Various Authors

Dumpster Diving the Anarchist Library Text Bin – Part One

A library enthusiasts introduction

The Why, The How & The Lessons Learned

A Short List of Some of the Deleted Texts

2. Thirty Years Ago Today I Shot My First Fascist

4. Child Molestation vs. Child Love (Critically Annotated)

Introduction: A Word of Warning

Child Molestation vs. Child Love (Main text from 1987)

Critical Annotations by Black Oak Clique

Chapter 1: The Early Composition of Fascist Individualism

Chapter 2: The Creation of the Post-Left

6. Where did all the tankies come from?

8. Armenia doesn’t need another political party — it needs a MOVEMENT!

9. The Evolution of the Language Faculty

1.1. Clarifying the FLB/FLN distinction

1.2. Biolinguistics and the Minimalist Program

2. What’s special: a reexamination of the evidence

2.2.1. “Speech is special” as a default hypothesis

2.2.2. Comparative studies of animal speech perception

2.2.3. Neural data on speech perception

2.3.1. Complex vocal imitation

2.7. Summary: our view of the evidence

3. Conclusion: where do we go from here?

10. International Council Correspondence, Volume 1, Issue 1

The Future of the German Labor Movement

Unity for What?:Communist League and the American Workers Party Move to Form New Party

11. Chinese Anarchism for the 21th Century

Part 1: Three Principles of the People (三民主義, Sān Mín Zhǔ Yì)

Nationalism (民族主義, Mín Zú Zhǔ Yì)

Democracy (民權主義, Mín Quán Zhǔ Yì)

People’s Livelihood (民生主義, Mín Shēng Zhǔ Yì)

Part 2: Working with Other Ethnic Groups

12. Does the Unabomber have any relevance to anarchism?

1953 — Ted becomes a primitivist

1971 — Ted misreads the minimalist anarchist Jaques Ellul

1979 — Ted writes to Wild America

1985 — The Unabomber’s First Public Primitivist Argument

1990 — Earth First! shifts with the times

1992 — The Earth Liberation Front emerges

1995 — The Manifesto is Published

Other anarchists critiques his message

1996 — Ted begins corresponding with various anarchists post-arrest

1998 — Ted has the same message post-arrest

2001 — An ELF cell debates similarly violent acts against people for the wild

2003 — A similarly violent insurrectionary network emerges with many anticiv cells

2006 — Ted publicly breaks with anarchism

2010 — Similar insurrectionary violence emerges in Mexico in a big way

Individualists Tending to the Wild emerges

Kaczynski’s influence specifically

Other anarchist actions inspired partially by Kaczynski

2012 — Various eco-anarchist actions reference Ted K as a source of inspiration

Logging corporation sabotaged in solidarity with Ted K

Greek anarchist anti-tech cell quotes Ted K

An anticiv cell in Russia calling itself ELF share their support for FAI & ITS

2013 — Electrical substation attacked

Ted’s book ‘Anti-Tech Revolution’ is published

Cars burnt under the umbrella of ELF/FAI

2019 — Ted disavows any identification as an anarchist

13. Disrupting The Purist Anarchist Pipeline

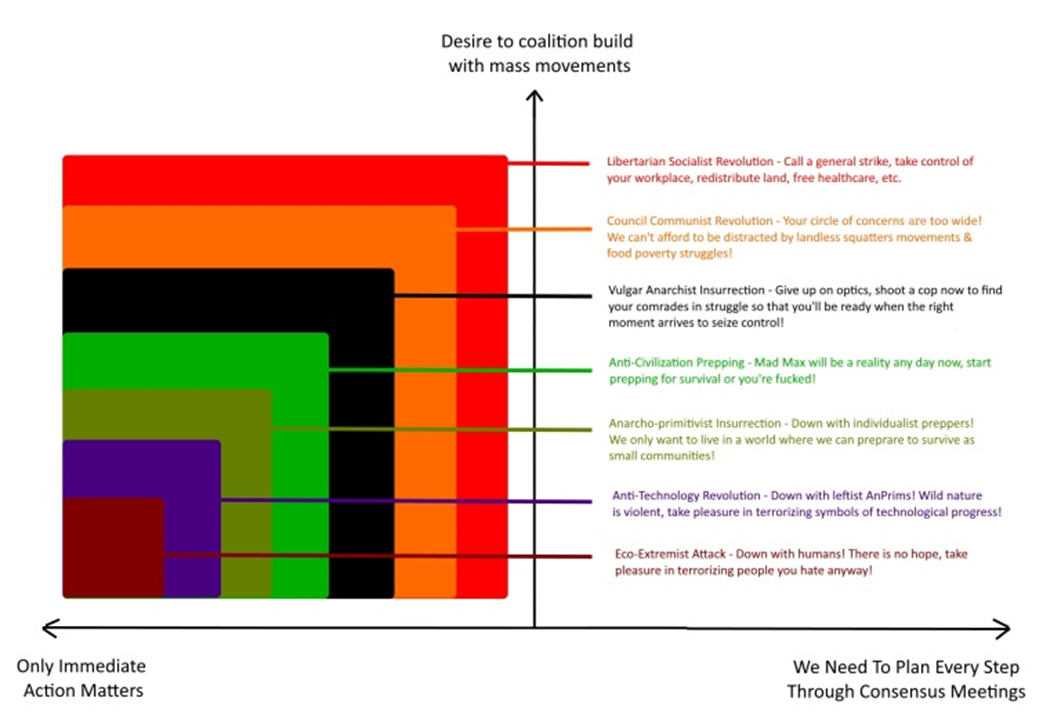

An analogy by way of a diagram

The expanded limits of violence

Insurrectionary Anarchism as Primary

The expanded limits of violence

The expanded limits of violence

The expanded limits of violence

Eco-Extremist Nature Worshipers

The expanded limits of violence

The expanded limits of violence

A broad approach with specialized interests

14. Communization and the abolition of gender

I. The Construction of the Category ‘Woman’

II. The Destruction of the Category ‘Woman’ Though

15. Guerilla Open Access Manifesto

17. ‘Human Rights’ and the Discontinuous Mind

18. Chile: Anatomy of an economic miracle, 1970–1986

Anatomy of an Economic Miracle

19. Ableism at the Anarchy Fair

20. Think for Yourself, Question Authority

2. The Politics of Ecstasy/The Seven Levels of Consciousness (the 60s)

2.1. Ancient models are good but not enough

2.2. “The Seven Tongues of God”

2.3. Leary’s model of the Seven Levels of Consciousness

2. Emotional Stupor (level 6):

3. The State of Ego Consciousness/The Mental-social-symbolic Level (level 5):

4. The Sensory Level (level 4):

5. The Somatic (Body) Level (level 3):

6. The Cellular Level (level 2):

7. The Atomic — Solar Level (level 1):

2.4. The importance of “set” and “setting”

2.5. The political and ethical aspects of Leary’s “Politics of Ecstasy”

2.6. Leary’s impact on the young generation of the 60s

2.6.1. “ACID IS NOT FOR EVERYBODY”

3.1. S.M.I.²L.E. to fuse with the Higher Intelligence

3.2. Imprinting and conditioning

3.3. The Eight Circuits of Consciousness

1. The Bio-Survival Circuit (trust/distrust):

2. The Emotional-Territorial Circuit (assertiveness/submissiveness):

3. The Dexterity-Symbolism Circuit (cleverness/clumsiness):

6. The Neuroelectric-Metaprogramming Circuit:

3.4. Neuropolitics: Representative government replaced by an “electronic nervous system”

3.5. Better living through technology/The impact of Leary’s Exo-Psychology theory

4. Chaos & Cyberculture (the 80s and 90s)

4.1.1. The Philosophy of Chaos

4.1.2. Quantum physics and the “user-friendly” Quantum universe

4.1.3. The info-starved “tri-brain amphibian”

4.2. Countercultures (the Beat Generation, the hippies, the cyberpunks/the New Breed)

4.2.2. The organizational principles of the “cyber-society”

4.3. The observer-created universe

4.5. Designer Dying/The postbiological options of the Information Species

4.6. A comparison/summary of Leary’s theories

4.7. A critical analysis of the cyberdelic counterculture of the 90s

4.7.1. The evolution of the cybernetic counterculture

4.7.2. Deus ex machina: a deadly phantasy?

5.1. Leary: a pioneer of cyberspace

5.2. Think for Yourself, Question Authority

21. Political Prisoners, Prisons, and Black Liberation

Anarchists Believe In Free Association

Anarchists Are Anti-Nationalist

Anarchists Are Anti-Authoritarian

Anarchists Are Anti-Capitalist

Anarchists Believe In International Labor Solidarity

There is no such thing as race

Is this really your position on the war?

About Anarcho-Putinists (Anatoliy Dubovik)

Myth 3: The Russian Empire can only be defeated by military force

Myth 23: Antimilitarism is important, but it is a problem when it becomes dogma.

Myth 29: In this war, democracy must win to prevent fascism/dictatorship from winning.

