaists were less prone to make compromises in their creation process for the sake of popular intelligibility. Erotic and grotesque content, of course, also lent avenues to Japanese Dadaists to break from convention[115].

Contemporaries of Tsuji Jun

Mavo

Mavo was a group of Dadaists active primarily in the 1920s, spearheaded by Murayama Tomoyoshi. Hagiwara Kyōjirō (from later in this section) would join the group later in its history and represented one part of a core of fervent anarchists who participated in the group’s activities. Even the famed feminist writer Hayashi Fumiko[116] was a contributor to Mavo’s eponymous publication. Both Murayama and Hagiwara were fairly close associates of Tsuji, who also contributed to the Mavo publication.[117]

Murayama travelled to Berlin where he became enamoured of Dadaism, returning to Tokyo in 1923 whereupon he would take that inspiration and become the leading figure of Mavo, further radicalizing the group[118]. Mavo engaged in multiple artforms including theatre, construction, painting, typesetting, poetry, photography, architecture, and dance. This group was essential in making Dada a recognizable movement in Japan and would contribute heavily to the Japanese modern art scene. Mavo is of particular importance in this work because of its bridging of anarchist theory and Dadaism[119].

As was the case for Tsuji (Chapter V), Mavo was involved in creating through art a new and freer lifestyle and worldview for themselves[120]. However, Mavo was much more involved in sending socialist anarchist messages through this than Tsuji, who focused primarily on ideas of individualist anarchism[121].

Yoshiyuki Eisuke

Yoshiyuki Eisuke (19061940) was a Dadaist, poet, and novelist writing in the 1920s and 1930s, contributing to various publications including the Dadaizumu magazine and Kyomushisō (Nihilism, to which Murayama and Hagiwara also contributed). Today he is mostly known for being the father of the famed writer Yoshiyuki Junnosuke. He wrote much about the darker side of Japanese city life (e.g. prostitution, political corruption, industrial working conditions) and grew increasingly critical of capitalism as a result[122].

The works of Tsuji and Takahashi were highly influential to Yoshiyuki[123], though Yoshiyuki can be considered much more closely aligned with the Proletarian Writers than Tsuji or Takahashi. The three worked together on publications and conferences, and Yoshiyuki’s magazine ran ads for the Café Dada discussed later in this chapter.[124]

Hagiwara Kyōjirō

Hagiwara was a fervent anarchist and Dadaist poet. His writing is perhaps the most explosive of any author mentioned here, and he stands as an icon of the passion and extremity that characterized the NeoDada that emerged from the desolation of the Great Kantō Earthquake. Before joining Mavo, Hagiwara was a principal writer in the anarchist avantgarde poetry magazine Red and Black. While Red and Black did not openly call itself Dadaist, the similarities are strong enough that various scholars consider them to be a part of the Dadaist movement anyway. Hagiwara also performed in the anarchist theatre troupe Kaihōza and performed modern dance under the name Fujimura Yukio[125].

Hagiwara was a close friend of Tsuji’s and together frequented the Café Lebanon, along with many other anarchists and radicals, such as Hayashi Fumiko, Ōsugi Sakae, Ishikawa Sanshirō, Takahashi Shinkichi, and Hirabayashi Taiko. This café would serve as a den where radicals could meet each other, share their work, and stoke their ideas with conversation. Going to the theatre and participating in thespian performance also served this purpose, and both Tsuji and Hagiwara engaged in this.

If we are to understand the advertisements for it as nonfictional, various Dadaists were involved in running “Café Dada” and its (never performed) theatrical performances. According to advertisements in Yoshiyuki’s magazine Baichi Shūsui (Selling Shame and Ugly Text), Tsuji was scripted to play shakuhachi there in accompaniment to his mother’s shamisen, Murayama’s dancing, and chanting by Takahashi.[126] This café was advertised as located in Kamata, Tokyo and resembled Hugo Ball’s (18861927) Cabaret Voltaire café in Zurich[127].