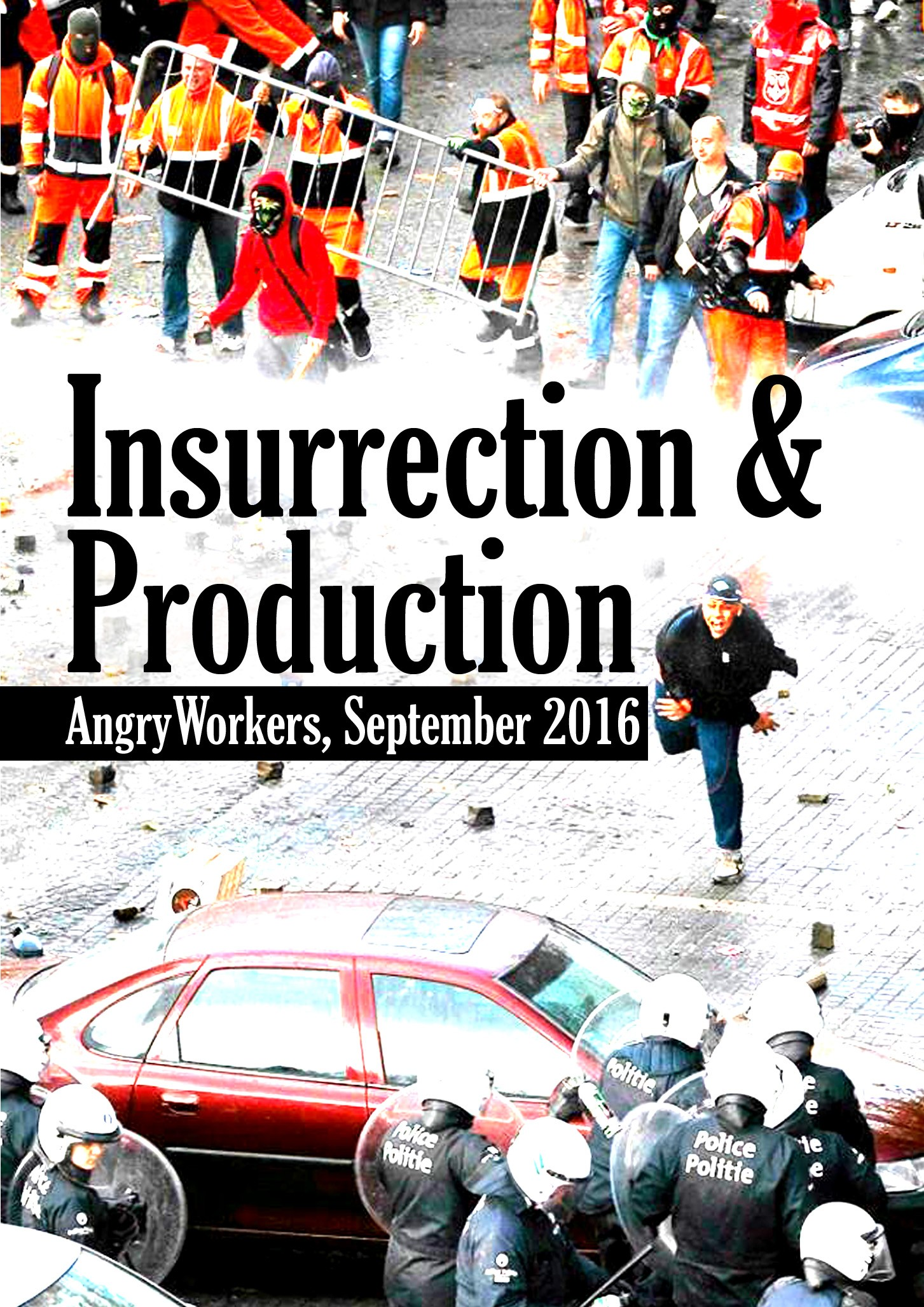

29. Insurrection and Production

a) The reality of struggle: a brief review of the 2010/11 uprisings from a revolutionary perspective

Total population in the UK region: 64 million

Size of companies in the UK (2015):

Food processing, production — 2.2 million people

Energy industry total: around 680,000 people

Transport total: 1.4 million people

Retail total — 2.7 million / Logistics total: 1.8 million / Warehouses total: 360,000

IT/Communication total: 1.2 million people

Care Sector: 3.2 to 3.5 million people

Construction: 1 to 2.1 million people

Engineering/Manufacturing total: around 3 million people

Public sector total: 5.1 million people

e) “Can anyone say ‘Communism?’”

What are the potentials and challenges for an insurrection within the UK territory?

30. A way propounded to make the poor in these and other nations happy

A way propounded to make the poor in these and other Nations happy, &c.

An invitation to the aforementioned Society or little Common-wealth, &c.

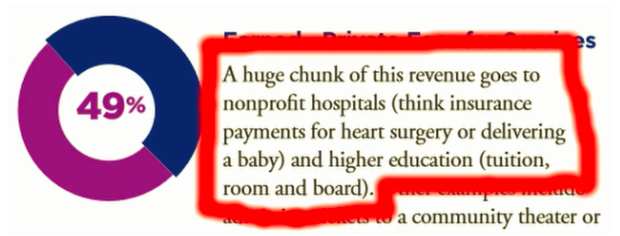

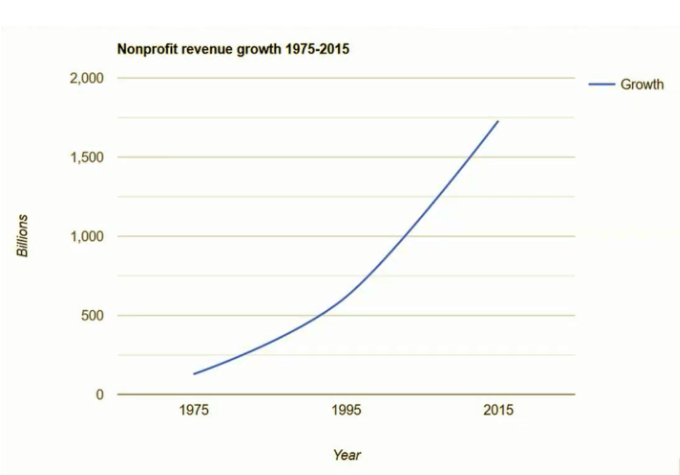

31. The Problem with Nonprofits

32. Imagination and the Carceral State

Education in the Era of the Crime Bill: What Questions Can We Ask?

The Myth-world in the Everyday Life of the Prison Classroom

The Limits of Sentimental Realism

33. A Half Revolution: Making Sense of EDSA ’86 and Its Failures

34. Pushed by the Violence of Our Desires

35. Black liberal, your time is up

36. Politics at the End of History

37. From Urumqi to Shanghai: Demands from Chinese and Hong Kong Socialists

Recognition of White Culture, What It Is, and How It Works

Section One — Definitions of Whiteness and White Culture

Section Two — Recognizing and Accepting

Section Three — Assimilation and Integration

The System and Disconnecting From It

Section One — Friends and Family

Section Four — Operational Security

Section Five — Mitigating the Risk of Violent Backlash

Section One — White Saviorship

Section Three — Planning and Organizing Actions

Section Four — Awareness, Disruption, Destruction, Altruism, and the Uniqueness of Street Protests

Section Five — Types of Violence

Section Six — Legally Resisting, a Useless Endeavor

Section One — Not Everybody Will Want You In the Fight

Section Two — Your Life Will Be Worse

Section Three — You Are Not Oppressed

Section Four — The Revolution Will Not be Won in a Day

39. A history of true civilisation is not one of monuments

40. Rethinking cities, from the ground up

41. Community Control, Workers’ Control, and the Cooperative Commonwealth

Race and the Revolutionary Subject

43. Basic Politics of Movement Security

G20 Repression and Infiltration in Toronto: an Interview with Mandy Hiscocks

45. The Shape of Things to Come

Part 1 (An Interview with J. Sakai, conducted from mid-2020)

Part 2 (Conclusion of an interview emailed back and forth into mid-2022)

Introduction from “Marginalized Notes / Monday Nov. 28, 2022”

Interdependent decision-making

Politeness and perspective taking

47. Exiting The Vampire Castle

A library enthusiasts introduction

This text was created for anyone curious about various library crew’s archiving ethoses.

The internet, bookshops, and libraries are all swamped with more information than anyone could read in a lifetime, but when searching for reading on a particular subject, having the choice of a 100 texts on that subject isn’t necessarily valuable if the task of choosing between them is made more difficult by a library crew’s choice to archive 50 texts that showcase embarrassingly anti-anarchist ideas, or where the one text that would interest you most has been deleted from the catalog due to the library crew having a personal issue with the author.

Therefore, when browsing texts from these institutions it would be valuable to get a sense of what type of texts are likely included at a higher or lower rate. So, what type of texts it is better to go elsewhere to look for. A simple brochure or web page people could read would suffice, to see a list of some of the texts that were controversially included or excluded, and ideally the reasons why.

Finally, I think there is value in discussing the embarrassment some people feel about controversially platforming some texts under the banner of ‘The Anarchist Library’. For example, if one of the reasons for hosting a text on the The Anarchist Library is that it can’t easily be found elsewhere, then having that be more well-known may encourage people to start a unique archival project specifically for exploring texts on that subject. Also, most every anarchist would agree that platforming the complete works of Mao under the banner of The Anarchist Library just because he was an ex-anarchist would be an unjustifiably embarrassing platforming of ideas. So, I just think it would be good for the library crew to post publicly the arguments and counter-arguments for why they think archiving various controversial authors and texts would or would not amount to this kind of embarrassing platforming.

The Why, The How & The Lessons Learned

I was bored so I decided to spreadsheet the web.archive.org list of URLs of The Anarchist Library and sort them against the live sitemap.

This meant that I could see the list of texts that were once public on the library, but that have now been deleted.

Here’s some of what I found out:

-

Most of the texts are saved to unlisted URLs so that they can be remembered by librarians and searched through in an ‘unpublished console’.

-

Often the reason given for deleting a text was just because it was discovered that the text had lots of OCR errors, so fell below quality standards. I found a few texts that I thought were worth the time fixing, so I fixed them, re-submitted them and one has already been re-published.

-

I agreed that some of the texts weren’t suited for the anarchist library, but I was glad to find them as I thought they were worthwhile archiving on other libraries.

-

I disagreed with some of the reasons for deleting texts given by librarians, but I found the reasons interesting nonetheless for understanding the library crew’s archiving ethos.

Finally I’ve been able to gather together a collection of essays to display here for people who are curious to read some of the texts that were deleted for unclear reasons or because the librarians thought they weren’t anarchist enough.

None of the texts below are ones that were deleted due to a request by the author, or DMCA, or bad formatting.

I won’t show the unlisted URL’s in case a spam bot brakes the texts or something. Also, if any authors of the texts below stumble on this collection and wish to see their text removed, you can feel free to edit the text yourself to delete your section, or leave a note in the proposed edits, or email ‘TheLibraryofUnconventionalLives at proton.me’ and I’m sure it’ll be deleted.

Further reading

A Short List of Some of the Deleted Texts

-

Armenia doesn’t need another political party — it needs a MOVEMENT!

-

A way propounded to make the poor in these and other nations happy

-

A Half Revolution: Making Sense of EDSA ’86 and Its Failures

-

From Urumqi to Shanghai: Demands from Chinese and Hong Kong Socialists

-

Community Control, Workers’ Control, and the Cooperative Commonwealth

1. Finbar Cafferkey: The life and death of an Irish fighter ‘who put his money where his mouth is’ in Ukraine

Subtitle: ‘He was quite pragmatic about it’: Family and comrades tell the story of how an Achill islander (45) wound up first in Syria and later in Ukraine

Author: Conor Gallagher and Daniel McLaughlin

Topics: 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Finbar Cafferkey, Ireland, anti-imperialism, eulogy, obituary

Date: July 15, 2023

Date Published on T@L: 2023-09-04

Source: Retrieved on 4th September 2023 from www.irishtimes.com

A librarians argument for deleting: not anarchist, only mentions they were helped by anarchists

A librarians argument against deleting: ...

A readers argument for deleting: The story is about someone who wasn’t an anarchist and who it only mentions was helped by anarchists.

A readers argument against deleting: The network of internationalist and anarchist support for the Ukranian people is an important and inspiring subject.

Colm Cafferkey was getting a bag of chips in Keel on Achill Island when he got the call saying his older brother Finbar was missing in action on the front lines in Ukraine.

Finbar and two other international volunteers were fighting with Ukrainian units in April to keep open a vital supply route to the city of Bakhmut, which was on verge of being overrun by the Russian invaders.

A sustained mortar strike hit the group, causing many casualties. Amid the chaos no one could be sure what happened to the 45-year-old Mayo man.

For the next week the Cafferkey family was worried but hopeful. Finbar had a reputation for disappearing for days or weeks at a time, only to pop up in another city or country.

Colm recalls them attending 1996 All-Ireland football final between Mayo and Meath and Finbar failing to show up at an arranged meeting spot.

“He rings us a few days later and he is in London. And then he rings a week later and he’s in Holland,” Colm recalls with a smile. “He could go three months without texting you.”

A week after he first heard his brother was missing, Colm got confirmation: Finbar was killed in the strike near Bakhmut, the devastated city in Donbas, eastern Ukraine, during Europe’s bloodiest battle since the second World War. He is the third Irish man known to have been killed in the fighting since the war started in February 2022. Continued fighting and the trading of territory between the sides meant recovering his remains was impossible.

Interviews with those who knew and fought alongside Cafferkey paint him as a brave, occasionally withdrawn man who was unable to stand still for long and who was willing to make sacrifices for his beliefs, even when it meant working alongside ideological opponents.

“He put his money where his mouth is,” says Colm. “He thought long and hard about how he could help in the world.”

Growing up as one of five children in an Irish-speaking family in Achill, Cafferkey was a voracious reader. He took an interest in Irish history and the Troubles which shaped much of his republican worldview.

“He was really stubborn but really fair as well,” says Colm, four years his junior. Colm remembers his older brother figuring out at the age of six that Santa wasn’t real.

“But he didn’t tell the rest of us,” he says.

As a teen, he was “never bound by social expectations,” says Colm. “I wouldn’t say it made a loner of him but it made him stand out.”

Cafferkey went to college for a while, spent a short period with the Army Reserve and worked various jobs, including in construction. By the mid-2000s, he was drifting somewhat, his brother recalls.

That’s when he became involved in Shell to Sea. This was the grassroots protest against the construction of a gas pipeline through north Mayo, which campaigners said would pose serious health and ecological risks.

Finbar had involved himself in some activist causes before but his participation in the Shell to Sea protests was transformative.

“That was a big moment for him. Once he got in there, he couldn’t step away,” says Colm. “It set him on a certain trajectory.”

In 2015 Finbar travelled to Greece to assist the huge numbers of Middle Eastern migrants arriving in rubber dinghies on the island of Kos. It was perhaps there where he conceived of the idea of trying to address the source of the refugee crisis directly.

He never told his family he was travelling to Syria in 2017, which was then six years into a bloody and complex civil war. He enlisted with a heavy weapons unit of the YPG, a left-wing Kurdish militia that was fighting to oust Islamic State from its base in Raqqa in the north of the country.

The first time Colm knew his brother was in Syria was when a video appeared online of him wearing a traditional Kurdish scarf and carrying a Kalashnikov.

“I came here because I admire the struggle of the Kurdish people,” says Finbar on the video, drawing parallels between the YPG and the IRA.

I knew there were two new guys coming who were hardcore republicans. I was a bit wary as I had served in Northern Ireland ... I really took to Fin straight away

— A former British soldier who met Finbar Cafferkey in Syria

Colm was shocked at the video “but really proud of him as well. It’s such a step for someone to take.”

When he later spoke to Finbar, he realised he had “thought long and hard” about the decision. “He had prepared himself mentally for it. No one had brainwashed him,” he says.

While undergoing military training in Syria, Finbar met Mark Ayres, a former British army soldier.

“I met Fin in northern Syria at the YPG training academy for international volunteers,” says Ayres. “I knew there were two new guys coming who were hard-core republicans. I was a bit wary as I had served in Northern Ireland and didn’t know how we would get on. I need not have worried as I got along with both of them ... I really took to Fin straight away.”

The YPG was successful in destroying Isis, also known as Islamic State, leaving Cafferkey searching for another cause.

At the time he was sort of idle and trying to think of what he would do next. He was quite pragmatic about it. He didn’t have children. He was in a position where he thought he could help

— Colm Cafferkey

When Russia invaded Ukraine last year, Colm knew immediately his brother was likely to get involved.

“At the time he was sort of idle and trying to think of what he would do next,” says Colm. “He was quite pragmatic about it. He didn’t have children. He was in a position where he thought he could help.”

Thousands of foreign fighters have travelled to Ukraine to aid in the fight against Russia, including dozens from Ireland. Some have extensive military experience; others have none.

“Some are basically kids who should never be there and are probably a danger to themselves and others around them,” says an Irish man who has fought in Ukraine who asked not to be named as he intends to return to the frontline soon.

“There’s others who tend to be older and have that bit of experience in fighting or medicine or logistics, and they can be helpful.”

Finbar Cafferkey seemed to fall in to the latter category.

“He said to me before that war is awful, that so many people are not able for it, that it ruins them,” says Colm. “He felt he was able to go to it and be around that stuff without it completely destroying him.”

Cafferkey made contact with an anarchist group in the Polish capital, Warsaw, and travelled from there to Ukraine to try to join a volunteer defence unit, preferably one made up of like-minded leftists.

But in those frantic first weeks of war, Ukraine’s forces struggled to equip all the volunteers who wanted to fight. Cafferkey returned to eastern Poland without signing up.

“I got a message that two comrades were coming and could we host them,” says a member of the Anarchist Black Cross Galicja group (ACK Galicja), who uses the pseudonym Leon Czołg.

“The other comrade was more orientated to fighting over there so he didn’t stay long. But Ciya stayed,” he adds, using the nom-de-guerre Finbar took in Syria.

Czołg first met Finbar and the other man, who is from Scandinavia, in ACK Galicja’s warehouse in eastern Poland, where he found them “tearing apart” bulky boxes of medical supplies and turning them into lightweight combat first-aid kits.