Also, Café Lebanon hosted art and poetry exhibitions (including the work of Red and Black), further giving voice to its visitors. Just so, the artistic and political hotbed cafés in part represented the heights of modern cosmopolitan culture in Tokyo, and were crucial to various avantgarde movements in Japan. This did not go unnoticed by the authorities, of course, who confiscated some of the poetry posted there on charges of “corruption of public morals” and “disruption of public stability and order”.[128] The authorities would also frequently cancel theatre performances and other events (an occurrence Omuka terms “misfires”). That there was so much interaction going on between the various proponents of avantgarde art, literature, and politics, both in and out of cafés and theatres, demonstrates the necessity of understanding Tsuji’s social environment in the process of understanding his own story.

Takahashi Shinkichi

Takahashi Shinkichi (19011987) and Tsuji together were the first and most influential prewar Dadaist writers in Japan. Takahashi came to know of Dada in 1921 through the two articles mentioned in the Dada overview earlier in this chapter, which he introduced to Tsuji when they first met. During this visit, Takahashi allegedly came wanting a copy of Tsuji’s full translation of Ego, and Stirner would continue to prove influential on Takahashi, despite the criticisms he would address to Egoism and Tsuji later on.[129] Since both authors began writing Dada at roughly the same time, it becomes difficult to discern whether the Buddhist influence on Tsuji’s work came largely from his friendship with Takahashi or from elsewhere.

Like Tsuji, Takahashi was not overly enamoured of revolutionary socialist and anarchist politics, feeling more sympathy with Stirner’s brand of nihilistic anarchism. Takahashi had joined a monastery in 1921 but began to have his doubts about the esoteric Buddhist rules and practices there, “leading him deliberately to act out the transgression of commandments”.[130] Takahashi was then expelled from the temple. That Takahashi behaved in this way and then further immersed himself in (a quasiBuddhist) Dada demonstrates his sentiment that Buddhist nothingness does not necessitate the following of such strict (and perhaps seemingly arbitrary) rules and practices as those he experienced at the monastery. Takahashi’s career as a Dadaist poet would prove to be a relatively short one, however, after which he devoted himself to a more strictly Zen poetry. The convergence of Buddhism and Dada in Takahashi’s mind is of relevance to the present work because of its similarity to that convergence which took place in Tsuji’s.

Kaneko Fumiko

While the preceding four selections above describe Dadaists contemporary with Tsuji, Kaneko was not a Dadaist but an Anarchist, Nihilist, Egoist, and poet. It is likely that she was introduced to Stirner’s ideas through Tsuji’s translation of The ego and its own, which had been published a few years before her remarks about Stirnerism began to appear.[131] After her mother failed to sell her to a brothel, Kaneko was sent to overseas at the age of nine, where she experienced the poverty and oppression in Korea, which had been annexed by Japan. Both this and her abandonment by her parents were surely influential to the development of her Nihilist, Anarchist philosophy. Also influential to this was her acquaintance with Pak Yeol, a Korean anarchist, with whom she would form the twoperson anarchist group “Society of Malcontents” and later marry on the verge of their imprisonment.[132]

While Kaneko was farther removed from Tsuji’s social circle than those closeknit individuals mentioned elsewhere in this section, her thoroughly Egoist philosophy makes her thought the most closely akin to Tsuji’s. While Kaneko was somewhat involved in the politics of Korean independence, she was not as driven to activism as were others like Pak. What written contributions she made to Japanese Anarchist and Nihilist thought were more bound to her own Egoism:

‘I am not living for the sake of other people. Must I not earn my own true satisfaction and freedom? ... Even though neither of us [Kaneko or nihilist Niiyama Hatsuyo] had ideals regarding society, we both thought about having something we could call our own true task. It wasn’t that we felt it had to be fulfilled. We merely thought it would be enough if we could look upon it as our true task.’[133]