“They looked like serious, proper guys ... That’s what struck me from the beginning. They had only just arrived but they wanted to put their energy straight into the warehouse without messing around,” he says.

Cafferkey began making aid delivery runs to places deeper and deeper inside Ukraine, eventually to eastern Donbas, near the front line.

“He would come with a vehicle and say, ‘I have got a week or two and I will go wherever you tell me,’” says Sergey Movchan, an organiser in Kyiv for anti-authoritarian volunteer network Solidarity Collectives, which sends supplies to civilians and soldiers in Ukraine.

“Maybe he had some fear but he didn’t show any. He was very calm and kind and willing to help.”

On one run to Mykolaiv in southern Ukraine, which was then under daily shelling, Finbar reconnected with Mark Ayres.

“A few times I tried to talk him into joining my unit. He always declined and said he would carry on helping civilians ... I was shocked to learn that he joined up,” says Ayres.

Cafferkey is thought to have revived his initial aim of taking up arms when he heard about plans to form the kind of leftist unit he had sought at the start of the war.

Its commander was Dmitry Petrov, a leading light in the anarchist underground in Russia with a long record of opposition to the regime of Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Petrov had also spent time with Kurdish guerrillas in Syria and Iraq.

“It was a surprise for me that Ciya [Finbar Cafferkey] decided to join Leshiy’s unit,” says Sergey Movchan, of the anti-authoritarian volunteer network Solidarity Collectives, using one of Petrov’s many pseudonyms.

“Before he went to training, I asked Ciya whether maybe this was not the best time – there was very heavy fighting near Bakhmut, lots of people were being injured and dying, and my Facebook page was like one big obituary.”

Cafferkey and some anarchist comrades were so eager to join they agreed to train for a month under the Bratstvo (Brotherhood) battalion linked to a far-right Christian movement.

In March, Petrov and Cafferkey met in Kyiv with former US marine Cooper “Harris” Andrews and an activist from a Ukrainian environmental group who uses the pseudonym “Yenot” (Raccoon), before travelling to the Bratstvo training ground.

“We all decided that we can spend a few weeks with these guys because we have a bigger goal, and after this we can start something of our own,” says Yenot (26).

“It was actually better than expected. Every day there were things we didn’t like – their symbols and songs, for example – but in general it was all right ... There was no hostility. We were all in the same situation and wanted to train. We were on same side, fighting the same enemy.”

One trainer was “Madzh”, a Bratstvo fighter who says Finbar performed well with physical and weapons training. Around this time the Mayo man took a new nom-de-guerre, Osyp, a traditional Ukrainian name.

On April 17th the Bratstvo fighters and the four anarchists drove east through the night to a town near Bakhmut and the so-called road of life, which was the last open supply route for Ukrainian troops fighting a rearguard action in the ruined city.

Cafferkey, Petrov and Andrews were assigned to a combat platoon and Yenot to a medical unit that would treat the wounded.

“Before the fight they were optimistic, with a good fighting spirit. I clearly remember Harris repeating the phrase: ‘We come and they die.’ Ciya seemed calm, as always, and confident,” says Yenot.

“I said I wished we could have a beer together, and Leshiy replied: ‘Don’t worry, we will finish this mission and when we have won, we will have a beer.’”

Madzh remembers Finbar having a moment of doubt before the battle, as he says happens quite often in such situations.

Finbar said he had a bad feeling about the mission, prompting his commander to suggest he should stay behind. “But Finbar said, no, he wasn’t going to leave the group.”

The operation started on the morning of April 19th.

“An eyewitness, someone who was in combat there, told me it was a horrible scene. There were a lot of corpses from both sides in those trenches,” says Yenot.

“Someone on the radio said the guys were about 100m from the enemy, and it sounded like they would soon finish their job. I didn’t know that the real hell was about to begin.”

Footage from the road at this time shows shell-blasted fields criss-crossed by trenches where soldiers struggled through thick mud and clambered past crumpled bodies.

“It was near Bakhmut, so everything was firing: artillery, tanks, rifles, drones dropping grenades,” says Madzh.

“There were lot of explosions there, happening all the time. The land is full of craters from explosions. A Kalashnikov is like a children’s toy there.”

Yenot says Russian mortars landed to the right and left of her comrades before directly hitting their trench.

“One of the commanders said Ciya [Cafferkey] and Harris had been killed,” she says. Leshiy was later confirmed dead, too.

The grief felt by the men’s anarchist friends was compounded by Bratstvo’s claim that they had “joined” the far-right Christian movement with “strange leftist beliefs” but had subsequently “learned to respect faith and love God” and “took part in worship”.

In the Kyiv office where he last saw Cafferkey, Movchan recalls the Achill man telling him how training with Bratstvo had been “funny and weird and he had really thought about quitting”.

“But they decided, basically, to get through this and then they would have their own unit without all this religious bullshit,” adds Movchan.

Photographs of the three dead men stand in the Solidarity Collectives office, where in May dozens of people, including Petrov’s parents, gathered to honour them. Finbar’s family joined the event by video link.

“Many people would ask Ciya what he, an Irish person, was doing in Ukraine,” says Movchan. “And Ciya would reply that he had decided that he could be useful here, and he had time.”

When news of Finbar’s death was confirmed in Ireland, Tánaiste Micheál Martin paid tribute to him in the Dáil, calling him a “man of clear principles”. It was a relatively uncontroversial statement from the Government, which didn’t want to be seen to be encouraging people to travel to Ukraine to fight.

But it caught the ire of Russia’s ambassador to Dublin, Yuriy Filatov, whose embassy issued a statement blaming the media and the Irish Government for Finbar’s death in a Russian mortar strike.

“We also do not know if Mr Martin’s remarks signify support for the Irish to take part in combat in Ukraine, but we do know that if that is the case, then Ireland would be the direct participant of the conflict with all the ensuing consequences,” the embassy said.

The remarks drew a furious response leading to calls for Filatov’s expulsion. Colm Cafferkey, still coming to terms with his brother’s death, was not comfortable with the furore. He saw various sides, including supporters of Nato, trying to lay claim to his brother’s memory.

He issued his own statement. Finbar was, he said, against “all forms of imperialism, be it US, British, or Russian, and was strongly opposed to Ireland’s support of US troops and any moves towards joining Nato”.

The statement continued: “He was in Ukraine to help the Ukrainian people, as he would have helped any person in the world who was under attack.”

Looking back, Colm says he owed it to Finbar to clarify his position. “He wouldn’t have been any more in favour of Nato than he was the Russian gang.”

The Cafferkey family are still grieving as they await the return of Finbar’s remains, which are stored in a Ukrainian military base, alongside many others, awaiting formal identification.

It may be several more months before repatriation can occur and a funeral can be held.

“We’ll bring him home, le cúnamh Dé,” his father, Tom, said at a memorial service on Achill in May.

Does he hold any anger towards his brother for putting himself in such a dangerous situation? Colm pauses to think.

“That hasn’t hit me yet,” he says. “It feels like the really heavy emotions are still out in front of me still ... but it’s not anger. He knew what he was doing. He wouldn’t have had regrets.”

2. Thirty Years Ago Today I Shot My First Fascist

Author: Ali Al-Aswad

Topics: anti-fascism, anti-imperialism, history, Palestine, armed struggle

Date: 30.07.2008

Date Published on T@L: 2024-03-06

Source: <indymedia.org.uk/en/regions/leedsbradford/2008/07/405016.html>

A librarians argument for deleting: is this by an anarchist? doesn’t use the word, couldn’t find info about it online

A librarians argument against deleting: ...

A readers argument for deleting: ...

A readers argument against deleting: The author of this text is anonymous, but it was posted at the same time as an interview of a public anarchist PLO volunteer with a similar life story and lots of other anonymous texts exist on the website. Anarchist internationalists often write under local names given to them during their service. The text feels very relevant to the current bombing of Gaza and anarchist participation in protests against the bombings.

The camp was in a remote location in the Zahrani river valley. Access was by a steep track that snaked down the hillside from the Sida road. The track came to an end alongside what had been a farmhouse once, consisting of a stone hut where some of the men slept. Beneath this was a much larger stone manger, this was unused except by a few chickens, but in the warm weather it’s flat roof became the main focus of the camp, being used for both eating and sleeping. Beyond this building were a few tents, one of which was my home. Straight ahead was a blind valley which held a concealed ammunition dump and field guns, but before that was a large tent in which several older fedayi lived. Some were recovering from injuries sustained in the conflict.

To the left of the manger a path led down to another stone building which acted as a storeroom for tinned food, dried foodstuffs, and also ammunition. The storeroom was built into the hillside, having a flat roof, and adjacent to this was a large stone water-tank, which had been cut into the terrain. Below the tank and next to the storeroom was a water-tap, and further along the path was the Zahrani river itself.

The camp was isolated and quite vulnerable, with the Phalangist-held village of Haga visible high on the far hillside across the river. Nonetheless, throughout my life, I have rarely felt more safe.

Ostensibly the camp was under the command of Abu Abdullah, a thoughtful, introspective man aged somewhere in his 30’s. He had jet black hair and a full beard. The structure of the camp was entirely democratic though, and it had a militant reputation. Only weeks before our arrival the men had refused Yasser Arafat admission to the camp because they disagreed with a political decision he had taken.

Our training instructor was Ali Hassan from Gaza. He was aged only 23, but after 10 years fighting, it was impossible to guess that. He was tough, but with a warm, friendly manner, and bore a striking (and possibly cultivated) resemblance to Che Guevara. We also received some technical instruction from Jaffa, a Russian-trained armourer.

The older men kept to themselves for the most part, but I got on well with them, on occasion drinking tea and eating freshly caught fish in their large tent. Abu Muhamed was of the same age as the others, but he was still a very active fighter, and once saved my life.

Also at the camp was Abu Fathi, a round black man, filled with humour. Muhamed Ali had come to fight all the way from Sarajevo, a town in Yugoslavia I’d never heard of at the time. There were many more at the camp whose names I forget.

On the last day of July though, as darkness fell, the camp was nearly empty. Why I cannot recall, but there was only myself, Ali Hassan, and my English comrade (who had been given the nom de guerre Jihad), sat out on the roof of the manger. The older men were probably in their tent, but would have been out of earshot, while others I think were at the house at the top of the track, which guarded the Sida road.

We had just finished eating. There was little food because of the war, and we ate simply, sharing a plate in the traditional Arab manner. Suddenly Ali Hassan became alert, motioning for us to listen. I could hear nothing untoward, but Ali said he had heard something down towards the river. We both grabbed our Kalashnikovs and I strapped on my belt containing extra magazines of ammunition. As we stepped into the darkness and towards whatever was there, leaving Jihad to guard the house and wait for assistance, I felt no fear at all, except perhaps that I might be afraid.

Turning left in front of the manger, we skirted up the steep hill to the right, eventually passing the open water-tank and crawling on our stomachs across the flat roof of the storeroom. We reached the edge, with the level ground next to the river perhaps 30ft below us. We looked into the darkness listening for the slightest sound which might mean a raiding party of Israelis or Phalangists.

Ali beckoned me towards him and I rolled over. He pointed towards the dense undergrowth next to the narrow path which ran alongside the river. As I squinted in the darkness I saw the shape of a man standing, then another kneeling, and others behind. I could make out perhaps 4 or 5, but there were most likely others hidden in the darkness. The ones I could see were carrying Kalashnikovs, which meant they were almost certainly Phalangists rather than Israelis.

On my stomach I followed Ali back across the flat roof. Then he jumped into the darkness. I leapt after him, the fall seemed to last forever. It must have been at least 25 feet, but I landed well on the path below. As we slid the selector switches on our rifles onto full auto, Ali gestured for me to aim to the left and he would aim to the right.

We both came round the corner of the stone storeroom firing. I aimed into the darkness to the left of our position, firing on full auto and raking my gun round until it pointed straight ahead. Ali did the same, but starting from the right. We emptied our magazines. The fascist raiding party did not get the chance to return fire.

3. Unbreakable

Author: Ali Al-Asfa

Topics: Palestine, armed struggle

Source: <tiktok.com/@user2990229552439/photo/7301346753133956385>

A librarians argument for rejecting: not anarchist, no mention of anarchist word, unknown author

A librarians argument against rejecting: ...

A readers argument for rejecting: No mention of anarchist word and unknown author.

A readers argument against rejecting: Anarchist internationalists often write under local names given to them during their service. It feels very relevant to the current bombing of Gaza and anarchist participation in protests against the bombings. The author is anonymous, but it was posted at the same time as a public PLO volunteer with a similar life story and lots of other anonymous texts exist on the website.

The first time it happened, I was asleep, curled up with my ‘Kieshen’ beside me, and awoken by the sound of explosions, and the sonic boom of the jet, which had already passed overhead. Since I was, as always, fully clothed, and wearing my boots, it took only seconds to run outside. All I knew is that we were under attack. Other fighters were already outside, or running alongside me, but there were no enemy soldiers to confront. The war-plane, one of three, had flown out over the sea, and was already returning. We had no missiles, or heavy weapons, with which to confront it, and were told not to waste ammunition by firing. We found what little shelter we could, behind rocks.

The plane had arced round our small camp, dropping bombs on other positions, but when it returned, so low in the sky, nothing had prepared me for its vastness. It seemed like a huge spaceship, with the flashing lights on its belly, adding to the effect. It was so low, it felt like I could have reached out, and touched it, the seams and bolts on its skin were clearly visible, as was the face of the pilot within. The machine fired rockets, and spat cannon fire. The pilot saw me clearly, as I looked up, together with my comrades, but he was already flying past. As he went over, I could see two other planes, bombing the nearby town, where only women and children, and some old men, lived.

Thankfully we suffered no casualties that day, but it was not the same in the town, and in the afternoon, some small boys came to show us the large pieces of twisted metal they had found, parts of Israeli cluster-bombs. The bombing had taken place in support of the Lebanese Falange, the fascist militia, the Zionists perversely supported, and with whom we, and the Syrian Army at that time, were engaged in fighting.

Over the following weeks, and months, we were subject to regular air raids, almost always at first-light, but they could come at any time, as could shelling from the sea. There would be three planes, and they would make two or three bombing runs. We would check everyone was uninjured, go for our morning run, exercise under the strict instruction of our sergeant, Ali Hassan of Gaza, and then have breakfast. The air -raids became like a diabolical alarm-clock, with which we started our day.

The war-planes ruled the skies unopposed, except in Beirut, where there were heavier weapons, and the sight of an Israeli jet would be met by fire from hundreds of heavy ‘Deutchka’ machine-guns, mounted on Chevy trucks. The same was true of towns like Sida, which the Zionists bombed regularly. Fatah, at that time, possessed only one SAM-7 missile, and the order to fire it was not given.

Back at the camp, frustrated by the impunity of the enemy, we begged to confront them with the few heavier machine-guns, and more plentiful RPGs, we possessed. On one occasion, permission was granted, and we waited in the shallow valley, which the planes used as a path to our camp. Hiding behind huge boulders, we armed our weapons, and prayed for them to come, but on that day, they never did.

We were fighters, committed to the armed struggle against the Zionist entity, and their fascist proxy army. Despite our frustration at the inequality of our arms, and the fact the cowards rarely got out of their machines to fight us, we considered ourselves legitimate targets. We were not like the innocent people of Gaza, who have absolutely no way of either defending, or protecting, themselves, and on whom much bigger bombs, and in vastly greater numbers, have rained down relentlessly. I saw many terrible things in my years as a fighter, I witnessed many cruelties, and suffered many hardships, but they were as nothing compared to what the children of Gaza are subject to today.

However, I have absolutely no doubt that the courage of the Palestinian people will not fail them, that the viciousness of the Israeli genocide will not break them, and that one day the Colonialist Zionist state will be nothing more than a sickening footnote in history, which some will look back on in shame.

Free Palestine!

4. Child Molestation vs. Child Love (Critically Annotated)

Authors: Black Oak Clique & Wolfi Landstreicher

Topics: sex, criticism, egoism, critique

Date: 2019, 1987

Date Published on T@L: 2019-08-26

Source: https://heresydistro.noblogs.org/

A librarians argument for deleting: because the author didn’t want it up (the library presumed)

we don’t know. wolfi doesn’t use the internet

but we can presume that, because he left it out of every reprint of that collection, he didn’t want it out there

A librarians argument against deleting: ...

A readers argument for deleting: Likely the author’s preference.

A readers argument against deleting: Wolfi’s philosophy and creative writing style has been the subject of popular discussions among anarchists, so it would be valuable to see a critique of how Wolfi marshalled his particular political philosophy in defense of child sexual abuse. Also, so that people can feel better prepared to be able to notice and critique this kind of apologia for abuse if it’s ever taken up by other people in one’s own life.

Introduction: A Word of Warning

Here Be Dragons

The material contained in this text is gut-wrenching and disturbing. What follows is a critically annotated edition of Apio Ludd / Feral Faun / Wolfi Landstreicher’s Child Molestation vs. Child Love, from his (otherwise celebrated) anthology, Rants, Essays and Polemics. It is a defense of the sexual abuse of children and, ironically, a call to “fight the real child molesters” — Landstreicher’s term for parents, schools, and churches. In some parts of the work, it is quite graphic and the reader should tread lightly. Those who have suffered child sexual abuse in the past may want to stop here. It is presented with criticism. It is not in the interest of Heresy Distro to distribute molestation apologia by itself. Our choice of publishing this work is in the interest of knowledge — not of the arguments of self-styled “child lovers,” but rather knowledge about Wolfi Landstreicher’s views on “child love" so that one can act accordingly in their interactions with him.

Morals?

Our intent is not to moralize. Our motives for publishing Child Molestation is love — real, egoistic love for children. We do not believe it is our “duty” to protect children nor are we guided by any outside, abstract, spectral “morals” to do so. It is rather our lived, experienced, and felt camaraderie with children; with our desire to return to the pre-civilized and Wild existence that is childhood. Rarely is there a moment with children when they are not mesmerized by the natural world — insects, spiders, the grass, squirrels, rocks, rain, thunder. This is not merely naïve curiosity. Children exist in a state before the bifurcation into man and animal. Truly, the trope of the “feral child” is not a child who has lost their humanity. Rather, they never developed it.

Childhood “sexuality”

One cannot deny that children possess a sort of sexuality, or, more precisely, what adults term sexuality. Childhood is a stage of exploration, and it is to be expected that children will partake in bodily exploration as well — individual and collective.

However, it must be made abundantly clear that a child’s conception of sexuality is much different than an adult’s. Children do not possess a concept of, and thus cannot grant, consent. Thus, an adult (who possesses a grasp on consent) who engages a child sexually will be enacting a sort of sexualized authority over them. Further, children are scarcely aware of the power dynamics that mark adult sexuality, and therefore cannot contend with and rectify them, as adults can. They are made into objects of pleasure, not, as Landstreicher contends, equal partners in a mutually-beneficial erotic relationship.

When one’s reading of Child Molestation vs. Child Love is informed by this understanding, the true content of the piece is laid bare: a quasi-egoist appropriation of anarchist rhetoric to justify (and perhaps hide) a cruel and authoritarian desire to control and fetishize the bodies of children.

Child Molestation vs. Child Love (Main text from 1987)

A child is scolded, restricted, forced to conform to schedules and social norms, limited, bribed with rewards and threatened with punishments. This is called love. A child is kissed, caressed, played with, gently fondled and given erotic pleasure. This is called molestation. Something is obviously twisted here. (1)

One of the main dichotomies of this society is the child/adult dichotomy. It has no basis in any real needs or natural ways. It is a totally arbitrary conception which only serves to reinforce authority. (2)

Certainly, newborn infants need to be fed and watched over until they can begin to move around their environment with some ease, steadiness, and self-assurance. And thereafter, it is certainly a kindness to inform them of anything they may need to know to avoid accidents and relate well to their environment. But the structuring and regimentation a child undergoes in our society has nothing to do with natural needs or kindness. It is the slow destruction of the child’s freedom under authority. (3)

From the moment an infant is bone s/he is in the firm hand of authority. S/he is almost immediately forced to feed on a schedule. Early on, s/he begins to see that the “love” of most adults is something that must be bought by conformity and obedience. Sensuality begins to be repressed by the scheduling of feeding and the use of diapers and other clothing even when they’re uncomfortable. Toilet training continues the process. And the constant threat of punishment instills the fear necessary to keep the process of sensual repression going strong. All of this is the dirty work of parents. What defines a “good” parent is their ability to instill this repression appearing to be the monsters they are. For once this repression is well begun, the child can be easily molded into what this society wants. School completes the process begun by the parent. It forces the child to regiment most of her/his daylight hours. Sensual activity is straight-jacketed during this time. After school, there is homework which the parents make sure the child does. This process usually continues well past puberty. All of these years of repression and forced acquiescence to authority make the child into a grown-up (more accurately, a groan-up), which, in this society, means a conforming, obedient, and usually anxiety-ridden slave.

It is the nature of this education process which makes society define the child-lover as a devil. For to the child-lover, a child is not a lump of clay to be molded to the will of authority. S/he is a god, the manifestation of Eros. The child-lover encourages the free expression of the child’s sensuality and so undermines the entire education process. And the child, who has not yet been as repressed as her/his adult lover, helps to break down the repression within the adult. How could a society which requires repressed, conforming, obedient groan-ups possible tolerate child love? (4)

It is clear who the true child molesters are. The parents and schools rape the minds of children, forcing guilt and fear, conformity and obedience to authority upon them, repressing their sensuality and imagination, their wild erotic ecstasy. (5) But children are still less repressed than most adults. Their divinity still shines through with an especially clear beauty. For they are not mere clay to be molded. They are wild, dancing gods. To adventure erotically with children is liberating both for the children and for we “adults” who are really just repressed children. It is a major blow against authority and an expression of paradise. For we all are gods, and all shared pleasure is a beautiful expression of our divinity. So let us fight the real child molesters, the family, the school, the church, and all authority, and share erotic pleasure as freely as we can with children. Then we may again regain our own repressed childhood and become the gods we truly are in beauty and in ecstasy. (6)

Critical Annotations by Black Oak Clique

1. As outlined in the previous section, child sexual abuse is not simply kissing, caressing, and playing with a child. This is a gross and intentional mischaracterization of child molestation. Further, one can be opposed both to the imposition of authoritarian social norms and the sexualization of children.

2. It is true in some sense that the child-adult dialectic serves to reinforce unequal power dynamics. We dispute, however, that the dichotomy has no basis in real needs or natural ways. Perhaps the only meaningful distinction between children and adults is the development of a concept of consent. However, Landstreicher himself even goes further than this — he contradicts himself in the very next paragraph. One must wonder what his intent here in “disrupting” this dichotomy is...

3. Here is the contradiction — newborn infants cannot feed or protect themselves sufficiently and are totally reliant on their parents. Again, it is true in some sense that the structuring of a child’s life is more for the good of capital-S Society than for the child themself. But to state that the child-adult dialectic is completely or wholly a construction of authority is fallacy. What is needed is not the complete or total destruction of the parent-child opposition. Rather, it is a radical reconstruction (or perhaps even a rediscovery) of the lived relationship of family. Unlike the empty, cold, mediated relationships we experience under industrial capitalism, the bonds of family, while certainly not wholly good in any sense, are fiery, hot, and emotionally potent. What is needed is not a destruction of the family — but liberation of it! Liberation from the chains of Morality and Obligation, and a reformation of the family as a real, lived experience.

4. In fact, the exact opposite is true. A child is exactly that to the “child lover” — an object to be molded according to authority. Landstreicher’s description of child molestation conveniently makes the truth of it opaque. Landstreicher’s child lover is more properly a child groomer, who, through the performance of affection and play, makes a child open to sexual acts they do not, and perhaps cannot, understand. They are not being “encouraged" to express their “sensuality." Their sensuality is being produced, they are turned into a machine for the production of sexual pleasure.

5. How convenient that the authorities Landstreicher charges with “true" child molestation are the ones who are most directly engaged in the protection of children from sexual predators!

6. Finally, Landstreicher closes with the clearest objectification of children in this “rant." For Landstreicher, in the end, the child is a tool for the production of an imaginary, repressed childhood. For Landstreicher, “child love" — molestation — is a ritual with which he can become feral and return to an Adamic state of “beauty and ecstasy.” It is not the relationship he intends to portray.

5. The Left-Overs

Subtitle: How Fascists Court the Post-Left

Author: Alexander Reid Ross

Topics: anti-fascism; fascism; fascist creep; post-left; criticism and critique; anarcho-primitivism; Bob Black; ELF; green anarchism; Hakim Bey; John Zerzan; Lawrence Jarach; Max Stirner; nihilism

Date: 29 March, 2017

Date Published on T@L: 2022-09-28T21:04:33

Source: Retrieved on 28 September, 2022 from antifascistnews.net

Notes: Alexander Reid Ross is a former co-editor of the Earth First! Journal and the author of Against the Fascist Creep. He teaches in the Geography Department at Portland State University and can be reached at <aross@pdx.edu>.

A librarians argument for deleting: not anarchist

A librarians argument against deleting: ...

A readers argument for deleting: ...

A readers argument against deleting: I think this is a cool critique of a small post-left to fascist pipeline.

Author’s Note: A few months ago, the radical publication, Fifth Estate, solicited an article from me discussing the rise of fascism in recent years. Following their decision to withdraw the piece, I accepted the invitation of Anti-Fascist News to publish an expanded version here, with some changes, at the urging of friends and fellow writers.

Chapter 1: The Early Composition of Fascist Individualism

A friendly editor recently told me via email, “if anti-capitalism and pro individual liberty [sic] are clearly stated in the books or articles, they won’t be used by those on the right.” If this were true, fascism simply would vanish from the earth. Fascism comes from a mixture of left and right-wing positions, and some on the left pursue aspects of collectivism, syndicalism, ecology, and authoritarianism that intersect with fascist enterprises. Partially in response to the tendencies of left authoritarianism, a distinct antifascist movement emerged in the 1970s to create what has became known as “post-left” thought. Yet in imagining that anti-capitalism and “individual liberty” maintain ideological purity, radicals such as my own dear editor tend to ignore critical convergences with and vulnerabilities to fascist ideology.

The post-left developed largely out of a tendency to favor individual freedom autonomous from political ideology of left and right while retaining some elements of leftism. Although it is a rich milieu with many contrasting positions, post-leftists often trace their roots to individualist Max Stirner, whose belief in the supremacy of the European individual over and against nation, class, and creed was heavily influenced by philosopher G.W.F. Hegel. After Stirner’s death in 1856, the popularity of collectivism and neo-Kantianism obscured his individualist philosophy until Friedrich Nietzsche raised its profile again during the later part of the century. Influenced by Stirner, Nietzsche argued for the overcoming of socialism and the “modern world” by the iconoclastic, aristocratic philosopher known as the “Superman” or “übermensch.”

During the late-19th Century, Stirnerists conflated the “Superman” with the assumed responsibility of women to bear a superior European race—a “New Man” to produce, and be produced by, a “New Age.” Similarly, right-wing aristocrats who loathed the notions of liberty and equality turned to Nietzsche and Stirner to support their sense of elitism and hatred of left-wing populism and mass-based civilization. Some anarchists and individualists influenced by Stirner and Nietzsche looked to right-wing figures like Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky, who developed the idea of a “conservative revolution” that would upend the spiritual crises of the modern world and the age of the masses. In the words of anarchist, Victor Serge, “Dostoevsky: the best and the worst, inseparable. He really looks for the truth and fears to find it; he often finds it all the same and then he is terrified… a poor great man…”

History’s “great man” or “New Man” was neither left nor right; he strove to destroy the modern world and replace it with his own ever-improving image—but what form would that image take? In Italy, reactionaries associated with the Futurist movement and various romantic nationalist strains expressed affinity with the individualist current identified with Nietzsche and Stirner. Anticipating tremendous catastrophes that would bring the modern world to its knees and install the New Age of the New Man, the Futurists sought to fuse the “destructive gesture of the anarchists” with the bombast of empire.

A hugely popular figure among these tendencies of individualism and “conservative revolution,” the Italian aesthete Gabrielle D’Annunzio summoned 2,600 soldiers in a daring 1919 attack on the port city of Fiume to reclaim it for Italy after World War I. During their exploit, the occupying force hoisted the black flag emblazoned by skull and crossbones and sang songs of national unity. Italy disavowed the imperial occupation, leaving the City-State in the hands of its romantic nationalist leadership. A constitution, drawn up by national syndicalist, Alceste De Ambris, provided the basis for national solidarity around a corporative economy mediated through collaborating syndicates. D’Annunzio was prophetic and eschatological, presenting poetry during convocations from the balcony. He was masculine. He was Imperial and majestic, yet radical and rooted in fraternal affection. He called forth sacrifice and love of the nation.

When he returned to Italy after the military uprooted his enclave in Fiume, ultranationalists, Futurists, artists, and intellectuals greeted D’Annunzio as a leader of the growing Fascist movement. The aesthetic ceremonies and radical violence contributed to a sacralization of politics invoked by the spirit of Fascism. Though Mussolini likely saw himself as a competitor to D’Annunzio for the role of supreme leader, he could not deny the style and mood, the high aesthetic appeal that reached so many through the Fiume misadventure. Fascism, Mussolini insisted, was an anti-party, a movement. The Fascist Blackshirts, or squadristi, adopted D’Annunzio’s flare, the black uniforms, the skull and crossbones, the dagger at the hip, the “devil may care” attitude expressed by the anthem, “Me ne frego” or “I don’t give a damn.” Some of those who participated in the Fiume exploit abandoned D’Annunzio as he joined the Fascist movement, drifting to the Arditi del Popolo to fight the Fascist menace. Others would join the ranks of the Blackshirts.

Originally a man of the left, Mussolini had no difficulty joining the symbolism of revolution with ultranationalist rebirth. “Down with the state in all its species and incarnations,” he declared in a 1920 speech. “The state of yesterday, of today, of tomorrow. The bourgeois state and the socialist. For those of us, the doomed (morituri) of individualism, through the darkness of the present and the gloom of tomorrow, all that remains is the by-now-absurd, but ever consoling, religion of anarchy!” In another statement, he asked, “why should Stirner not have a comeback?”

Mussolini’s concept of anarchism was critical, because he saw anarchism as prefiguring fascism. “If anarchist authors have discovered the importance of the mythical from an opposition to authority and unity,” declared Nazi jurist, Carl Schmitt, drawing on Mussolini’s concept of myth, “then they have also cooperated in establishing the foundation of another authority, however unwillingly, an authority based on the new feeling for order, discipline, and hierarchy.” The dialectics of fascism here are two-fold: only the anarchist destruction of the modern world in every milieu would open the potential for Fascism, but the mythic stateless society of anarchism, for Mussolini, could only emerge, paradoxically, from a self-disciplining state of total order.

Antifascist anarchist individualists and nihilists like Renzo Novatore represented for Mussolini a kind of “passive nihilism,” which Nietzsche understood as the decadence and weakness of modernity. The veterans that would fight for Mussolini rejected the suppression of individualism under the Bolsheviks and favored “an anti-party of fighters,” according to historian Emilio Gentile. Fascism would exploit the rampant misogyny of men like Novatore while turning the “passive nihilism” of their vision of total collapse toward “active nihilism” through a rebirth of the New Age at the hands of the New Man.

The “drift” toward fascism that took place throughout Europe during the 1920s and 1930s was not restricted to the collectivist left of former Communists, Syndicalists, and Socialists; it also included the more ambiguous politics of the European avant-garde and intellectual elites. In France, literary figures like Georges Bataille and Antonin Artaud began experimenting with fascist aesthetics of cruelty, irrationalism, and elitism. In 1934, Bataille declared his hope to usher in “room for great fascist societies,” which he believed inhabited the world of “higher forms” and “makes an appeal to sentiments traditionally defined as exalted and noble.” Bataille’s admiration for Stirner did not prevent him from developing what he described decades later as a “paradoxical fascist tendency.” Other libertarian celebrities like Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Maurice Blanchot also embraced fascist themes—particularly virulent anti-Semitism.

Like Blanchot, the Nazi-supporting Expressionist poet Gottfried Benn called on an anti-humanist language of suffering and nihilism that looked inward, finding only animal impulses and irrational drives. Existentialist philosopher and Nazi Party member, Martin Heidegger, played on Nietzschean themes of nihilism and aesthetics in his phenomenology, placing angst at the core of modern life and seeking existential release through a destructive process that he saw as implicit in the production of an authentic work of art. Literary figure Ernst Jünger, who cheered on Hitler’s rise, summoned the force of “active nihilism,” seeking the collapse of the civilization through a “magic zero” that would bring about a New Age of ultra-individualist actors that he later called “Anarchs.” The influence of Stirner was as present in Jünger as it was in Mussolini’s early fascist years, and carried over to other members of the fascist movement like Carl Schmitt and Julius Evola.

Evola was perhaps the most important of those seeking the collapse of civilization and the New Age’s spiritual awakening of the “universal individual,” sacrificial dedication, and male supremacy. A dedicated fascist and individualist, Evola devoted himself to the purity of sacred violence, racism, anti-Semitism, and the occult. Asserting a doctrine of the “political soldier,” Evola regarded violence as necessary in establishing a kind of natural hierarchy that promoted the supreme individual over the multitudes. Occult practice distilled into an overall aristocracy of the spirit, Evola believed, which could only find expression through sacrifice and a Samurai-like code of honor. Evola shared these ideals of conquest, elitism, sacrificial pleasure with the SS, who invited the Italian esotericist to Vienna to indulge his thirst for knowledge. Following World War II, Evola’s spiritual fascism found parallels in the writings of Savitri Devi, a French esotericist of Greek descent who developed an anti-humanist practice of Nazi nature worship not unlike today’s Deep Ecology. In her rejection of human rights, Devi insisted that the world manifests a totality of interlocking life forces, none of which enjoys a particular moral prerogative over the other.

Chapter 2: The Creation of the Post-Left

It has been shown by now that fascism, in its inter-war period, attracted numerous anti-capitalists and individualists, largely through elitism, the aestheticization of politics, and the nihilist’s desire for the destruction of the modern world. After the fall of the Reich, fascists attempted to rekindle the embers of their movement by intriguing within both the state and social movements. It became popular among fascists to reject Hitler to some degree and call for a return to the original “national syndicalist” ideas mixed with the elitism of the “New Man” and the destruction of civilization. Fascists demanded “national liberation” for European ethnicities against NATO and multicultural liberalism, while the occultism of Evola and Devi began to fuse with Satanism to form new fascist hybrids. With ecology and anti-authoritarianism, such sacralization of political opposition through the occult would prove among the most intriguing conduits for fascist insinuation into subcultures after the war.

In the ’60s, left-communist groups like Socialisme ou Barbarie, Pouvoir ouvrier, and the Situationists gathered at places like bookstore-cum-publishing house, La Vielle Taupe (The Old Mole), critiquing everyday life in industrial civilization through art and transformative practices. According to Gilles Dauvé, one of the participants in this movement, “the small milieu round the bookshop La Vieille Taupe” developed the idea of “communisation,” or the revolutionary transformation of all social relations. This new movement of “ultra-leftists” helped inspire the aesthetics of a young, intellectual rebellion that culminated in a large uprising of students and workers in Paris during May 1968.

The strong anti-authoritarian current of the ultra-left and the broader uprising of May ’68 contributed to similar movements elsewhere in Europe, like the Italian Autonomia movement, which spread from a wildcat strike against the car manufacturer, Fiat, to generalized upheaval involving rent strikes, building occupations, and mass street demonstrations. While most of Autonomia remained left-wing, its participants were intensely critical of the established left, and autonomists often objected to the ham-fisted strategy of urban guerrillas. In 1977, individualist anarchist, Alfredo Bonanno, penned the text, “Armed Joy,” exhorting Italian leftists to drop patriarchal pretensions to guerrilla warfare and join popular insurrectionary struggle. The conversion of Marxist theorist, Jacques Camatte, to the pessimistic rejection of leftism and embrace of simpler life tied to nature furthered contradictions within the Italian left.

With anti-authoritarianism, ecologically-oriented critiques of civilization emerged out of the 1960s and 1970s as significant strains of a new identity that rejected both left and right. Adapting to these currents of popular social movements and exploiting blurred ideological lines between left and right, fascist ideologues developed the framework of “ethno-pluralism.” Couching their rhetoric in “the right to difference” (ethnic separatism), fascists masked themselves with labels like the “European New Right,” “national revolutionaries,” and “revolutionary traditionalists.” The “European New Right” took the rejection of the modern world advocated by the ultra-left as a proclamation of the indigeneity of Europeans and their pagan roots in the land. Fascists further produced spiritual ideas derived from a sense of rootedness in one’s native land, evoking the old “blood and soil” ecology of the German völkische movement and Nazi Party.

In Italy, this movement produced the “Hobbit Camp,” an eco-festival organized by European New Right figure Marco Tarchi and marketed to disillusioned youth via Situationist-style posters and flyers. When Italian “national revolutionary,” Roberto Fiore, fled charges of participating in a massive bombing of a train station in Bologna, he found shelter in the London apartment of Tarchi’s European New Right colleague, Michael Walker. This new location would prove transformative, as Fiore, Walker, and a group of fascist militants created a political faction called the Official National Front in 1980. This group would help promote and would benefit from a more avant-garde fascist aesthetic, bringing forward neo-folk, noise, and other experimental music genres.

While fascists entered the green movement and exploited openings in left anti-authoritarian thought, Situationism began to transform. In the early 1970s, post-Situationism emerged through US collectives that combined Stirnerist egoism with collectivist thought. In 1974, the For Ourselves group published The Right to Be Greedy, inveighing against altruism while linking egoist greed to the synthesis of social identity and welfare—in short, to surplus. The text was reprinted in 1983 by libertarian group, Loompanics Unlimited, with a preface from a little-known writer named Bob Black.

While post-Situationism turned toward individualism, a number of European ultra-leftists moved toward the right. In Paris, La Vieille Taupe went from controversial views rejecting the necessity of specialized antifascism to presenting the Holocaust as a lie necessary to maintain the capitalist order. In 1980, La Vielle Taupe published the notorious Mémoire en Défense centre ceux qui m’accusent de falsifier l’histoire by Holocaust denier, Robert Faurisson. Though La Vielle Taupe and founder, Pierre Guillaume, received international condemnation, they gained a controversial defense from left-wing professor, Noam Chomsky. Even if they have for the most part denounced Guillaume and his entourage, the ultra-leftist rejection of specialized antifascism has remained somewhat popular—particularly as expounded by Dauvé, who insisted in the early 1980s that “fascism as a specific movement has disappeared.”

The idea that fascism had become a historical artifact only helped the creep of fascism to persist undetected, while Faurisson and Guillaume became celebrities on the far-right. As the twist toward Holocaust denial would suggest, ultra-left theory was not immune from translation into ethnic terms—a reality that formed the basis of the work of Official National Front officer, Troy Southgate. Though influenced by the Situationists, along with a scramble of other left and right-wing figures, Southgate focused particularly on the ecological strain of radical politics associated with the punk-oriented journal, Green Anarchist, which called for a return to “primitive” livelihoods and the destruction of modern civilization. In 1991, the editors of Green Anarchist pushed out their co-editor, Richard Hunt, for his patriotic militarism, and Hunt’s new publication, Green Alternative, soon became associated with Southgate. Two years later, Southgate would join allied fascists like Jean-François Thiriart and Christian Bouchet to create the Liaison Committee for Revolutionary Nationalism.

In the US, the “anarcho-primitivist” or “Green Anarchist” tendency had been taken up by former ultra-leftist, John Zerzan. Identifying civilization as an enemy of the earth, Zerzan called for a return to sustainable livelihoods that rejected modernity. Zerzan rejected racism but relied in no small part on the thought of Martin Heidegger, seeking a return authentic relations between humans and the world unmediated by symbolic thought. This desired return, some have pointed out, would require a collapse of civilization so profound that millions, if not billions, would likely perish. Zerzan, himself, seems somewhat ambiguous with regards to the potential death toll, regardless of his support for the unibomber, Ted Kaczynsky.

Joining with Zerzan to confront authoritarianism and return to a more tribal, hunter-gatherer social organization, an occultist named Hakim Bey developed the idea of the “Temporary Autonomous Zone” (TAZ). For Bey, a TAZ would actualize a liberated and erotic space of orgiastic, revolutionary poesis. Yet within his 1991 text, Temporary Autonomous Zone, Bey included extensive praise for D’Annunzio’s proto-fascist occupation of Fiume, revealing the disturbing historical trends of attempts to transcend right and left.

Along with Zerzan and Bey, Bob Black would prove instrumental to the foundation of what is today called the “post-left.” In his 1997 text, Anarchy After Leftism, Black responded to left-wing anarchist Murray Bookchin, who accused individualists of “lifestyle anarchism.” Drawing from Zerzan’s critique of civilization as well as from Stirner and Nietzsche, Black presented his rejection of work as a nostrum for authoritarian left tendencies that he identified with Bookchin (apparently Jew-baiting Bookchin in the process).[1]

Thus, the post-left began to assemble through the writings of ultra-leftists, green anarchists, spiritualists, and egoists published in zines, books, and journals like Anarchy: Journal of Desire Armed and Fifth Estate. Although these thinkers and publications differ in many ways, key tenets of the post-left included an eschatological anticipation of the collapse of civilization accompanied by a synthesis of individualism and collectivism that rejected left, right, and center in favor of a deep connection with the earth and more organic, tribal communities as opposed to humanism, the Enlightenment tradition, and democracy. That post-left texts included copious references to Stirner, Nietzsche, Jünger, Heidegger, Artaud, and Bataille suggests that they form a syncretic intellectual tendency that unites left and right, individualism and “conservative revolution.” As we will see, this situation has provided ample space for the fascist creep.

Chapter 3: The Fascist Creep

During the 1990s, the “national revolutionary” network of Southgate, Thiriart, and Bouchet, later renamed the European Liberation Front, linked up with the American Front, a San Francisco skinhead group exploring connections between counterculture and the avant-garde. Like prior efforts to develop a Satanic Nazism, American Front leader Bob Heick supported a mix of Satanism, occultism, and paganism, making friends with fascist musician Boyd Rice. A noise musician and avant-gardist, Rice developed a “fascist think tank” called the Abraxas Foundation, which echoed the fusion of the cult ideas of Charles Manson, fascism, and Satanism brought together by 1970s fascist militant James Mason. Rice’s protégé and fellow Abraxas member, Michael Moynihan, joined the radical publishing company, Feral House, which publishes texts along the lines of Abraxas, covering a range of themes from Charles Manson Scandinavian black metal, and militant Islam to books by Evola, James Mason, Bob Black, and John Zerzan.

In similar efforts, Southgate’s French ally, Christian Bouchet, generated distribution networks and magazines dedicated to supporting a miniature industry growing around neo-folk and the new, ”anarchic” Scandinavian black metal scene. Further, national anarchists attempted to set up and/or infiltrate e-groups devoted to green anarchism. As Southgate and Bouchet’s network spread to Russia, notorious Russian fascist, Alexander Dugin, emerged as another leading ideologue who admired Zerzan’s work.

Post-leftists were somewhat knowledgable about these developments. In a 1999 post-script to one of Bob Black’s works, co-editor of Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed, Lawrence Jarach, cautioned against the rise of “national anarchism.” In 2005, Zerzan’s journal, Green Anarchy, published a longer critique of Southgate’s “national anarchism.” These warnings were significant, considering that they came in the context of active direct action movements and groups like the Earth Liberation Front (ELF), a green anarchist group dedicated to large-scale acts of sabotage and property destruction with the intention of bringing about the ultimate collapse of industrial civilization.

As their ELF group executed arsons during the late-1990s and early-2000s, a former ELF member told me that two comrades, Nathan “Exile” Block and Joyanna “Sadie” Zacher, shared an unusual love of Scandinavian black metal, made disturbing references to Charles Manson, and promoted an elitist, anti-left mentality. While their obscure references evoked Abraxas, Feral House, and Bouchet’s distribution networks, their politics could not be recognized within the milieu of fascism at the time. However, their general ideas became clearer, the former ELF member told me, when antifascist researchers later discovered that a Tumblr account run by Block contained numerous occult fascist references, including national anarchist symbology, swastikas, and quotes from Evola and Jünger. These were only two members of a larger group, but their presence serves as food for thought regarding important radical cross-over points and how to approach them.

To wit, the decisions of John Zerzan and Bob Black to publish books with Feral House, seem peculiar—especially in light of the fact that two of the four books Zerzan has published there came out in 2005, the same year as Green Anarchy’s noteworthy warning against national anarchism. It would appear that, although in some cases prescient about the subcultural cross-overs between fascism and the post-left, post-leftists have, on a number of occasions, engaged in collaborative relationships.